It is 66 years since the Munich air disaster robbed English football of one of its greatest young teams.

Eight Manchester United players from Sir Matt Busby’s brilliant side were killed when the plane carrying them crashed on February 6, 1958, and two more were so badly injured they never played again. Fifteen others aboard also died.

To mark the anniversary, and as a tribute to those who were lost, The Athletic has produced a special series of pieces. Read the others here:

As the snowflakes fluttered across the airfield, the temptation was too much for two of the younger players in Manchester United’s travelling party.

Eddie Colman, 21, was the first to scoop up a handful of snow from the ground. David Pegg, 22, soon joined him. The two were best friends and suddenly snowballs were being launched through the air. Hours later, both would be dead, along with 21 other passengers aboard British European Airways Flight 609.

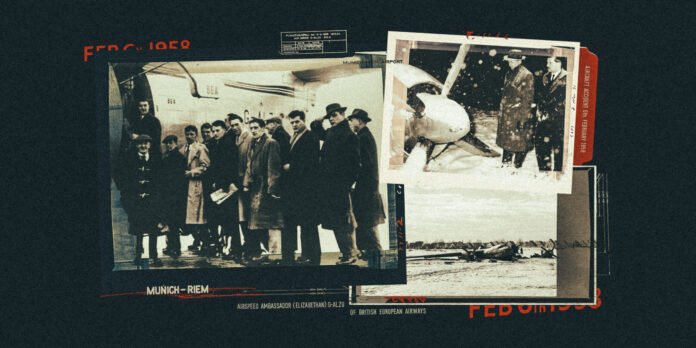

It was early afternoon on Thursday, February 6, 1958, and the twin-engined Airspeed AS57 Ambassador — a model known as The Elizabethan — carrying manager Matt Busby and his United players, had just landed at Munich-Riem Airport for refuelling on its way back to England from the team’s European Cup quarter-final second leg against Red Star Belgrade in the old Yugoslavia (now Serbia).

Spirits were high. The previous night, United had overcome their Yugoslav opponents, drawing 3-3 with two Bobby Charlton goals and another from Dennis Viollet to progress 5-4 on aggregate. The ‘Busby Babes’, with an average age of 22, were in the semi-finals for the second successive season and, in the warmth of the terminal in Munich, somebody started singing the Dean Martin classic “Baby, It’s Cold Outside”.

Colman, nicknamed Snake Hips because of the way he used to shimmy past opponents, fetched a round of hot drinks. Others went to buy presents for their loved ones. Johnny Berry, one of the senior players, was keeping the shop assistant busy behind the toy counter, winding up mechanical cars to pick out the ones that his three young boys would like best.

“They were a happy group,” Frank Taylor, the only survivor among the nine journalists aboard Flight 609, recalled in his book, The Day A Team Died. “Anybody who was anybody in British football was quite convinced that Matt Busby had brought to Old Trafford the most talented group of footballers ever seen at one club.”

The Elizabethan was so highly rated within the aviation industry it had been used to fly Queen Elizabeth II to her international appointments. The passenger cabin was made up of 10 four-seat rows – the first four facing the tail, then six facing the cockpit – and by the time the plane was ready to leave Munich for home it had a total of 44 people aboard.

The BEA Elizabethan airliner which crashed at Munich (PA/PA Images via Getty Images)

Two card schools were underway, involving nine players. One had Berry, Roger Byrne and Liam Whelan sitting across from Ray Wood and Jackie Blanchflower. The other was a four-hander involving Pegg, Bill Foulkes, Kenny Morgans and Albert Scanlon.

Charlton, then 20, was one of United’s “golden apples” – to use the phrase of coach Jimmy Murphy – and had already shown the uncommon talent that led to him being recognised as one of the greatest footballers in the history of the sport. He was sitting towards the front beside Viollet, another regular source of United’s goals. Harry Gregg, the goalkeeper, was on the other side, spread across two seats so he could have a well-deserved nap, having withstood a fierce second-half onslaught from Red Star in the JNA Stadium that had seen them score three unanswered goals.

Busby, whose managerial achievements by that stage already featured three league championships and an FA Cup, looked tired and grey. The Scot was one of the doyens of his profession, in his 13th year as United’s manager, but he had been in hospital a few days earlier for an operation on some varicose veins in his leg. Not a major procedure, perhaps, but one that had sapped his energy.

He and his staff were in the middle rows and, behind them, there was football’s original Boy Wonder, Duncan Edwards, a player still often cited as one of the greatest young talents England has ever produced. Also in that section were Colman, Mark Jones, Tommy Taylor and Geoff Bent.

The back rows were taken up by reporters, many of whom were looking forward to the annual Manchester Press Ball that evening.

