This is part of the How Football Works series, a piece-by-piece look at the mechanics of the game

In English — a language that is, let’s face it, not always associated with elegant midfield play — we tend to call the player at the base of midfield a ‘defensive midfielder’ or ‘holding midfielder’, but in possession, the Spanish ‘pivote’ is more evocative.

The pivot is the hub of the wheel, the fulcrum of the lever, the central point around which the whole system turns (or ought to, anyway, when the ball isn’t sailing over their head in fine English fashion).

The turning isn’t just a metaphor because a pivot plays in the middle of the pitch, they spend a lot of time receiving the ball in tight spaces and deciding which way to send the possession next. The direction of their turn as a pass arrives at their feet has a whole cascade of knock-on effects for both teams. If it looks like a small thing on TV, barely even a choice, that’s because a lot of the important work happens before they even touch the ball.

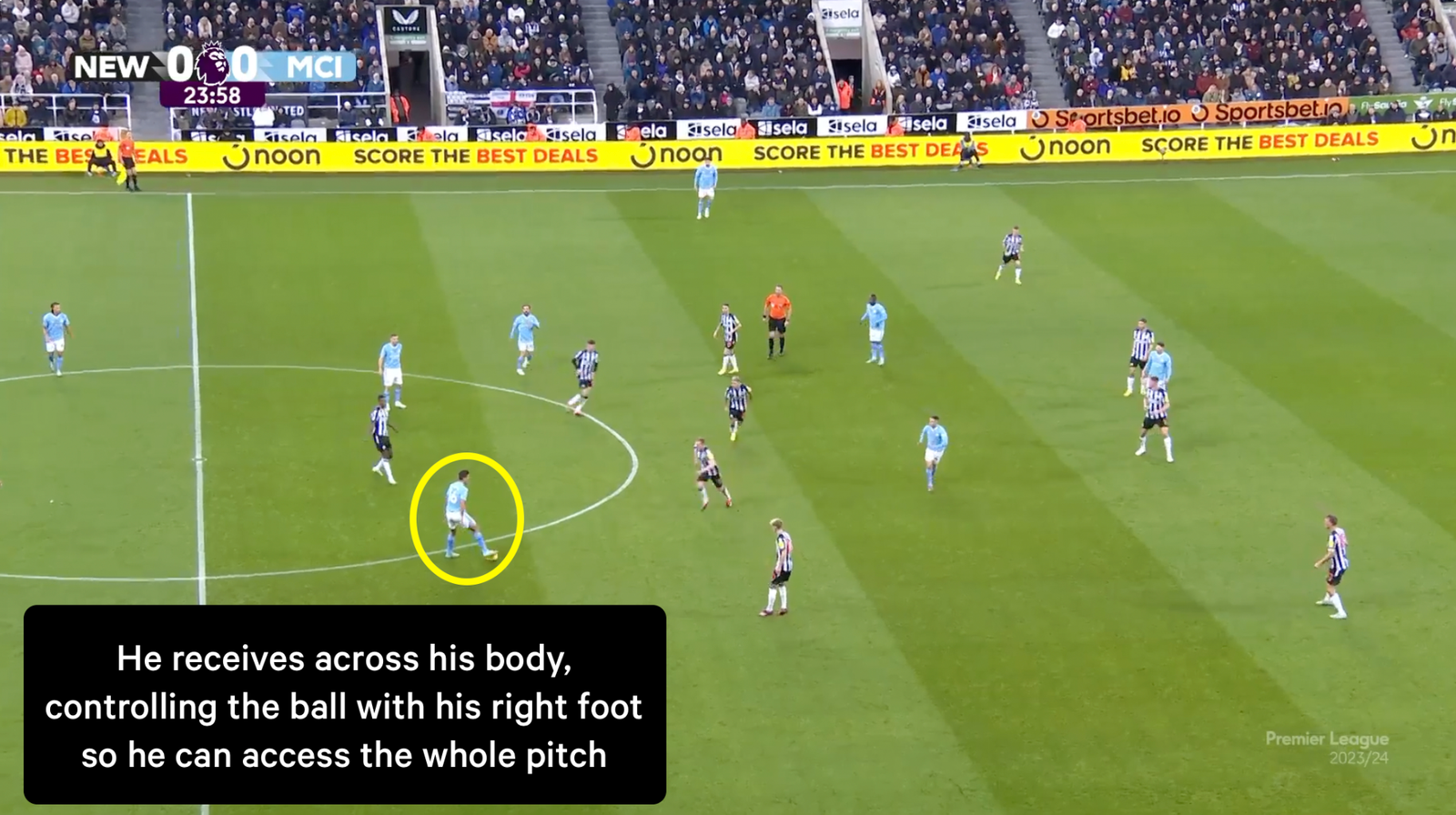

Different situations call for different turns, but a general rule drilled into players from a young age is to try to receive ‘across their body’, meaning they should orient themselves almost perpendicular to the direction of the pass and let the ball roll to the foot that’s farther away from the passer (this is also known as receiving “on the back foot” where “back” is relative to the origin of the pass, not the other team’s goal).

Receiving across the body makes technical and tactical sense. On a basic mechanical level, it lets the player cushion the pass with their instep for a more controlled first touch, bringing it to rest in front of them so they can take the next touch on either foot. At the same time, it opens up the receiver’s body to maximise the angle of play. Because the defence shifts to follow the ball, a player receiving from one side of the pitch is more likely to find a team-mate in space on the opposite side by taking a wide turn.

This rule is especially important when a team is circulating possession in midfield, swinging the ball from side to side to try to break down the defence. By receiving across the body while facing play, a pivot creates options to play through or around the second line.

If this is all sounding sort of jargony and abstract, don’t worry, we’ll look at some examples to make it make sense. Specifically, we’re going to take a look at some differences in how Rodri and Declan Rice receive the ball.

