It is 66 years since the Munich air disaster robbed English football of one of its greatest young teams.

Eight Manchester United players from Sir Matt Busby’s brilliant side were killed when the plane carrying them crashed on February 6, 1958, and two more were so badly injured they never played again. Fifteen others aboard also died.

To mark the anniversary and as a tribute to those who were lost, The Athletic has produced a special series of pieces. Read the others here:

In the offices of St Michael’s church, Warfield, there are blank looks. No, they say, they cannot remember anyone asking before. The name doesn’t immediately ring a bell, but they have a list. They have a grid system and, though it is a big old graveyard, that gives them a rough idea of where to look.

Through the black ornate gates, down the path, the gravestone is tucked away to the left. There is nothing showy about it, no clues on the epitaph. Nobody outside a very small circle would know about its relevance to Manchester United and, tragically, the Munich air disaster.

The grave of James Thain and his wife, Ruby (Daniel Taylor/The Athletic)

James Thain was the pilot who crashed the doomed Elizabethan flight off the slush-covered runway of Munich airport on February 6, 1958, with the loss of 23 lives, including eight players from Matt Busby’s team.

Thain made it out of the wreckage and returned to Warfield, in rural Berkshire, to run a poultry farm with his wife, Ruby, while suffering the added ordeal of being blamed for the tragedy. It took him 11 years and four inquiries — two German, two British — to clear his name and, in his fight for justice, he had to contend with the British government being reluctant to support him for fear of damaging Anglo-German relations.

Even after he was officially exonerated, the German authorities refused to accept — and still refuse to this day — the findings of the fourth tribunal, the Fay Commission, that their inquiries had come to the wrong conclusion. Thain’s supporters called it a scandal, one whose consequences led to him losing his house, his livelihood and, finally, his health. His family have always believed the enormous strain he was placed under contributed to his sudden death, aged 54, in 1975.

“He died relatively young and carried the weight of the crash on his shoulders for many, many years,” says Martin Thain, who is related to James and whose surname is still prevalent in the area. “I’m sure the trauma of such an awful accident was hugely impactful on its own, without the additional weight of suspicions and accusations that he was personally responsible for the crash.”

Martin was born in the years after Thain’s death and, as such, never had the chance to discuss it with the man himself. It is important, he says, to make it clear he is only a distant relative. He has, however, looked into the family’s history and it grieves him to see how Thain and his loved ones were made to suffer.

“The Scapegoat” was the title of the relevant chapter in Stephen Morrin’s 2007 book, The Munich Air Disaster, concluding that Thain had played a heroic part in the rescue operation.

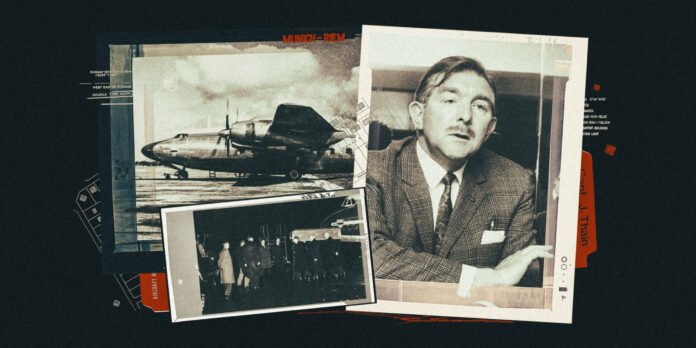

James Thain at home in Berkshire in 1960 (Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Harry Gregg, one of the survivors, was even more forthright in the years after Thain’s death. Gregg was the goalkeeper who had ignored Thain’s shouts to run to safety and helped him pull bodies from the wreckage. It was, said Gregg, a “conviction of convenience” to blame the pilot and that it was “time the real culprits, the men in the shadows, were finally dragged out to face the consequences”.

As it was, the finger of suspicion was pointed at Thain within hours of the crash, when the German authorities announced it had been caused by ice on the aircraft’s wings. The German Court of Inquiry made it official in March 1959, meaning the media were free to report that the deaths of 23 people rested squarely on Thain’s shoulders as the individual with the responsibility to make sure the plane was safe to take off.

