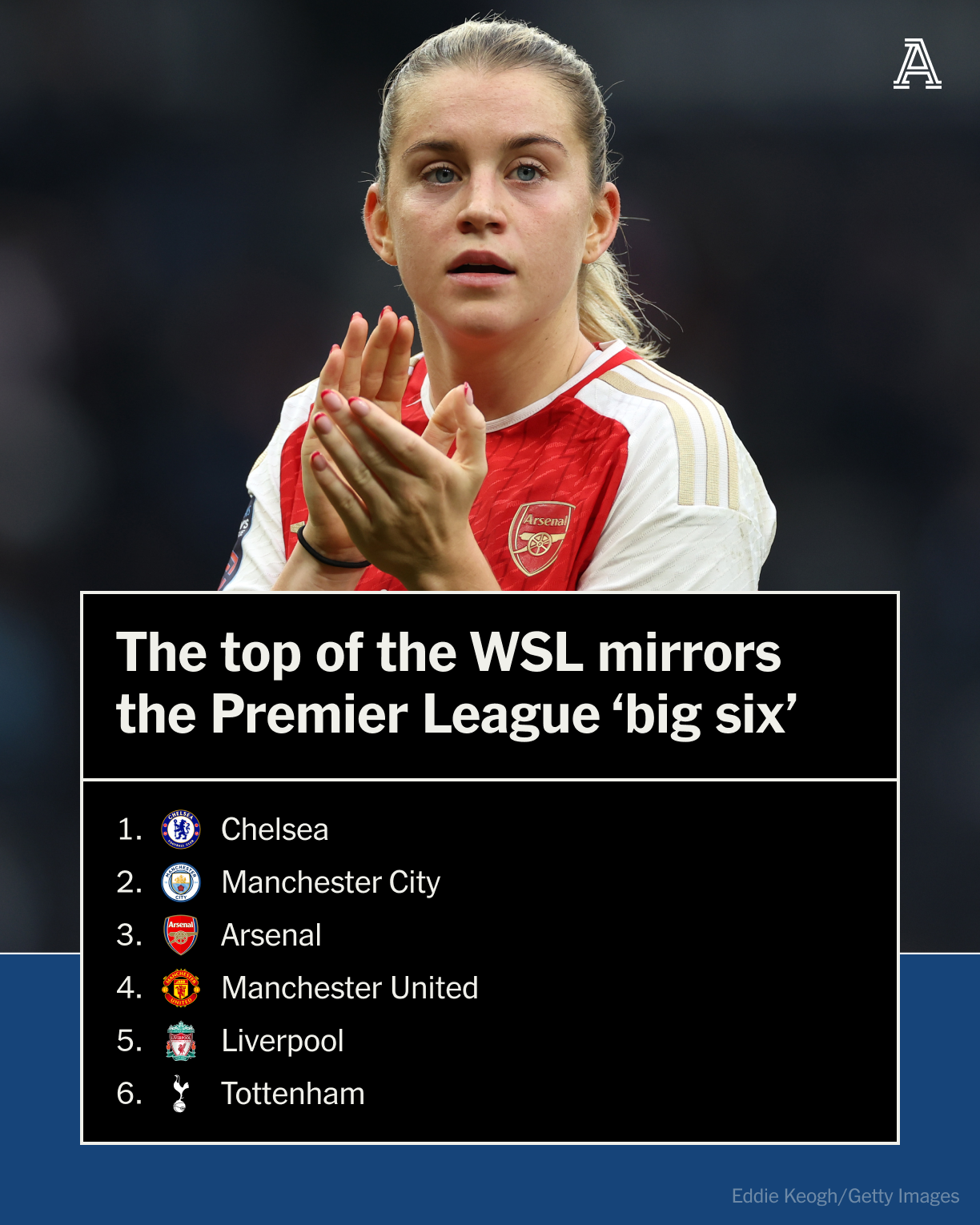

Take a look at the top six places in the Women’s Super League (WSL) table and you could be forgiven for thinking it was the Premier League standings from any point over the past decade.

Chelsea, Manchester City, Arsenal, Manchester United, Liverpool and Tottenham Hotspur — the Premier League’s established ‘Big Six’ — occupy positions one to six in the WSL with seven games remaining. Never before have they all finished in the top six in the same season.

Is that good or bad, exciting or boring? One thing is for sure, it is a far cry from the first WSL season in 2011. Independent sides Doncaster Rovers Belles and Lincoln Ladies were among the eight teams involved. Of the founding members, only Arsenal (2011 league winners), Chelsea (sixth) and Liverpool (eighth) remain in the WSL. Manchester City Women relaunched in 2014, Manchester United in 2018 and Tottenham were renamed Tottenham Hotspur Women in 2019. Top-six finishers in recent years have included Birmingham City and Reading (2018-19), Reading and Everton (2019-20), Everton and Brighton & Hove Albion (2020-21), West Ham United (2021-22), and Aston Villa and Everton (2022-23).

Today, every WSL side is affiliated with a men’s team and the top of the table has a very familiar look to it.

The mirror image of the men’s ‘Big Six’ shows these clubs are investing in their women’s operations. “It’s reflective of whatever investment sits across the table,” says Rehanne Skinner, manager of West Ham, who have slipped down the table in the seasons since their sixth-placed finish in 2021-22. “If you look at the playing budget from top to bottom in the WSL and the Premier League, I would imagine that has a large influence on where people fit within the table. It’s indicative of where the game’s going.”

Rehanne Skinner’s West Ham are 11th this season (Ben Hoskins – The FA/The FA via Getty Images)

Cynically speaking, UEFA licensing requirements state clubs have to invest in women’s football by providing support to an affiliated women’s football team. Furthermore, men’s sides can filter money into their women’s sides and not be affected by profit and sustainability rules (PSR). It is a way of encouraging investment in the women’s game.

