Gael Clichy couldn’t believe his eyes.

“I could see four or five players playing with both feet, like Santi Cazorla. I’m like, ‘That’s not normal’.”

Clichy, who won the Premier League title with Arsenal and Manchester City and is now assistant coach with France Under-21s, shakes his head.

“We have one (two-footed) player with France Under-21s — (Rayan) Cherki, who plays for Lyon. That’s only the second player that I know who plays like this during all my career. So there’s Cherki, there’s Cazorla… and maybe (Ousmane) Dembele, who plays for Paris Saint-Germain now. And now, all of a sudden, I’m watching this team play, and they have four or five like this.”

That team was South Korea Under-21s, who defeated their French counterparts 3-0 in Le Havre in November.

(Jean Catuffe/Getty Images)

Clichy had watched South Korea’s previous five matches to prepare for that game and was so taken aback by what he saw that he is already making plans to visit the Asian country to learn more about how they develop two-footed players.

“I can’t stop thinking, what if you take four or five of my players from the French team, or the team I will have if I become a coach in five or six years, and you have the possibility to play them right, left and centre because they can play with both feet?”.

On the face of it, that doesn’t seem too much to ask. Yet two-footed players — genuinely two-footed ones (we’re talking Glenn Hoddle and Kenny Dalglish levels) — are something of an enigma.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the most two-footed goalscorer in Premier League history is also from South Korea. Son Heung-min has scored 46 Premier League goals with his ‘weaker’ left — five more than Harry Kane, in second place. Robin van Persie’s “chocolate leg” — that’s what the Dutchman called his right — is third.

Son Woong-jung, Son’s father and former coach, explained to The Athletic a couple of years ago how their training programme went way beyond practising shooting with both feet at a young age.

“In Heung-min’s case, I knew he was right-footed but I made sure that socks, cleats (football boots), shoes, trousers, watch or anything like that, he put on his left side first, so he never forgot about the two-footedness,” he said.

Son Heung-min’s father Son Woong-jun in South Korea (Charlie Eccleshare/The Athletic)

Clichy’s backstory is interesting too, bearing in mind he spent the vast majority of his career at left-back despite being naturally right-footed.

The seeds for that transition were sown at a young age, when Clichy’s father was his coach (there’s a theme developing here) and disallowed any goal that his son scored with his right. Naturally, that encouraged Clichy to improve his left foot. But by far the biggest factor in the development of his then weaker foot was the time that he spent striking a ball against a wall at the football academy he attended in Castelmaurou, in the south of France.

By the time Clichy joined Arsenal in 2003, at the age of 18, his dominant foot was his left and it was his right that needed to catch up. In fact, he had turned into a left-back — and that was why manager Arsene Wenger signed him.

Clichy crosses with his left for Arsenal (Mark Leech/Offside via Getty Images)

“If I’m being honest, I don’t think my dad thought, ‘He’s going to be a left-back’, or, ‘He’s gonna be playing professionally because of that (disallowing goals with his right)’. But I do believe if I was only a right-footed player, maybe the door for professional football would not have been open for me,” Clichy says.

Cazorla’s name often gets brought up on this topic and for good reason, given that the Spaniard was as close as you will get to an ambidextrous footballer in the modern era.

There is a clip of Cazorla preparing to take an outswinging corner for Arsenal at Watford with his right foot, only for his team-mate Laurent Koscielny to signal that he would like an inswinger instead. In normal circumstances, a different player would trot over to take the corner. Instead, Cazorla walks around the corner flag, readdresses the ball and delivers it left-footed.

The corner came to nothing, but the fact that the footage went viral says everything about how unusual it is to see a player confident enough to strike a dead ball with either foot.

Cazorla could deliver corners just as well with either foot (Stuart MacFarlane/Arsenal FC via Getty Images)

There was a similar fuss on social media when Ivan Perisic took inswinging corners with his left and right foot for Tottenham against Chelsea a couple of years ago.

Within the game, former Premier League players talk about the ability that John Terry had to hit diagonals with his left, how beautifully Tom Huddlestone could strike a ball with either foot, and the way Cristiano Ronaldo worked religiously at a young age to turn a potential weakness into a strength.