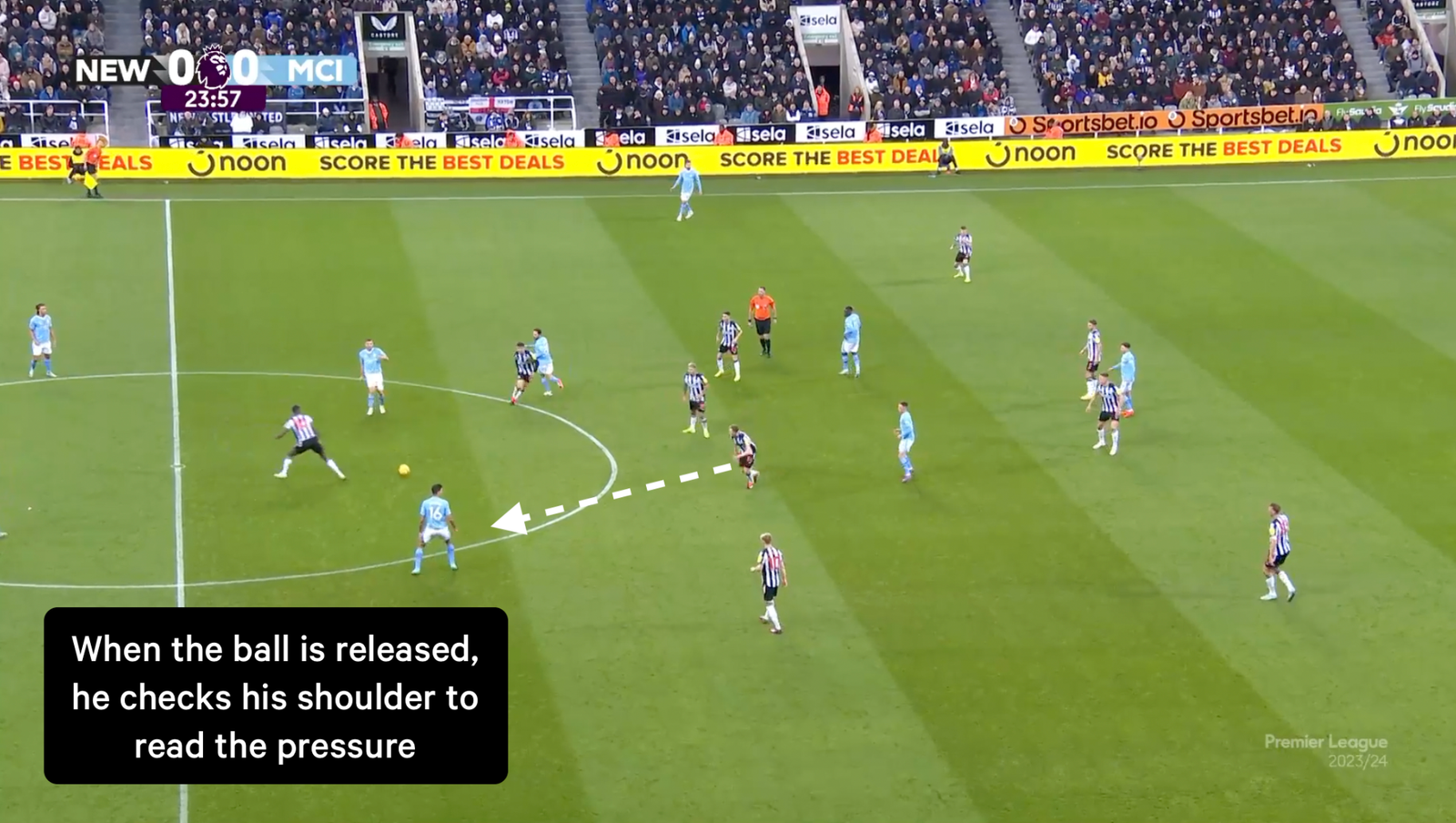

Receiving across the body on the preferred foot

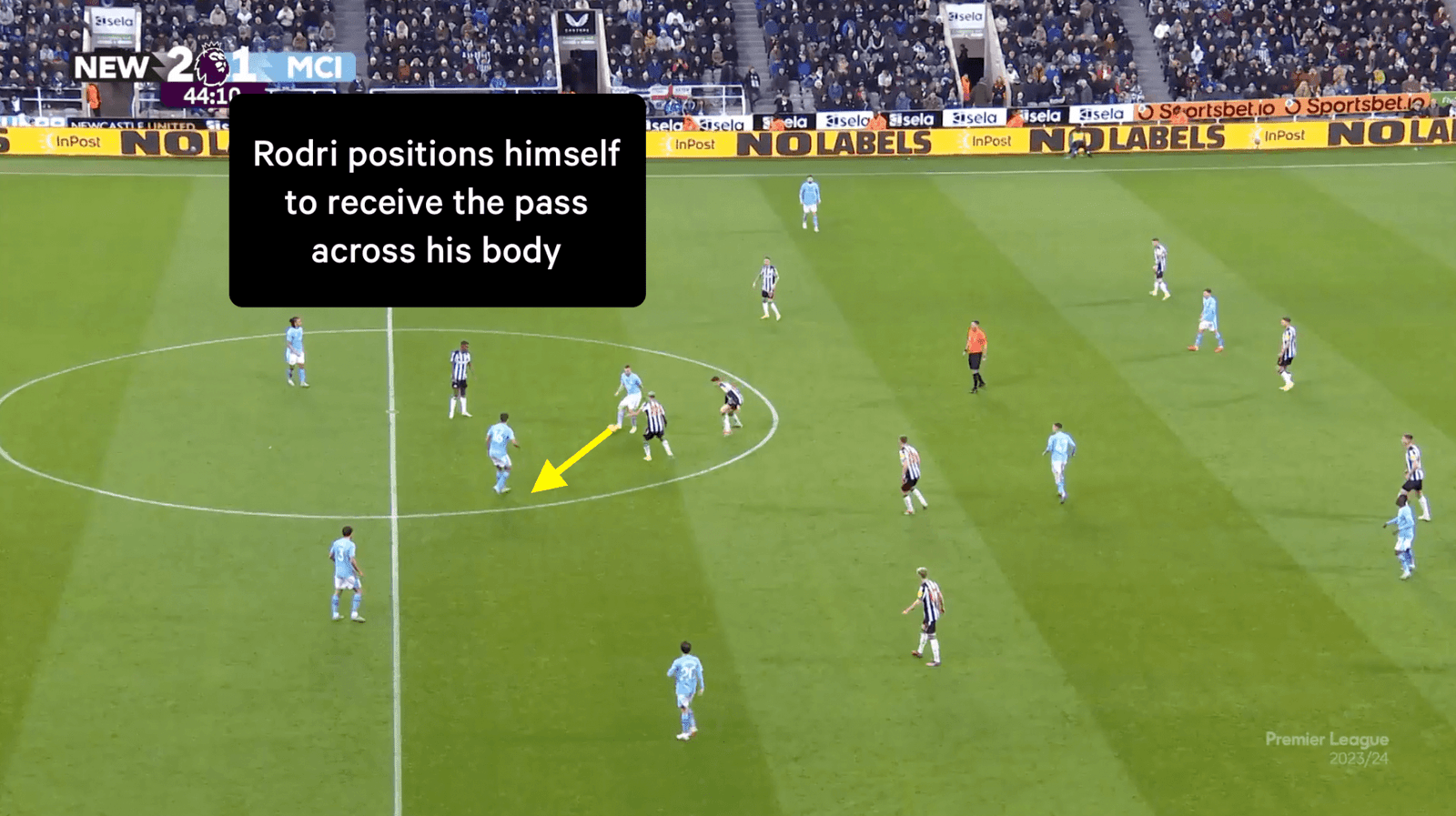

You won’t find a better pivot in football than Manchester City’s Rodri, who keeps his whole team ticking with flawless fundamentals in midfield. Watch how he receives a short sideways pass across his body against Newcastle United to find Kyle Walker in space…

There’s no secret to what Rodri is doing here. It’s Football 101. But even the tiniest little nuances in how a player receives the ball can make a big difference in what happens next.

