There are times when, facing the media, Jurgen Klopp feigns ignorance. It can be an unwanted question or, on the other hand, a question he welcomes but wishes to give the impression it had never crossed his mind.

But he was genuinely taken aback recently when, having sent shockwaves through the sport with his announcement that he will leave Liverpool at the end of the season, it was mentioned to him that Sir Alex Ferguson once called notice on his time at Manchester United — only to change his mind and stay on for… just another 11 years, as it happened.

“Alex Ferguson stepped down twice?” the Liverpool manager asked, as intrigued as he was bewildered. Even after getting an explanation, he came back to it. “Alex Ferguson? I didn’t know that…”

There is no reason why he should have. Klopp was still getting to grips with his first coaching role, at Mainz in the second tier of the Bundesliga, when Ferguson announced he would step down and retire from management at the end of the 2001-02 season.

Klopp told Liverpool in November he will leave this summer (Richard Sellers/Sportsphoto/Allstar via Getty Images)

As Ferguson put it, it was a “textbook case” of how to “botch” leaving a job — which is perhaps why he did it so differently when he stepped down for real in 2013.

It has become rare at the top level for a manager’s departure to be flagged months in advance. But lately, we have had a flurry of leaving statements: not just Klopp at Liverpool but Xavi Hernandez announcing he will leave Barcelona at the end of the season and Emma Hayes hoping to secure a seventh Women’s Super League title before she departs Chelsea for the United States national team job.

Klopp says he went public because, with the club needing to intensify their search for his successor, it would have been impossible to keep it secret. By contrast, Xavi says he went public because, after some chastening results in weeks, “Barcelona need a reaction and I think this is the best decision I could have made”.

But is it? The conventional wisdom in football is that the long goodbye rarely works out as gloriously as Klopp, Xavi and Hayes are hoping.

It is why, when it came to his eventual retirement in 2013, Ferguson did it very differently. He told chief executive David Gill and then the Glazer family in February. But not until May 8, with the Premier League title secured and just two games left, did he and the club announce it publicly, allowing him a glorious send-off from Old Trafford four days later.

It is telling that Ferguson describes the 2002 experience as his “biggest regret” in management.

“When the team thought I would be leaving, they slackened off,” he wrote in his 2013 autobiography. “A constant tactic of mine was always to have my players on the edge, to keep them thinking it was always a matter of life and death. The must-win approach. I took my eye off the ball, thinking too far ahead and wondering who would replace me. It’s human nature in those circumstances to relax a bit and to say, ‘I’m not going to be here’.”

All the talk at the start of that 2001-02 season was about Ferguson’s mission to win a second Champions League title, with the final to be held in his native Glasgow. He admits he became “obsessed” by the thought — but came to resent the media focus on his odyssey as his team started the season poorly, beaten six times in the Premier League by early December, which was unheard of in that era of Manchester United dominance.

“I cursed myself: ‘I’ve been stupid. Why did I even mention it?’” he wrote.