There will, of course, be other examples too — that Zinedine Zidane volley in the 2002 Champions League final said everything about the Frenchman’s technique with his weaker foot — but it’s not a long list by any stretch and, interestingly, there’s little to suggest (with apologies to Adam Lallana, in particular) that the generation behind them are markedly different.

On this day, 2002:

Zinedine Zidane scored *that* volley…

One of the greatest ever goals in a Champions League final 🙌 pic.twitter.com/XXowuodSBO

— Football on TNT Sports (@footballontnt) May 15, 2018

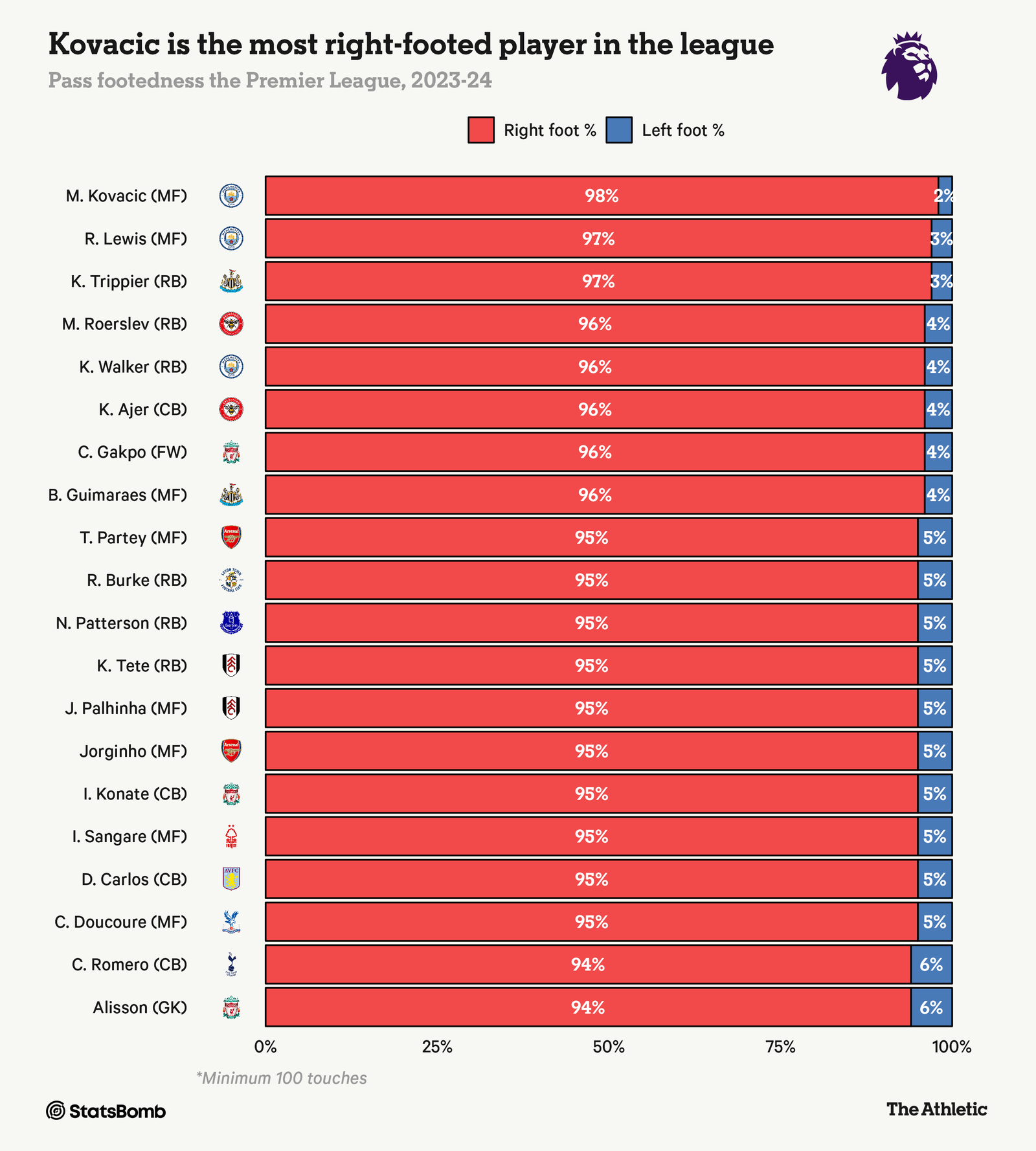

The StatsBomb data featured later in this article makes for fascinating reading and shows just how rarely some of the top Premier League players use their weaker foot to pass. Who would have thought, for example, that Mateo Kovacic, a central midfielder, averages only two passes out of every 100 with his left foot for Manchester City?