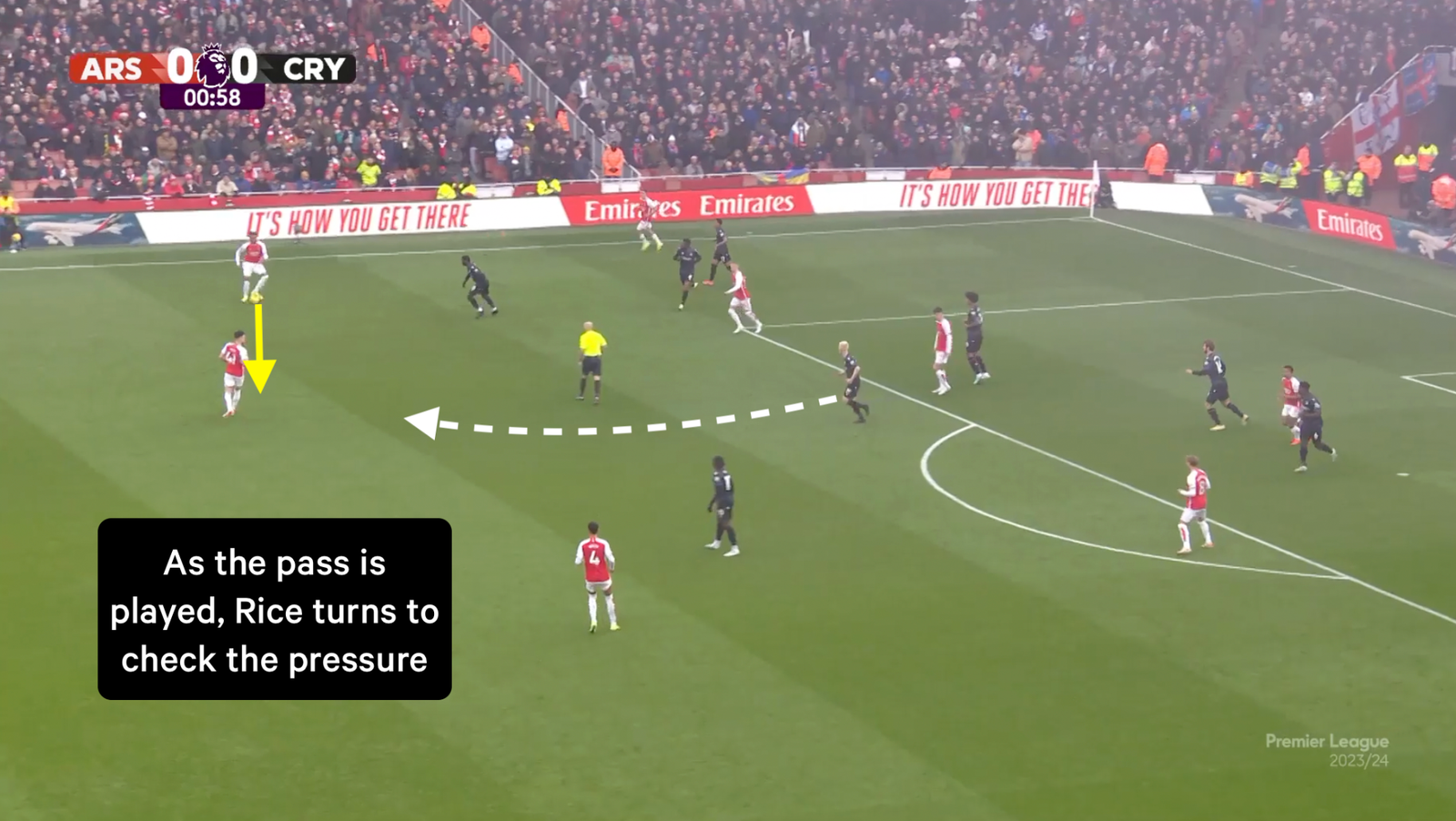

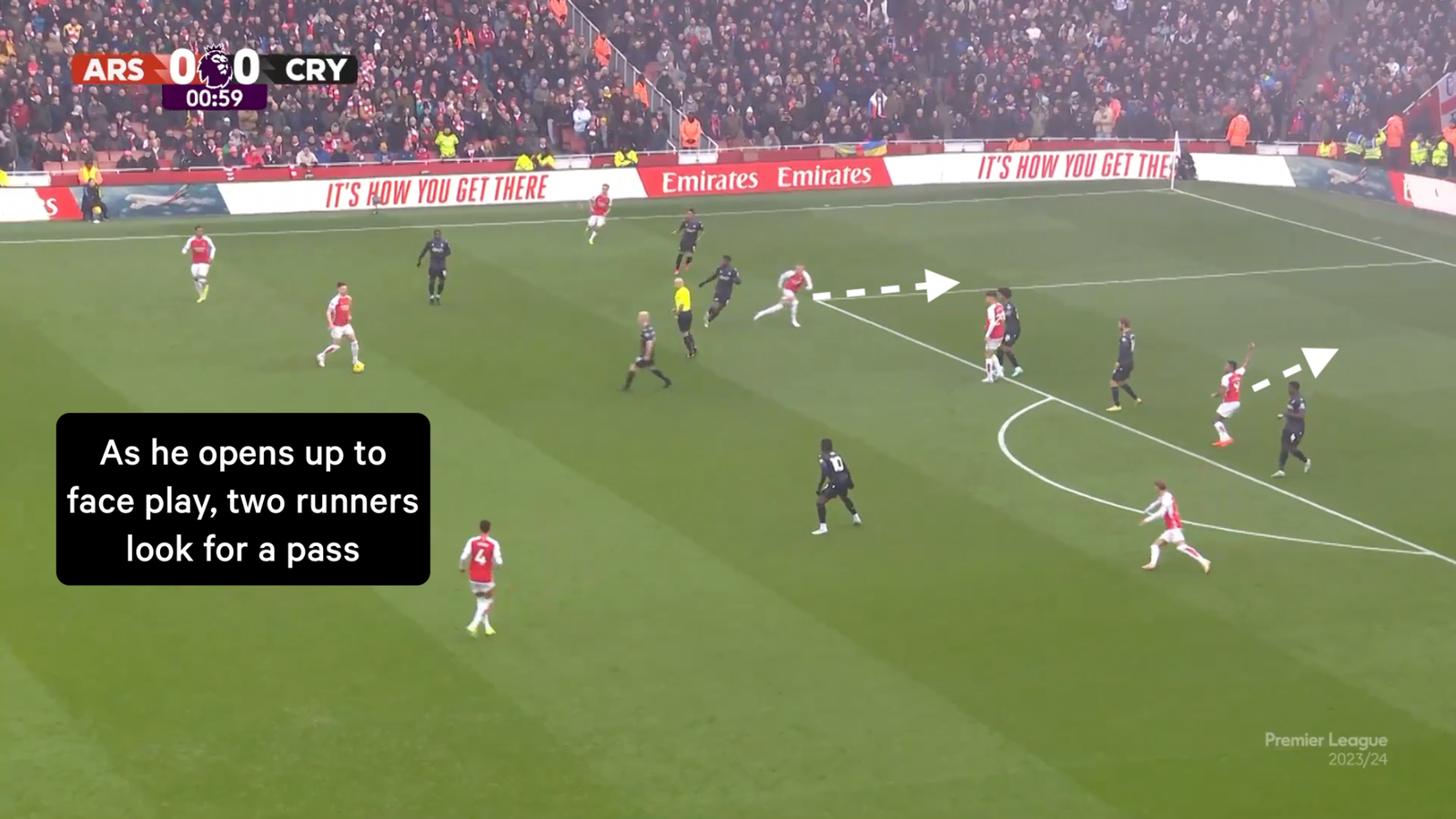

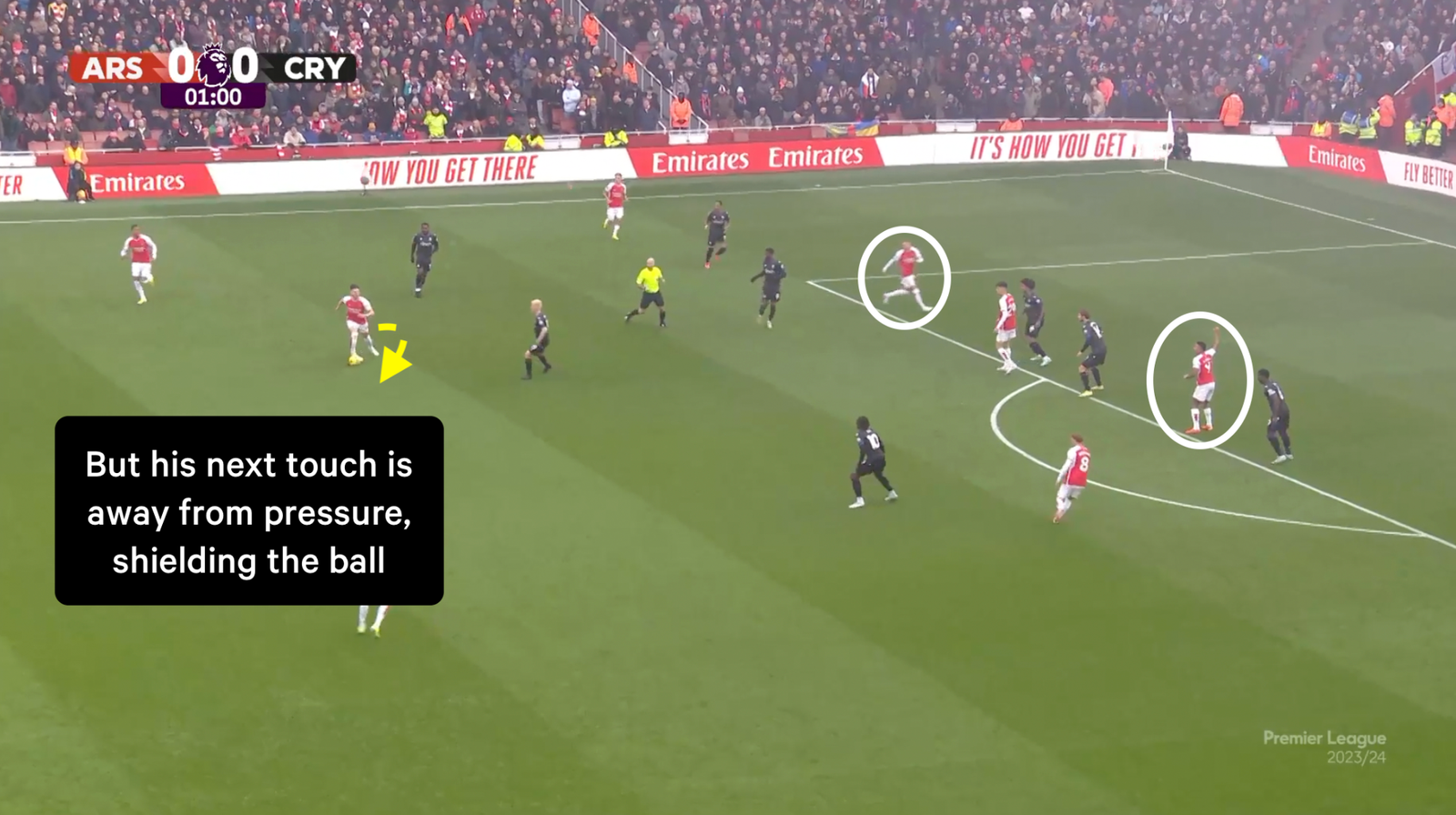

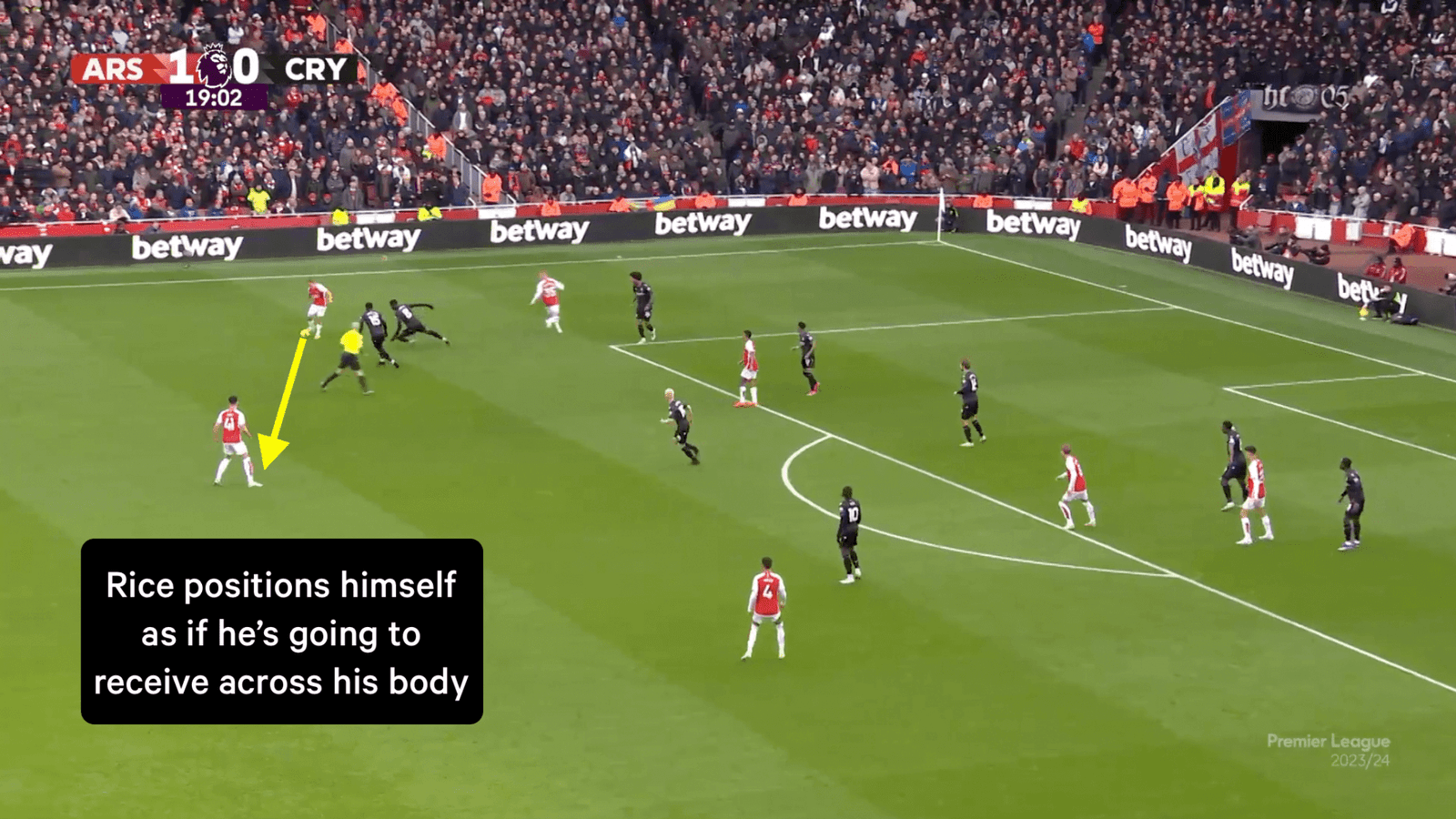

Compare that play to this one from Arsenal midfielder Rice, who’s also receiving a short sideways pass across his body in the example below, but with subtle differences…

Rice doesn’t do anything wrong in this sequence. A forward pass over the top is harder than a diagonal out to the wing and it’s a matter of taste whether that’s a chance the team want to take. The point here is that