After 31 days of pushing broccoli and pieces of steamed cod around their plates, transfer fans finally got the deadline-day feast they were craving on Thursday: Lewis Hamilton to Ferrari, here we go #boom.

Thank heavens for the unbridled dream-weavers of Formula 1, hey? None of that lily-livered, anti-competitive, financial fair play nonsense there.

But if your palate is restricted to football transfers, the January window has been a month of baked potatoes. And everybody seems to know whose fault it is: FFFP (and yes, the extra F is intentional, but we are not spelling it out).

“In an ideal world, given the freedom to act, we would have brought players in already,” said Newcastle manager Eddie Howe when asked about signings last week. “But we’re not in that situation… financial fair play is a problem for us and we’re having to navigate around that.”

“Of course, there is a little bit of frustration there. I think there are lots of managers at different clubs that would attest to that,” said Ipswich Town’s Kieran McKenna when asked the same question.

“I looked but there is no space,” explained Manchester United boss Erik ten Hag when the query came his way. “There is no space for FFP to do something about this lack of quantity in the striker position.”

Ten Hag said FFP stopped United from making signings, but is he right? (Matthew Peters/Manchester United via Getty Images)

West Ham’s David Moyes summed it up like this: “The fact of the matter is football in general has cut everybody’s legs off a little bit — we’re all a bit less because of FFP.”

No freedom, widespread frustration, claustrophobia, missing body parts… this is professional football we’re talking about and not the latest, binge-fest dystopia in the streaming charts, right?

At times this month, it has been hard to tell.

For example, The Athletic sent a message to a Premier League club exec to see if there was any truth to the rumour that Chelsea’s Trevoh Chalobah could be moving to Nottingham Forest, a club that tried to sign him in the summer.

“Impossible,” came the off-the-record response. “FFP destroying the game.”

Now, while it is a shame the 24-year-old defender may not be able to join a club that might actually play him, is the unlikelihood of that move evidence that an attempt to curb how much money clubs lose is “destroying the game”?

Maybe. Or perhaps this is just a case of a hot prospect not quite blossoming into the top-level player his club hoped for but that club maintaining an unrealistic valuation of the player.

Injuries have not helped and Chalobah is still young enough to prove them wrong, but should we not be more concerned that Chelsea have spent more than £1billion on new players in the past 18 months and got worse? Or that Forest have signed more than 40 players in the same period, including seven in his position?

They seem to be issues we should focus on rather than worry too much about some clubs being unable to bring in another club’s cast-offs halfway through the season because they have either breached the threshold for permitted losses or are in danger of doing so.

This will all seem very odd to fans of teams below the Championship, where deadline days come and go without much fuss and nobody is taking a loan with an obligation to buy, or those followers of the game who believe this week’s big news was Liverpool blitzing Chelsea, Erling Haaland’s return, Luton getting out of the relegation zone, James Maddison versus Neal Maupay… you know, the actual games.

Let’s park that thought for a while and get back to the discourse du jour: FFP ruining the January window.

“It’s one factor among many, as opposed to the only reason,” says Tim Bridge, the lead partner in Deloitte’s Sports Business Group. And he should know: his firm audits the Premier League itself as well as several leading clubs.

So, let’s explore those non-FFP factors.

It’s January, what do you expect?

The window is still slightly ajar as I type this sentence and Premier League clubs have spent about £100million on transfer and loan fees so far this month, with the biggest single signing being Tottenham’s Radu Dragusin, the versatile Romanian defender they bought from Genoa for £25million.

This is one-eighth of the amount the clubs spent last January, so it is easy to see why people believe this window has been a buzzkill, but there are a few points to make about the gap between those numbers.

Dragusin is the biggest signing of the window (Marc Atkins/Getty Images)

Last year’s spend was, to put it mildly, unusual.

The average January spend for the entire Premier League over the past decade has been more like £200million, but Chelsea spent almost that much on Enzo Fernandez and Mykhailo Mudryk, with six more signings on top. They accounted for more than a third of the £815million total themselves.

The clubs have already, for what it is worth, spent more than they did in 2021, although the big bad acronym then was COVID.