The propellors roared into action, the plane began picking up speed and the slush started to fly off the wheels. But it quickly became apparent something was wrong. The co-pilot, Kenneth Rayment, had detected excessive boost pressure, or ‘surging’, and knew it risked the engines malfunctioning in midair.

The brakes were applied with enough force to pitch one of the stewards, Tommy Cable, into the seat in front of him. It was his colleague, Margaret Bellis, who announced there was a technical fault and that everything would be fixed as quickly as possible if everyone could kindly disembark and return to the terminal. The plane had been on the move for 40 seconds.

For the passengers, there was a bit of consternation and all the sorts of questions and theories that you would expect in those circumstances. Had the engine cut out? Was it snow on the wings? Any sign of the weather letting up?

They were entitled to have a few concerns, given that it had been less than a year since another British European Airways aircraft, flying in from Amsterdam, had crashed near Manchester’s own airport, with the loss of 22 lives.

Busby and his players also knew from experience, collectively and individually, that “technical fault” was just the catch-all explanation for any sort of hitch or mishap preventing a plane from leaving on time. In the Spanish city of Bilbao a year earlier, United’s flight was not going anywhere until the entire team disembarked to clear ice and snow from the wings. Gregg, a Northern Ireland international, had once returned from a game in Belfast on a plane that lost a propellor in midair.

Harry Gregg had already endured a frightening experience on an aircraft (Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

As everyone trooped back into the terminal, Alf Clarke, the Manchester Evening Chronicle’s correspondent, estimated it would be two to three hours before they were ready to take off. Clarke had flown in the First World War and, as such, had a bit of gravitas among his fellow passengers.

Jones, the centre-half, headed to the duty-free shop, where he bought himself a St Christopher medal — the patron saint of travellers. More coffees were ordered and there was considerable surprise when, before they could be finished, the call came for everyone to return to the aircraft.

Again, the passengers took their seats, strapped themselves in and readied for take-off. Again, the nose wheel refused to lift. The brakes went on and the plane juddered to a halt on a layer of white-brown slush. This was the second failed attempt to get off the runway. And this time, one voice rose above the others.

It belonged to Frank Swift, the former England goalkeeper, whose 16 years at Manchester City had involved winning the 1936-37 championship and, two years earlier, the FA Cup. Aged 44, Swift was on the plane as part of a new career writing about football for the News of The World. He was a big, amiable man, but there was unmistakable alarm in his voice.

“What the hell is going on?” he was shouting.

The prospect of getting back to Manchester appeared to be receding as the passengers squelched to the terminal for a third time.

Those two aborted take-offs had been unnerving for everyone and, as the players talked between themselves about the possibility of having to stay in Germany overnight, Edwards sent a telegram to his landlady in Manchester. His words made it clear he had given up hope of a return that day. “All flights cancelled. Flying tomorrow, Duncan.”

Again, though, an announcement came for everybody to return to the plane. It had been very quick, which added to the sense of unease. Could they really have fixed the problem in so little time? Gregg and Blanchflower had not even had time to spark up their cigarettes. Blanchflower stuck one behind his ear and the pair of them exited the terminal to head into the snow again.

“The weather was as bad as I had ever seen it on my football travels,” Charlton would later say. “There were six or seven inches of slush on the runway.”

Players, staff and journalists prepare to board the plane in Manchester en route to Belgrade (AFP via Getty Images)

Nobody, though, challenged the decision to make a third attempt. Busby wanted the players to get back to Manchester so they could have a full day’s rest before playing Wolves that Saturday. The pilot, James Thain, had been given the clearance to try again and, if any of the passengers thought it was crazy, nobody had the gumption to speak up. As Gregg would later say: “Sometimes it takes a brave man to be a coward.”

Instead, the players were counted back on, one by one, and at 2.59pm a radio message crackled up to the control tower: “Are we cleared?”

On board, there was a mix of bravado and butterflies. Pegg, a brilliant, elusive left winger who had tormented Real Madrid in the previous season’s European Cup semi-finals, announced he did not want to play cards anymore. “I don’t like it here, it’s not safe,” he said, moving to the rear of the plane to find a seat near Colman.

“That’s right, lads, this is the safest end,” Swift called out.

Byrne, United’s captain, did not like flying at the best of times. He tried to make light out of it and joked that it was “all or nothing now”. Berry, another reluctant flyer, seemed gripped by fear.

Gregg, experiencing his own sense of foreboding, tried to crack a few jokes. He had a copy of a book called The Whip, a titillating piece of fiction that was regarded at the time as a bit risque. “It was playing on my conscience,” he would say. “I thought, ‘If anything happens here and I’m reading this, it is straight to hell for me’.”