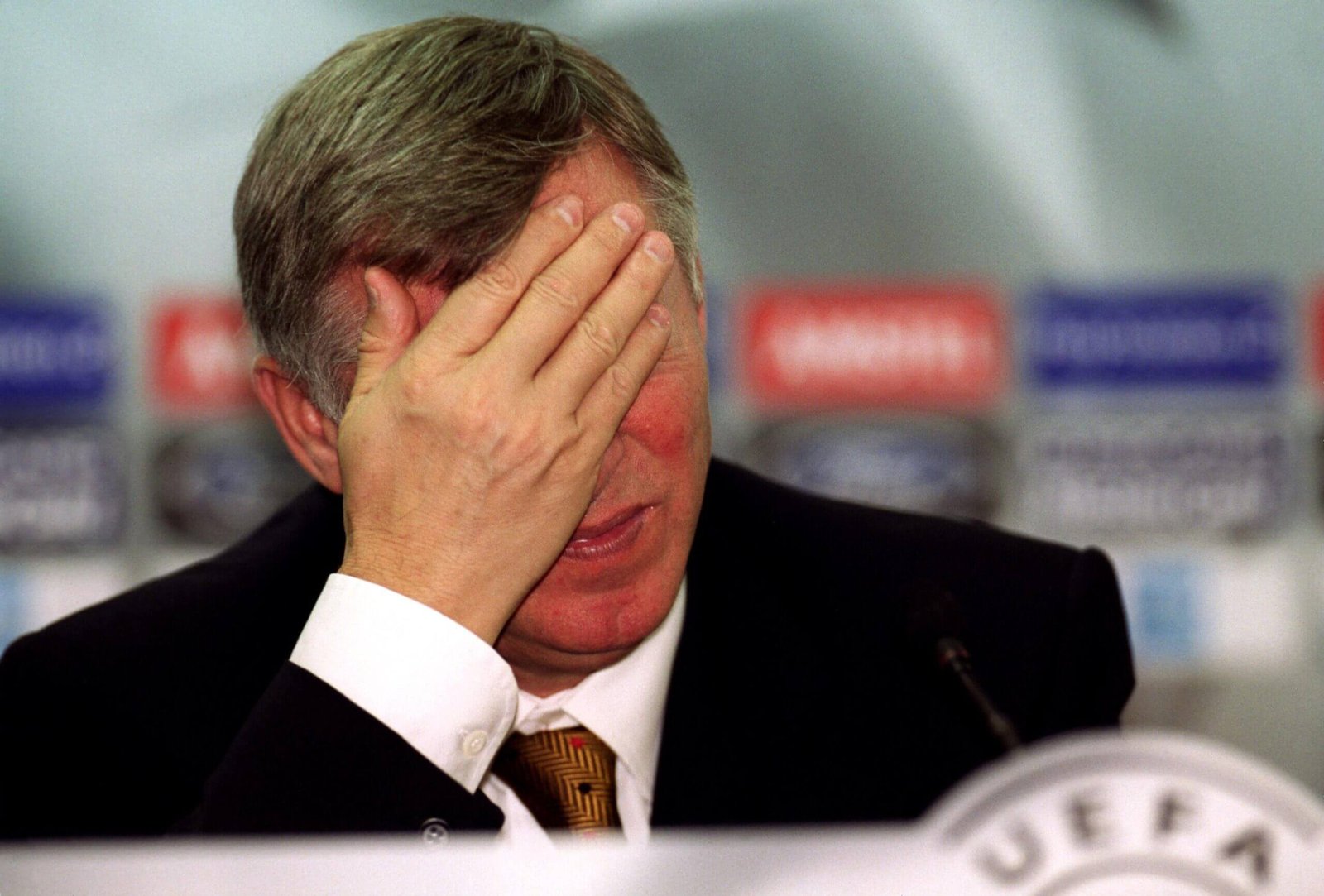

Ferguson after a September Champions League defeat in a troubled season (Jon Buckle/EMPICS via Getty Images)

Coming from Ferguson, the admission that “I took my eye off the ball” was staggering, as was his claim that many of his players “put their tools away” when they felt he was leaving.

It seemed rather damning of all concerned, but Ferguson felt it was simply human instinct — and likewise, the way his team rediscovered their purpose when he announced in February 2002 that he would be staying after all (although, looking back, perhaps the corner had been turned before that).

Roy Keane has suggested this explanation was a red herring; the bigger issue, he said, was that some of his team-mates simply lost their hunger after winning three Premier League titles in a row.

Gary Neville disagreed. “We’d been a machine trampling over our rivals, but now every week brought another story about the club’s future, who might take over and what role (Ferguson) would play,” the former Manchester United and England defender wrote in his autobiography, Red.

“Most of the talking went on outside the club, but its unsettling effect was indisputable. There was no waning of the manager’s authority — not by a fraction — but I guess subconsciously you start to waste energy thinking about what lies ahead and you can’t afford even the slightest distraction when you are in the business of chasing trophies.”