The data for a certain Brazilian winger at Manchester United is probably less surprising.

“If Antony got on a bike, he’d just cycle round in circles, wouldn’t he? Because his left leg is brilliant and his right leg is practically not there,” Steve Wilson, the BBC commentator, said during United’s 4-2 victory over Newport County in the FA Cup last month. Ironically, Antony went on to score with his right foot later in that game.

More commonly, television commentators say the opposite to Wilson and end up defending a player who squanders a chance by highlighting how it “was on their weaker foot” — a comment that leaves a lot of football fans scratching their heads.

Their argument is simple: How can a professional footballer, who is playing at the highest level and often getting paid millions to do so, be excused for a poor shot because it was on their weaker foot?

A quiz question for you to put to your friends: Only two players have scored both a right- and left-footed penalty in the Premier League. Who are they?

The answer is Obafemi Martins, the former Newcastle and Birmingham striker, and Bobby Zamora, who played in the Premier League for Tottenham, West Ham, Fulham and Queens Park Rangers.

Zamora laughs. “I only knew that (penalty stat) when I was at QPR, towards the end of my career in the Premier League,” he says. “I’d scored a couple of free kicks with my left foot and I could very easily have done it with my right foot too. I thought, ‘S**t, let me do that, because nobody is going to do that as well!’.”

Naturally left-footed, Zamora wasn’t showing off when he scored a penalty for Fulham against Newcastle with his right. Andreas Brehme famously, and remarkably, did something similar for West Germany against Argentina in the 1990 World Cup final, as did the USWNT player Brandi Chastain in their 1999 World Cup final against China — after being asked to do so by her coach to confuse the opposition goalkeeper.

For Zamora, who had already scored several outstanding goals for Fulham with his right foot, including a fantastic strike against Shakhtar Donetsk during their run to the Europa League final in 2010, his Newcastle penalty seemed perfectly “normal”.

Zamora is a member of a very exclusive Premier League club (Glyn Kirk/AFP via Getty Images)

“I think I’m naturally left-footed,” Zamora explains. “But all the kids when I grew up — I’m talking about aged five or six, in the street — seemed to be right-footed. I thought to myself, ‘I’m a bit weird. That’s not right.’ So I ended up playing with my right foot. And I suppose when you learn something when you’re young, it’s maybe a little easier. But by the age of 10 or 11, when I played in Sunday teams, I was just happy with both.”

In the case of Manchester City’s Kevin De Bruyne, who scored a hat-trick of goals with his ‘weaker’ foot against Wolves two years ago and is a superb striker of the ball with both, everything goes back to one of his friends’ parents scolding him for ruining their back garden when he was a child.

“I wasn’t allowed to shoot with my right, because I was killing all the flowers,” De Bruyne said. “They told me to shoot with my left, and I was really young, so I think I practised it a lot and it became more natural to shoot with either.”

There is some creative outside-the-box thinking going on elsewhere.

At AFC Wimbledon in League Two, English football’s fourth tier, academy players have to wear an odd sock on their weaker foot during training sessions and even in matches.

Wimbledon accept that by highlighting a player’s weaker foot it helps the opposition in games, but that in itself provides another incentive to practise, improve and work towards the ultimate reward: matching socks for anyone who becomes two-footed.

GOAL OF THE MONTH | November 2023

A: Oscar 😎

B: Joe 🔥

C: Fin 👌🏻

D: Stanley 👊🏽

E: Dan 😍

F: Harry 🥶It’s that time again… vote by leaving the letter of the goal you think is the best, in the comments below ⚽️ pic.twitter.com/ZfhjPGCRB4

— AFC Wimbledon Academy (@AFCWAcademy) December 6, 2023

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of developing both feet at the earliest opportunity.

“You have to start encouraging it at academy level and stimulate it from a young age, when the central nervous system is still developing,” Vitor Pereira, the former Fenerbahce coach who also worked in the academy at Porto, told The Athletic when discussing Arda Guler, a gifted Turkish teenager who signed for Real Madrid last year.