In the cockpit, Thain glanced at the airspeed indicator. At 117 knots (135mph), he called out “V1” – Velocity 1, the point at which it was unsafe to abandon take-off. In usual circumstances, the next step would have been to call “V2” at 119 knots, the speed required for take-off. But that was the moment the needle started dropping. The plane – coded 609 Zulu Uniform (G-ALZU) – had become a deathtrap.

Suddenly, it was 112, then 105. Thain was banging furiously on the throttle, trying to do something – anything – to get some more power from the two engines.

When he next looked up, he could see they were running out of runway. There was a road ahead, a farmhouse, a perimeter fence, some trees and a lot of snow. In that split-second, he and his co-pilot knew disaster was imminent.

“Christ,” shouted Rayment. “We aren’t going to make it.”

For reasons he could never fully explain, Gregg had already loosened his tie and unfastened the top button of his shirt.

As fear washed over him, he slid his frame downwards in his seat, preparing for the impact. Foulkes, seated in front of him, was also bracing himself. Someone began to laugh, in a nervous kind of way. “What are you laughing at?,” Berry shouted out, obvious fear in his voice. “We’re all going to get f***ing killed here.”

United players (from left) Bill Foulkes, Kenny Morgans, Ray Wood and Dennis Viollet, six months after the crash (Keystone/Getty Images)

The plane kept going, speeding past a red outbuilding that it had stopped almost opposite on the previous two runs.

Staring out of the window, Charlton could see field after field flashing past. He knew this could not continue. Then the 22-year-old Whelan, a devout Catholic from the Republic of Ireland, said something that over the years would be a comfort, of sorts, for his family in Dublin.

“If this is death, I am ready for it,” he said.

Thain, a day short of his 37th birthday, knew he had to take emergency action. The pilot shouted “undercarriage up” and retracted the wheels, so the plane could slide on its belly and, in theory, come to a quicker stop. There was a bounce, a change of motion and, briefly, a sense among some of the passengers that they might be airborne.

In fact, the plane never left the ground. It had skidded off the runway and, at 3.04pm, the final call came from the stricken Elizabethan.

“Munich, from B-Line Zulu Unif– …”

The words stopped abruptly. All that was left was a howling, whistling noise and then, audible from the control tower, a succession of terrible bangs.

All these years later, it is fair to say the death count would not have been so devastating if safety precautions which are standard today were applied in 1958.

Hypothetical, perhaps, but there may not have been any fatalities at all if the fencing had been further back from the runway, or if there had not been so many buildings in close proximity — including a wooden hut containing a truck loaded with drums of fuel. When the plane was torn apart, one section careered into that hut, creating a fireball.

As the plane crossed a road, Thain could see there was not enough room to get between a farmhouse and a large tree. Inside that house, Anna Winkler was sewing in the front room when she heard the terrifying sound of an out-of-control aircraft heading straight in her direction.

Still travelling at high speed, the left wing of the plane struck the farmhouse. That wing was torn off and parts of the tail unit, too, but the bulk of the plane continued on its deadly path. Fuel sprayed out of the ruptured wing tanks and the house was engulfed in flames. As the fire took hold, Winkler had to throw two of her young children into the snow. A third, aged four, escaped through a window.

Foulkes, one of the survivors, felt “a sickening thud … and then another one, and then another one, and then a terrific crash and then we were spinning all over the place.” He saw “sky, and then blackness.”

Busby recalled how time seemed to stand still. “We sped on and on and on and my thoughts sounded just like that – ‘on and on and on and on’ – until they changed to ‘too long, too long, too long, too long.’ We were not going up. I threw out my arms in a pathetic attempt at self-protection.”

Matt Busby in hospital in Munich (Keystone/Getty Images)

Charlton bent his head down and braced himself for the impact. “I didn’t hear the semblance of a scream. There had just been a vast and empty silence in the plane. I suppose we were in shock, overwhelmed with disbelief. The last thing I remember, before coming round away from the plane, was the terrible rending noise of metal on metal.”

The next collision was a tree ripping open the cockpit on Rayment’s side. What was left of the undercarriage had been torn away and a number of passengers got thrown into the snow. Busby was one of them, Charlton another. Blanchflower was catapulted out of the top of the plane. When he tried to pick himself up, checking each limb was still intact, he thought at first he must have been paralysed. The reason he could not move was because Byrne, still strapped into his seat, was across his legs. He was dead. Blanchflower lay with his team-mate in profound shock, trying to take it all in, watching the seconds tick by on Byrne’s watch.