the decision to play it safe is already made at a mechanical level in the split second the player receives the ball.

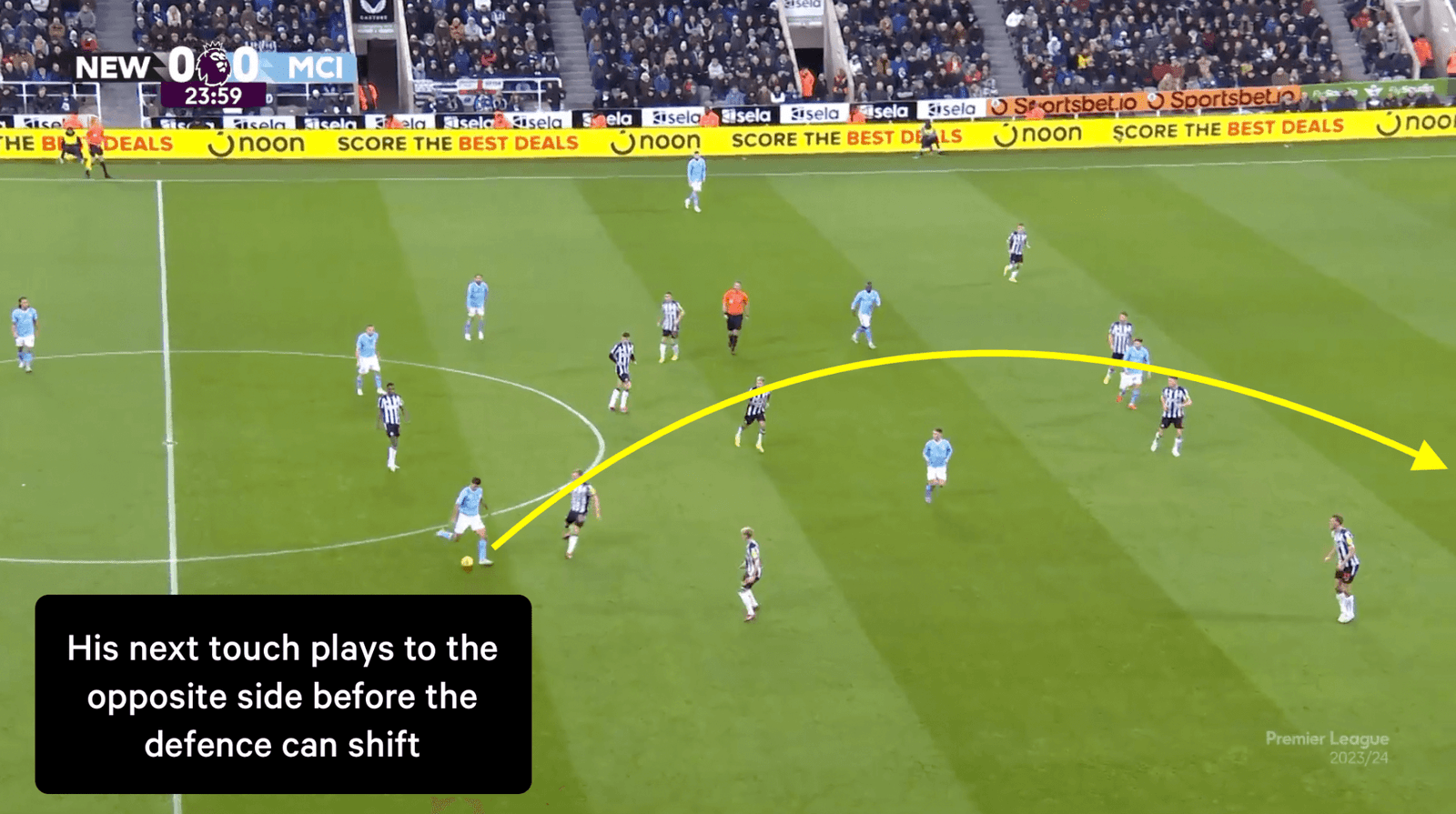

It has to happen that fast because the pivot is typically under pressure as soon as the ball arrives. When an opponent steps out of their defensive line to close down a pass, it cranks up the danger but also creates an opportunity. If the pivot can think fast, there may be a way to play through the hole his marker has left behind — and again, finding it starts with receiving across the body.