No Boehly, no party

Chelsea’s big spend last January was sandwiched between similarly extravagant outlays in the summers of 2022 and 2023. There are several reasons for this.

The first is to do with how transfers are accounted for by clubs, with the key term being amortisation, which is like depreciation but for intangible assets, not tangible ones like buildings or cars.

When clubs buy a player for £50million and give them a five-year contract, the fee is amortised in annual £10million chunks over the length of that contract. This makes sense when you remember that, once out of contract, players are free agents and therefore have no value to their recent employer. That £10million amortisation cost is what shows up in the club’s annual FFP submissions.

What Chelsea’s new owners, American investor Todd Boehly and the U.S.-based private equity firm Clearlake, worked out was that if you give players unusually long contracts — eight years, for instance — you stretch the initial cost over a longer period.

Boehly and Chelsea have been much more restrained this January (Alex Pantling/Getty Images)

Very clever! Well, we shall see. Or maybe not, because first UEFA and then the Premier League decided this was a piece of accounting trickery they didn’t want to encourage, so they changed their rules so clubs can only amortise fees for a maximum of five years. Loophole closed.

The second reason behind Chelsea’s 18-month shopping spree is the fact that they, more than any other club, although a few are going the same way, have taken the view that academies are for producing transfer vouchers, not first-team players.

This is an unfortunate consequence of the current FFP regime and it is connected to the point about amortisation. When a club sells a player, they get the full benefit of the fee immediately from an FFP point of view, even if they nearly always take payment in instalments, which is another point we shall return to.

But if you are selling a player you bought in, your player-trading profit is the fee received minus whatever unamortised value he had on your balance sheet. If we go back to the example of the £50million signing, if you sell him for £30million two years later, there is no profit, as his book value is £30million. Sell him for the same price a year later and you make a profit of £10million.

That’s nice, but it’s not as nice as the £30million profit you would make if that player had come through your academy and had no unamortised value on your balance sheet. Homegrown players are pure FFP profit.

And this brings us back to Chalobah, although we could also talk about Armando Broja, another FFP chip Chelsea put in the shop window this month (he went on loan to Fulham), or Conor Gallagher, who has arguably been their player of the season but looks destined to leave this summer simply to balance the books.

To be fair to Chelsea, they have been doing this for a while. They are good at producing players, they usually get decent money for them and they have won lots of trophies over the past 20 years, so this strategy is supported by more evidence than the amortisation trick.

But when the players you are trying to flog are lower-half-of-the-table talents at top-half prices, the business model gets bunged up, which means Chelsea cannot spend, which means other clubs cannot spend Chelsea’s money either. This is called a lack of liquidity.

Don’t worry, Chelsea will sell Broja, Chalobah and Gallagher at some point soon — the writing on the wall cannot be erased — and the cycle will resume.

A Saudi siesta

Speaking of liquidity, the biggest pump-primer in 2023 was Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund.

The tsunami of Saudi sovereign wealth did not really hit European football until last summer when PIF and other state-linked enterprises took control of the eight biggest teams in the Saudi Pro League and started filling them with players bought from European teams.

Cristiano Ronaldo was the only big name to make the move last winter but Premier League clubs had already realised a new whale had arrived. This high roller would hit almost every table, in every casino, over the summer, leaving a trail of cash in their wake.

Ronaldo moved to Saudi last January but business has been quiet this winter (Yasser Bakhsh/Getty Images)

Unfortunately, the whale appears to prefer warmer waters and has not been spotted in Europe this winter. It’s OK, though, they will be back this summer and, to mix our sea-creature metaphors, European clubs are going to need bigger boats to keep up.

Once upon a time, of course, Premier League clubs might have funded their spending money by selling a player or two to an Italian or Spanish giant, or maybe the Chinese Super League. Sadly, those markets either did not bother opening up this winter or are shut permanently.

Empty shelves

That leads us nicely to a point that can be made about every January window: which players are available who will actually make a difference?

This point was well made in a piece by my colleague Nick Miller last week. He quoted a club executive who noted that “January is always a difficult buyers’ market” because “there’s only a small selection of teams to buy from and you’ll probably have to overpay”.

And an agent said: “If a player is available in January, he’s available for a reason.” He did not need to spell it out.

