Stine Larsen was sitting on the Hacken team bus heading home after a 3-0 win in a Swedish top-flight match. There were three things she knew for sure. The first was she had torn her right anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) for the second time, exactly five years after suffering the same injury.

The second thing was that she would miss the 2023 World Cup and the third was she wanted to have a baby. “I called my fiance on the bus and asked if we should try,” she says. “I would be injured and away from football, so why not see it as an opportunity?”

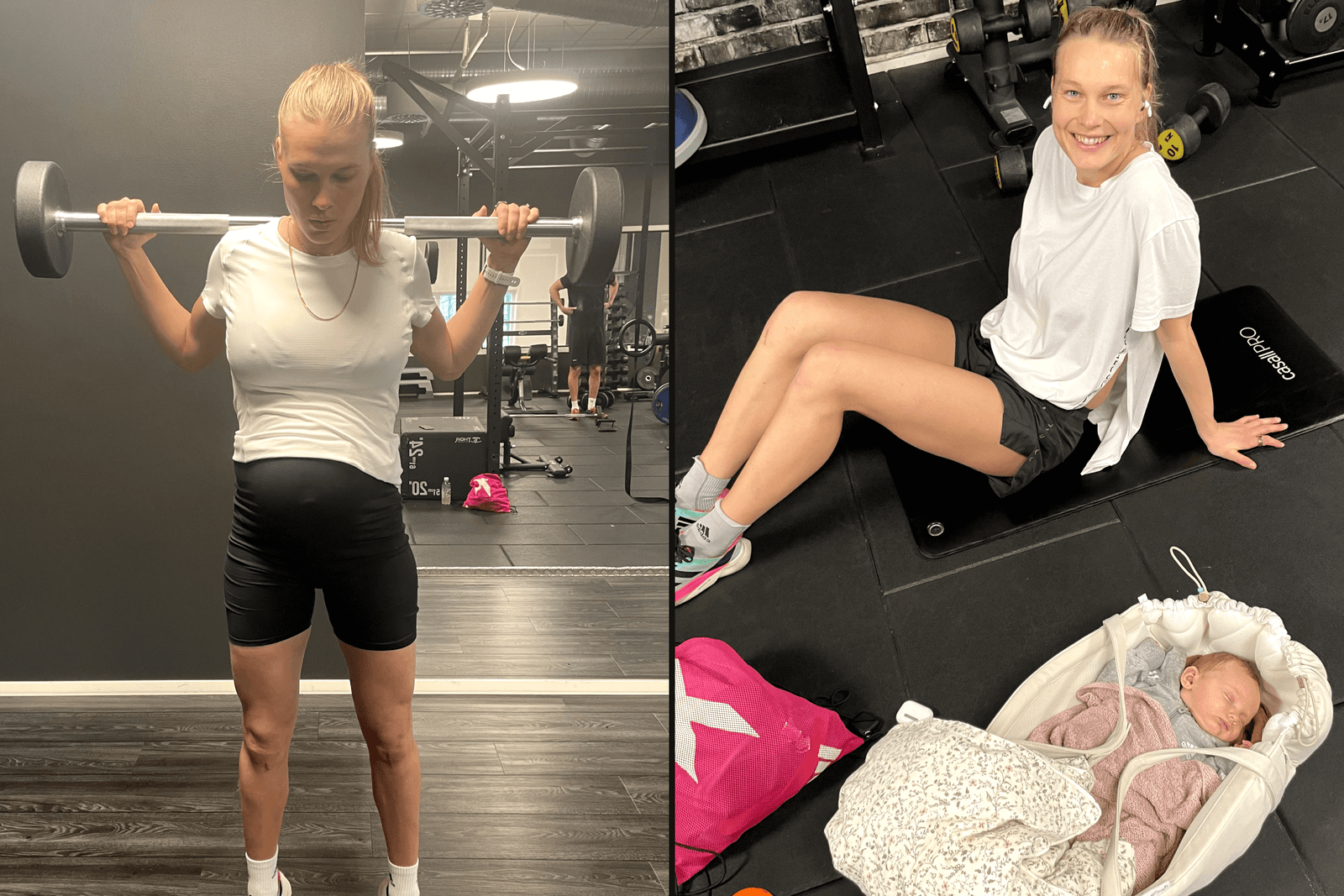

Just over a year later, Larsen, 28, has a four-month-old girl called Lulu and is preparing to return to the pitch having given birth and rehabilitated her ACL. Denmark team-mate Simone Boye recalls Larsen telling her on international camp a few years ago that she envisaged having a baby and returning to football.

At the time Boye, who plays for Swedish side Hammarby, thought, “Well, how would she manage that?” But, four years later, Boye is also pregnant and due to give birth in July. The former Bayern Munich and Arsenal defender always imagined when she had a child it would signal the end of her career.

“You don’t see many other people doing the same,” she says. “It’s hard to imagine you can come back, especially at my age, 32.”