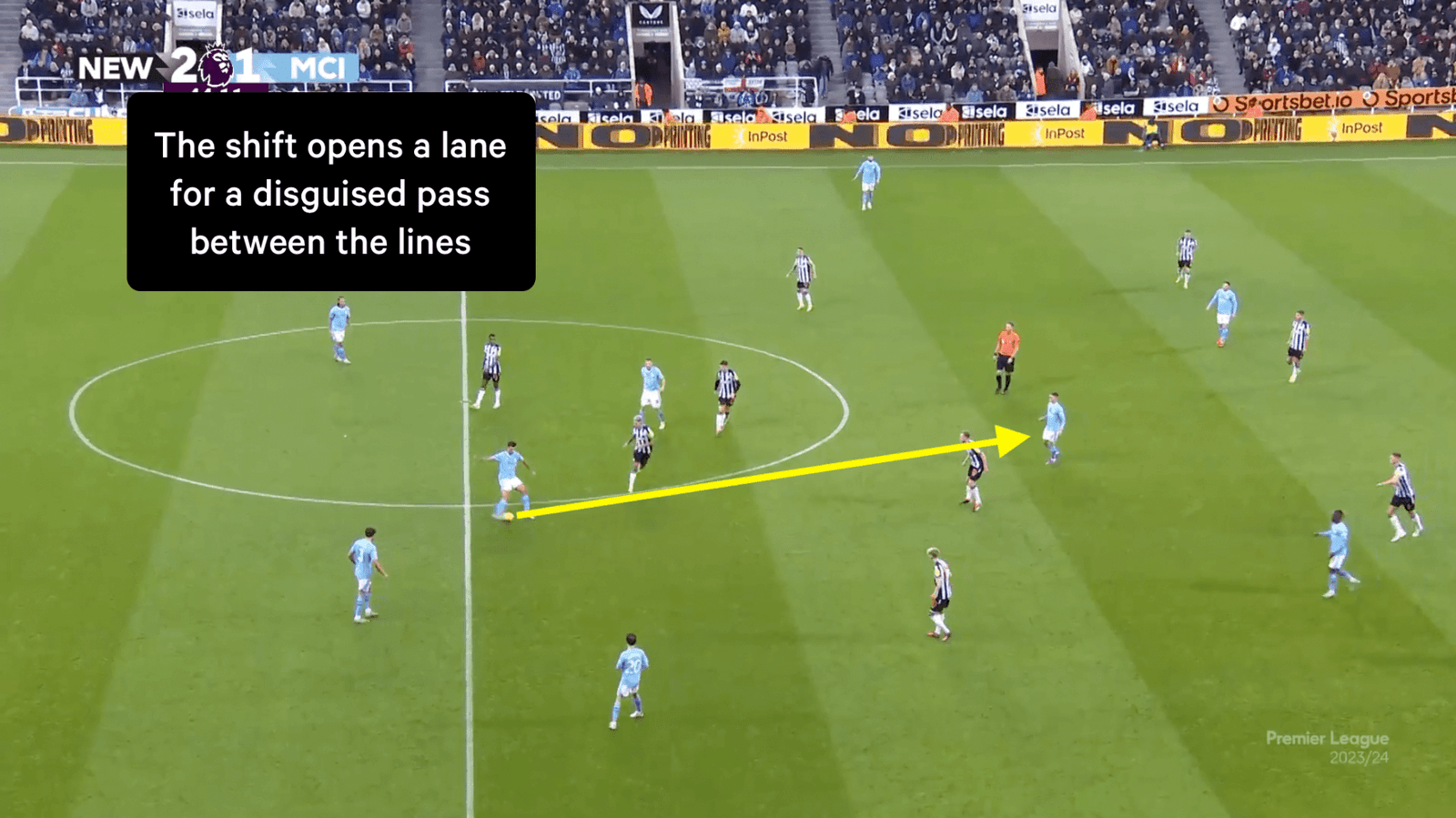

Turning out wide doesn’t just create the option to play out to the wing. Shifting the defence in that direction also creates gaps in the middle for a line-breaking pass. When the ball is already on the instep of the pivot’s preferred foot, he can shape his body toward the wide option but play a ‘disguised pass’ (shaping up in one direction but passing at a different, unexpected angle) through the middle instead.

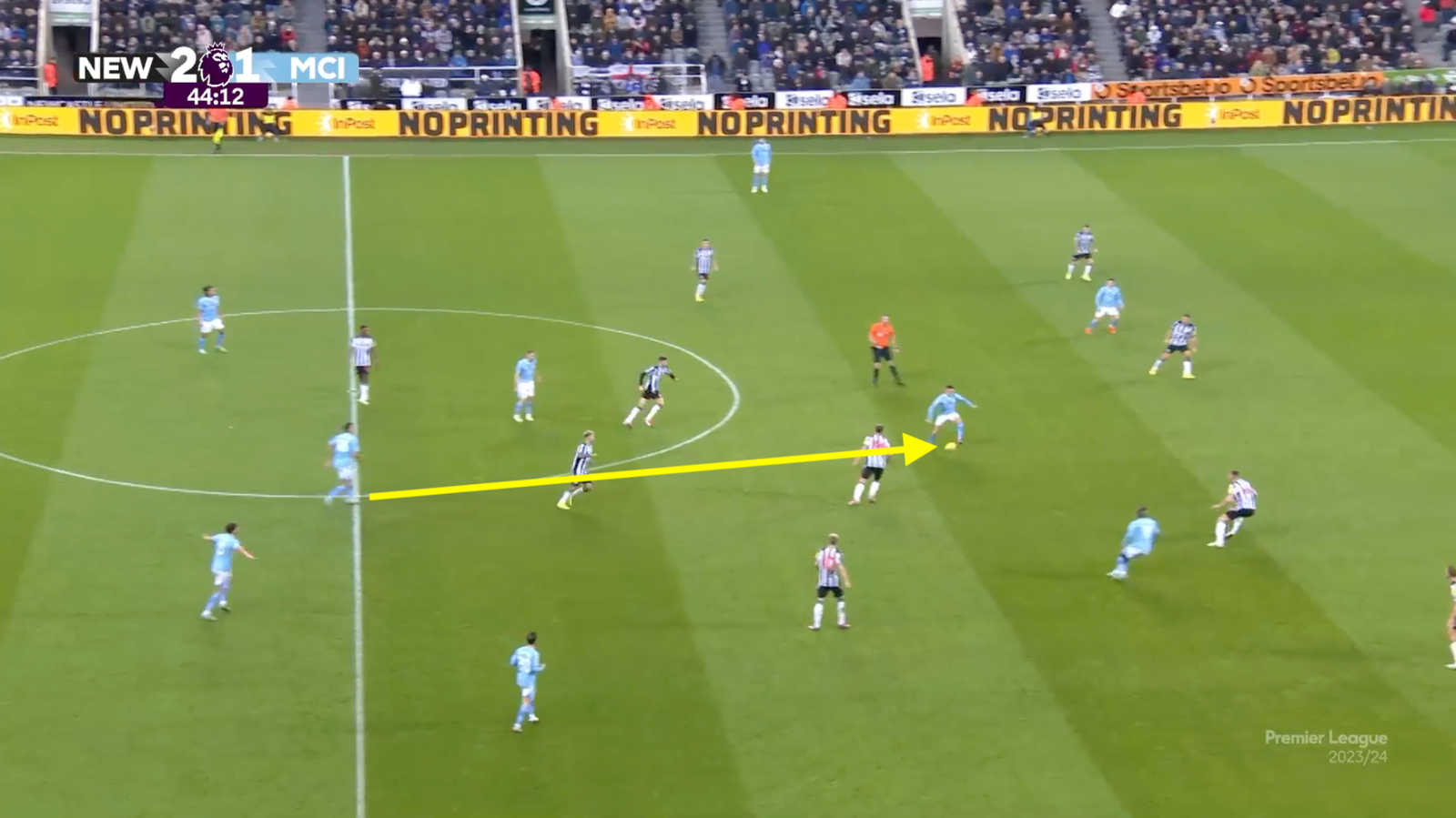

Here’s Rodri pulling that trick against Newcastle…

If Rodri hadn’t received across his body at an open angle, Bruno Guimaraes’ pressure would have closed off that lane and Sean Longstaff might have stayed narrow enough to intercept it. Rodri’s body position implies he might try a wider pass to Walker on the wing or Jeremy Doku in the middle, thereby opening a lane to Foden in the middle.

Turning inside instead of across

Every rule has exceptions and not every sideways pass needs to be received across the body. When opponents start to anticipate that pattern, sometimes the smart play is to turn back inside instead, catching the defence off balance.

