It is 66 years since the Munich air disaster robbed English football of one of its greatest young teams.

Eight Manchester United players from Sir Matt Busby’s brilliant side were killed when the plane carrying them crashed on February 6, 1958, and two more were so badly injured they never played again. Fifteen others aboard also died.

To mark the anniversary and as a tribute to those who were lost, The Athletic has produced a special series of pieces. Read the others here:

There is a story that is always worth retelling when the conversation turns to the Munich air disaster, its significance to the modern Manchester United and one scene that says a lot about Wayne Rooney, favourably, and Cristiano Ronaldo, less so.

It goes back to the early part of 2008, in an upstairs room at United’s training ground, when five elderly men in smart blazers had been invited to talk through the horrors of February 6, 1958, with an audience of broadcast and newspaper journalists.

Sir Bobby Charlton – straight-backed, polite smile, unmistakable sadness in those rheumy eyes – was trembling as he took his seat. Bill Foulkes had taken only a couple of questions before he, too, had to steady himself and reach for a glass of water. Albert Scanlon, Harry Gregg and Kenny Morgans had their own stories, their own grief, about the harrowing sequence of events that left eight of their team-mates among the 23 dead in Munich.

We had gathered at the training ground because we were approaching the 50th anniversary of the disaster. The club had put on a media day and Wayne Rooney had been asked if he, as one of United’s A-listers, would join these proud old men and talk about what it meant to his generation.

He had said yes, even though he knew he was stepping out of his comfort zone, and you could forgive him for looking slightly nervous when it was such a difficult, emotive subject.

And respect was due: he had done his research. Rooney had made it his business to read up about Matt Busby’s team. The previous night, he had watched a DVD to learn about the events in Munich: the two aborted take-offs, the doomed third attempt, the devastating consequences for the ‘Busby Babes’.

Harry Gregg at the service to mark the 50th anniversary of the Munich air disaster in 2008 (John Peters/Manchester United via Getty Images)

He spoke respectfully, with tact and feeling, and in those moments you were reminded that Rooney, despite his occasional flaws, was a football man down to his bones.

But then Ronaldo came through the doors and started berating Karen Shotbolt, the club’s press officer. The event had overrun and Ronaldo seemed to be saying he was waiting for a lift from Rooney. He was tapping his watch, waving his hands in a show of over-the-top outrage, letting it be known that the great Cristiano should not be delayed for anyone.

Rooney was professional enough to continue with his interviews, but the attention was no longer exclusively on him. Ronaldo flounced out, cursing loudly, then reappeared 30 seconds later on the other side of the door. He started rapping his finger against the glass in the door, urging Rooney to hurry up. Then he opened it by a fraction and started to whistle at his team-mate, in the same way you might find a farmer trying to get the attention of his sheepdog.

What Ronaldo, then 22, failed to understand that day was the significance of Munich as the most important and tragic event in the club’s history. Maybe he would just say he did not realise what exactly it was he was interrupting, but it was tempting, nonetheless, to wonder whether it got back to Sir Alex Ferguson, a devoted student of United’s history, and what the manager would have made of it.

Today, it is exactly 66 years since the Elizabethan aircraft carrying Busby’s team crashed off the slush-filled runway at Munich-Riem airport, having stopped for refuelling on the way back from a European Cup quarter-final against Red Star Belgrade in the old Yugoslavia (now Serbia).

The Munich clock at Old Trafford (Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

A clock outside Old Trafford is permanently stopped at 3.04pm and, as happens on every anniversary, there will be a gathering beneath the stadium’s Munich plaque to lay wreaths, read the names of everyone who died and sing The Flowers of Manchester.

One cold and bitter Thursday in Munich, Germany

Eight great football stalwarts conceded victory

Eight men who will never play again met destruction there

The flowers of English football, the flowers of Manchester.

On Sunday, before Erik ten Hag’s team played West Ham, there was another fan-led service close to the Munich Tunnel, a walk-through that has been designed, museum-style, to tell the story of the tragedy. The flags of Old Trafford were half-mast and fans stood in silence to remember Eddie Colman, David Pegg, Roger Byrne, Geoff Bent, Mark Jones, Tommy Taylor, Liam Whelan and Duncan Edwards, as well as the 15 other people who died, including club secretary Walter Crickmer, chief coach Bert Whalley and trainer Tom Curry.