“We’ve done analysis that looks at net spend in January and how that correlates with changes in points-per-game after the window,” explained Omar Chaudhuri, chief intelligence officer for the sports consultancy Twenty First Group.

“If you look across the ‘big five’ European leagues over time, there is no correlation.”

According to a study from 2017, a net spend in January of about £25million might only be worth a maximum of two extra points over the rest of the season.

Two points, though… that could make the difference, right?

Yes, maybe, but that £25million in 2017 is going to be considerably more now and it still does not guarantee anything.

False memories

“Another interesting one,” added Chaudhuri, “is my colleague did some analysis that looked at strikers bought in January since 2012 and found that 40 per cent of them didn’t even score a goal in the remainder of that season.”

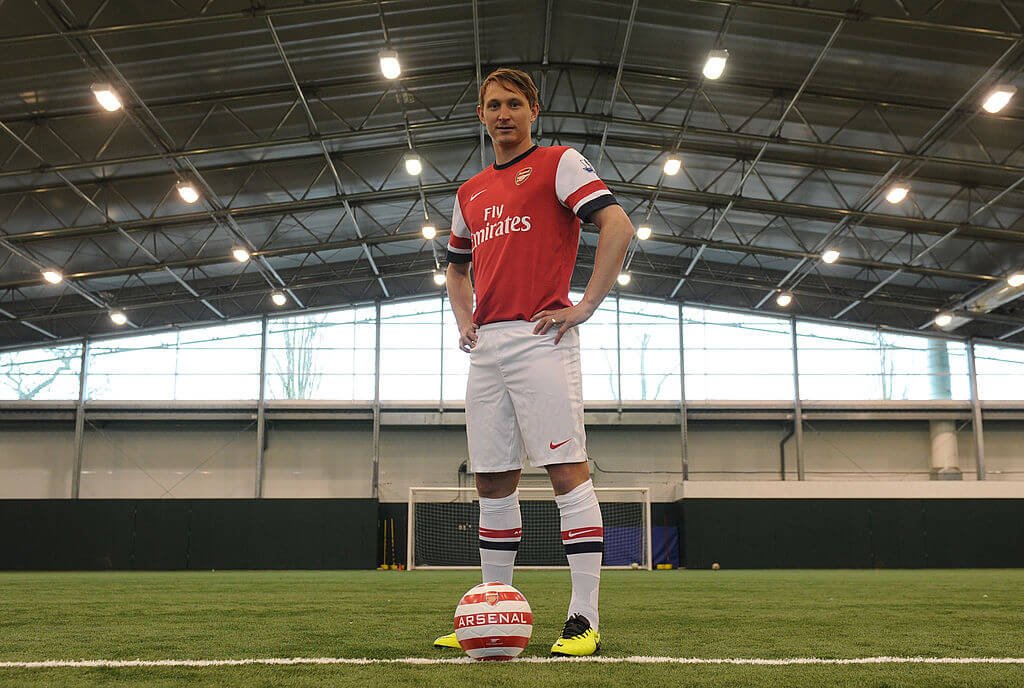

This illustrates the point that we tend to remember the hits more readily than the misses. For every Nemanja Vidic, Virgil van Dijk or Kieran Trippier (popular picks in rankings of top January signings), there are dozens of Alexis Sanchez-to-Manchester-Uniteds or Kim-Kallstrom-to-Arsenals. We lump these regular failures together and think they are balanced by the rare winter arrivals who do make a difference.

Kallstrom arrived injured (Stuart MacFarlane/Arsenal FC via Getty Images)

Is it not telling that the clubs currently first and second in the table, both of whom have plenty of FFP headroom, have not been part of the transfer window gossip in any meaningful way? Sure, Manchester City have spent north of £10million on Claudio Echeverri, but they have loaned the 18-year-old Argentine back to River Plate. He is one for tomorrow, not today.

In another piece on these pages last week, three of our Liverpool reporters were asked if the leaders should be looking to add anyone this window. They all said no. Who is out there better than the options they already have?

No jeopardy

Of course, teams at the top are rarely the ones who make the weather on deadline day, the action usually occurs at the other end of the table.

Last year, Leeds United, Leicester City and Southampton spent almost £140million between them, only to have worse points-per-game records after January than they did before Christmas. All three were relegated.

