When Valencia hired former midfielder Ruben Baraja as coach last February, the mood around the club was not good.

A team including too many expensive veterans and less motivated loan players was sliding towards the bottom of the table in La Liga, while the Estadio Mestalla regularly shook with angry protests against the club’s majority shareholder Peter Lim.

In late April, Baraja’s side were drawing 1-1 at home to fellow relegation candidates Real Valladolid, when a point would have left them in the bottom three. With 93 minutes played, 19-year-old Los Che midfielder Javi Guerra, making just his third senior appearance, slammed home a 20-yard winning goal.

A few weeks later, Alberto Mari, 21, headed an 88th-minute winner as Valencia took three more crucial points at Celta Vigo. In the next game, Diego Lopez, 20, scored the only goal as Real Madrid were beaten. Lopez scored twice more in the last two weeks of the season, in crucial draws with Espanyol and Real Betis, as Valencia finally secured safety on the final day.

“When you are not getting results, you have to look for solutions,” ‘El Pipo’ Baraja tells The Athletic. “We needed freshness, energy, bravery, and sometimes the players from the youth system give you that. When you realise you have things to lose, it hobbles you, but these younger players had nothing to lose. And the team saved itself in the final hour.”

Two more homegrown products of Valencia’s academy — centre-back Christian Mosquera and winger Fran Perez — also played big roles in escaping a relegation which could have been disastrous given the club’s historic debts of over €300million (£256m; $322m at current rates) and still unresolved two-stadiums problem.

This new generation, christened ‘El Quinto del Pipo’, has given many at Valencia more faith for the future of their club.

“The situation was difficult, but those of us coming from the youth team came in with a lot of motivation to find our place in the team, at Valencia, at the top level,” says young winger Lopez. “The staff and other players helped us a lot. And we were able to do well.”

Lopez celebrates scoring at Mallorca in October. Valencia are now seventh in La Liga (Rafa Babot/Getty Images)

There is an acceptance at Valencia that had the senior team not been struggling last season, Baraja would not have taken such risks in throwing in so many youngsters. However, many at the club maintain that it was not just good fortune that so many talented young players were capable of taking these opportunities and competing.

“Valencia has always owed a lot to its academy, so it has to look after it,” says corporate director Javier Solis. “Often a necessity can become a virtue. But that virtue does not appear, without a lot of work behind it. Three, four, five, six young players performing at this level does not just happen by chance. Our academy is one of the best in Europe.”

Valencia first bought the land in the Paterna neighbourhood where its training ground sits in 1974. In the 1980s, players used to deliberately kick the ball out of play, so they could jump over the wall and grab an orange off the trees.

Now enclosed by a business park and two motorways, the 180,000 square metre site contains eight pitches (six natural, two artificial), dressing rooms, club offices, a media centre, an academy residence, a restaurant and the 2,250 capacity Estadio Antonio Puchades, where the Valencia Mestalla youth team and the women’s senior team play.

About 80 per cent of all players in the academy are from Valencia, while almost half of the current senior squad also have deep links to the region. Club captain Jose Gaya arrived aged 11, left-back Jesus Vazquez was five, midfielder Hugo Guillamon was six, Yarek Gasiorowski was seven, Perez was nine, Mosquera was 12. Guerra arrived in 2019 from neighbours Villarreal, when he was 16. Asturias-born Lopez was 19 when he joined from Barcelona’s youth system, having previously spent time at Real Madrid.

“We are really identified with Valencia, the city and region, we feel its principal ambassador in the world,” says academy director Luis Martinez. “That emotional part might seem really romantic, but a kid who knows that their parents dream of seeing them play at Mestalla will want to stay here and do that. We also want those who come from outside, from Granada or Madrid, to feel part of our family too, and have that same dream. And they know we will give them the opportunity to do that here.”

Baraja was made Valencia coach in February 2023 (Aitor Alcalde/Getty Images)

All the club’s 33 different male and female teams, from under-6 ‘cherubins’ to the two senior sides, train each day at the Paterna complex, which is decorated with explanations of the academy’s three core values: sentiment (sentiment), valentia (bravery) and germanor (brotherhood).

Martinez says no rigid tactics or systems are imposed at youth level as “we believe that different coaches playing different systems adds to the richness of a player’s development”. Talent managers at each age level closely monitor each player, with feedback from colleagues in medical, physiotherapy and nutrition departments, and objectives set out for each individual’s development. The club pays the tuition for many academy players at the Mas Camarena private school close to the training ground. There are courses for parents, as fathers and mothers of top prospects also need education and support.

Parents of young footballers are encouraged to consider their role in development (Valencia CF)

There is also a focus on internal development for coaches and staff at today’s Valencia. Baraja himself had his first coaching job at Paterna after retiring as a player. Seven of his nine staff members, including assistant Chema Sanz, also worked their way through youth levels. Another club legend, Miguel Angel Angulo, is the coach of the Valencia Mestalla youth team, who play in Spain’s third tier (Primera Federacion).