United fans unveil a banner in memory of players killed at Munich before Sunday’s game against West Ham (Michael Regan/Getty Images)

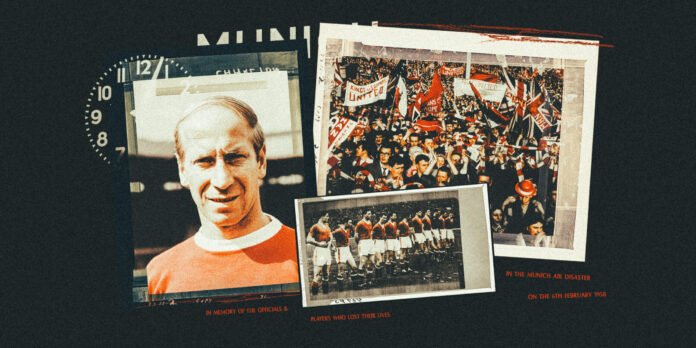

It has become an annual scene at Old Trafford before the closest game in United’s fixture list to the anniversary. This year, however, everything felt particularly poignant given that Bobby Charlton’s death last October, aged 86, made it the first service when none of the players who survived the crash was still alive.

Charlton was 20 at the time and, at that stage of his life, he was very much just one of the boys. His brother, Jack, used to say Bobby ”stopped smiling” after Munich and that he left his sparkle in the wreckage of the Elizabethan. And, speaking to Bobby at that media day in 2008, it was apparent he could still vividly remember the aborted takeoffs, the awful noise of metal on metal, then the smoke and grit and the blare of sirens.

“Everyone was so happy,” he said. “When we got on the plane there was so much laughter, but then the plane just went straight along the runway. You have a general idea how long it takes to take off and I was thinking, ‘There’s something not quite right here’. There were six or seven inches of slush on the runway. I bent my head down and braced myself. We went through the perimeter fence and hit a house. After that, there’s a void.”

Charlton went on to win the 1966 World Cup with England and, in the same year, the Ballon d’Or. He was part of the rebuilt United side that won the 1968 European Cup and, before Rooney caught and overhauled him, he had four decades as the leading all-time scorer for both club and country. To many, he is the greatest English footballer there has ever been, immortalised in a statue outside Old Trafford alongside George Best and Denis Law.

Yet he also spent many years haunted by the memories of regaining consciousness in the Munich snow, still strapped into his seat, and the morning in hospital when a German in the next bed read out the names of the dead. “The names of all my pals,” he said. “Friends I would go to the dance with at the weekend. Friends who would invite me to dinner at Christmas. It felt like my life was being taken away from me, piece by piece.”

Bobby Charlton recovering in a Munich hospital (Express Newspapers/Getty Images)

The legacy for United can be measured in many ways. There had been other football disasters before Munich, when the relevant clubs had suffered grievously. Never before, though, had a tragedy of this magnitude involved players. And not just ordinary players, but superstars-in-the-making, so young and full of potential the grief and loss resonated far beyond their sport.

“Everyone thought they knew the Babes,” Jim White, the United fan and author, wrote in Manchester United, The Biography. “Every kid who tore a colour picture of Duncan Edwards or Eddie Colman from their Football Monthly and put it on their bedroom wall felt the loss. It was a shared grief, a public grief.”

As the Manchester News Chronicle put it the day after the crash: “It is as if every family had lost a personal friend. Manchester United had become more than just a football team. To the man in the street, they were a symbol of how British sportsmanship, good honest Lancashire endeavour and the boy next door could reach the top.”

For the players who lost their lives, their reputation was forever secured. They died young and carefree and that alone created a hugely powerful legacy. Then add in the story of United’s almost implausible comeback, culminating in Busby collecting the 1968 European Cup, amid all his own grief, anguish and frequent guilt, and it becomes easier to understand why visitors to Old Trafford come from all over the planet, from Wythenshawe to Wagga Wagga, Beswick to Beijing, Collyhurst to Cairo.

In his autobiography, Charlton put it this way: “Before Munich, United were seen as Manchester’s club. Afterwards, everyone felt as if they owned a little bit.”

Does the younger generation understand? That is not always fully clear when, unless you are 60 or older, the likelihood is you will never have seen any of Busby’s teams. To remember the players who lost their lives in Munich, you would need to be 75 or above. The years roll on. Yet there is no shortage of people who are determined to make sure the history is passed from generation to generation.

“Walk through the Munich Tunnel on a matchday and you will see adults pointing out the players on the walls to youngsters,” says Iain McCartney, the United fan, historian and author. “Those adults might have been too young to have seen the Babes in the flesh, but Munich is a huge part of United’s history and will never be forgotten.”

McCartney runs the Manchester United Graves Society, which has a database of more than 600 players and coaches and helps to log and preserve their burial sites. He has written more than 20 books on United’s history and, like many supporters of his generation, his love for the club has, at the heart of it, the Busby Babes.

