The Athletic is attending some of the most ferocious derbies across Europe, charting the history of the continent’s most deep-rooted and volatile rivalries. The series began last season, covering 10 combustible fixtures from Athens to Anfield. We attended De Klassieker and the Derby della Capitale, the Eternal Derby and the Old Firm.

We resumed our journey with trips to Copenhagen, Salzburg, Lisbon and Belfast this season. We were in Ipswich and Zagreb last month, and on Wearside for Newcastle’s visit in the FA Cup.

Now to the Black Country and the volatile meeting of West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers…

It is not even 9am on a half-empty Sunday morning train from London to Birmingham, and yet it is unmistakably derby day.

A chap saunters through the carriage, subtly dropping stickers with Maximilian Kilman’s face on them on tables. As he does so, he casually mutters “Come on you Wolves” in the manner of someone promoting an underground rave.

As we get closer to England’s second city, stopping at Coventry, then Birmingham International, fans from both teams converge on the train. One man who has been drinking bottled lager throws a question in the direction of The Athletic: “Are you West Brom or Wolves?”

For the purposes of this article, there is strict neutrality at play — but with allegiances that stretch back more than 30 years, there is only one answer to give at this juncture.

“Wolves.”

“W*****,” comes the reply.

Welcome to the Black Country derby.

Police and stewards look on as play is halted due to crowd trouble (Marc Atkins/Getty Images)

It may come as a surprise to those who caught the shocking scenes that followed on Sunday afternoon that the validity or ferocity of this match as one of the most passionate and vitriolic derbies in English football is occasionally undermined by the reality that, well, for some West Bromwich Albion fans, Wolves are not their main rival.

Typically that comes down to a matter of either age (Albion and Aston Villa were the main rivals in the region in the 1950s and 1960s) or geography (Albion’s The Hawthorns ground is just over three miles from Villa Park and 10 miles as the crow flies from Wolves’ Molineux home).