Now, whether it is a lack of decent players, a realisation that spending big in January is a Hail Mary or FFP handcuffs, the usual suspects have not gone wild in the aisles this January.

Last-placed Sheffield United brought in former Blackburn Rovers striker Ben Brereton Diaz on loan and he has already scored a couple of goals: a marked improvement on his record for Villarreal, where he played 20 games this season without notching.

Is FFP the issue here or is it the fact Sheffield United almost ran out of money last year — triggering a bizarre takeover tango with a Nigerian businessman who is now facing fraud charges in the U.S. — and have been up for sale for at least two years?

Burnley, two points better off in 19th, have borrowed David Datro Fofana from Chelsea’s stockpile, but the 21-year-old only managed two goals in 17 games whilst on loan for Union Berlin, so he is hardly the proven gun-for-hire Burnley would appear to require.

Is FFP the problem or is it the fact Burnley’s owners borrowed large amounts of money to buy the club in 2020 and must run a tight ship to meet the interest payments?

Everton, sadly, have not and cannot bring anyone in.

Dyche has been unable to add to his squad (Mike Hewitt/Getty Images)

On the one hand, this is because they have already been docked 10 points for becoming the first team to breach the Premier League’s threshold for permitted losses for the rolling period to July 2022 and now face another punishment for doing it again in the period to July 2023, but it is also because they are being kept afloat by loans from an American private investment firm that is now 20 weeks into a 12-week takeover approval process.

Luton, who climbed above Everton this week and are 17th, one place above the drop zone, have loads of FFP headroom but have opted to sign only a couple of players on small fees, loaning one of them, Reading’s Tom Holmes, back to his former club. They appear to believe clever recruitment, good coaching and hard work is the way to go. And why not? It is the recipe that took them from bankruptcy and the fifth tier to the top flight in a decade.

Nottingham Forest are a point and a place better off but are in the same trouble as Everton, which suggests they are in danger of losing points, too.

With Sheffield United and Burnley nine and seven points, respectively, off safety and Everton and Forest at the mercy of an independent panel (two, in Everton’s case), have the perils of life in the lower half of the table been lifted slightly?

Brentford, Crystal Palace, Bournemouth and Fulham, the teams in the four places above the bottom five, all with wealthy owners, have largely kept their wallets in their pockets.

Brentford added Tottenham full-back Sergio Reguilon on loan, while Palace have signed Colombian full-back Daniel Munoz and Adam Wharton, a highly promising midfielder with a £22million price tag. They both look like decent signings but neither are the stuff of deadline-day legend — they are too… sensible.

Bournemouth and Fulham have stood pat, although the latter brought in Broja. There is always a Chelsea loan.

But the overwhelming impression is that these guys aren’t panicking enough. They clearly don’t think they need to.

FFP: the fall guy

So, if there are other reasons why clubs have not entertained us with their extravagant spending, is blaming FFP just an excuse?

Maybe — but let us acknowledge that for some, it is a genuine concern, and not just the obvious two.

For example, Bournemouth, Brentford, Burnley, Luton, Fulham, Nottingham Forest and Sheffield United have all spent time in the Championship over the past four seasons, so they have lower FFP thresholds than clubs that have been in the Premier League for the entirety of the relevant period. Top-flight clubs can lose £105million over a three-year period, which averages out to £35million a year. But the threshold is lower in the Championship, where clubs are only permitted to lose £13million. This is why Forest’s upper limit was £61million, two seasons of £13million and one of £35million.

The reference to four seasons, not three, was not a mistake. The EFL, Premier League and UEFA have treated the two Covid-hit seasons as one for FFP purposes. Almost every club in Europe made huge losses in 2019-20 and 2020-21, with an average of the two seasons’ results being the number that matters.

However, the two pandemic years will drop off the calculation this year, as the next submission will be for the 2021-22, 2022-23 and 2023-24 seasons.

You might think this should be good news for clubs as they get to lose a big loss from their total. For many of them, it is. But not all, as the leagues gave the clubs considerable leeway in terms of the losses they could claim were Covid’s fault. Next year’s FFP calculation might, counter-intuitively, be harder than this year’s because they lose that excuse.