Spinning and lurching completely out of control, the aircraft hurtled on. A lorry driver on the nearby autobahn saw a wheel fly off and shoot in his direction. The collision with the fuel truck had ripped open the starboard fuselage. The plane slithered on for a further 70 metres, its remaining wing felling trees like a giant scythe. Then, finally, the cacophony of tearing and breaking metal ended.

Fifty-four seconds after the throttle was opened, the once sleek, elegant Elizabethan came to a standstill as a broken, shattered wreck.

Wreckage of United’s airliner in the Munich snow (Mirrorpix via Getty Images)

“Less than a minute previously, I had been sitting in the company of the young kings of British soccer,” Frank Taylor wrote. “Now they lay dead or dying, or brutally injured and dumbly shocked by the tragedy which had hit them.”

“No one cried out,” another survivor, Daily Mail photographer Peter Howard, said afterwards. “No one spoke, just a deadly silence.”

“The whole aircraft was enveloped with flames,” Thain recalled. “We seemed to be spinning all over the place. There was a tremendous noise and then, quite suddenly, no noise at all. Absolute quiet; almost uncanny.”

When Gregg opened his eyes, he could “feel the blood coming down my face … I didn’t dare put my hand up because I thought the top of my head had been taken off, like a hard-boiled egg.”

Looking through a hole in the buckled, broken fuselage, the first person he saw was Bert Whalley, United’s youth team coach, lying beneath him. “He was wearing a blue shirt and a blue cardigan. It was Bert who had nurtured so many of the young players. He was motionless, his eyes were open and there wasn’t a mark on him. Somehow, I still knew he was dead.”

Recovering his wits, Gregg kicked the hole bigger and crawled outside to find four or five fires burning around the plane. Thain had already got out and was shouting to, “Get away! Go on, run! Get away!”, before the whole thing exploded.

Dazed and concussed, Gregg stood for a moment, taking in the devastation and the stench of fuel. Every bit of common sense was telling him to flee to safety. But that was not an option he was willing to take. He started climbing back into the wreckage: “There’s people alive in here.”

What he had to see in there was almost unspeakable. For Gregg, however, sheer courage took over as he set about looking for survivors. He heard a baby’s cry and followed the noise until he found 22-month-old Vesna Lukic, daughter of a Yugoslav diplomat in London. Her mother, Vera, was nearby. Gregg managed to haul them, both badly injured, to safety.

“To me, Harry Gregg has always been Superman,” Vera would say many years later.