“It’s like learning to swim or ride a bike: it’s easy when we’re kids, because we assimilate everything easily and we have good coordination, but it’s much harder if you start after the age of 20.”

Some professional footballers try to play catch-up on their own time — and out of sight, too. As bizarre as this sounds, there are Premier League players who pay for one-to-one coaching in their back gardens, where they focus on improving their weaker foot without fear of anyone seeing their mistakes.

Ultimately, though, there is no shortcut to success, whether training in private or in public.

“You need to have a very resilient player, because it will take some work,” Clichy adds, reflecting on the difficulties he went through when trying to bring his right foot up to speed after he joined Arsenal. “Sometimes as a player, you also will feel ashamed of that, because you will see yourself struggle, you are exposed.”

Clichy remembers Arsenal team-mate Thierry Henry regularly taking him aside for weaker-foot practice after training, to work on striking the ball with their laces.

“I was like, ‘My right is not that good any more, I’m actually left-footed’,” Clichy recalls. “At the beginning, (shooting with) my right was like bananas, going this way and that way. But then, after a few weeks — because it goes quickly when you’re really into it — you grow in confidence.”

(Stuart MacFarlane/Arsenal FC via Getty Images)

Not everyone seems prepared to put in that time and effort, though. Some footballers will bend over backwards to get the ball onto their stronger foot.

“Even at the top level, you can see players who are so uncomfortable on their wrong foot that it’s comical,” Zamora says. “I’m talking about elite players, internationals — you put it onto their wrong foot and they’re like a fish up a tree.

“They can do certain things with their wrong foot, but it’s the consistency and the accuracy. For example, there are players who can hit a diagonal with their wrong foot — but it’s (just playing the ball) into an area. They wouldn’t be able to do what they can do with their stronger foot — (putting it) right onto someone’s toe.”

