At Manchester Piccadilly station, a Hemp 11 shirt weaves between the throngs of alighting passengers. Even after the Euros, it feels striking to see a Women’s Super League shirt in the wild; more so when worn by a man in his mid-twenties.

My reaction to the shirt told its own story, reflecting my assumptions about women’s football fandom and the role that men, of all ages, have to play.

The discourse around women’s football focuses so persistently on inspiring young girls, that it often obscures the sport’s appeal to men and boys. A 2023 YouGov poll across 18 international markets found that men are more likely than women to have watched women’s sports in the past month. In Britain specifically, 23 per cent of men watch women’s sports compared to 15 per cent of women.

With that in mind, The Athletic launched its male fans of women’s football survey in December last year to dig a little deeper. We had 4,918 responses submitted over 15 days, and here are the results and the responding comments…

Age of Respondents

| Age | Raw Figure | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

18-24 |

539 |

11 |

|

25-34 |

1,689 |

34.1 |

|

35-44 |

1,305 |

26.6 |

|

45-54 |

820 |

16.7 |

|

55-64 |

417 |

8.5 |

|

65+ |

150 |

3.1 |

Is a ‘one-club mentality’ strategy working?

- 88.7 per cent of male fans consider themselves supporters of a women’s football team

- 8.4 per cent of male fans support a women’s football national team but not a club side

- 73.6 per cent support the same men and women’s team

Since the WSL’s creation in 2011, the game has prized a ‘one-club mentality’ in multiple ways.

With the professionalisation of the WSL ahead of the 2018-19 season, the league moved to a model in which women’s sides required financial support — at least in the medium term — from their men’s teams to compete.

The view persists that this, alongside the England women’s team success (which drives interest at league level), is the most effective marketing strategy. Arsenal have harnessed this, attracting record-breaking crowds to the Emirates consistently. Fans’ willingness to interact with both teams — and the extent to which supporting both is instinctive — is a marker for progress.

The model has its critics in that it favours teams linked to resource-laden Premier League clubs. There are, though, merits when it comes to finding and retaining fans, as our findings show.

- “It was one of my best days when Manchester United announced the women’s team.”

- “The two teams are the same club. I support Arsenal, whether it’s men or women, rather than supporting Arsenal men and Arsenal Women.”

Where a women’s side is poorly supported or of low profile, support does not instantly transfer over from the men’s team. In some cases, this model situates women’s teams as secondary points of interest or offshoots from the ‘main’ attraction.

- “My team Dortmund has a women’s team but they play in the fifth German division. Watching the games is usually impossible.”

- “If New York City FC creates a women’s team, I would get a season ticket. I’m currently following Gotham, in a less convenient location.”

- “As a Liverpool fan, it wasn’t a given that I’d just follow the women’s team — especially when they were mismanaged for so long.”

- “I wouldn’t enjoy supporting West Ham United’s women’s team as they don’t have any England players or high-profile internationals. They’re not putting anywhere near the same emphasis on their women’s team as Arsenal.”

Fandom in women’s football then becomes flexible. Where those ties have not transferred over, fans find teams that align with their values, either morally or in playing style. The profiles and appeal of individual players have a significant role: fans can prioritise supporting a player or use that athlete as a gateway to follow a club more broadly.

Liverpool’s Gemma Bonner takes a selfie with a supporter (David Rawcliffe/Liverpool FC via Getty Images)

Some fans explained that they follow more than one team in the women’s game, or can root for clubs that they would consider rivals in the men’s game.

- “Internationally we have our favourite clubs like Tottenham Hotspur men and Chelsea women, but we also gravitate to our favourite players and U.S. players playing internationally.”

- “I started supporting Chelsea women because of (midfielder) Jessie Fleming. I still support Arsenal men.”

- “I’ve followed Liverpool since I was a child but I follow (Man) United because of my son. We are big Lionesses fans and they have the highest concentration of Lionesses.”