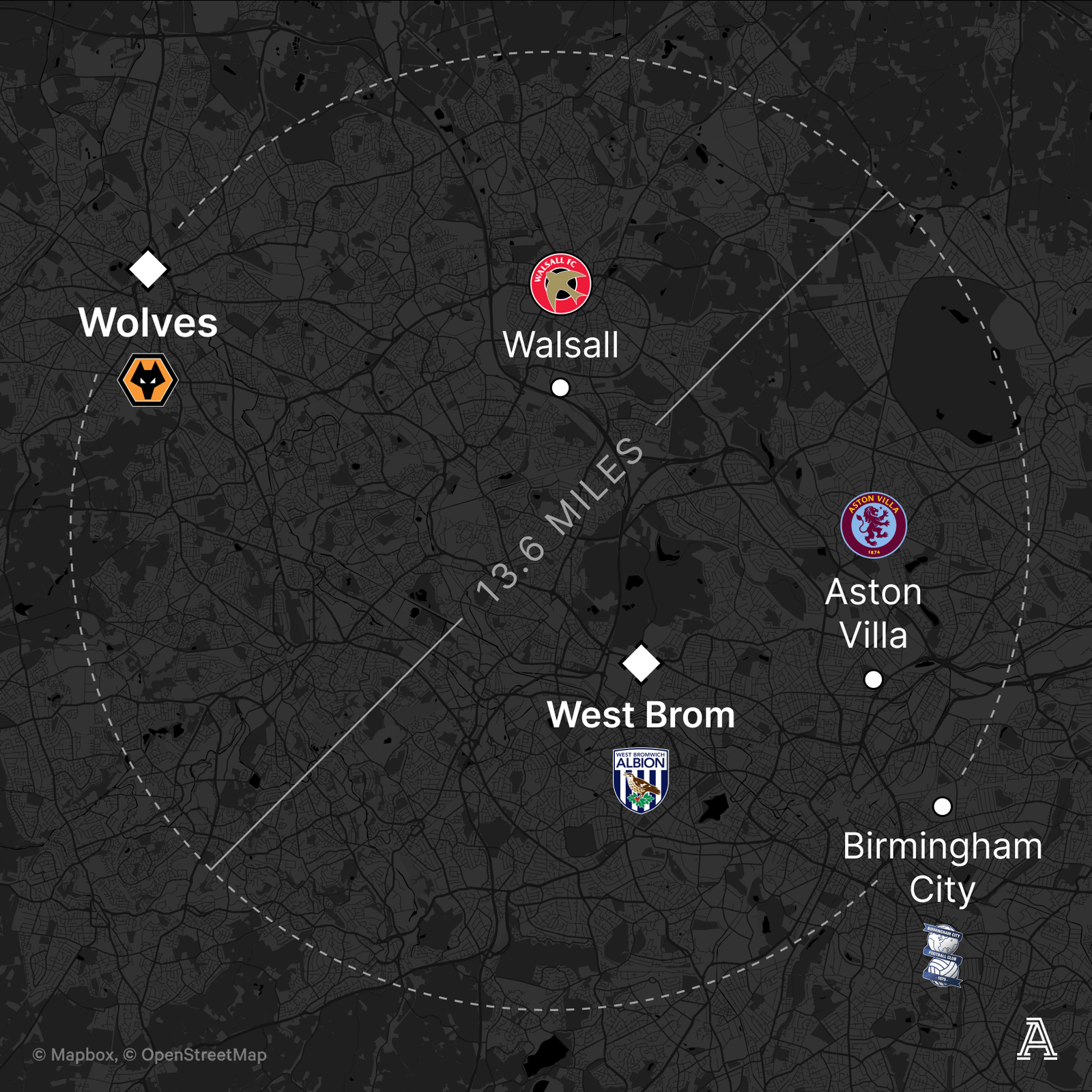

With five football clubs packed into the working-class footballing conurbation that is Birmingham and the Black Country, there is an amalgamation of varying levels of hatred. A smorgasbord of resentment.

It can neatly be split into the Birmingham derby (Aston Villa vs Birmingham City) and the Black Country derby (Wolves vs West Brom). But, as the below map shows, it can depend on where you were born and therefore who your friends, family, school-mates and colleagues support, too.

As for Walsall, given their lower-league status, they are basically the Scrappy-Doo of this royal rumble, aiming shots but landing few. With Wolves being closest geographically, they tend to reserve their strongest vitriol for all things gold and black.

In 2013, when Wolves dipped down to League One, Walsall pulled off a memorable 1-0 win at Molineux. Shortly after full time, a tweet appeared on the official Walsall Twitter account which stated: “Better look (sic) next time you six-fingered, inbred dingle b******s.”

Walsall’s account had been hacked, annoyingly, although the below tweet after the same match remains.

Robert Plant, Noddy Holder, Suzi Perry, Rachel Heyhoe-Flint, Mark from Sam & Mark… Your boys took one ‘ell of a beating…

— Walsall FC Official (@WFCOfficial) September 17, 2013

The feeling certainly is not mutual for Wolves supporters.

For them — and the majority of Albion fans — the Black Country derby, named after an industrial coal and ironworks area of undefined and often contentious boundary lines (some will tell you Wolverhampton is technically not in the Black Country) and immersed in high levels of air pollution in the Victorian era, is the first match they will look for when the fixtures come out.

Not that that has happened for some time.

These two great rivals, whose history is so lengthy their competitive meetings pre-date the start of the Football League in 1888 — they first met in the Birmingham Senior Cup in 1883 and also the FA Cup in 1886 — have not met properly since 2012.

They played each other twice behind closed doors in the 2020-21 pandemic season, and while Albion took great delight in still taking four points off Wolves despite being relegated, they were not proper derbies because, well, what is a derby without fans?

Wolves and West Brom play at an empty Molineux in January 2021 (Adrian Dennis – Pool/Getty Images)

Still, those results continued a trend of near-universal dominance for the Baggies in this fixture over the past three decades. In the previous 33 meetings, Wolves had won just six, and only one at The Hawthorns — back in 1996, when Iwan Roberts and his toothless grin cemented his name into derby folklore with a hat-trick — with Albion winning 16.

That period of white and blue supremacy can be almost bookended by the most memorable of victories for either side of the dividing line, both claimed at the home of the enemy in 1989 and 2012 respectively.

The former revolved around a man named Stephen George Bull. In fact, it was his career-defining switch from The Hawthorns to Molineux in 1986 that, combined with Albion not playing Villa in the league from 1987 to 2002, engineered the Black Country derby’s modern status as one of the fiercest rivalries in English football.

Albion, then a top or second-tier side, sold Bull to fourth-tier Wolves for a pittance, with then-manager Ron Saunders believing the raw striker, who would go from working in a bed factory in Tipton to playing at a World Cup for England in the space of five years, was not good enough.