Distractions? Uncertainty? Outside noise? Managers hate that. They hate it in particular when the noise relates to their own position (except, perhaps, in certain cases where managers have appeared to amplify the noise in the belief it will strengthen their hand in contract negotiations).

There were times early in that 2001-02 season when Ferguson was happy to discuss his retirement plans and his hopes of a glorious finale at Hampden Park, but he came to resent being asked about it weekly (“So, Sir Alex, your final trip to Anfield/Highbury…”, “Does it make you even more determined to…”).

So, too, you suspect, will Klopp — particularly as the weeks go on and the stakes are raised even higher.

If Ferguson’s aborted retirement plan in 2002 is often cited as Exhibit A in this case, it is because his tenure at Manchester United shaped an era and so many fundamental principles of modern English football culture. The rise and fall of the Old Trafford empire offers so many case studies of what to do and, over the past decade, what not to do.

Exhibit B? It is less clear, precisely because it has become so rare in English football for a manager to signal his departure months in advance.

There was a deeply uncomfortable situation at Tottenham Hotspur last season after Antonio Conte entered the final months of his contract with neither party showing much appetite to strike a new deal. Relations with his players and the club’s management became strained and, ultimately, untenable as his contract was terminated early.

A more low-key example came in 2005 when Kevin Keegan made clear he had no intention of extending his contract at Manchester City beyond the end of the season. He and the club were initially content with that arrangement, but then results took a downward turn and players began to complain that they were in a state of limbo. David James spoke of an “area of uncertainty”. “There has to be clarity,” the goalkeeper said.

Soon enough, there was. Keegan, like Conte, agreed to depart two months before the end of the season.

Conte’s final months a Spurs were uncomfortable for all (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images)

The “lame duck” scenario is one clubs are desperate to avoid. Even when a contract is running down and it becomes clear the time has come for a parting of the ways — see Roy Hodgson at Crystal Palace at the end of the 2020-21 season (and quite possibly at the end of the 2023-24 season) — clubs and managers prefer to leave an announcement as late as possible for fear of tools being downed, to use Ferguson’s expression.

But Keegan’s Manchester City and Hodgson’s Palace were drifting in the way that mid-table teams often do. Conte and Tottenham was a loveless marriage that had run its course. Those three situations were radically different to that facing Klopp and Liverpool — and Hayes and Chelsea — in 2024.

Liverpool are top of the Premier League, through to the Carabao Cup final and the last 16 of both the FA Cup and the Europa League. Klopp’s announcement was followed by emphatic wins over Norwich City (5-2) in the FA Cup and Chelsea (4-1) in the Premier League.

Defeat at Arsenal on Sunday came as a jolt — and perhaps a reminder, if any were needed, that it is not as simple as being swept along on a wave of emotion in Klopp’s final months in the job.

But nor was it a performance that suggested a group of players might be “downing tools”. Klopp simply called it a “bad day at the office”. We have all had those. Even professional athletes.

“Ultimately it comes down to human nature,” says performance psychologist Paul McVeigh, who played in the Premier League for Norwich City and Tottenham and won 20 caps for Northern Ireland. “In any workplace, when everyone can suddenly see an endpoint to a manager’s tenure, you might see people down tools or see a boost in performance and productivity.”

McVeigh never encountered that situation in his own career, but he is more sceptical of the “downing tools” theory in a sporting environment — unless, for example, morale was already low and it was a manager the players were desperate to be rid of, which certainly isn’t the case with Klopp or Hayes.

He feels a team in a trophy-challenging position would more likely be galvanised than inhibited by such an announcement. “Absolutely,” he says. “When they know something is coming to an end, it’s human nature to want to squeeze every last bit of performance in that finite amount of time you have left.

“Think of it like running on a treadmill. If you’re told to keep running and you don’t know for how long, it’s human nature to hold something back.

“Whereas if you’re told to run as fast and as hard as you can for just 12 more minutes, it can concentrate your mind on that task because you have that endpoint in view. It becomes a closed loop rather than an open loop.”