- “Through (Vivianne) Miedema, I became an Arsenal Women supporter but I am a United men’s fan. It is difficult in matches between United and Arsenal — I am not sure who I want to win more.”

Male fans are impacted by the women in their lives

- One in 10 respondents got into the women’s game through their daughters

- Men are six times more likely to get into the women’s game through their sisters than their brothers

- Men are almost twice as likely to get into women’s game because of their fathers compared to their mothers

Furthermore, 14.9 per cent responded that they go to matches with “family” meaning the above figures may be underestimated. Nonetheless, the findings demonstrated that women play a key role in male fans’ relationship with women’s football, in cultivating interest and attending matches.

- “My younger sister and I always played football in the garden and I used to watch her Saturday games. We started following the Lionesses and Arsenal together around 2017 but my interest stepped up after the Euros.”

- “Both my older sisters played soccer growing up, so I began watching at the lower levels. My mom and aunt both played in high school and my grandma is in our local athletic hall of fame for her coaching tenure. The women’s game has always been part of my life.”

- “My wife volunteered at the women’s European Championship in 2022. After the success of the Lionesses, we decided to buy season tickets for Brighton Women.”

- “It never occurred to me not to watch women’s football. I played all my life and married a woman who played with a sister who played professionally and that certainly solidified it.”

This is not highlighted to provoke ire — to reinforce the ‘as a father of daughters’ mentality that women are only valuable when they directly influence men’s experiences — but rather to underscore a vital difference with men’s football.

The social-inclusion charity Football Beyond Borders concluded, in its 2023 ‘Inspiring A Generation?’ report, that men and boys are often the gatekeepers of men’s football fandom. Examining the impact of the Lionesses’ Euros win on inner-city girls, the report outlined how, for most teenage girls, football “feels like something broadly dictated and mediated by men and boys”. It added that teenage girls’ relationship with football often fluctuated “depending on these relationships”.

(Julian Finney – UEFA via Getty Images)

Our findings both invert and endorse this conclusion. On the one hand, this may indicate that girls’ access to football again relates to the interests of their fathers. Alternatively, it could indicate that there is an opportunity for women to dictate the conventions of women’s football fandom — particularly if women are introducing men to the women’s game, as opposed to men being the ones on whom access and acceptance hinge.

There is a culture, too, of men taking their daughters to women’s football as a more accessible or safer introduction to the sport than men’s football.

- “Took my daughter to Socatots when she was nearly four, to do something together. She was a natural. Moved up to a Regional Talent Centre. Noting that some established men’s clubs had women’s teams alongside their RTCs, we would go to watch when we could.”

- “I could take my daughter to women’s football at a much younger age than men’s football.”

- “My daughter’s growing involvement and love for football meant I took more of an interest. She loves the Lionesses and Villa, and I want to support her.”

- “My daughter started playing for a grassroots club and we wanted to watch a match. Arsenal was the best local team and she started playing for their player development programme.”

These intergenerational components of fandom suggest the potential for the women’s game to eventually parallel the men’s, where support for one club (usually local) is passed down through generations.

Statistically, though, the influence of these women was less significant than major tournaments and national teams; more than a third of respondents became acquainted with the women’s game this way.

Attitudes originating from men’s football

- 91.1 per cent of fans followed men’s football before they began following women’s football