Top-six clubs have invested — some significantly earlier and with greater financial force than others — in their women’s teams because they see “positive outcomes for the club”, according to Christina Philippou, principal lecturer in accounting, economics and finance at the University of Portsmouth.

“Traditionally, clubs saw women’s football as a cost: ‘Why should we invest? It’s a drain from the men’s team. We could get all the money we need from the men’s side because of our global branding’.

“The past few years have shown there is potential to make money from women’s football and access demographics and sponsors that are traditionally much more inaccessible for men’s clubs. There are, however, a number of clubs spending money on women’s football who are still incredibly sceptical about women’s football.”

Affiliation with leading men’s teams has certainly benefited the teams at the top of the WSL.

“The top six men’s clubs have the biggest budgets and fan groups,” says Tottenham head coach Robert Vilahamn. “If we’re going to make sure women’s football reaches the sky, it’s necessary it’s the same clubs. You can use all this branding, the staff members around Tottenham, all these spin-off effects that are necessary to get a start on women’s football.

“It’s very important it is the same clubs. It should be a responsibility to make sure we use the strength in the name of a club, branding or money.”

One of the advantages of being affiliated is tapping into shared resources across basic club functions, such as legal, accounting, commercial and marketing.

“The resources are already there, use them,” says Philippou. “Arsenal have done that very well. That’s why we’re seeing the record-breaking crowds. They recognised early the value of women’s football and have used the men’s team’s resources to help grow that side.”

Arsenal Women would not have been able to play at such a large capacity stadium had they not been affiliated with the men’s team. They achieved the highest matchday revenue (£2.6m; $3.4m — 58 per cent of total revenue) among the 15 clubs featured in Deloitte Football Money League (DFML) — the annual profile of the highest revenue-generating clubs in world football — having hosted three WSL games in 2022-23 at the Emirates Stadium.

On the other hand, affiliation means women’s teams will always come second to the men’s teams because the Premier League drives the most revenue and they are therefore the priority. Key clubs’ decision-makers come from the men’s side and so the women’s team is subjected to someone else’s whims, which could stunt growth. This is one of the reasons Michele Kang has made Olympique Lyon Feminine (OLF) a separate entity from the men’s team.

Generally speaking, the success of WSL teams is dependent on the success of their men’s counterparts. Take Reading, for example. When their men’s team were relegated from the Championship in 2023 following a points deduction relating to their financial situation, the club announced they could not commit to the women’s team, who would subsequently go part-time. Everton are another example and, if the men’s team were to go down this season, there would be concern about the impact that might have on the women’s team.

An ever-growing gap between the WSL top four and the rest is emerging — there was a 10-point difference between fourth (Manchester City) and fifth (Aston Villa) last season. Liverpool and Spurs have closed in on the top four this year, but the WSL looks like it is heading in the same direction as the Premier League. Mid-to-bottom-table WSL teams face the same issue as their Premier League counterparts.

“Being too similar to the men’s game can make it start looking like another add-on rather than something in its own right,” says Philippou.

“You need investment, infrastructure… you can only do so much with what you’ve got,” says Aston Villa head coach Carla Ward, whose team are eighth in the WSL. “The top four is night and day to the rest of the league. Anyone who thinks it’s a level playing field is wrong. There’s a massive difference in wages and budgets from top to bottom. The gap probably needs closing. How that happens I’m not sure. It comes down to investment, that’s the reality.”

As the men’s game has proven, an established elite can create problems. Success in the domestic leagues leads to Champions League qualification and financial reward. Those teams will feel they deserve the revenue, but it creates further imbalances domestically. The product needs to be as sellable as possible — the more teams who could potentially win, the more unpredictable and exciting it becomes.

“We’re starting to fall away from that in the WSL,” warns Philippou.

Arsenal striker Vivianne Miedema believes “the league is more competitive this year than it has probably ever been”. “If you invest in your women’s team right now, you’ve got a massive chance of actually catching up with the ‘Big Six’,” she says. “We need to support the other teams, this is the right time to start investing.”

Philippou points to women’s football being a “very young growth market” and that most start-ups make losses in the first few years because of the need to invest in the product and consumer base. “We’ve seen income increase across women’s football, we’ve also seen debt increase,” she says. “That’s OK, but it can’t continue for long, otherwise we’re heading into similar territories as the men’s game.

“A lot of the men’s teams are not in good financial nick and neither are the women’s teams. Football in general has a financial sustainability problem. The new potential independent regular doesn’t cover women’s football, so that could create problems. You could see skewed results because affiliated teams can spend without such strong controls on the women’s game. That’s a potential issue on the horizon. It’s a wait-and-see.”

But there are also issues with limiting investment and spending.

“Any controls you put in place will have a negative impact on the other,” she says. A hard salary cap, an unsuccessful measure used in rugby, may increase competitiveness but negatively affect finances because clubs use the cap as “target practice”, according to Philippou, i.e. spending money they do not have.

It would be wise for women’s football to pick the best combination of controls proven to be successful in other sports to ensure a balance of competitiveness, growth for the game and financial sustainability.

“There’s no easy answer,” she concludes. “We still don’t know what the right thing is but we’ve got a better idea than we did 10 or 20 years ago by looking at the men’s model.”

New structures are starting to crop up in women’s football. Kang has started her multi-club model of women’s teams with the ownership of Washington Spirit, London City Lionesses and OLF, while Mercury 13, a women’s football multi-club ownership group, made their first purchase last week, acquiring a controlling stake in Como Women from Italy’s Serie A.

“There are a lot of different ownership models and ways of running clubs that have worked and a lot that have not,” says Philippou. “More models is potentially a good thing, but the jury is still out.”

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here