When Ferguson announced he would retire at the end of that 2001-02 season, one prominent football figure urged Manchester United to get rid of him immediately.

In fairness to Lazio’s then-owner Sergio Cragnotti, he was still bruised by his experience with Sven-Goran Eriksson the previous season. Eriksson signed a deal in October 2000 to take over as England coach at the end of that campaign, but results nosedived and he ended up being released from his contract in January to take the England job.

Cragnotti remained on good terms with Eriksson, but he was left to reflect that “the players lose their way when they know the coach is leaving. The team are like sailors on a ship who know the captain is about to jump”.

But nobody would say Bayern Munich’s players “lost their way” in 2012-13 when coach Jupp Heynckes was serving his notice before handing the reins to Pep Guardiola.

From the moment the announcement was made, Bayern played 27 matches in all competitions: 25 wins, one draw and one defeat. “We have to do it for the coach,” winger Franck Ribery said — and they most certainly did that, winning the Bundesliga, the DFB-Pokal and, best of all, the Champions League, beating Klopp’s Borussia Dortmund team 2-1 in the final at Wembley, setting a standard that even Guardiola could not match in Munich over the next three seasons.

Guardiola’s departure from Bayern in 2016 was announced six months in advance, even if confirmation of his move to Manchester City came slightly later. Bayern cruised to a fourth consecutive Bundesliga title and another German Cup success, beating Dortmund on penalties, but Guardiola’s hopes of a perfect ending were dashed when they lost to Atletico Madrid in the Champions League semi-final.

But when we are talking about a club who have won league titles as a matter of routine, under various coaches, before facing the unpredictability of the Champions League knockout stage, it is hard to make sweeping statements about what works or doesn’t work.

Heynckes is a hugely significant figure in Bayern’s history, having won nine trophies across three spells as a coach, but that treble triumph in 2013 came at the end of a two-season spell; his influence across the club was nothing like as great as Ferguson’s at Manchester United or indeed Klopp’s at Liverpool.

Xavi is to leave Barcelona a year after winning La Liga (David Ramos/Getty Images)

That is the difficulty when it comes to drawing comparisons. At the big clubs in Germany, Italy and Spain, it is rare for coaches to stay so long and gain such power and influence as can happen (albeit increasingly rarely) in England. Diego Simeone at Atletico Madrid is a rare exception. Guardiola’s three-year stint at Bayern was the longest of any coach since Ottmar Hitzfeld left in 2004; his four years in charge of Barcelona were the longest of any coach since Johan Cruyff departed in 1996; Vicente del Bosque’s three-and-a-half-year tenure at Real Madrid (1999-2003) is the longest of any coach since the great Miguel Munoz stood down in 1974.

Xavi’s looming departure from Barcelona is big news because of the timing of the announcement, but he was expected to leave at the end of the season anyway. If he gets the “reaction” he has demanded, it will be seen as a masterstroke. Back-to-back wins over Osasuna and Alaves are encouraging, but bigger tests await. If the inconsistency of previous weeks returns, there will no doubt be calls for him to leave sooner rather than later.

The cult of the manager — as opposed to respect for the art of coaching — is so much more powerful in British football, where he is seen less as a trainer than as an all-powerful figurehead. That has changed over time in the post-Ferguson world, but even in recent years, there has been an air of overriding control about the Premier League’s leading coaches: Guardiola at Manchester City, Klopp at Liverpool and even, increasingly, Mikel Arteta at Arsenal, Unai Emery at Aston Villa and Eddie Howe at Newcastle United.

Klopp’s departure from Dortmund in 2015 after seven years in charge was a rare case in German football of a managerial move that felt seismic — even though the season in question was a struggle. He made the announcement in mid-April, hoping to end the campaign on a high.

The DFB-Pokal offered the prospect of a happy ending, but Dortmund lost 3-1 to Wolfsburg. “Winning today would have been too kitschy, too American,” he said afterwards as if to say it would have been too good to be true.

