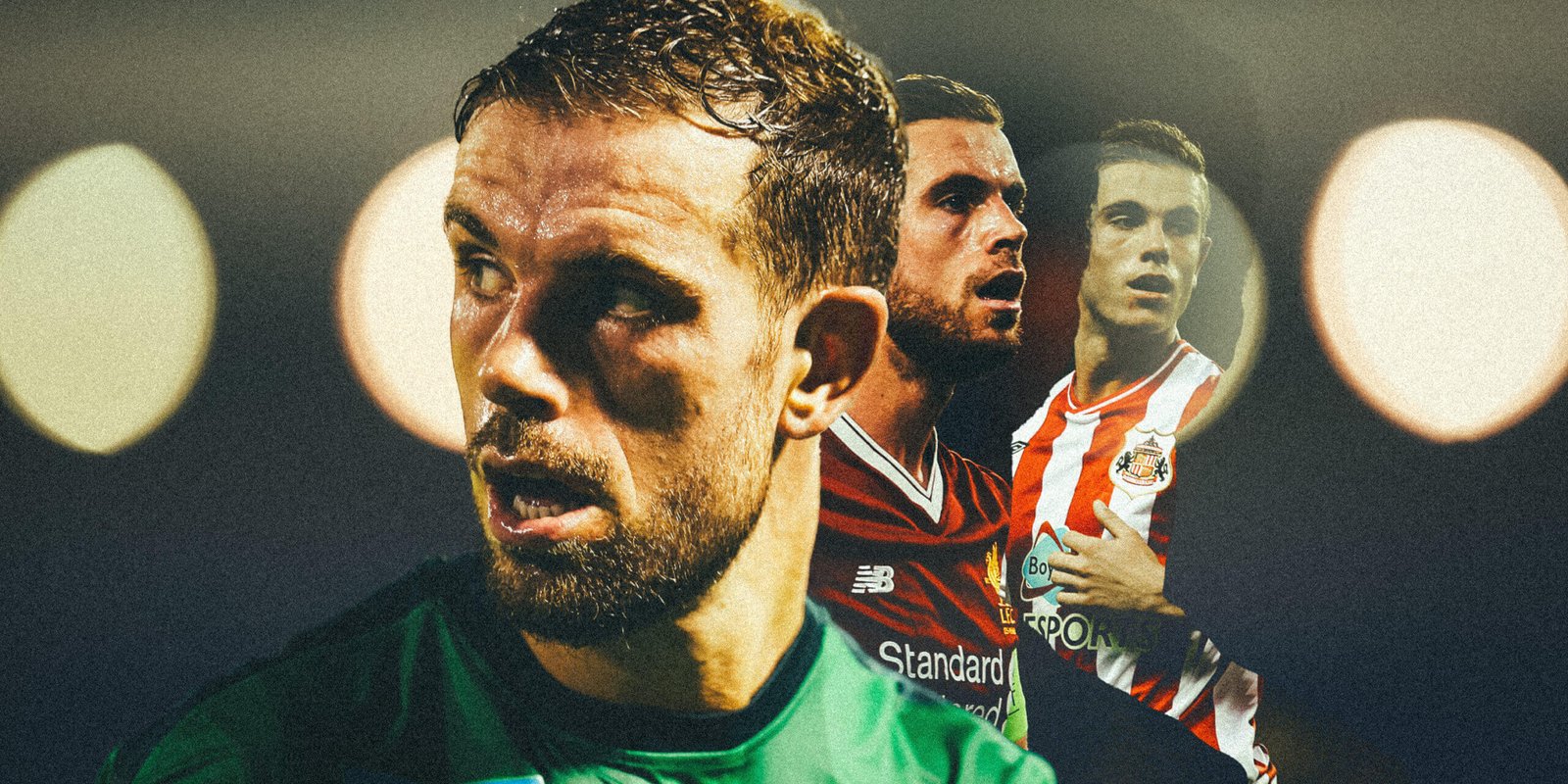

Six months ago, Jordan Henderson was one of English football’s most widely respected figures; an exemplary professional who had made the most of his talents to become one of the most idolised players of his generation, all while retaining an impressive moral conscience.

His decision to move to Saudi Arabia changed all that at a stroke. Now, he was the hypocrite who had set his principles — particularly around support for LGBTQI+ rights — aside in pursuit of a big payday.

The abrupt end of his stint at Al Ettifaq and move to Dutch champions Ajax has pitched him back onto one of Europe’s grandest football stages, but his reputation remains broken.

But what do fans in the European cities he has called home make of him and the decisions that have shaped his career? We canvassed feelings in Amsterdam, Sunderland and Liverpool.

Amsterdam: ‘He’s just the player we need here’

Jordan Henderson joined Ajax last week after ending his spell at Saudi Arabian club Al Ettifaq.