“You can see how the first team benefits from the good work done at the academy,” says sporting director Miguel Angel Corona. “Fifty per cent of our first team were previously with our youth side. Today’s Valencia wants to be a club built up from its roots. It is no coincidence that those who are really helping the team now have a deep connection to ‘Valencianismo.’”

Valencia’s academy scouting coordinator is Jose Jimenez, who has worked at the club for 27 years. During his time, Raul Albiol, David Silva, Isco, Pablo Hernandez, Jordi Alba, Juan Bernat, Paco Alcacer, Ferran Torres and Carlos Soler all passed through Paterna on the way to becoming full Spain internationals. Their sales brought in over €200million.

“The current regime is very concerned with the academy, and invested more money than I ever had before,” Jimenez says. “They are getting a return on that: homegrown products who, under Baraja, have formed a group that creates a lot of excitement, and results. This is all about developing players for the first team, so the club does not have to make million-euro signings.”

When Lim took control of Valencia in 2014, club president Layhoon Chan (now back in the role) said that developing young players would be a priority. A wider focus include targeting global talent. United States international midfielder Yunus Musah and Georgia goalkeeper Giorgi Mamardashvili both arrived at Paterna’s residence aged 16.

Musah was sold last summer to AC Milan for €20million. Mamardashvili, now 22, is currently Valencia’s No 1 keeper, and according to the local press has drawn interest from Premier League clubs Manchester United, Newcastle United and Tottenham Hotspur.

According to the International Centre for Sports Studies (CIES), there are 29 Valencia academy products currently playing across Europe’s top five leagues (as illustrated in the graphic above). Corona says the club spends about €10million a year on its youth system, which it sees as an investment in the club’s future, whether through transfer revenues or performances for the first team.

“The sales of Alcacer, Soler and many other players have been a source of income for our club,” sporting director Corona says. “Yunus came here aged 16, and went through the full process of development and learning with us. We have no complex about saying this is a benefit of the work done in the academy. It helps to create a better Valencia, especially as we all know the club’s delicate financial situation.”

After the ‘Quinta del Pipo’ helped Valencia to beat relegation last season, Baraja signed a two-year contract in June. His hand was evident in the club’s transfers last summer, as was the hierarchy’s desire to cut the wage bill.

Senior squad members Edinson Cavani and Samu Castillejo were allowed to leave. Lopez, Mosquera, Guerra and Perez are all now regular starters and among the team’s most important players.

“The club realised that it was more important to have young players, committed, with energy, and hunger,” Baraja says. “It is an opportunity for them. They know that we are there to protect them, to look after them. There might be five games where they play really well, then the next one they forget what they have to do. But we have to just keep repeating it with them, insisting a lot. We worked a lot with them, but they deserve all the credit.”

Javi Guerra celebrates his winning goal against Atletico in September (Diego Souto/Quality Sport Images/Getty Images)

Baraja has regularly had to fill gaps in his thin squad by promoting more players from the club’s youth side. Defenders Gasiorowski (19) and Cesar Tarrega (22), midfielders Pablo Gozalbez (22) and Hugo Gonzalez (20) and forward Mario Dominguez (19) have all had minutes in La Liga this season. In January’s Copa del Rey game against Cartagena, winger David Otorbi became the club’s youngest-ever player at 16 years, two months and 19 days.

“This season it has been even more brutal,” Baraja says. “Instead of three or four homegrown players, there have been games with seven or eight. The average age of the team has been incredible.”