“It’s positive that the UK government eventually intervened and helped to clear his name,” says Martin. “But you have to think: why didn’t they do so sooner?

“Were they scared of upsetting the German authorities? If so, why should a pilot and his family suffer the consequences of political manoeuvring? I am unsure whether the German authorities have even acknowledged or accepted the inquiry, but they should do, even now.”

Thain began his career as a sergeant in the Royal Air Force (RAF), serving in the Second World War, and worked his way up to become a flight lieutenant before leaving the RAF to join British European Airways (BEA) as a commercial pilot. On that fateful afternoon, he had landed the plane in Munich for refuelling, flying back from United’s European Cup quarter-final against Red Star Belgrade in the old Yugoslavia. The next day was his 37th birthday.

Thain’s belief was always that it was a build-up of slush, in heavy snow, that had caused the plane to lose speed and crash off the runway on its third attempted take-off. However, his argument was hard to prove in 1958 and for some years afterwards. Little was known at that time about the effects of slush on a plane’s take-off.

Officials inspect the wreckage at Munich (Keystone/Getty Images)

It was not until June 1969 that he was exonerated, aged 48. Until that point, he and his supporters had justifiable reasons to think they were the victims of not only a miscarriage of justice but also something more sinister.

Some years later, classified documents were released into the mainstream, showing how Foreign Office staff worried that the Fay Commission, led by Edgar Fay QC, would “cast doubt on the propriety of the original investigation” and there would be “a risk of serious damage to our relations with the Germans”.

At a secret meeting of ministers in April 1969, the Attorney General, Elwyn Jones, warned that “a report which made an attack on the German inquiry would be an unhappy outcome”. Lord Chalfont, the Foreign Secretary, reasoned that “we could not connive at the suppression of evidence even if it meant some damage to our relations with (former capital of West Germany) Bonn”.

It had cost Thain his flying licence. He lost his job with BEA (he received notification of his dismissal on Christmas morning, 1960). Even when he was officially cleared of any wrongdoing, he was never reinstated. Many days were spent on his remote farm listening to the overhead hum of aircraft flying to and from Heathrow and thinking that it should be him in the air. “If the crash didn’t kill you, the inquiry will,” one acquaintance from the British Airline Pilots’ Association told him.

His ordeal ran parallel with all the horrors he had already experienced on Flight 609, including the death of his co-pilot, friend and near-neighbour Ken Rayment, aged 37.

Thain and his family received hate mail and death threats. His daughter, Sebuda, who was seven at the time of the tragedy, was bullied at school.

“He believed he was the victim of a great injustice,” she said in 2008, attending a 50th-anniversary service in Manchester. “He was bitter and who can blame him? The British authorities cleared my father of all blame. That brought him a certain amount of relief but, in his heart of hearts, he knew the Germans still blamed him and that was not right.”

James Thain at a press conference after the UK government cleared him of responsibility for the Munich air disaster in 1969 (Wesley/Keystone/Getty Images)

Above all, Thain harboured immense bitterness towards one man — Hans Reichel, the chief accident investigator, who he suspected knew all along that ice on the wings had not caused the crash.

Thain kept in touch with Rayment’s widow, Mary, but learned at one point that her son, Steve, harboured a deep resentment towards him. Steve eventually became a pilot in his own right. Thain invited him to his farmhouse to present his side of the story and explain what he could about the reasons for the crash. It ended cordially and the two men remained in contact over the following years.

For Thain, however, there was also a financial impact that came with unemployment and the years of struggle that, at one point, led him and his supporters to send a portfolio of evidence to every MP and newspaper editor in the country.

Two years before his death, Thain had to give up Hayley Green Farm, his moated 15th-century property, to save his family from bankruptcy. Aged 52, he built a bungalow to accommodate them at the front of the land. He started dabbling in property development. His wife, Ruby, a teacher, abandoned plans for early retirement.

“It changed our whole pattern of life,” she said in 1975, for John Roberts’ book The Team That Wouldn’t Die. “Even all the work we did on the farm came to nothing in the end. By now, we would have been in a position to retire and enjoy what was left in our lives.”