Bull would score just the 306 goals for Wolves, spearheading the club from its darkest days of near extinction. His goals fired Wolves to the second tier, where the two clubs would regularly meet for the next decade, but it never got better than in 1989 when, on his first return to The Hawthorns, Bull scored a last-minute winner after Wolves’ keeper Mark Kendall had saved a penalty.

The footage is a little grainy, but this is the definition of ‘limbs’.

For Albion, a scarcely believable 5-1 win at Molineux in 2012 not only gave them memories upon which they would dine out for the best part of a decade until the teams’ next meeting, but it also set into motion a chain of events that saw Wolves boss Mick McCarthy fired the next morning.

Wolves failed to win another match for the rest of that season — a dismal 13-match sequence — and were relegated not once, but twice in the next 18 months, tumbling into League One. Talk about a pivotal win.

It also spawned a new variation on the name of their rivals: Wo1ve5.

Peter Odemwingie who, along with strikers such as Kevin Phillips and Bob Taylor, has etched his name into Albion history in this fixture, scored a hat-trick.

“One hundred per cent it was one of my best days in club football,” he later told The Athletic.

“A lot of fans say to me that they forget about the QPR thing (when the striker agitated to leave West Brom for the London club) just because of that day. Memories have healing power. They printed 500 shirts called ‘derby day demolition’. They were sold on the same day. The DVDs were also well-received by fans!”

Odemwingie celebrates his hat-trick in 2012 (Ian Kington/AFP via Getty Images)

As well as pivotal fixtures, the teams have very occasionally gone head-to-head in title and promotion races.

In 1954, Wolves won their first-ever English league title with Albion finishing second, four points behind. Towards the end of that season, in April, they met at The Hawthorns in a game which would go a long way to deciding who would win the league. Albion were a point ahead and already in the FA Cup final, potentially en route to becoming the first team to complete the elusive double.

International fixtures were being played at the same time, so Wolves were without captain Billy Wright and star winger Jimmy Mullen, who played for England against Scotland, but Albion were hit by the unusual call-ups of key players Ronnie Allen and Johnny Nicholls, who would earn only five and two England caps respectively.

Given that Wright, the first footballer to win 100 caps for his country, wielded such influence at the Football Association, a conspiracy theory raged that he had given a cheeky nudge or wink to deprive Albion of their players. It was never proved, of course. Wolves won the game 1-0 and lifted the title the following month, although Albion had the consolation of the FA Cup, the high point of this rivalry in terms of national prominence.

Jeff Astle (arms aloft) scores for West Brom against Wolves in 1964 (R. Viner/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

There was less national prominence in 2002, but the teams’ battle for promotion is still talked about today. No wonder given how remarkable it was: Wolves were 11 points clear of their near neighbours with 10 games of their season in the second tier to go. After 12 years at that level, surely promotion to the promised land of the Premier League was finally theirs?

Nope.

Wolves delivered what is surely one of the greatest chokes in modern English football history, flunking their run-in and being overtaken by, of all teams, West Brom, who hit a golden run of winning form and left their fate in their own hands on the final day thanks to a mythical penalty from Igor Balis in added time at Bradford on the penultimate weekend.

Albion went up to the Premier League for the first time. Wolves had to wait another year. The memories endure for both.

Iwan Roberts and his toothless grin (Aubrey Washington/EMPICS via Getty Images)

To be honest, there is nothing glamorous or sexy about this fixture.

In a similar vein to the Tyne-Wear derby, it involves two working-class towns (OK, Wolverhampton is a city, but also not really) and fanbases for the majority of whom football is an extremely important, passionate, occasionally obsessive part of their lives.

These are two clubs who, in a previous age, enjoyed sitting at the top of the English football tree, winning titles and cups, but who have largely missed out in the game’s era of money-fuelled globalisation and modernisation.

Similar histories, similar stadium sizes and attendances; a similar ceiling of ambition in the Premier League era (Wolves’ highest finish is seventh, Albion’s eighth, and neither has reached a domestic cup final in years); two households, both alike in dignity. Perhaps that is why, other than obvious hate figures in terms of players, they might struggle to find things they truly despise about the other.

Phillips scores for West Brom in the Championship play-offs in 2007 (Jamie McDonald/Getty Images)

“For me, it’s probably the way they change their kit colour every year,” Albion fanatic Paul Faulkner says. “It does my head in, because what is ‘old gold’? One year it looks orange, the next it’s mustard.