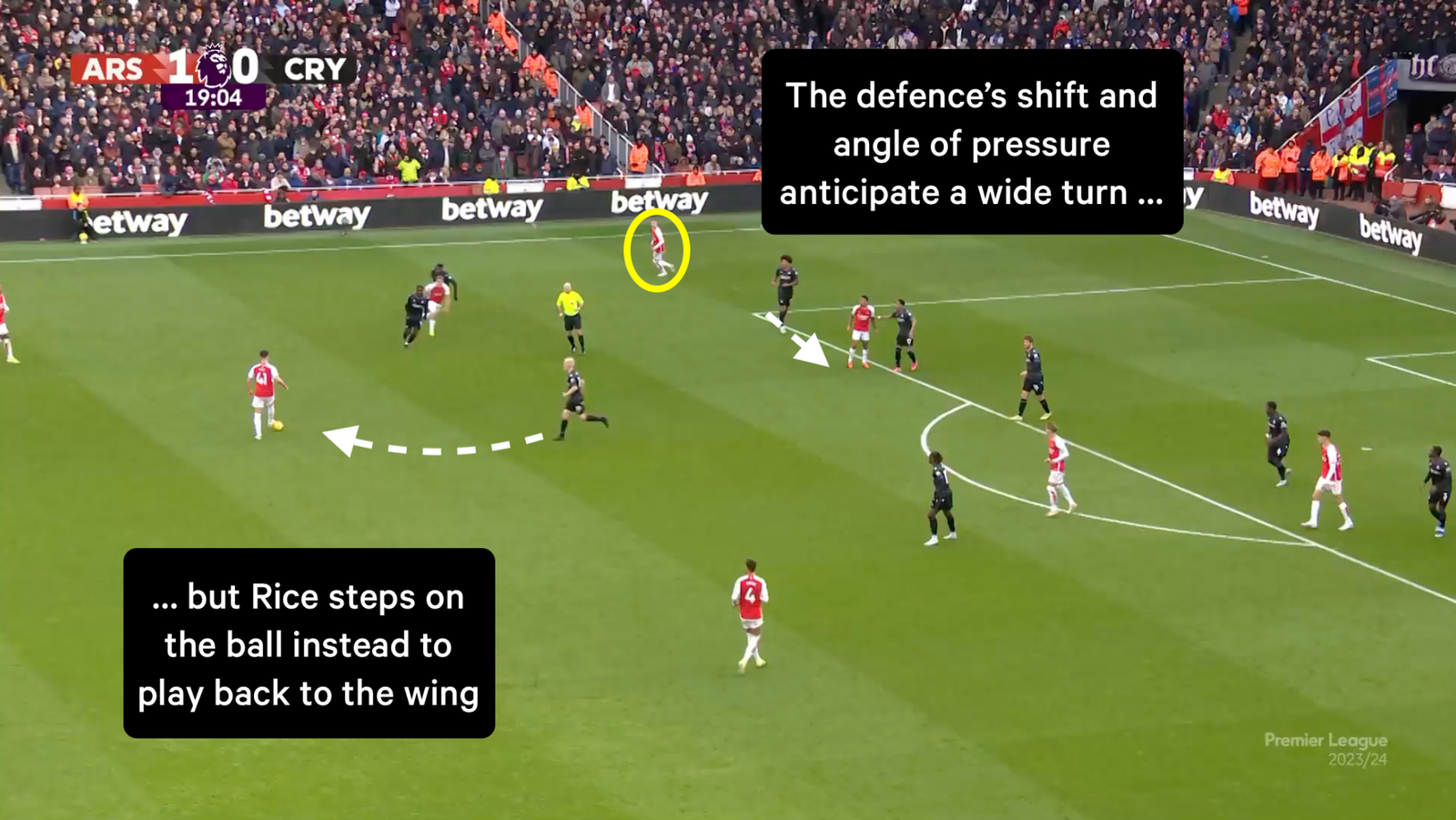

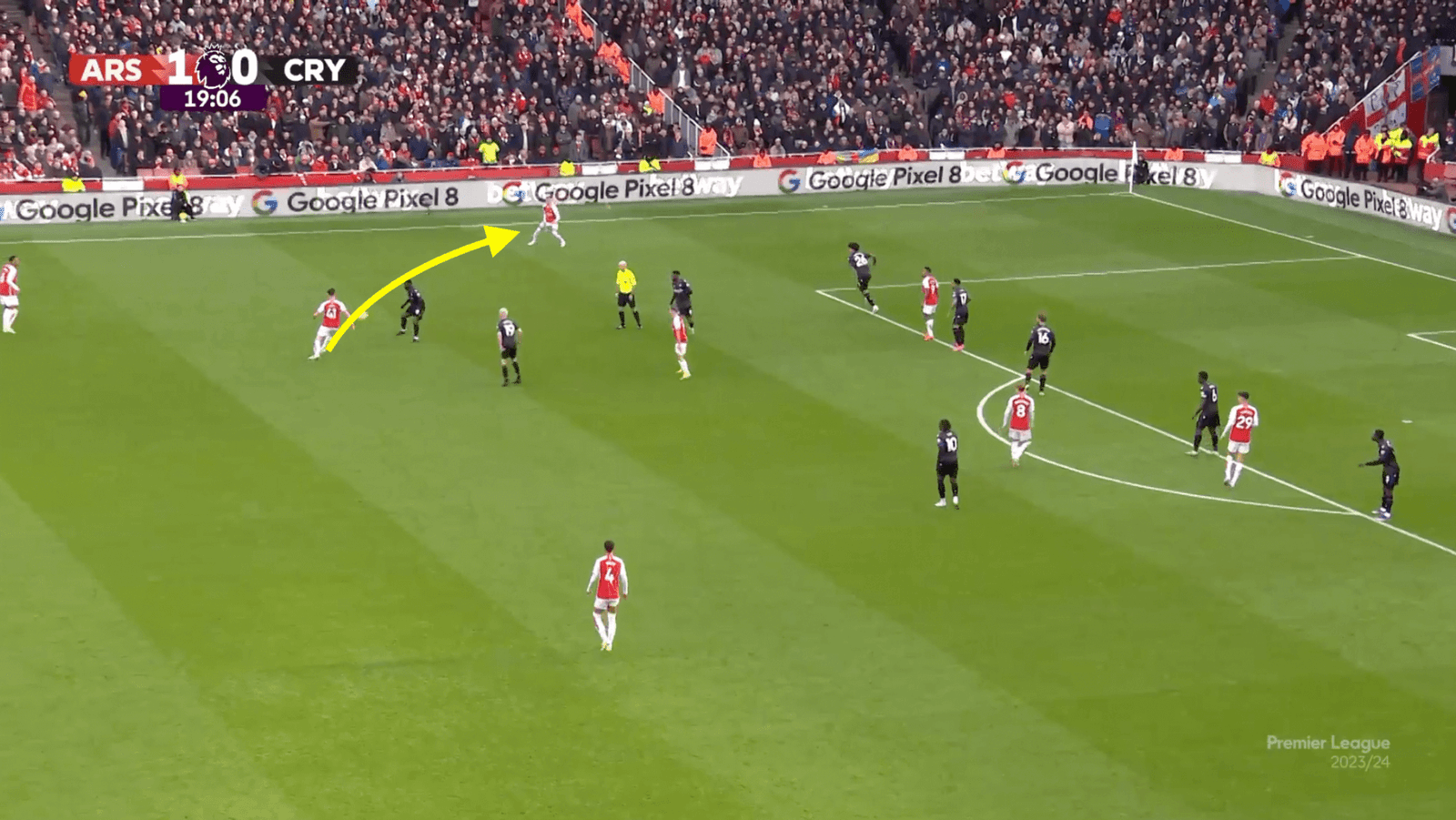

In the example below, Rice reads Crystal Palace’s defensive shift and the angle of Will Hughes’ pressure and decides to step on the ball and send it back to the left rather than receiving it across his body:

When it’s done well, the decision to turn inside instead of across the body happens so quickly, with so little visible difference in how the receiver positions himself, that by the time it happens, the opponent has already curved their pressure to the outside in anticipation of a turn the other way. Routinely receiving the ball with good fundamentals makes it that much more surprising when you switch things up.

That’s how Rodri caught Longstaff off guard to set up a goal against Newcastle.

Receiving across the body on the weak foot

The difference between a great turn and a not-so-great one can come down to comfort. Every player knows the advantages of receiving across the body — better control, wider angles, more options — but whether they choose to do it under pressure depends on what they think they can get away with under the circumstances. It’s about individual abilities and risk tolerance.

Those little personal differences are most visible when a pass arrives from the player’s dominant side, so receiving across the body would mean taking the ball on their weak foot. It’s still possible in that situation to play the next pass on their preferred foot, but if they do, they can’t shield it with their body in the same way. The angles become less natural.