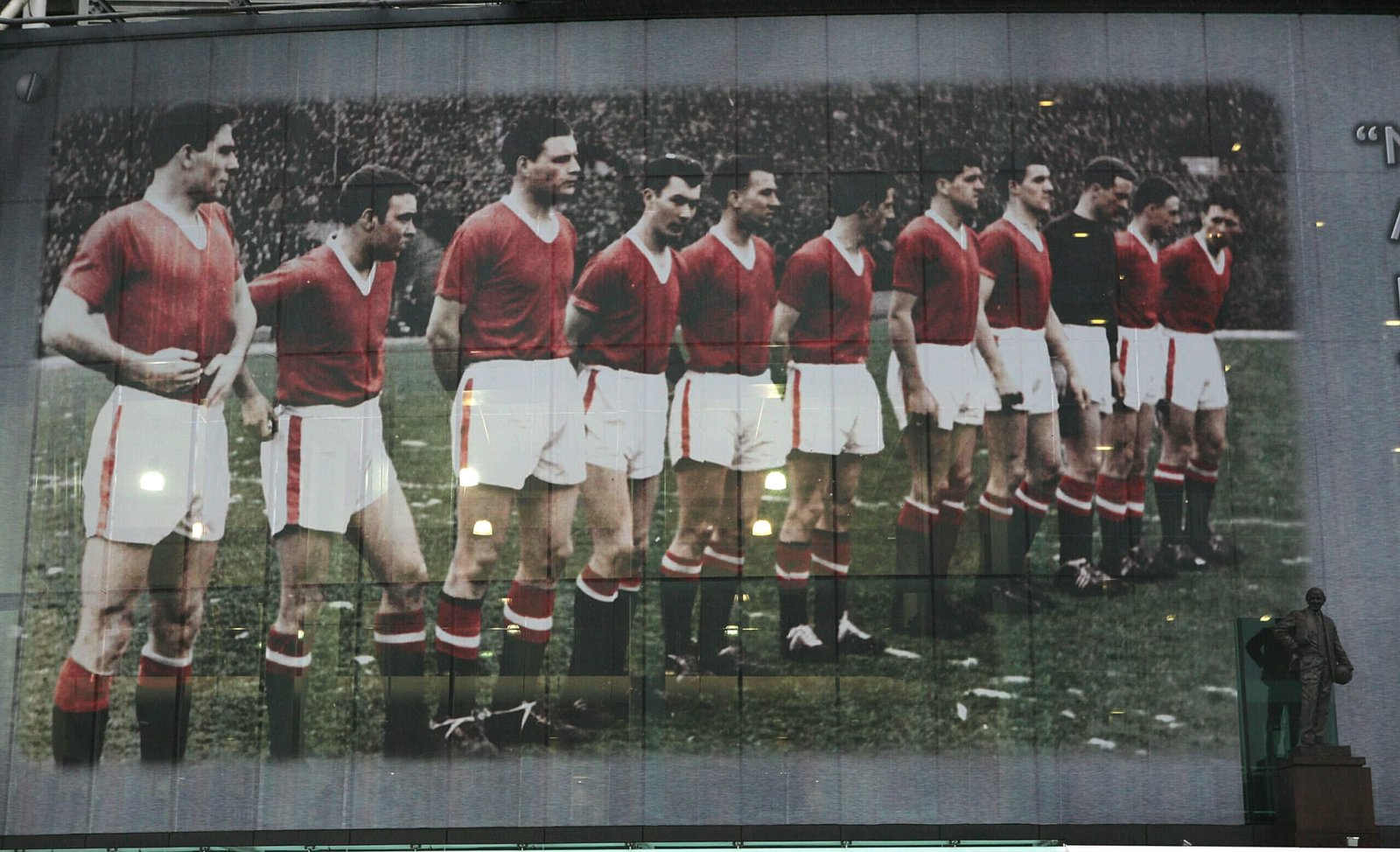

A picture of the ‘Busby Babes’ before their last game together in Belgrade, outside Old Trafford (Getty Images)

Foulkes, a 26-year-old centre-back, had woken up to find fires burning and Thain fighting the flames with an extinguisher. His first instinct was to run and, to begin with, that is what Foulkes did until, recovering from his initial panic, he returned to the wreckage and joined in the rescue operation.

He found Busby, sitting up on one arm, semi-conscious and in severe shock, complaining about the pain in his legs. United’s manager, then 48, was ice-cold, clutching his chest. Foulkes put a coat over him. He and Gregg vigorously rubbed Busby’s hands until expert help arrived.

“Bobby Charlton was close by, still strapped in his seat,” Foulkes recalled. “He seemed to be slumped over and I thought he’d had it but, suddenly, as if he was waking out of sleep, he took off his safety belt, stood up and walked over to us. Dennis Viollet, who was also sitting in his seat, did exactly the same thing and I began to think everyone was all right.”

Thirty yards further on, the reality became shatteringly clear when Foulkes found Byrne folded over his seat as if his back was broken. Byrne, the oldest player to die, aged 28, was one of the most stylish left-backs ever to play for England. Foulkes knew straight away that United’s captain was beyond help.

Thain had returned to the cockpit and used an axe to free his co-pilot, whose legs were broken in several places and jammed in the wreckage of the pedals. Rayment, who had fallen into unconsciousness, was taken to hospital, where he died five weeks later from head injuries. Steward Cable was also killed.

Twenty of the passengers were dead before the ambulances arrived, their bodies either flung from the fuselage or pinned under the chaos of metal and fire. They included seven members of the team – Byrne, Bent, Colman, Jones, Pegg, Taylor and Whelan – that had won the league championship the previous season.

Three club employees had also lost their lives – Whalley, secretary Walter Crickmer and trainer Tom Curry – as well as two other passengers, United supporter Willie Satinoff, who was a friend of Busby’s, and travel agent Bela Miklos, who had organised the trip to Belgrade.

The eight journalists to die were Swift, Clarke, Henry Rose (Daily Express), Eric Thompson (Daily Mail), George Follows (Daily Herald), Don Davies (The Guardian), Tom Jackson (Manchester Evening News) and Archie Ledbrooke (Daily Mirror).

That their colleague, Taylor, survived was almost certainly because he had chosen, on a whim, to sit at the front of the plane. But his list of injuries reflected the carnage. The left side of his head had been sliced open, requiring 21 stitches. He had a double fracture of his collar bone, nine broken ribs, an obliterated elbow joint and a leg so badly smashed the tibia and fibula were protruding through his trousers like broken cricket stumps. It was 18 months before Taylor could walk again.

Scanlon, who had been found under a wheel, had a fractured skull and head injuries of such severity that Gregg had to stop himself from vomiting when he saw his team-mate. Others were gashed and concussed but intact. Morgans, an 18-year-old, was pinned in the wreckage – unconscious, yet still alive and, incredibly, without a mark on his face from the heap of jumbled metal around him.