But let’s return to clubs who appear to have blamed the regulations for their inaction in the market when there might be a more obvious reason. Foremost among these are Manchester United.

Speaking to fans before Christmas, director of football John Murtough said the club was “not expecting to be particularly busy” in January, apart, perhaps, from a few “deals around the edges of the squad”.

So far, so normal. But he then said: “We’ve seen this season that financial fair play rules have real teeth, so we have to be very careful to ensure we remain compliant and we will. But that means being really disciplined on spending going forward, with a balance between incomings and outgoings.”

I have already mentioned that Ten Hag has blamed FFP for their failure to find a striker to replace the injured Anthony Martial (a failure that feels at least three years old), but is it true?

Yes, Manchester United were fined €300,000 (£256,000) by UEFA last year, but that was for a “minor break-even deficit” that was partially caused by the pound’s weakness against the dollar. And UEFA’s “break-even” threshold for the period in question was £25million, not the Premier League’s generous £105million.

According to Swiss Ramble, the pre-eminent football finance blogger, United’s FFP calculation for 2023 was in the region of £16million in credit, which he believed gave them £31million in headroom.

But why only £31million if the loss threshold is £105million? Because the rules actually state you can only lose £5million a year, but it stretches to £35million if it is covered by £30million in “secure funding”, which cannot be debt.

Not unreasonably, Swiss Ramble has always assumed that Manchester United must stay within a three-year limit of £15million because their owners, the Glazer family, have never put any money into the club. On the contrary, they have distinguished themselves by taking money out in dividends.

However, when the club released its most recent set of accounts in January, it told reporters they were comfortably inside the FFP threshold because their £200m revolving credit facility, or overdraft, counts as “secure funding”. The Athletic asked the Premier League if this was right and the league nodded.

So, Manchester United actually had more than £120million in FFP this season. A cushion they will retain next season as new minority owner Sir Jim Ratcliffe is putting $300million (£235million) into the business this year. No space? How much do you need, Erik?

Maxed out

The real issue at Old Trafford, then, is not whether they are close to an arbitrary threshold set by the league, it is that they have reached their own very real limit. But they are not alone. Far from it.

Kieran Maguire, podcaster and football finance expert at the University of Liverpool, puts it like this: “There’s a belief amongst many fans that clubs should run at significant losses underwritten by owners. Chelsea cost Abramovich £900,000 a week for 19 years and this set a benchmark of entitled indulgence.

“But fans also ignore that clubs already owe in excess of £2billion in instalments for transfers made in previous windows.”

Yep, £2billion owed for players bought with IOUs. Manchester United top this particular debtors’ list with a staggering £364million still to pay on players they have bought. Tottenham’s figure is £252million, while Manchester City owe £204million, Arsenal £188million, Liverpool £172million and Chelsea £152million.

OK, every club is paying fees in instalments now, so United are owed about £60million in fees, but that is a net transfer debt of more than £300m.

And when you add this to the money the Glazers borrowed to buy the club in 2005 and then dumped on the club’s balance sheet, as well as the debts the club accrued during the pandemic, you get to a total debt of more than £1.1billion.

So we should pose the same question to United that we asked of Sheffield United and Burnley: is the real problem here the pesky league and its meddling rules or you realising you cannot go on like this?

This feels like a good place to stop, as we hope that anyone who has read this far has got the gist.

You will notice that this piece has not addressed whether FFP is particularly effective at promoting sustainability or encouraging a healthier competitive balance. The jury has been out on that one for a decade. In fact, we are worried they might have got lost.

We have also not mentioned the fact there are a couple of Premier League clubs who would like to spend more and their owners are good for it, but cannot because they are constrained by FFP. There are clearly questions to ask here about how “fair” financial fair play is, but the fact the leagues and UEFA dropped that name for their cost-control measures some years ago probably answers that.

And, of course, the Premier League is about to scrap its current FFP regime — the profitability and sustainability rules, to give them their real name — so we can have a proper debate about Newcastle United and Aston Villa then. We can also talk about Manchester City’s very particular FFP issues, too. OK?

(Top photo: Harriet Lander – Chelsea FC/Chelsea FC via Getty Images)

Read the full article here