“To be fair, in return, I mostly get stick about Tesco carrier bags (in reference to the similarity with the supermarket chain’s colours) or barcodes. So funnily enough, for all the hatred and whatever, most of the banter is about kits.”

Faulkner, a senior figure with the fan group Action for Albion which works to highlight concerns about the ownership of the club, is a braver man than some. He was born — and lives — in Wolves territory. His partner is a Wolves fan. His father-in-law is a Wolves fan. So are many of his friends. He’s in the lion’s den but his father, an Albion supporter, took him to The Hawthorns aged five and, 45 years later, he still has a season ticket.

“It’s always been a massive game,” he adds. “You only have to look at the local press coverage to see that, but outside the Midlands, because we’re wrongly not recognised as a football hotbed, or we’re not the top six, not London, it maybe gets ignored.”

Bull is tackled by West Brom’s Paul Raven (Barrington Coombs/EMPICS via Getty Images)

“In the modern era, the derby exploded with Bully crossing the divide,” the Wolves historian and ardent supporter Peter Crump says. “It’s such an old fixture: two founder Football League members, two traditional clubs. The vast majority of people who support Wolves and West Brom are either from the area, live there or have a link to it, which definitely adds to the rivalry.

“Similarly to a lot of Wolves fans, I’ve got friends who support Albion and I don’t like the nastiness. I prefer the mick-taking and the self-deprecating humour, which is something the area is known for.

“There are endless links in terms of managers and players who have played for both — obviously Bully but, before him, Ronnie Allen and in recent years Joleon Lescott and now Craig Dawson. But direct transfers are very rare. Full-back Paul Edwards was the last in 1994.”

The former Wolves owner Steve Morgan once publicly pleaded for Bakary Sako not to join Albion when his contract expired in 2015. Sako heeded the call and went to Crystal Palace, eventually signing at The Hawthorns three years later. It is not really the done thing.

“It is a fantastic, historic fixture between two grand old football clubs,” Crump adds. “There have been a few thrashings but we tend to operate on similar levels and they are tight games — albeit there will be young Wolves fans who have never seen us beat West Brom. It’s been a while. I can cope with losing the game because I’m used to it!”

Wolves’ Hugo Bueno scores in the under-23s’ Premier League Cup final against West Brom in 2022 (Jack Thomas – WWFC/Wolves via Getty Images)

There is hatred in this fixture, one which local police will demand always kicks off early — but there is nuance too. For instance, a carrot, some pies, goal kicks, some carrier bags and a banned song all link the Black Country derby. Why?

The carrot

In 1991, Wolves claimed an unlikely 2-2 draw despite midfielder Tom Bennett having to go in goal for the final 40 minutes after Mike Stowell was carried off injured. However, the game is also remembered for a Wolves fan running onto the pitch to hand Albion captain Graham Roberts a carrot, the implication possibly being that he thought Roberts was a bit of a donkey (a common football-based insult at the time). Sure.

The pies

For an FA Cup tie in 2007, Wolves were forced to give up the entire South Bank (Molineux’s rowdy end) to Albion due to the competition’s increased ticket allocations. Chief executive Jez Moxey, in a move that many supporters saw as patronising, attempted to placate supporters by offering them a voucher for a pie and a pint. It is unclear if vegan alternatives were available.

Goal kicks

The name Paul Crichton is familiar with this derby purely because, in a game between the sides which Wolves won in 1997, he shanked a seemingly endless succession of goal kicks out of play.

Carrier bags

After that 2007 FA Cup tie — which Albion won 3-0 — their fans left a swathe of Tesco carrier bags over seats in the South Bank as a very visible indication of their famous win.

West Brom fans leave Tesco carrier bags on the seats at Molineux (AMA/Corbis via Getty Images)

Banned song

Both teams have traditionally played reggae stomper The Liquidator before matches (another facet that binds them) but Wolves, on what is commonly thought to be police guidance, banned the song in the early 2000s in the belief its lyrics (“f*** off West Brom… the Wolves!”) helped incite violence. It is still not played today.

But the song was played on Sunday at The Hawthorns, an occasion which crackled and boiled and always threatened to spill over from the moment you could see fans spitting in each other’s directions before kick-off. On a Sunday morning.