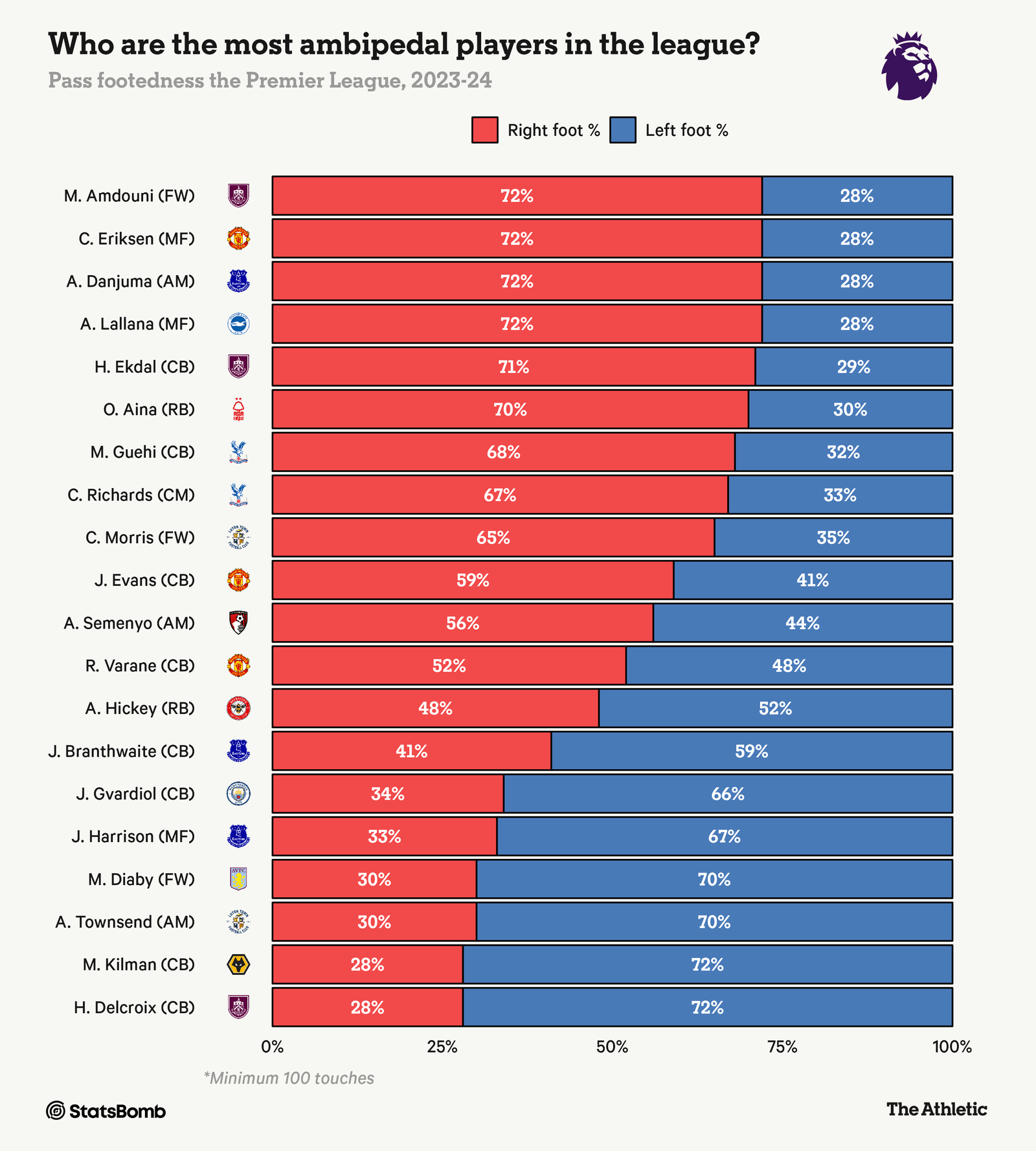

Raphael Varane and Aaron Hickey.

An unlikely duo. But, on paper, the most two-footed passers in the Premier League this season.

According to data provided by StatsBomb before last weekend’s round of matches, Manchester United’s Varane has played 52 per cent of passes with his right foot and 48 per cent with his left, and Brentford’s Hickey vice-versa, which puts them in the middle of the table below. The next most two-footed players are above or below them, depending on their preferred foot.

Hickey’s numbers are almost certainly influenced by an enforced change of position — naturally right-footed, he deputised on the left for the injured Rico Henry earlier in the season.

As for Varane, his position feels significant in a different way — eight of the top-20 two-footed passers in the Premier League this season are centre-backs — a position where, generally, you have more time on the ball and pass in what could be described as safer areas of the pitch.

That said, it is clear that Varane is comfortable in possession with both his right and left foot (statistically, he was the most two-footed passer in the Premier League in the 2021-22 season), and also there is only so much we can read into the position he plays.

After all, the data below shows that two other leading Premier League centre-backs, Liverpool’s Ibrahima Konate (95 per cent) and Spurs’ Cristian Romero (94 per cent) are among the most right-footed passers in the division.

The fact that Konate and Romero typically play on their natural side is a factor. Indeed, a natural right-footer playing as a left-sided centre-back (Marc Guehi at Crystal Palace is a good example), is likely to have a much more even passing split.

Varane’s percentages are particularly interesting, though, given that his United manager Erik ten Hag has spoken in the past about how he considers both Jonny Evans and Victor Lindelof, both naturally right-footed, to be better options at left centre-back in the absence of Lisandro Martinez.

“The build-up is not that fluid when one of them (Harry Maguire or Varane) is playing from the left centre-back position,” Ten Hag said.

The Athletic highlighted during the European Championship three years ago how Maguire, who has spent much of his club and international career playing as a left-sided centre-back, often uses the outside of his right boot to control a ball that is being transferred to him from his right, as opposed to letting the pass run across his body to receive it on his left foot.

That slightly unusual method of receiving means that Maguire is narrowing the passing angle to the left-back outside of him or, in some cases, cutting it off altogether.

In contrast, a left-footed centre-back, or a right-sided centre-back who is more comfortable using their left foot and receiving on the back foot, will be able to make a forward pass that has a totally different trajectory — a pass that could be the difference between a team getting “out” or not in build-up.

Ten Hag touched on this theme not long after taking over at United in summer 2022, when he explained his principles around build-up and talked about how centre-backs who play on their natural side have “an advantage in possession because… you then have better angles for playing out”.

In short, it pays to be a two-footed centre-back these days, and Jarrad Branthwaite at Everton ticks that box.