Her husband died from heart failure a few months later and, to the wider world, the death notice in Flight International magazine largely went unnoticed. Ruby, who was seven years older, lived until 85 and was buried alongside him in St Michael’s church.

James Thain with his wife, Ruby, in 1960 (V Wright/Central Press/Getty Images)

Twenty-five years since Ruby’s death, the Thain family and collateral descendants are keen for the truth to be known. It is “for his legacy”, says Martin, who hopes “new generations can understand the full story, how he had to fight to clear his name, and how he finally achieved it”.

Sebuda’s invitation to the 50th-anniversary commemorations at Old Trafford was gratefully received as confirmation that, inside United, they see her father as another victim of the tragedy, not its cause.

In Manchester, it has never been the priority to apportion blame. There is also an acceptance that, despite the treacherous weather in Munich, United’s travelling party were under pressure to get back for their game against Wolverhampton Wanderers two days later. Busby had gone against the wishes of the Football League to take his team into Europe and, against that backdrop, nobody wanted to risk getting stuck in Munich.

“James Thain was an easy target,” says the historian and author Iain McCartney, whose library of work makes him arguably the most prolific writer of United history books in the industry. “He was a scapegoat. I feel sorry for him and his family.

“It is hard to say, but if only Matt Busby, or some of the players, had stood up and said, ‘We’re not flying’. But having ignored the Football League and ventured into the European Cup in the first place, Busby did not want to risk stopping in Munich for the night, or perhaps even the following day, getting back into Manchester late, or not at all, forcing the postponement of the home fixture against Wolves.

“Thain was given the OK (to take off). He tried but failed and suffered for that. But it wasn’t his fault and I have never heard him blamed for what occurred that Thursday afternoon.”

Stanley Williamson’s book, Captain Thain’s Ordeal, tells the story in more forensic detail, written with the approval and cooperation of the man who had been accused, scapegoated and, for the most part, abandoned. And it is a powerful read from the very first line. “The Munich air disaster began as a national tragedy and developed into an international scandal,” writes the author.

Yet that book came out in 1972 on a smallish print run and it is rare – and expensive – to find a copy these days. Otherwise, you will not read much about Thain’s life story in the acres of print devoted to Munich.

Few remember he took a fire extinguisher to douse several fires burning around the mangled wreckage of the Elizabethan. It is rarely mentioned that Thain, dazed and profoundly shocked, still had the clarity of mind to use an axe to free the unconscious Rayment, whose legs were trapped in the tangled metal of the cockpit.

Survivors leave Munich in 1958 – James Thain is at the top of the stairs, wireless operator George W Rogers in the light jacket, along with stewardesses Rosemary Cheverton and Margaret Bellis (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Nor is the story often told about a series of official inquiries that, in the words of Williamson, make for “shameful reading” for the people in high positions who tried to pin everything on Thain.

Sebuda’s memories included realising, at a young age, that people outside the family often had a certain perception of her father. “I remember all the reporters coming to the house and the other children at school talking about how life was for them. I would just say, ‘Oh, our life was different’.”

By the time her father was cleared, however, the news agenda had moved on. Busby had just retired. United had been rebuilt, winning the 1968 European Cup. In the days before the internet and rolling news channels, the coverage in the London Evening Standard newspaper told its own story. The headline — “Munich Crash Pilot Cleared” — was given 11 paragraphs in a slot on page 21, halfway down the page.

Thain deserved more credit. His theory that slush was to blame was strengthened by the findings of a near-crash in Vancouver in the winter of 1948-49 when the pilot of a Canadair North Star found it impossible, in similar weather, to lift it off the runway.

Thain’s refusal to give up his fight for justice pushed the aviation authorities into undertaking more research. Nobody can say for sure, but the increase in knowledge has quite conceivably prevented another Munich.

“Twenty-three people lost their lives,” writes Williamson, in the final paragraph of Captain Thain’s Ordeal. “But for James Thain, there would have been a 24th victim — the truth. She is still limping a little, but he has at least brought her out alive. We should be grateful to him.”

(Top photos: Wesley/Keystone/Getty Images; PA Images via Getty Images; Mirrorpix via Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here