It is three hours before kick-off and, with slush on the ground, there is a cluster of people gathered next to the Ajax retail store built into the Johan Cruyff Arena.

They wait here for personalised shirt printing to appear through a serving window and, according to staff, the majority only want one name on the back.

Among them is Martin van Der Linden, who has parted with €20 (£17; $22) to add Henderson and the No 6 to his newly purchased Ajax away shirt. Reports locally suggest Henderson’s is already the fastest-selling jersey on record.

“He’s just the player we need here, a leader” says Van Der Linden, an Ajax supporter arriving early for the visit of RKC Waalwijk. “They’re selling a lot of his merchandise, he’s very popular.”

Martin van Der Linden shows off his Henderson Ajax jersey (Phil Buckingham/The Athletic)

Inside the store, there are Henderson towels, mugs and cushions on sale; items that are materialising quicker than the work permit that delayed the player’s debut for at least another week.

Henderson’s short stint in the Saudi Pro League is barely mentioned here. Few players of the England midfielder’s stature wind up in the Eredivisie and the route he has taken to the Dutch capital is seemingly immaterial. They talk of Henderson’s reputation at Liverpool rather than one being tarnished.

“It doesn’t matter where he’s come from,” adds Van Der Linden. “This is a good example that Saudi is f***ed up. Players only go there for the money. He’s the first example of a player who has come back to Europe because it’s not so good. This is an opportunity for him to show what he’s still capable of.”

Henderson kits on show in Ajax’s club shop (Phil Buckingham)

Amsterdam is set to be Henderson’s home for the next two and a half years and, since arriving on Thursday of last week, he has already taken in the sights on a bike. “Exploring my new city,” he wrote on Instagram on Saturday, complete with the love-heart-eyed emoji.

The reception afforded to Henderson has been warmer than a city that has been covered in a light dusting of snow. Any cynicism in Ajax making a 33-year-old their highest earner has been washed away by the promise of what Henderson is set to bring to a team enduring a miserable season. There is a craving for experience and leadership.

It extended to the BLVD 020, in the shadow of Ajax’s home, which gradually filled on Sunday afternoon with match-going supporters escaping the cold.

“He’s a big player for us and a big step for Ajax to sign him,” says Jordi, attending the game with his young son. “Normally, a big player like Henderson doesn’t come to Holland. They play in England or Spain or Italy. I didn’t hear a single bad word from my friends about Ajax signing him.”

The adjoining table cares little for the last six months either. One stresses Henderson is “not Jesus Christ” in an attempt to curb the obvious anticipation, but even that is an acceptance of the excitement the new arrival has engendered.

Perhaps only Ajax could have found the resources to bring England’s midfielder to Holland. For all their troubles this season, winning only one of their opening eight games to sit bottom of the league in late October, this remains a club with a storied history — and one that’s still in the Europa Conference League. Ajax’s haul of silverware hangs on banners from the roof of their 55,855-capacity home.

Henderson was there on Sunday, watching on from the stands draped in a red-and-white striped scarf. The first stoppage of the game, inside two minutes, showed Henderson on the giant screens to bring huge cheers from a full house. It felt a far cry from the Prince Mohamed bin Fahd Stadium in Dammam, where Henderson spent those loveless months. A broad smile and a grateful wave followed.

Henderson in the stands at Ajax (Jeroen van den Berg/Soccrates/Getty Images)

So did a demonstration as to why Ajax pushed so hard to sign Henderson. An enterprising start came with an early opener through Brian Brobbey, but RKC’s comical equaliser, poked in by Michael Kramer, revealed the shortcomings of John van’t Schip’s young team that included nine players aged 22 or under. There was chaos without control until the hosts eventually ran away to a 4-1 win. Captain Steven Bergwijn, too, convinces few he is the leader Ajax need.

“Everyone is excited he is here,” says Edwin Janssen, an Ajax fan outside of the stadium. “He will bring balance to the team, helping the young guys. Maybe he will make our defence better, too.”

The smile suggests he is not convinced. “It doesn’t matter where he comes from. Footballers can go there (to Saudi) and make a lot of money. Maybe they don’t like it when they get there, who knows? But we don’t care.”

Henderson has found a club that has opened its arms to greet him and a first meaningful introduction will likely come next weekend when Ajax travel to lowly Heracles. If not, it will be the visit of league-leaders PSV Eindhoven on February 3.

“He brings a lot of experience,” said goalscorer Brobbey afterwards. “We’re all excited.”

Good vibes only for Henderson in Amsterdam.

Phil Buckingham

Sunderland: ‘We’d definitely want him back’

Jordan Henderson joined Sunderland’s academy in 1998 and went on to play for the first team before leaving in 2011.