Although some of his former coaches have claimed he’s right-footed, Branthwaite says otherwise. “I am left-footed, but I’ve got a five-star weak foot on the new FIFA!” the 21-year-old said earlier in the season. In terms of the passing data, Branthwaite’s 59 to 41 per cent split is impressive, especially as he plays on his natural side. “If I’m hitting a long pass, I’ll go with my left; short passes with my right,” he explained.

(Simon Stacpoole/Offside/Offside via Getty Images)

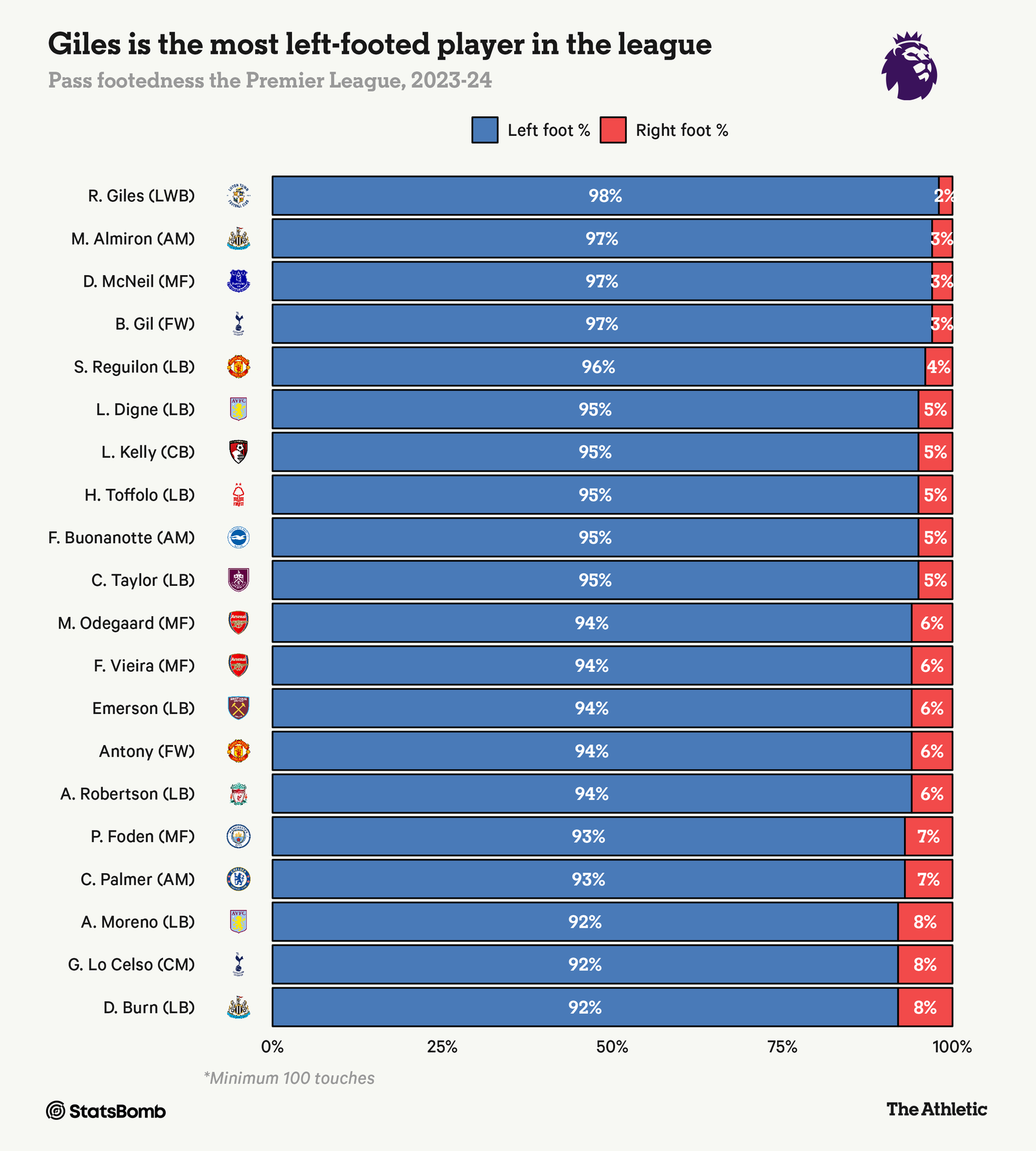

Arguably the most surprising passing data surrounds some midfielders.