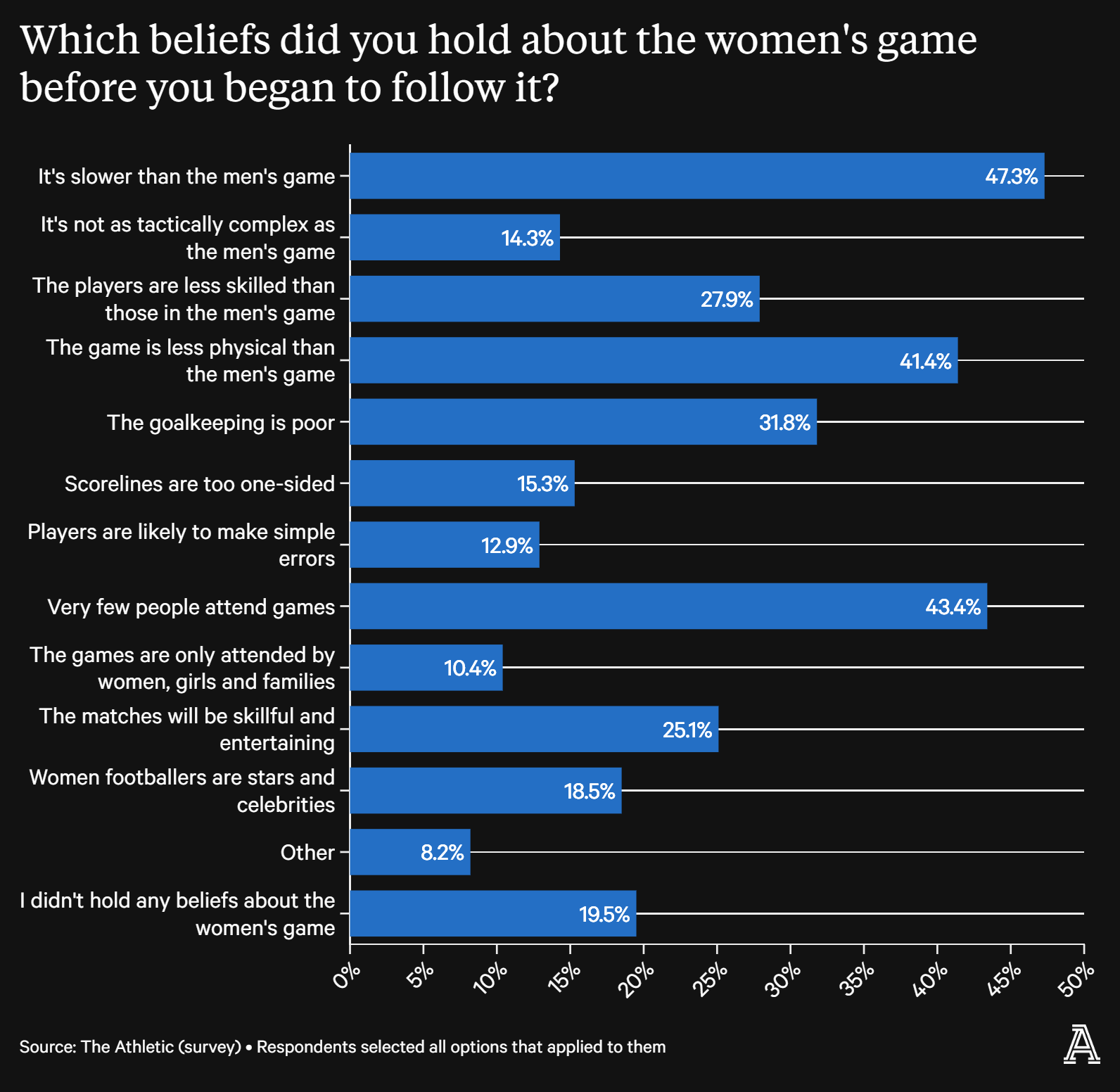

- Only a fifth of respondents didn’t hold any beliefs about the women’s game before they began to watch it

The global dominance of men’s football means it is often regarded — even if subconsciously — as the ‘standard’ form of the game which women’s football is then held against. It then cultivates the belief that women’s football has to ‘win over’ men.

- “Before the 2019 Women’s World Cup, I thought the women’s game was worse technically than the men’s. I also felt the overall play from nation to nation was too similar and a bit boring. After watching that World Cup, I was shocked at the level and technical ability and got hooked.”

- “I held some old-fashioned notions that the women’s game was of a very poor standard, but it’s much better than I thought.”

- “My views came from me being quite ignorant and young — that perhaps it wouldn’t be as entertaining.”