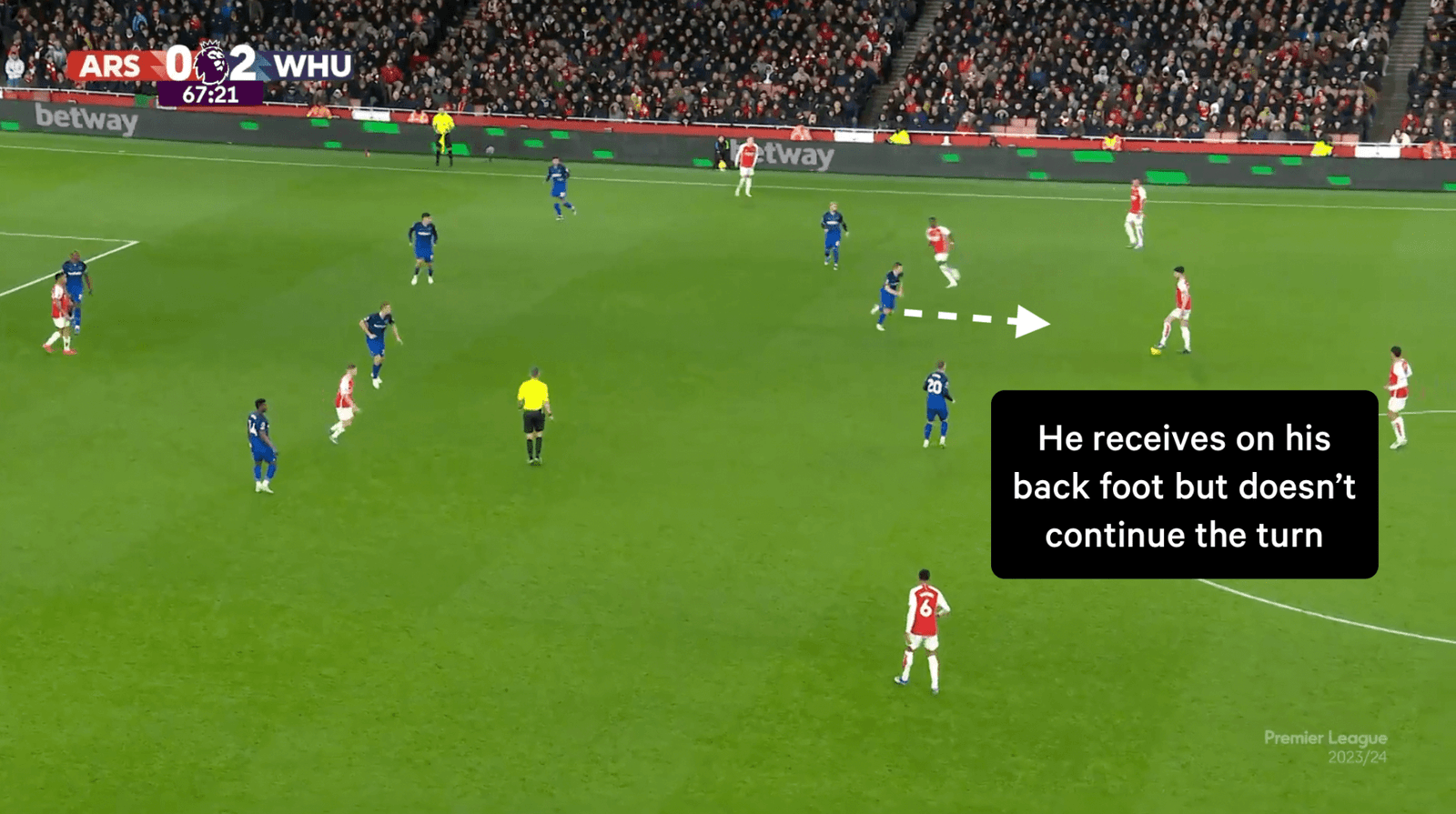

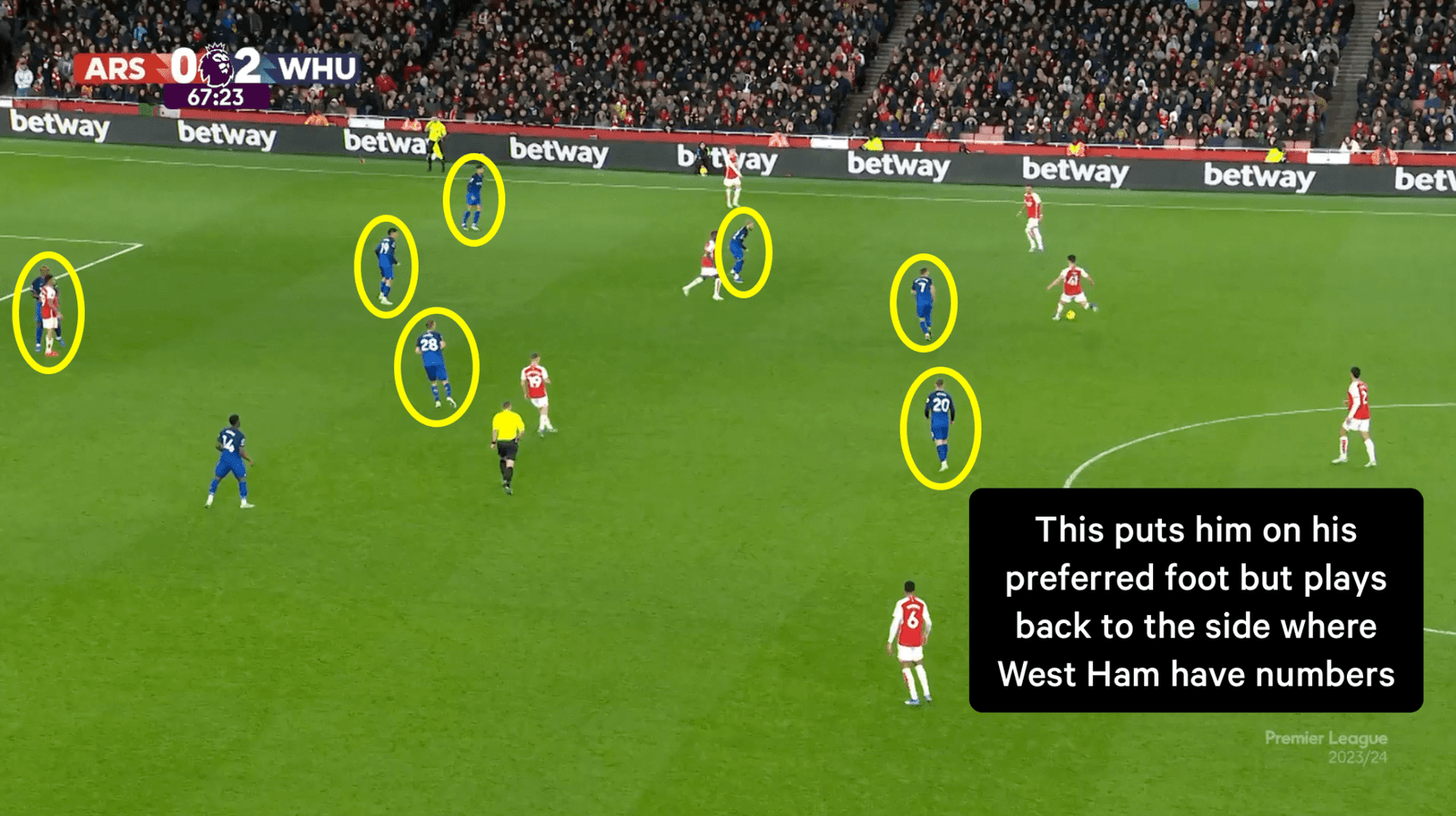

Rice and Rodri are right-footed, but Rice is less comfortable moving from right to left, where a forward pass might require him to use his left foot or the outside of his right boot. When the ball arrives from his right, you’ll frequently see Rice send it back to that side rather than receive it across his body. Even when he does open up to control the ball on his left foot, his next touch may be a change of direction to bring it back onto his favoured right instep.

This isn’t exactly bad — doing the comfortable thing is usually the right choice — but if a pivot isn’t confident receiving across his body, he’ll not only have a hard time playing forward, but he’ll also wind up sending a lot of balls back to the side where the defence already has numbers.