In theory, players operating predominantly in the centre of the pitch are among the best technicians and would be expected to pass reasonably frequently with both feet, yet that’s certainly not the case with Martin Odegaard (94 per cent left), Jorginho (95 per cent right), Bruno Guimaraes (96 per cent right), Rico Lewis (97 per cent right) and Kovacic (98 per cent right).

It is hard, however, to argue that the performance of any of those five players suffers greatly as a result of that reliance on their stronger foot.

If Steven Gerrard’s passing figures from yesteryear were available, it’s easy to imagine that they would be similar. After all, only a handful of the 120 Premier League goals Gerrard scored for Liverpool came via his left foot. What Gerrard could do with his right, though (and Zamora brings this up in relation to a conversation about muscle memory and the cleanest strikers of a ball that he has ever seen), was exceptional.

“Stevie G with his right foot was incredible,” Zamora says. “I remember going into England and us doing a keep-ball session and he was just zinging balls, like daisy-cutters — a millimetre off the top of the grass. At Fulham or West Ham, you’d do that and it would come off (once), ‘Brilliant, that looks class’, and everyone was buzzing. Stevie G did that about 10 times on the bounce in England training and I remember thinking, ‘Oh. My. F***ing. God. That’s freakish’.”

Maybe it is less about the value of making a near-equal number of passes with your left and right, and more about having the capability to use whichever is your weaker one in key moments in matches. That feels particularly pertinent for strikers, when a chance comes and goes in a split second. Diogo Jota of Liverpool, who has scored 27 Premier League goals with his right and 20 with his left, comes to mind immediately.

The data for full-backs and wingers (Miguel Almiron of Newcastle, Everton’s Dwight McNeil and Bryan Gil of Spurs are the most one-footed passers) generally shows a heavy reliance on one foot, which is to be expected.

In the case of Antony (94 per cent of passes made with his left foot), United’s scouting reports from the winger’s time at Sao Paulo in Brazil highlighted what was described as an “over-dependence” on his left foot — a view that was repeated after he moved on to Dutch club Ajax.

“What I’m surprised about is that they don’t do more work in training — sometimes going on the right and just doing some right-foot crossing,” said Danny Murphy, the former Liverpool and England midfielder, while summarising for the BBC during that FA Cup tie between Newport and United. “It’s really not that difficult for him to practise it and do it more often.”

Talking more broadly on this subject, Pereira, the former Fenerbahce coach, makes an interesting observation. “It’s easier for a right-footed player to develop his left foot than vice-versa. That’s just my experience,” he says. “Left-footed players tend to be more one-footed. There is probably an explanation involving physiology and motor function.”

There’s an obvious case study here: Arjen Robben.

Opta records show that across the Champions League, Premier League, La Liga and Bundesliga, Robben scored 134 goals with his left foot, 10 with his right, eight with his head and two “others”.

Robben had a signature move and everyone, from the defenders he was up against to the spectators in the stadium, knew that it was coming when he picked up the ball wide on the right. Yet, time and again, Robben cut inside, dropping his shoulder and shifting the ball with the outside of his left foot, and scored.

Robben performs his signature move against Arsenal (Matthias Hangst/Bongarts/Getty Images)

His story, along with those of many other players who have reached the top despite being considered one-footed, provides an interesting counterpoint in the broader debate.

Clichy shakes his head. “If you’re not Robben, and you’re just a regular right-winger who likes to come on his left, my friend, I play against you, I block your left. I send you down the line. That’s it. Your game is over,” he says.

“I will not name names, but big players who played for England, who were regarded as top quality, I played against them — block their right foot, send them on their left: (they are) dead. Or block their left foot and send them down the line on their weaker right foot: dead.

“So I understand when people are saying, ‘Oh yeah, but (Lionel) Messi doesn’t use his right.’ But Messi scores 60 goals in a calendar year.

“That example with Robben, he is an elite player. Bring me someone else and I will show you that if you make him improve on his weaker foot, he will get better results and he will be a better player.

“That’s very logical and no one can really say otherwise.”

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here