- “The main prejudice I had was that women aren’t as competitive, that the players don’t care as much about winning. This has since been disproven to me.”

Of those who harboured preconceptions about the women’s game, the most common were that:

- It was slower than the men’s game (47.3 per cent)

- Very few people attend the matches (43.4 per cent)

- It was less physical than the men’s game (41.4 per cent)

- The goalkeeping is poor (31.8 per cent)

The most popular two views are not necessarily pejorative. When asked for their views on comparisons between men’s and women’s football, 51.2 per cent said that they “think they are different but neither one is better or worse in any way”. Only 3.9 per cent said that they compare women’s football negatively to men’s football.

- “While the pace is slower, I don’t find that a negative quality. It makes other aspects of the game (tactics, technical execution) more pronounced. I don’t make a direct comparison to men’s football, but enjoy women’s games on their own merit.”

- “The small difference in speed seems to also slightly change the successful tactics, which is interesting.”

Where men felt that they perceived differences, they were keen to add context and emphasise the structural and environmental reasons behind them:

- “When I first took an interest in women’s footy, I firmly felt it was far behind the men’s game but I knew why: the game was only 40 years old after the Football Association (FA) lifted their ban on organised women’s football. Its development had been very slow — (because) it had weak exposure and support.”

- “I did and do believe that men’s pro players are more skilled, but I recognise that this is due to structural reasons. I don’t believe women are less capable. Given the same developmental resources as men, professional women would exhibit comparable levels of skill.”

- “The historical imbalance of, for example, structured training and strength and conditioning coaching for women (as well as the continued pace at which the financial gap between the men and women’s game grows) makes it inevitable that there’ll be a visible ‘standard’ gap. Unfortunately, that’s unlikely to be closed in my lifetime.”

Those who didn’t have any beliefs attributed this primarily to the game’s historic lack of visibility.

- “I didn’t follow women’s football pre-2015 Women’s World Cup because of a lack of coverage in the media. It wasn’t because of a pre-existing belief. At the time, the environment made me think that women’s football didn’t exist.”

- “The extent to which one could hold beliefs about the women’s game in the late 90s was minimal. There wasn’t much of anything.”

That the vast majority of men arrive in women’s football having first been fans of the men’s game did not automatically mean that women’s football remained of secondary importance to them. Of the respondents, 38.8 per cent said that they cared about men’s and women’s football equally, and 19.1 per cent that they cared about women’s football more than men’s.

Morality and advocacy

- An emotional investment in a team or club (79.6 per cent) is the most important aspect of men’s connection to women’s football

- 49.9 per cent said that it was important that players are good role models and 33 per cent that players take social or political stances

- 93.3 per cent said that women’s rights, equality and feminism were important to them

This queries the extent to which women’s football can be separated from its wider social and political implications. When, if ever, will women playing football stop being an act of resistance or protest? And what do we expect of female athletes, as role models, compared to male ones?

The way women’s football is often packaged — alongside extensive pre-match entertainment and meet and greets — can inadvertently suggest that the match by itself is not compelling enough but only 21.6 per cent of men said that interacting with players was important to them.

- “In the last few years, I’ve been privileged to witness live the movement and passing range of (United midfielder) Ella Toone, (Barcelona’s) Keira Walsh controlling a game from midfield, the glorious passing patterns of the Spanish international team, (Lionesses No 1) Mary Earps, a 30-yard thunderbolt by (Tottenham striker) Beth England. How can a football fan not love that?”

- “I felt less attached to Arsenal men’s team post-(Arsene) Wenger so decided to go to a women’s home game in 2018. Had an amazing time and fell back in love with live football. I immediately bought a season ticket.”

Of those questioned, 38.8 per cent said that the fact that there was less money or perceived corruption than in the men’s game was important to them, while 35.5 per cent enjoyed that aspects of the women’s game felt more ‘old-school’ or closer to grassroots football. Remaining that way would likely prevent many women’s players from receiving adequate financial compensation but highlights a particular vision of how these fans want the sport to be.