Albert Scanlon suffered serious head injuries (Keystone/Getty Images)

They were the lucky ones. Most of the people who died at the scene, either in the cabin or scattered across the fields and rough ground, had been sitting towards the rear of the plane. They, like Pegg, had assumed they would be safer in the back rows.

Edwards, who was 21, had been seated further forward.

He was a colossus of a man, a full England international from the age of 18, and the doctors treating him said it was a miracle he had survived. But he was in a bad way: damaged kidneys, a collapsed lung, a broken pelvis, multiple fractures of his right thigh, crushed ribs and a litany of internal injuries.

Edwards spent 15 days in Munich’s Rechts der Isar hospital before Charlton, rehabilitating at home, heard the words he had dreaded. It was his mother, Cissie, who told him, placing her hand on his shoulder and whispering, “Big Duncan has gone.”

The event known to generations of United supporters as simply “Munich” had destroyed the nucleus of what promised to be one of the greatest teams in English football history. That team had the world at their feet, playing beautiful football and destined, it seemed, to dominate the sport for the following decade.

And, in four and a half minutes, all that optimism and innocence had been replaced by tragedy and loss.

The Deceased

Players

Bent was a talented defender whose first-team chances were limited by the presence of the exceptional Roger Byrne. He travelled to Belgrade as back-up to Byrne, who was struggling with an injury, and privately complained to his wife about going. He died before emergency services could arrive at the runway.

One of England’s finest defenders, who won 33 caps, Byrne was the captain of the ‘Busby Babes’ and the oldest player to be killed at Munich. His wife, Joy, whom he had married the previous year, had just discovered that she was pregnant with their first child: Byrne was unaware when he died.

The youngest victim at Munich, Colman was a skilful wing-half who earned the nickname ‘Snakehips’ because of his ability to bodyswerve around opponents. A local boy who grew up a few minutes’ walk from Old Trafford, he – like many of his teammates who died at Munich – is memorialised. In Colman’s case, he now has an accommodation block at the University of Salford named in his honour.

Edwards – a native of Dudley in the West Midlands, where a statue commemorating him stands today – was widely recognised as one of the greatest talents of his generation, able to play in almost any position. Strong, tough but also supremely skilled, Edwards had already become the youngest player to compete in the English top flight, and his country’s youngest capped player since the Second World War. He survived the initial crash but died from his injuries two weeks later.

The statue to Duncan Edwards in Dudley (Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

Jones, the son of a Yorkshire miner who trained as a bricklayer, won two league titles with United after breaking into the team regularly in the mid-1950s. His wife, June, was pregnant with their second child, a girl.

A fixture in the United side after making his debut as a 17-year-old in 1952, Pegg – a close friend of fellow Yorkshireman Tommy Taylor – had been displaced as the regular starter by Albert Scanlon a few months before he died. He also won one England cap.

A prolific scorer, with 131 goals in 191 games for United, Taylor was a formidable presence – supreme in the air, powerfully built and with a fearless attitude. Busby had rejected a £65,000 offer from Internazionale in 1957 – a huge fee at the time – and he had also averaged almost a goal a game for England. Taylor, a former miner, had just become engaged to his partner, Carol, when he died.

Born in Dublin, Whelan joined United in 1953 as an 18-year-old and was another prolific forward, scoring 52 goals in 98 games – a record which attracted transfer interest from Brazil. Whelan was a nervous flier and was reported to have said, “If this is death, I am ready for it,” before the plane’s fateful failed take-off in Munich.

Club staff

A United stalwart of 32 years, Crickmer had twice been the club’s manager as well as its secretary. A key figure in establishing the club’s youth policy, he was in charge between April 1931 and June 1932, and then again from November 1937 to February 1945, a period which saw Old Trafford bombed by German war planes.

A former half-back, who made over 200 appearances for Newcastle United, Curry had been working as a trainer for Carlisle United before moving to Manchester United in 1934, working for manager Scott Duncan and then Matt Busby. He also had some responsibility for treating injured players at United, and his daughter remembered coming home to find first-teamers being attended to on the family’s kitchen table.

Whalley joined United as a player in 1934, after starting his career at Stalybridge Celtic. His playing career was interrupted by the Second World War but he trained as a coach and was appointed to United’s staff after an eye injury ended his playing career. He was named chief trainer in 1955, acting as an emollient foil to Busby’s fiery assistant, Jimmy Murphy.

Media

Alf Clarke

Newspaper:

Manchester Evening Chronicle

A Manchester resident all his life who had been a chorister at the city’s cathedral, Clarke spent his whole working life at the Evening Chronicle, covering United – the club he had supported since childhood – for 25 years.