Friday night in Sunderland, on the streets where Jordan Henderson first made his name, the faithful are on their way to a Championship match against Hull City at the Stadium of Light. Here, aged 18, Henderson made his home debut in November 2008.

Less than three years later, in the summer of 2011, Liverpool paid £16million ($20m) for a young, dynamic midfielder. Away with England at the Under-21 European Championships in Denmark at the time, it was eight days before Henderson’s 21st birthday.

Elated to be part of a hoped-for new era at Anfield under Kenny Dalglish, Henderson did not forget where he came from. He had been at Sunderland from a young age and made 79 first-team appearances.

“I owe so much to Sunderland,” Henderson writes in his autobiography. “Everything I was as a player when I moved to Liverpool, I owe to the club and its coaches. And everything I was a person I owe to my mam and my dad and my friends and the city where I grew up.”

Henderson as a teenager at Sunderland (Christopher Lee/Getty Images)

His father, Brian, still attends Sunderland matches.

Henderson’s home town felt pride when he first played for England and also when he began to speak up on social matters. In certain quarters, that remains.

Outside Sunderland’s Deaf Club on North Bridge Street, a long-standing pre-match gathering place for supporters, Gordon and Donna are holding pints and revealing how much Henderson’s Wearside origins mattered to them and still do. “He’s a local lad and we’ll stand behind him,” Donna says.

They have over 80 years of watching Sunderland between them and witnessed Henderson emerge under Roy Keane in the Premier League. Henderson had returned from a loan spell at Coventry City to play 38 games in the 2009-10 season. He was voted the club’s young player of the year that season — and the next.

“He gave his all to Sunderland and with him coming through the academy, in my eyes, he was a true professional on the pitch and off it,” Donna says. “He’s a local boy, went to Farringdon School; he’s had to work his socks off.

“Then — after Covid and whatever — he’s had to do what’s right for his family. So he went to Saudi with his friend Steven Gerrard, who will obviously have been a big part of it. And if his family is not happy, he’s got to move on.”

Gordon agrees and refutes accusations of hypocrisy on Henderson’s part.

“No because you go to work to earn a living — nothing else,” he says. “He’s been getting paid a lot of money, but you can’t blame him for that. He’s done nothing wrong. We’d definitely want him back, Id’ love to see him on the pitch here again.”

Down the street inside the Fans Museum, Karen Whitaker, a season ticket-holder of 35 years, shares similar views. “He’s a local lad, hasn’t come from money, a genuine lad with a normal mam and dad. When he captained England, we were proud of him.”

What did she make of his decision to go to Saudi Arabia?

“Why not? A football career isn’t that long. Yes, he made his millions, but if I was offered 300 grand a week, I’m going to take it. You would. After Ajax, I honestly believe he’ll finish at Sunderland. He’s wanting to go to the Euros, but after that, if the club want him, why not?”

Henderson playing in the Wear-Tyne derby for Sunderland in 2011 (Stu Forster/Getty Images)

No individual or small group can ever be said to represent any fanbase, merely a snapshot, and Martin Walker offers a different take. He, too, has been watching Sunderland for decades and says he was impressed by Henderson’s social advocacy at Liverpool.

“Footballers were getting a lot of flak from the government and Jordan Henderson was one of the key people getting captains at clubs together,” he says. “All through his time at Liverpool, I looked at him with a degree of pride at a local lad becoming so successful and a role model. Quite a lot of pride, to be honest.”

Walker was not alone. In 2019, Henderson was proposed as a possible recipient of Freedom of the City by Sunderland City Council. He said he was “honoured” but did not wish to accept until his playing days were over.

The offer is in a drawer but, as Walker says, “I don’t think it’s appropriate now. That’s the sadness. I don’t look at his NHS stuff in a different light — he did it and it made a difference. It was a really good thing to do.

“But things like the Rainbow Laces, it just looks hypocritical. Meaningless. For three months over there (Saudi Arabia), he’s tainted that image. I think it’s really sad. At best, he made a financially motivated decision, but quite a stupid one. Henderson just looks (like) another mercenary now.

“I wouldn’t want him to come back, which is a shame.”

Sunderland do not have an official LGBTQI+ fan group as other clubs do. They are considering launching one in 2024.

Michael Walker

Liverpool: ‘We’ll always feel let down, but his legacy is on the pitch’

Jordan Henderson played for Liverpool between 2011 and 2023, making 492 appearances and winning eight trophies.

“He barely fitted the kit when he first came.”

John Gibbons, of The Anfield Wrap podcast, is remembering his early impressions of a slight, skinny Wearsider signed from Sunderland for £16million in the summer of 2011. “He looked like a good technical player, but was he a bit nice?”

Jordan Henderson was part of a signing spree led by then-director of football Damien Comolli, with a new and much-trumpeted focus on data analytics. As with Andy Carroll, Stewart Downing and Charlie Adam, his unquestioned potential did not immediately show up in the numbers.