“It is, however, difficult to keep those memories alive,” he says. “Let’s say I wrote a book on Eddie Colman or David Pegg and you wrote one on Marcus Rashford. Yours would sell many more copies than mine simply because he is in the public eye, whereas I can guarantee there is a huge percentage who go to Old Trafford on a matchday who have never heard of Colman or Pegg.”

Overall, though, the numbers have grown considerably since the fan-led services began at the start of the century. Some walk past without realising what it is for. Most do, though, and the singing of Flowers of Manchester has become a tradition since a United supporter by the name of Gez Mason started it, alone, in one service. Mason was so keen to spread the word he printed out a sheet of paper, showing the date and time and an announcement of: “Singing The Flowers Here,” then stuck it to the brickwork of Old Trafford, close to the Munich plaque. Twenty-odd years later, it is difficult to imagine there will ever be an anniversary when that melancholic song is not heard.

“The Munich generation is coming to an end,” McCartney notes, “but it is hoped the story will continue to be held in the esteem that it deserves. The story of what happened, and how it happened, will always be there.”

That story involves the Manchester Munich Memorial Foundation (MMMF) arranging an outdoor service in Munich on every anniversary for fans to pay respects at Manchesterplatz (renamed by the German authorities in 2008), where there is a memorial listing the names of the 23 people who lost their lives.

The Munich air disaster memorial near where the accident took place (Johannes Simon/Getty Images)

“We have members who have been going to Munich for over 25 years,” says Ifty Ahmed, chairman of MMMF, which was founded in 2018. “It’s a pilgrimage to pay our respects, not just to the eight players and three members of staff who died, but everyone who lost their lives.

“It started as a few people going, then it was dozens and then hundreds. For the 60th anniversary, there were a few thousand. We’ve had Karl-Heinz Rummenigge and Uli Hoeness at services, representing Bayern Munich, as well as the Lord Mayor of Munich. I remember Rummenigge standing there once, looking out at these thousands of people, and saying, ‘Every time, the support never ceases to amaze me’.”

The MMMF is assisted with its arrangements by a group of Bayern Munich fans – the Red Docs of Germany – who also have an allegiance with the 20-time champions of England and take their name from Tommy ‘the Doc’ Docherty’s time as United manager in the 1970s.

Brian Kidd, a former Busby Babe and scorer in the 1968 European Cup final, is the foundation’s president. Bryan Robson, Andy Cole and Denis Irwin are among the former players who have attended services. Mike Phelan will represent the club this year.

Brian Kidd celebrates his goal in the 1968 European Cup final (Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

“You would probably describe us as old-school Reds,” Ahmed, 63, says of MMMF. “We love United and we love the Busby Babes but, more than anything, we want the younger generation to know the story. We don’t want the Babes ever to be forgotten. We want to preserve and enhance their legacy and we want the younger generation to pass it on to their children, too.”

Other events take place throughout the year. Mike Thomas and Elaine Giles, founders of the Munich58 group and organisers of the Old Trafford remembrance events, visit schools. Two weekends ago, United’s under-13s were given a talk about Munich by the United fan and author Roy Cavanagh, accompanied by Ahmed and Jimmy Murphy Junior, the son of Busby’s former assistant.

McCartney, meanwhile, has been prominently involved in arranging for Byrne, United’s captain, to have a memorial plaque. And, looking back, it is easy to understand why Walter Winterbottom, then the England manager, always said it should be remembered as a tragedy for the national team, too.

Byrne, a left-back, had represented England 33 times. Edwards had been an international since the age of 18. Charlton made the first of his 106 England appearances in April 1958, barely two months after being released from hospital. Taylor had won 19 caps and scored 16 goals, including two against France in England’s last international, pre-Munich, in November 1957. Pegg, tipped to replace the great Tom Finney, had made his England debut aged 21.

Mourners gather for Roger Byrne’s funeral in Manchester (PA Images via Getty Images)

Winterbottom was always convinced that England had the team to win the World Cup in 1958 and might have done so without the tragedy that had devastated the best team in the country.

“Had it been some lesser team, it would still have been a terrible tragedy,” says McCartney. “But here was a football club that had won the First Division championship two seasons in a row and been denied a league and FA Cup double (in 1957) through injury to Ray Wood, United’s goalkeeper, in the Wembley final.

“It was a United side that had just reached the European Cup semi-finals. It was a team on the crest of the wave. They were, indeed, the cream of the crop. Who knows what they would have achieved had the Flowers of Manchester been allowed to blossom?”

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here