Klopp has admitted he would have preferred to follow the Ferguson (2013) approach and keep his departure from Liverpool under wraps.

“In an ideal world, I wouldn’t have said anything to anybody until the end of the season, (then) win everything and then say goodbye,” the Liverpool manager said. “(But) in the world we are living in, it’s not possible to keep things like this a secret. It’s maybe a surprise that we could keep it (secret) until now.”

The reasons for going public are obvious. It brings clarity and an element of transparency to a situation — and, while the cloak-and-dagger approach has potential benefits as far as a team’s immediate ambitions are concerned, with the benefit of many years’ hindsight, it made things harder when it came to lining up a successor for Ferguson.

By the time Manchester United were ready to hold talks over potential successors to Ferguson, Guardiola had committed to Bayern Munich and Manuel Pellegrini, Jose Mourinho and Carlo Ancelotti were already in advanced talks with Manchester City, Chelsea and Real Madrid respectively. David Moyes, then at Everton, emerged as the leading contender almost by default. The Moyes appointment didn’t work. The stability the club maintained in Ferguson’s final months has been missing ever since.

Liverpool are now seeking a replacement for Klopp (Shaun Botterill/Getty Images)

In other words, the perfect managerial departure probably doesn’t exist. Go quietly as Ferguson did in 2013, keeping it all in-house until the last possible moment, and succession planning can be much harder. Go public early, as Ferguson did in 2001-02 and Klopp, Xavi and Hayes have done this season, and there is a danger that the noise can become overwhelming.

That is all it is, though. Noise.

“Dealing with distractions and uncertainties is just part of your life as an athlete,” McVeigh says. “When you think of the life of a professional athlete, you can probably count the number of certainties — things you’re in total control of — on one hand. You’re constantly dealing with noise and uncertainty. The best athletes are the ones who don’t let it affect performance.”

When Liverpool captain Virgil van Dijk faced the media for the first time since Klopp’s announcement, he made some of the right noises but also said he was unsure about the future. It was honest but perhaps not entirely on-message.

There followed another interview with Liverpool’s official media channels, this time more of a rallying call. “We all want to achieve so much,” he said. “It will maybe even give you an extra boost to — or maybe enjoy it even more together and make the last part of the season, the last bit of the manager’s time at the club, the best he (Klopp) has ever had. That’s what we strive for and that’s why it’s business as usual.”

His defensive partner Ibrahima Konate said of Klopp’s departure that “I have to give my life for him” for the final four months of his tenure.

Van Dijk touched upon the uncertainty at Liverpool (Marc Atkins/Getty Images)

Millie Bright, captain of the Chelsea women’s team, said she and her team-mates were “gutted” to learn in November that Hayes (“a mentor, a coach, a friend, a life coach”) will leave at the end of the season. “But I think, knowing Emma, she wants us to do everything the same, regardless of her departure,” Bright said. “If we react any differently, I’m sure we’ll get a battering from her.”

The immediate response to Hayes’ announcement was emphatic: four straight victories in the WSL, scoring 19 goals in the process. Then came the jolt of a 4-1 defeat at Arsenal, which Hayes said was “as bad as I’ve seen us for a long time”, and a disappointing 0-0 draw at home to BK Hacken in the Champions League.

Since then it has been eight straight wins in all competitions: normal service resumed. But in all of these cases, there is still the likelihood that people will try to link any uplift or any downturn in results directly to the impact of an outgoing manager’s announcement.

The narrative is easy and at times irresistible. There might even be times when it is accurate. In a sport of small margins, the impact of a manager’s announcement could end up making all the difference — positive or negative — or none whatsoever.

It will be emotional. There is a fine margin between harnessing that emotion and energy and being overwhelmed by it. Klopp and Hayes, in different ways, will hope to strike that balance while accepting the reality that, even then, a single, unrelated moment of individual brilliance or a mistake might determine a season and, ultimately, shape a legacy.

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here