Although a regular under manager Kenny Dalglish, Henderson was often played out of position and struggled in a faltering side. When Comolli left later that season, Henderson was cited as a key reason. “The day they sacked me, they said you made a big mistake with Jordan Henderson,” he told The Athletic in 2020. “I said: ‘OK, I think you are wrong’.”

Henderson thought so, too. The following summer he was, infamously, offered the opportunity to join Fulham by Brendan Rodgers as part of a deal that would see Clint Dempsey move in the opposite direction. Henderson refused and vowed to fight for his place.

That stubborn determination to succeed was offset by a personable nature, which made him much-loved at Liverpool’s Melwood training base.

Andy Renshaw, Liverpool’s former head of physiotherapy, was working in the academy at the time. “Even at that young age and even though he wouldn’t have a clue who I was, he still said hello,” he recalls. “There was no ego with Jordan at all.”

Henderson’s triumphs with Liverpool are immortalised in murals around Anfield (Shaun Botterill/AFP via Getty Images)

Opportunities did arrive under Rodgers, who was won over by Henderson’s work ethic and hard running. After Liverpool’s near miss of a title challenge in 2013-14, he was considered a regular and after Steven Gerrard’s departure the following year, he was deemed the only viable candidate to replace him as captain.

Yet any fears that Henderson lacked the personality to succeed Gerrard were not shared inside Melwood. “It was almost expected when you’ve got a character like him,” says Renshaw.

Henderson’s leadership style was never far removed from the quiet, unassuming figure who had arrived from Sunderland four years earlier and he did not try to imitate Gerrard.

“When he needed to be, he was very vocal. He had no issue pulling players up,” says Renshaw. “With those players who don’t always say a lot, they get listened to the most because when they speak, they really need to say something.”

Initially, Henderson was not present in the team as much as he wanted to be. He struggled with plantar fasciitis — a chronic pain at the base of his left foot — which limited him to just 53 appearances in Jurgen Klopp’s first two seasons.

The condition required almost constant monitoring and Liverpool’s medical staff conducted an exhaustive investigation into how to manage his injuries — from testing the softness of the pitches at Anfield and Melwood to adapting the insoles of his boots.

Henderson, as always, absorbed everything. “He was attentive, he listened, he applied himself in any of the work we’d ask him to do,” says Renshaw.

The pain became manageable and the following season was when, Gibbons believes, Henderson began to “feel and play like a Liverpool captain”.

Having joined Emlyn Hughes, Phil Thompson, Graeme Souness and Gerrard in the pantheon of Liverpool’s European Cup-winning captains in 2019, his bond with fans was strengthened the following year during the Covid pandemic when, as well as helping to end his club’s three-decade wait for a league title, he organised efforts by Premier League captains to raise funds for frontline NHS workers.

By that stage, Henderson was already a vocal champion of LGBTQI+ rights and the most prominent supporter of the Premier League’s Rainbow Laces campaign. Members of Kop Outs, Liverpool’s LGBT+ fans’ group, left meetings impressed by his genuine interest and enthusiasm.

Henderson’s support for LGBTQI+ issues won him plaudits at Liverpool (Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

Publicly, it left the impression of a socially conscious footballer in touch with supporters in the stands. And that, ultimately, is what left a sour taste in the mouth of many of those same supporters last summer when he reunited with Gerrard, now Al Ettifaq head coach, on a three-year contract worth a reported £700,000 per week.

He was not the only Liverpool player to depart for Saudi Arabia last summer — Roberto Firmino and Fabinho did the same — but his decision to join a less-competitive league in an authoritarian state that criminalises the very people he had advocated and campaigned for stung.

“I love Bobby Firmino — but nobody’s going for a pint with him,” says Gibbons. “But Henderson had this everyman appeal that, to be fair, he’d helped cultivate.”

Frustrations with Henderson’s decision were not only down to the apparent hypocrisy. Some felt that, as captain, he should have stayed and fought for his place during a time of transition.

The timing of his departure meant Henderson received no send-off for his 12 years of service, but the circumstances meant that by the time he was first pulling on an Al Ettifaq shirt, many Liverpool fans had already moved on.

There was certainly no talk of any possible return to Anfield once it became clear Henderson was seeking an exit. With Klopp’s side top of the Premier League and powered by a rebuilt midfield, the rancour of the summer has subsided, leaving only the question of Henderson’s legacy.

“I think with a little more distance, his legacy will be that he was captain of one of the greatest sides this club has ever had,” says Gibbons.

“He was the leader of the gang and they were the best gang in town. We’ll always feel a little let down by Jordan, but his legacy is what he achieved on the pitch.”

Mark Critchley

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here