Don Davies

Newspaper:

Manchester Guardian

Davies, who had been a prisoner of war in the First World War, worked for the BBC and Boy’s Own as well as the Manchester Guardian. His football writing came from a position of specialised knowledge: he had won international honours at amateur level in his youth.

The journalist who was first credited with using United’s ‘Red Devils’ nickname in print, Follows had started his career in the West Midlands before moving to Manchester. He was close friends with players Dennis Violett and Ray Wood.

Tom Jackson

Newspaper:

Manchester Evening News

Jackson had a celebrated career away from journalism, having worked in the Intelligence Corps during the Second World War, where he worked on tracking down Nazi war criminals. He became a full-time sports reporter and was widely seen as one of the finest reporters working on the club.

Ledbrooke, a veteran sports writer who worked in football and cricket, had been working on an article about Blackpool just before he was supposed to fly to Belgrade. Another journalist, Frank McGhee, had been lined up to take his place on the flight but he ended up making his deadline and boarding the plane.

One of the most celebrated journalists of his day, whose presence at matches would prompt signs to appear stating ‘Henry Rose Is Here Today’, Rose’s funeral attracted an estimated 4,000 people and a six-mile long procession to Manchester’s Southern Cemetery.

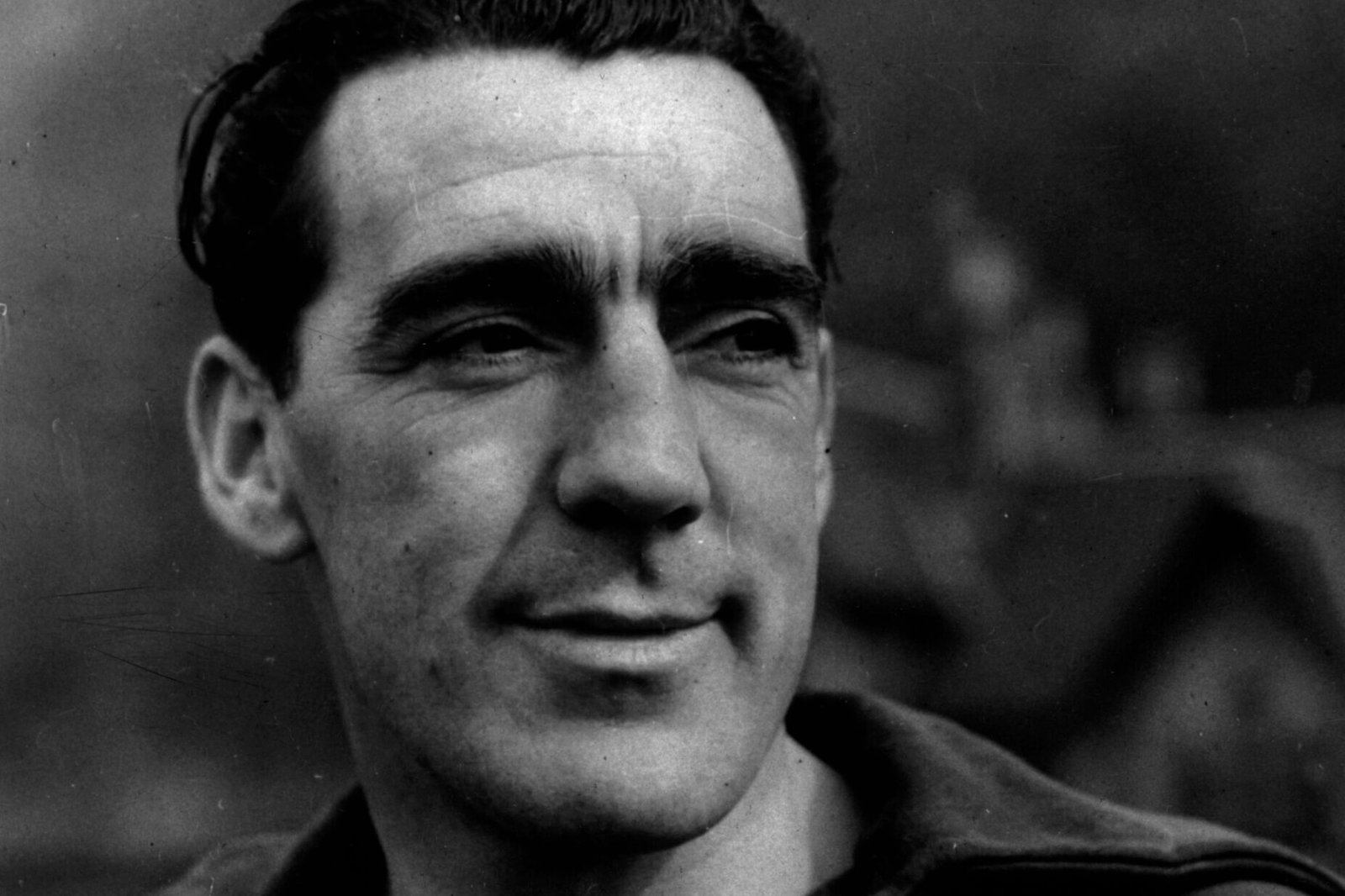

Frank Swift

Newspaper:

News of the World

A superstar presence in the press box courtesy of a glittering playing career for Manchester City and England, Swift had won the FA Cup in 1934 but fainted in the aftermath, prompting a concerned King George V to telegram him the following day enquiring over his health. Swift survived the initial crash but died on his way to hospital.

Frank Swift (Keystone/Getty Images)

A best-selling author, as well as a respected sports reporter, Thompson would also draw his own cartoons and sketches to illustrate his work. Renowned for his sense of fun and sartorial elegance, Thompson made a point of always wearing a bow tie to his reporting assignments.

Other victims

Willie Satinoff

Job:

Businessman, fan and friend of Matt Busby

The Survivors

Players/staff

Busby was twice read the last rites in hospital but had recovered sufficiently to attend the FA Cup final at Wembley three months later. He went on to rebuild the squad and win two league titles and a European Cup. He died in 1994, and remains revered as the godfather of the modern Manchester United.

A United stalwart who made almost 250 league appearances for the club, winning three titles, he suffered amnesia in the crash and only found out what had happened a month later. He suffered terrible injuries and never played again, going on to run a sports shop with his brother. He died in 1994.

The younger brother of Tottenham captain, Danny, Blanchflower played 117 games for United having graduated from the academy. He, too, was read the last rites after injuring his pelvis, arms and legs in the crash but recovered. He was forced to retire a year later, ultimately making a living as an accountant and after-dinner speaker. He died in 1998.

Jackie Blanchflower (Central Press/Getty Images)

Bobby Charlton

Position:

Midfielder/forward

Charlton was rescued from the wreckage by Harry Gregg but sustained only minor injuries – he was playing again within a month of the crash. He went on to become perhaps the most celebrated English footballer of all time, inspiring United to domestic and European glory and helping his country win the World Cup in 1966, the same year he claimed the Ballon d’Or. He went on to become a United director before his death last year, at the age of 86.

Foulkes’ only injury was a head wound caused by being hit by a gin bottle that had fallen out of an overhead locker. After helping search for survivors, he spent the night in a local hotel. He went on to make 688 appearances for United in a career that spanned 18 years in the first team and died in 2013, at the age of 81.

Gregg became known as the ‘Hero of Munich’ for his work in pulling survivors out of the burning wreckage. He played 11 days later against Sheffield Wednesday, keeping a clean sheet in a 3-0 win, and stayed at United until 1966. He later became a manager before dying in 2020, aged 87.

Morgans was the youngest player involved in the crash and the last survivor to be pulled from the wreckage: a journalist discovered him, five hours after the plane had come down. He spent three weeks recuperating in hospital but played for United before the end of the season. His form never truly recovered, however, and he moved into the lower leagues. He later worked as a pub landlord and ship’s chandler before his death in 2012.

Scanlon suffered serious injuries in the crash, including a fractured skull, broken leg and damaged kidneys. He did not return until the start of the following season, and left United in 1960. After retiring he worked as a security guard for a firm near Old Trafford, and a docker in Salford, before his death in 2009.

Viollet suffered head and facial injuries in the crash but was playing again before the end of the 1957-58 season. He was pivotal in United’s resurrection in the years that followed, scoring prolifically between 1958 and 1961 ahead of joining Stoke, where he made over 200 appearances. He went on to have a successful coaching career in the U.S. before his death from cancer in 1999.

Wood, best known for being injured during the 1957 FA Cup final, suffered only minor injuries in the crash but made only one more first-team appearance for United, joining Huddersfield later that year and playing over 250 games for the club. He embarked on a nomadic managerial career after retiring as a player in 1968 and died in 2002, aged 71.

Media

Ted Ellyard

Newspaper:

Photographer for Daily Mail

Peter Howard

Newspaper:

Telegraphist for Daily Mail

Others

Vera Lukic

Wife of a Yugoslav diplomat

(Graphics: Drew Jordan and John Bradford/The Athletic; Illustration: Eamonn Dalton/The Athletic; Photography: OFF/AFP, ullstein bild, Mirrorpix via Getty Images)

Read the full article here