Simone Boye (back left) and Stine Larsen (back second from right) line up for Denmark at Euro 2017 (VI Images/Getty Images)

But internationals including Alex Morgan, Sydney Leroux, Melanie Leupolz, Amel Majri, Toni Duggan and Sara Bjork, as well as other athletes such as Paula Ratcliffe, Serena Williams and Jessica Ennis-Hill, have proved otherwise.

Now Larsen and Boye, who have more than 160 caps for their country between them and started as Denmark’s centre-back pairing on their way to reaching the 2017 European Championship final, want to share their stories as a mother and mother-to-be to address the stigmas that mothers encounter in elite performance environments.

Larsen returned to training with Hacken in May and is targeting her comeback in August after Sweden’s summer break, while Boye still trains as much as she can at Hammarby. Although the two friends have common goals, their journeys are very different.

When Larsen was seven weeks pregnant, the first person she told was Hacken’s manager. But then the club changed coach. “My first chat with him was: ‘Hey, I’m Stine. I’m pregnant’,” she says. The former Aston Villa forward describes that conversation as “weird” but says the club responded well to the news, helped by the fact they had anticipated she would be sidelined for at least nine months with her ACL injury. And yet Larsen still found it hard to tell them. “It felt like a selfish decision that didn’t benefit the club and the team,” she says.

Larsen was fully aware of the challenges ahead. Rehabilitating an ACL while pregnant is not standard practice. She experimented with a knee specialist and continued rehab until two months before giving birth but found being pregnant during the process helped her mentally.

“I was counting the weeks of pregnancy, but I didn’t count anything with my ACL,” she says. “That was not what I had in mind. I looked forward to a good thing instead of being in rehab mode and only thinking, ‘I can’t do this, I can’t do that’.

“It was hard, but I had to progress with my rehab. I also knew, because I was pregnant, I couldn’t just progress all the time, those two curves would cross at some point.”

The Denmark international learned about adjustment, acceptance and listening to her body.

Boye’s decision to have a baby was very different to Larsen’s. She and her partner of eight years, retired footballer Nicolaj Madsen, had been planning for a long time and it formed part of her thinking when she signed a three-and-a-half-year deal with Hammarby in 2022, but it was difficult to find the right moment.

Boye played every minute of Denmark’s four 2023 World Cup games before being knocked out by hosts Australia. She found out she was pregnant with two games left to play in the Damallsvenskan, Sweden’s top division, and went on to win the 2023 title and the Svenska Cupen, the domestic cup.

“It felt like a good time to get pregnant because we just won everything and were going into the winter vacation,” she says.

After the break, at seven weeks pregnant, Boye spoke first to Hammarby coach Pablo Pinones-Arce, then the club director. Even though their reactions were positive and she knew the meeting was going to be fine, “it feels like you’ve done something you’re not allowed to do”, she says.

Sweden use FIFA and FIFPro’s maternity regulations and have added provisions about pregnancy leave, pay, individual training schedules and childcare. Players, for example, will still be paid their full salary after the doctor determines it is too dangerous to play.

Boye, however, who continues to do strength work at the club gym, is the first player at Hammarby to have a child while playing. She has spoken to her team-mates and wondered what would happen if more players within the same team became pregnant within a short period. “It would be harder coming as a number two telling the club, ‘Oh, I’m pregnant as well’.”

Boye wants clubs and agents to have more open conversations about their players’ plans and thinks teams should be aware they will have footballers who become pregnant and that it should not be a “big deal”.

“It’s not beneficial for the club that I’m out for the whole season,” she says. “You always put the club first. Now it’s time to put myself first. The feeling of being a bit selfish is not nice but it’s our lives. If the club can see it as good instead of bad… in my situation, if I had a baby in two years, I would probably have to quit. Now I can play a few more years if everything goes right.”

“Clubs expect injuries, they have squad players,” says Larsen, whose contract expires this winter but who has the option to extend until next summer because she has been pregnant. “You wouldn’t feel bad if you got injured, it’s just bad luck. Then you will do whatever you can to get back on the pitch.” She believes the same approach should be applied to pregnancy.

“It would be good if the club also expects pregnancy so it’s normal and you don’t have to be afraid of that conversation.”

Despite playing for different clubs, about 400km apart, their friendship has helped one another in this next chapter of their lives.

“I have felt things I’ve never felt before,” says Larsen of her pregnancy. “It’s a whole new world and so hard to navigate.”

Seeing Larsen go through her pregnancy has been comforting for Boye. “It’s been so nice to have Stine to share thoughts and experiences,” she says. “You can feel very lonely on your journey. You know people who have been pregnant but not many who are professional footballers.”

Both players say their clubs, as well as their partners, have been supportive, but they want access to knowledge specialised for elite pregnant athletes.

“The club is trying to do everything they can, but the physios and the people around the club haven’t worked with a pregnant player before,” says Boye. “It’s all new for them as well. It’s such a hard time to figure out what is the right thing to do and what are you able to do.”