Perhaps we all should have seen it coming. So desperate were these two sets of fans to resume their rivalry in person that, in 2022, thousands turned up for an under-23 cup game at The Hawthorns. Wolves had 2,000 in the away end and Albion’s fans invaded the pitch when their young team won after a penalty shootout.

“F*** off to Stafford, the Black Country’s ours,” reverberates around the home stands.

“Always s*** on a Tesco carrier bag,” comes the riposte from the away end.

They join only to curse each other during the loudest rendition of The Liquidator you could wish to hear. Harry J Allstars definitely did not envisage this.

Dawson, once of West Brom, squares up to Kyle Bartley (Marc Atkins/Getty Images)

The atmosphere is glorious but also tempestuous and spiteful. There are incessant boos for former Baggie Dawson (not helped by how he forced a move to Watford in 2019), who now wears gold and is a crucial component in Wolves repelling Albion’s early advances. They sing about geography, about Steve Bull, about Lee Hughes, about incest. It’s nasty.

Objects are lobbed at Tommy Doyle as he tries to take a corner. Wolves fans are thrown out of the Halfords Lane stand after celebrating Pedro Neto’s opening goal. And then in the 80th minute, it boils over.

Another Wolves fan in plain sight makes his allegiances known after Matheus Cunha makes it 2-0 and, in football violence parlance, it all kicks off in some of the most unsavoury scenes this fixture has ever witnessed.

Wolves fans celebrate a win at their bitter rivals (Malcolm Couzens – WBA/West Bromwich Albion FC via Getty Images)

Police storm to that corner of the ground to stop fights or thwart a pitch invasion, while the rest of the force are trying to stop another surge of Albion fans at the opposite corner of the stadium. The players flee and the game is halted. With security so focused on the two obvious areas of chaos, not one, not two, but three pitch invaders pretty casually enter the field of play without being stopped.

One Albion fan says hello to the Wolves bench before walking towards the Wolves away end, while a woman unsuccessfully tries to nutmeg a steward before being carted off. Then one man whose head is completely covered in blood is taken away in a scene resembling a horror movie rather than a football match.

The situation feels completely out of control and, for a while, it seems unlikely that the safety of the players can be guaranteed with police resources so stretched around the ground to quell the pockets of trouble.

Eventually, after more than 30 minutes, the mood calms and the game restarts in eerie near-silence. It feels like most of the stadium is in shock. Sure, it’s a feisty football match, but really?

Police attempt to control the trouble (Adam Fradgley/West Bromwich Albion FC via Getty Images)

All of which takes the gloss off Wolves’ first away Hawthorns win in almost three decades. And this means the sight of West Brom’s Kyle Bartley rescuing his children from the stands will define this latest edition of the derby, rather than images of Neto or Cunha celebrating.

No wonder West Midlands Police cancelled annual leave for the day of the game. No wonder they kicked off at 11.45am — not that that did much good amid suggestions some pubs were open at 5am in Wolverhampton.

“It ruined the day and damaged the reputation of both fanbases,” a dismayed Faulker says. “You could feel it bubbling under the surface but one incident spiralled everything.

“I must say, the operation before and after the match to keep fans apart was immaculate. I didn’t see or hear of any trouble at all outside the ground. But it’s really sad to see; anyone who’s a real football fan regardless of allegiance can’t be happy with scenes like Kyle Bartley going into the crowd to protect his children.

Bartley leaves his pitch with his children after the game is suspended (Shaun Botterill/Getty Images)

“I know people saying they won’t go again to that fixture or they won’t take their children, which is completely understandable.

“There’s always been an edge to it; there’s always been people crossing the line. I remember Albion winning 2-1 at Molineux with Bob Taylor scoring, I came out of the stand and Wolves fans were on the bridge by the subway and lobbing bricks down at us. Some of the sights I saw that day… it was far worse than Sunday.

“Horrific things happen at this fixture but, in terms of the violence, it is often away from the stadium. No cameras. On Sunday, it was in the ground, on TV, there for all to see.”

Neto and the Wolves players enjoy the opening goal (Catherine Ivill/Getty Images)

There were six arrests, with police vowing to make more amid what they called “unacceptable violence”. A low ebb for this fixture but, in truth, also nothing new.

The Black Country derby, plastered across the nation’s TV screens for all to see. It ain’t pretty but, as those in blue and white or gold and black would tell you: “It’s ours.”

(Top photos: Getty Images; designed by Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here