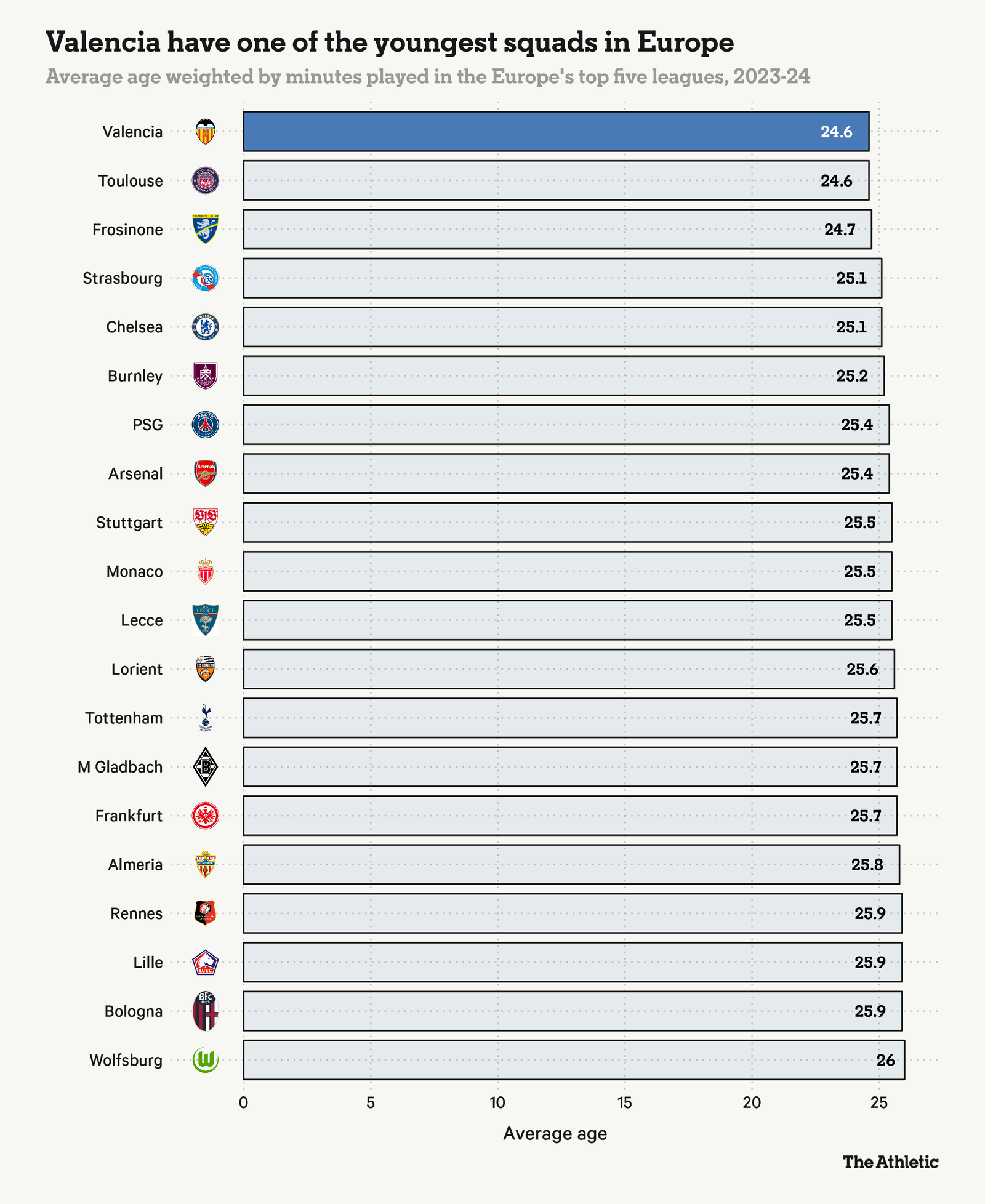

This means that Valencia have had the youngest squad in La Liga, and when looking at average age weighted by minutes played in Europe’s top five lives, theirs is the joint youngest with Toulouse.

An early sign that this season could go well came when nine players developed at Paterna contributed to September’s 3-0 La Liga win over Atletico Madrid, with Guerra sealing victory with another strike from outside the area.

“When you start to play as a kid you always have that dream, but not everyone can fulfil it,” Guerra says now. “The Atletico game showed us we were capable of competing with the bigger teams near the top of the table. So it motivates you to keep improving. We know we are privileged to be out on the pitch, and we have to keep working, so that it does not end here.”

January’s transfer window was a reminder of Valencia’s realities. With the team well clear of the relegation zone, Lim sanctioned the exit of their most experienced defender, 33-year-old Gabriel Paulista, to Atletico Madrid. Just one player was signed, 21-year-old winger Peter Federico from Real Madrid’s youth team on loan. A deadline day move for Sevilla centre-forward Rafa Mir, who spent six years at Paterna as a teenager, broke down acrimoniously.

“Experience is very important,” Baraja says. “Senior players have much more knowledge of the game. There is always a bigger risk, with so many young players. We are protecting them. They are our players, our heritage, and everyone knows the financial situation of the club. That means we need to develop them, bring them on.”

Still, last weekend’s 2-1 defeat of Almeria made it five wins from six in La Liga, a run which has lifted Baraja’s team to seventh in the table. The mood at Mestalla is currently much brighter than it has been in some years, with the unlikely idea opening up that the ‘Quinto del Pipo’ could be playing in UEFA competition next season.

Baraja is well aware that his young side will inevitably suffer from dips in form and results, but does admit a hope that this generation of Paterna graduates can backbone a first team which can again challenge for trophies.

“These are things which you need to consolidate,” Baraja says. “I would like for this to be the start of something nice for the future. That this team, in two or three years, can be back at the level that Valencia has historically been at. That is my dream, what we are aiming for. They are playing well now, so imagine in a few years, with more ambition, how they can improve.”

(Top photo: Jose Miguel Fernandez/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Read the full article here