Both agree there is a knowledge gap around footballers and pregnancy and believe they would have benefitted from having a go-to expert to ask questions like: ‘How long should I run for?’ ‘This doesn’t feel great, is that normal?’ ‘What should I be doing at week X?’.

“A club posted a video of another pregnant player with a big tummy, running around in a passing drill,” says Boye. “I thought, ‘That’s going to be me one month before I give birth’. Unfortunately, I’m not able to do that. It would be nice to hear about people not being able to do everything but still coming out the other side.”

During her pregnancy, Larsen saw physios and doctors and continued to see her dietician and psychologist, with whom she met regularly before becoming pregnant. She had one appointment with a pelvic specialist, provided by the club, but found herself bouncing from the midwife, who lacked bespoke athlete knowledge, to the club doctor, with whom she talked about performance.

“The more cases, the easier it will be to make the right programme for each athlete,” says Larsen, who foresees a specialised service for pregnant footballers. Her experience was, in her words, “good” but also “messy and hard”. “I have done the best I could from the information I had.”

Both players learned that, in the absence of expertise around pregnant footballers, they had to trust themselves.

Larsen did three sessions a week in the period leading up to her due date and completed her last session two days before she gave birth. “My body will tell me what I can and can’t do,” says Larsen. “Here is your programme, test it and adjust along the way. It can be really hard to listen to because it’s so new. It can feel overwhelming.”

Stine Larsen played for Aston Villa during the 2020-21 season and hopes to work her way back into the Denmark squad (Stine Larsen)

Boye nods. “It’s such a hard time to figure out what is the right thing to do. It’s so individual. We could do some drills on the pitch and I would have to say, ‘I need to stop here and then walk for five metres to make the exercise work’. It’s really hard for the physios and coaches to know what’s right.

“It’s so important you speak up and really listen to your body because when I haven’t, it backfires and I can’t do anything the next day. That’s something the club needs to help you with as well. Just because you can’t do something one day doesn’t mean you can’t do it two days later.”

As Boye approaches her July due date, she is realising she can do a little less. She has had some problems with running and, as well as cycling and yoga, has been doing more running in water with a belt around her stomach, much to the amusement of onlookers.

For Boye, a fierce competitor, there was an internal conflict between listening to her body and wanting to push herself. “It took time for me to accept I’m not going to be able to run as much,” she says. “And if I’m running, it’s at such a slow pace that it really doesn’t give me anything. As soon as I accepted I would lose my fitness, I felt much better.”

In May, Boye went into Hammarby three or four times a week, but has also learned to “enjoy the pregnancy”, “take a step back” and “listen to herself”. She also had to accept a more passive role in the team.

Both women say they never felt judged, but there were certain instances when they checked themselves. Larsen remembers wearing the same kit as her team-mates, only hers was a larger men’s shirt. “I felt so weird, being pregnant in a football kit around the team, around athletes. Here I am, a pregnant woman doing gym stuff while they all are looking so strong, fit and fast. That was hard.

“In the end, I was like, ‘Oh s***, I don’t fit in here’. It was easier to be in the public gym because at least I felt like a fit mum or pregnant woman.”

For weeks after Lulu was born in February, Larsen did not think about returning to football. Her focus was adjusting to a “whole new world” and most importantly, sleep. She is managing her postpartum return, which takes into consideration pelvic floor healing, fatigue and adjusting to life and responsibility as a mother.

Larsen gradually picked up her training load, continued her ACL rehab and has returned to individual sessions. She plans to make her comeback at the end of August.

“I feel different in a really good way,” she says. “I don’t think so much, I just have to do things. I have to take care of Lulu, so when I have the time for myself, I have to use that time because that’s what I get. I feel more effective. I don’t question, I don’t think or postpone things, I just have to take action.”

Larsen is intrigued to see if she can keep that perspective on the pitch as she believes it will benefit her. “After giving birth, I would say a Yo-Yo test (similar to a bleep test) is not that hard, so hopefully things will feel easier,” she chuckles.

“I hope to be more present on the pitch and at home. It’s very important that my performance doesn’t define my happiness. I’m so much more than just a football player. Football is important but it’s definitely not the most important thing in life.”

Boye, who has all this to come, muses over whether it will allow her to have a healthier separation from football.

“Sometimes you can be very caught up in football,” she says. “Am I performing? Am I playing? You hear from others that when you have a child, things change. Maybe football is not the most important thing anymore.”

Before Boye became pregnant, she questioned whether she could return to football. Those cited above have dispelled the myth that a player’s career is over after childbirth. Former England international Katie Chapman said it even helped extend her playing days. Competing for a spot in Denmark’s Euro 2025 team could be a target for both players, but Boye is open to the fact she may feel different after giving birth.

“I miss football,” she says. “That’s why I want to get back. But I also know that something more important is coming. My goal is to come back for Hammarby and the national team. I’m just trying to be open to everything. It has to work for my partner and the baby as well. Time will tell.”

(Top photos: Simone Boye and Stine Larsen)

Read the full article here