Only 13.7 per cent followed women’s football because they were disillusioned with the men’s game, but there was a recognition that, at this stage of its development, women’s football can shape itself into a sport that aligns with their moral values. 52.1 per cent said that the safe, friendly atmosphere was important to their enjoyment.

- “Women’s football is inclusive. As a (member of the LGBTQI+ community), I don’t always feel welcome at men’s football. Women’s football is full of out gay players. It feels like a better environment for me.”

- “I see the female players in a more human way; it feels like my mates are playing rather than celebrities. This dynamic is stronger in women’s football and endears the team to me more.”

-

“I don’t follow women’s football because of my disillusion with men’s football but, as time goes on, I find myself more inclined to watch the women’s game. There is less corruption, sports-washing and right-wing politics affecting the game.”

Fans felt it was important that players are good role models, who take social or political stances. Innumerable female footballers have done so already: team protests soundtracked the 2023 World Cup as former USWNT striker Megan Rapinoe’s criticisms of Donald Trump had in 2019.

Rapinoe has been keen to advocate on social and political issues (Meg Oliphant/Getty Images)

But what of the emotional burden this places on female athletes?

- “People often root for or against the USWNT based more on politics than achievement. More liberal folks tend to root for them. Rapinoe and the team as a whole really courted it when Trump was president. This has been part of the appeal to us.”

- “I love the role the women’s players play that is bigger than the 90 minutes. They understand the responsibility to people like my daughter to grow the game. People like Earps and (Leah) Williamson are amazing role models with the extra work they do.”

- “With any male athlete who has a major platform, it feels like it takes a ton of time and pressure for them to say anything about injustice. Meanwhile, the former USWNT captain Becky Sauerbrunn had an editorial in her hometown paper advocating for trans inclusion in sport. It is easy for me to root for the NWSL and USWNT because often the players advocate for social causes I identify with.”

48.2 per cent said that the view that “it is morally right to support women’s football” is important to their connection with the game, and 39.7 per cent said that it was important to them that their support made a difference or was noticed. Within that, some felt a responsibility to act as advocates and ambassadors for the game, in ways big or small.

- “It was not a politically neutral act to exclude systematically half of the population from the ‘national game’. Instead, it was a deliberate choice, underpinned by a particular set of political values. Doing my bit to redress this exclusion fits with my values more than supporting my boyhood club, Nottingham Forest.”

- “I got involved in the women’s game through youth coaching and realised the disparity of support between the male and female game — even at that level. I grew attached to helping grow women’s football.”

What does it all mean?

In England, at least, there has been a tacit understanding that the sport needs male fans and or fans of the men’s game for its financial and commercial health, but not their approval or endorsement to be a legitimate sport.

The women’s game is at a hugely significant juncture in its development, as the ripples of the Lionesses’ Euros win continue to move outwards. The most intense focus has been on changing hearts and minds: on normalising the presence of women and girls in football, to men’s and boys’ eyes as much as girls’ and women’s.

The ultimate aim is for the next generation, raised with female pundits and WSL sticker albums, to never see the women’s game as lesser. In doing so, the women’s game has had to grapple with thornier questions: how can it welcome these fans while preserving the sport’s unique values?

A bigger question is whether this will remain the case for subsequent generations. Will normalising women’s football sever that link? Or will the sport, given its origins, history and current issues around equality, diversity and player safety, always have political layers?

Women’s football is still carving out its own space and working out what it wants to be. But with this infancy comes the opportunity to rewrite what football fandom — so often modelled on the men’s game — looks like. Who should decide that is another question. But men, in various ways, have a crucial role to play.

In part two we will hear from men in more detail about women’s football culture, match habits, what women’s football means to them and the role they play in its fanbase.

(Top photos: Ash Donelon/Manchester United, Alex Pantling/The FA, Alex Burstow/Arsenal FC & Stuart MacFarlane via Getty Images)

Read the full article here