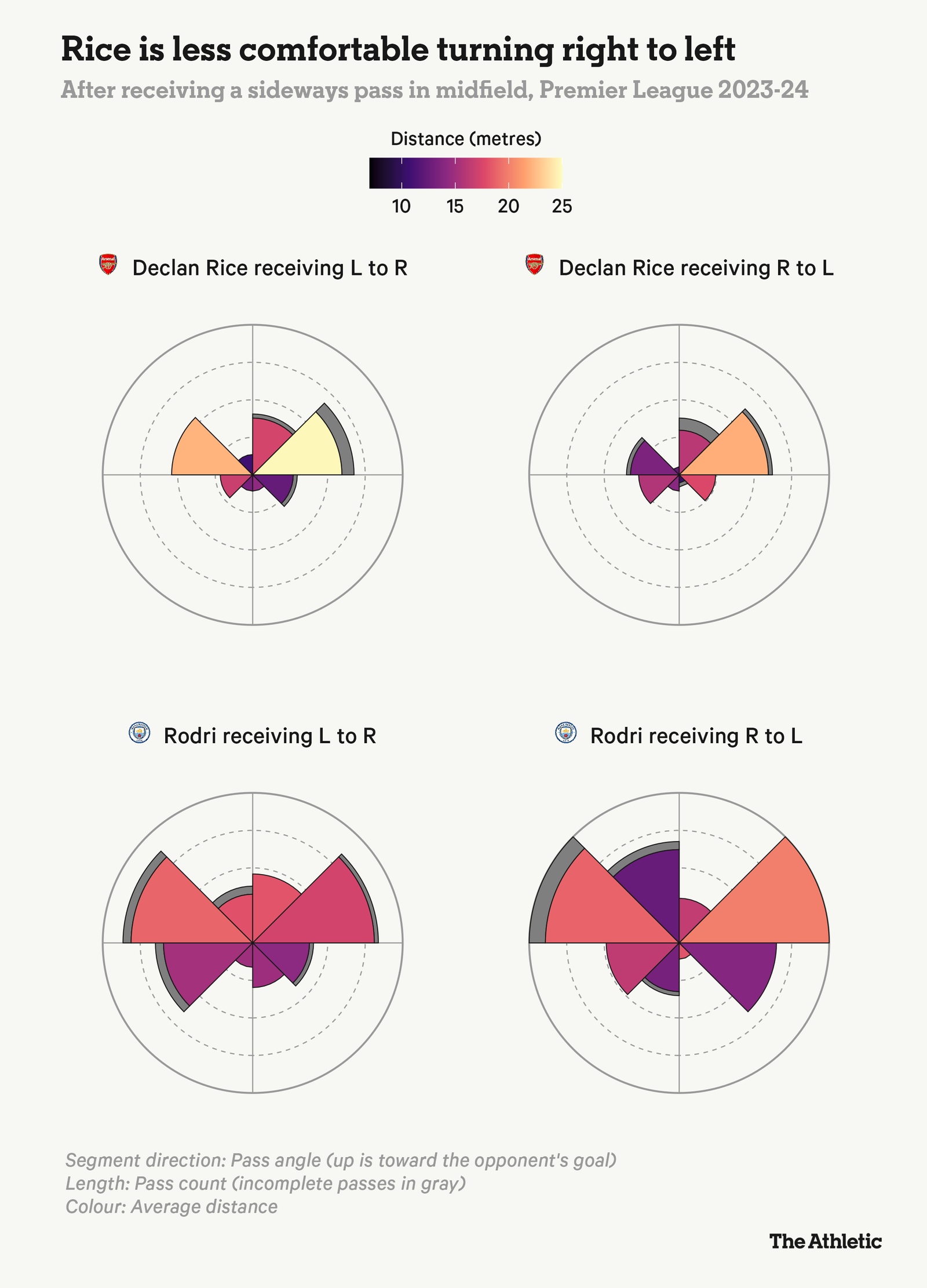

You can spot the difference between Rice and Rodri’s comfort levels in their passing data. The pass sonars below show which direction each tends to play the ball soon after receiving a medium-length sideways pass in midfield (as in all of the example plays we’ve looked at).

When they’re receiving from the left, both players are about equally likely to direct the next pass to the left or the right, but when they receive from the right, when receiving across their body would mean taking the ball on their weaker left foot, Rodri stays versatile and unpredictable, but Rice is much more likely to pass back to the right to avoid making an uncomfortable turn.

The slice of the sonars where you’ll notice the biggest difference is in balls received from the right and played forward to the left — the kind of angle that typically requires a player to receive across the body. Rodri makes this turn regularly, but Rice barely does it at all.

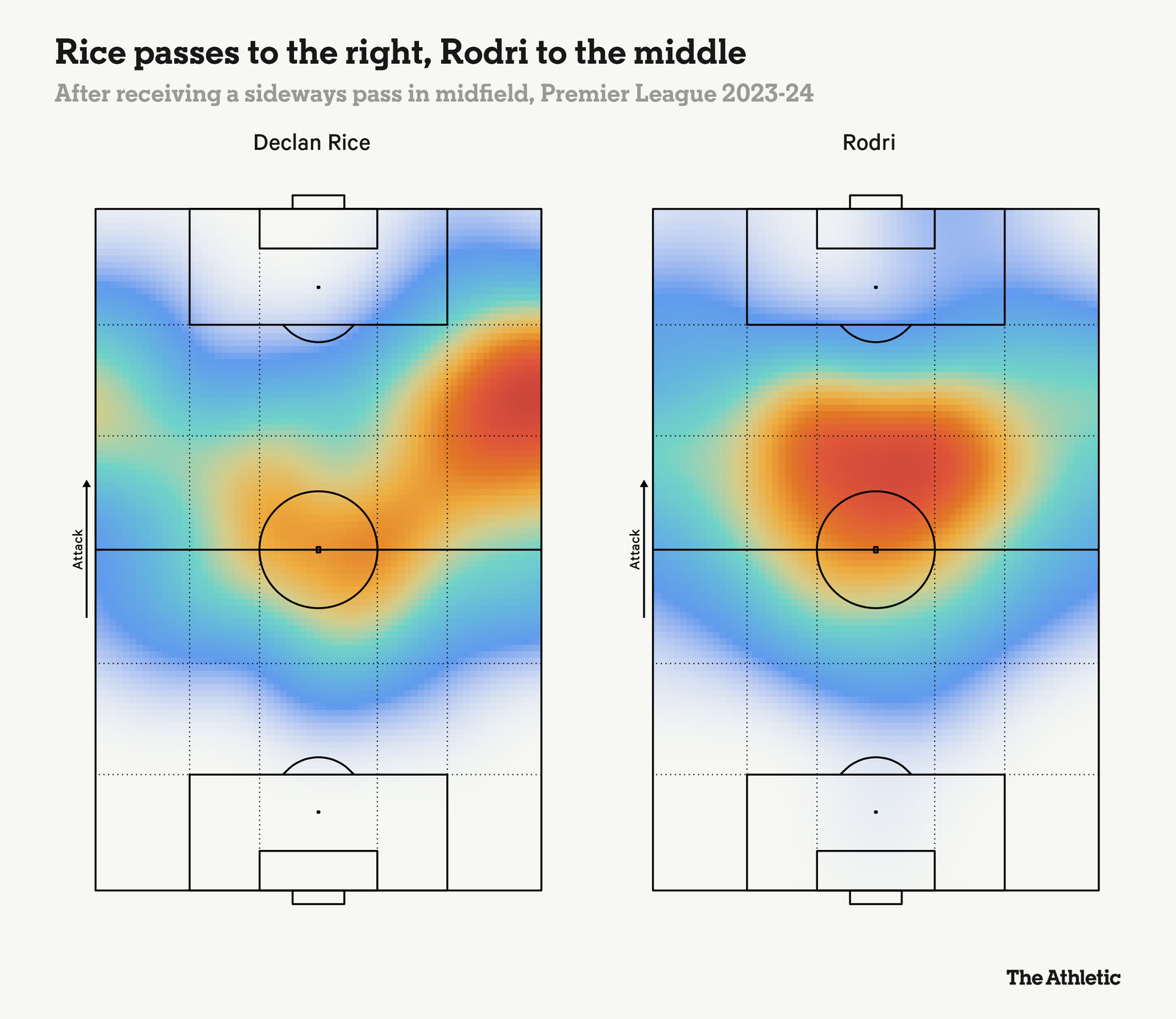

Minor mechanical differences in how a pivot receives the ball can have major effects on how the whole team plays. When you look at the destinations of Rice and Rodri’s circulation-type passes (the same ones captured in the sonars above, where the pivot has just received a short sideways pass in midfield), those differences become glaringly obvious.

Arsenal certainly don’t mind sending a lot of attacks up their right wing, where Bukayo Saka, Martin Odegaard and Ben White can combine to create chances, and Rice does a lot of other things well. In an open game, like the one against Palace over the weekend, none of this ticky-tacky circulation stuff is much of an issue.

But when they’re trying to break through a deeper block, even slight discomfort playing in small midfield spaces can make a difference. Rice’s team-mates don’t look for him on the second line quite as regularly as City play to Rodri, who’s more comfortable turning under pressure. To get on the ball facing play, Rice drops farther away from the opponent, widening the space between Arsenal’s lines and making the centre-backs behind him redundant, while Odegaard wanders outside the lines to compensate. All of this makes it a little bit harder for the team to play up the middle.

A lack of line-breaking passes from midfield into the critical zone at the top of the opponent’s box has played a part in Arsenal’s diminished attack this season. Since signing Rice, they’ve become more reliant on crosses and are creating eight per cent fewer non-penalty expected goals (xG) per game compared to last season (not to mention 14 per cent fewer actual goals, even after the weekend’s romp).

Team-level numbers like that are never down to one player, much less one specific passing situation. They’re the product of a whole squad’s style of play. Style starts from fundamentals, though, and little details like how your defensive midfielder receives and turns in the middle of the pitch can sometimes turn out to be, well, pivotal.

(Top photo design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here