It turns out Murat Yakin wasn’t lying in 2022. He was just one tournament early.

“I think we are the best Switzerland national team that has ever existed,” said their coach prior to the World Cup. He promised their best-ever finish at an international tournament but did not deliver — Portugal beat them 6-1 in the round of 16.

From heartbreak to broken records as, 18 months on, Switzerland knocked out Euro 2020 winners Italy in the round of 16 at Euro 2024. It was only their second knockout win at a major tournament and the first in regulation time (they beat France on penalties in the round of 16 at Euro 2020). It was also their first major-tournament knockout game without Xherdan Shaqiri in the starting XI since the 2006 World Cup.

Shaqiri was the poster boy for a decade, always turning up on the international stage and scoring goal-of-the-tournament contenders. Switzerland have qualified from the group in every tournament since World Cup 2014 but lost five of their six round of 16 games.

There was little in qualifying to suggest this time would be different, and Yakin could count himself fortunate to still be in the role. Switzerland drew five out of 10 games and repeatedly dropped points by conceding late goals, finishing second to Romania. Yakin accepted that they needed to ‘try a few things’. There were frank discussions with captain Granit Xhaka and Yakin changed shape from 4-2-3-1 to 3-4-3.

If national football teams reflect their society, then it makes sense that Switzerland, a multicultural, multiethnic and multilingual country, have so many different tactical components. “We don’t want to change our approach,” said Yakin before facing Italy. “We have made it thus far with our intensity, a solid defence, this shape and our quick counters.”

With England set to play Switzerland in the quarter-finals on Saturday, it’s time to analyse those four elements.

Switzerland’s man-for-man pressing pinned Italy deep — after 25 minutes, Switzerland had 54 final-third passes to Italy’s six. Their 3-4-3 shape suited pressing Italy’s 4-3-3, though Yakin’s side benefited from enforced changes for Italy, with Riccardo Calafiori (suspended) and Federico Dimarco (injured) replaced by Gianluca Mancini and Matteo Darmian (a right-footed left-back) respectively.

Italy were always likely to be right-side heavy in their build-up but Switzerland were as aggressive as they were coordinated in the press.

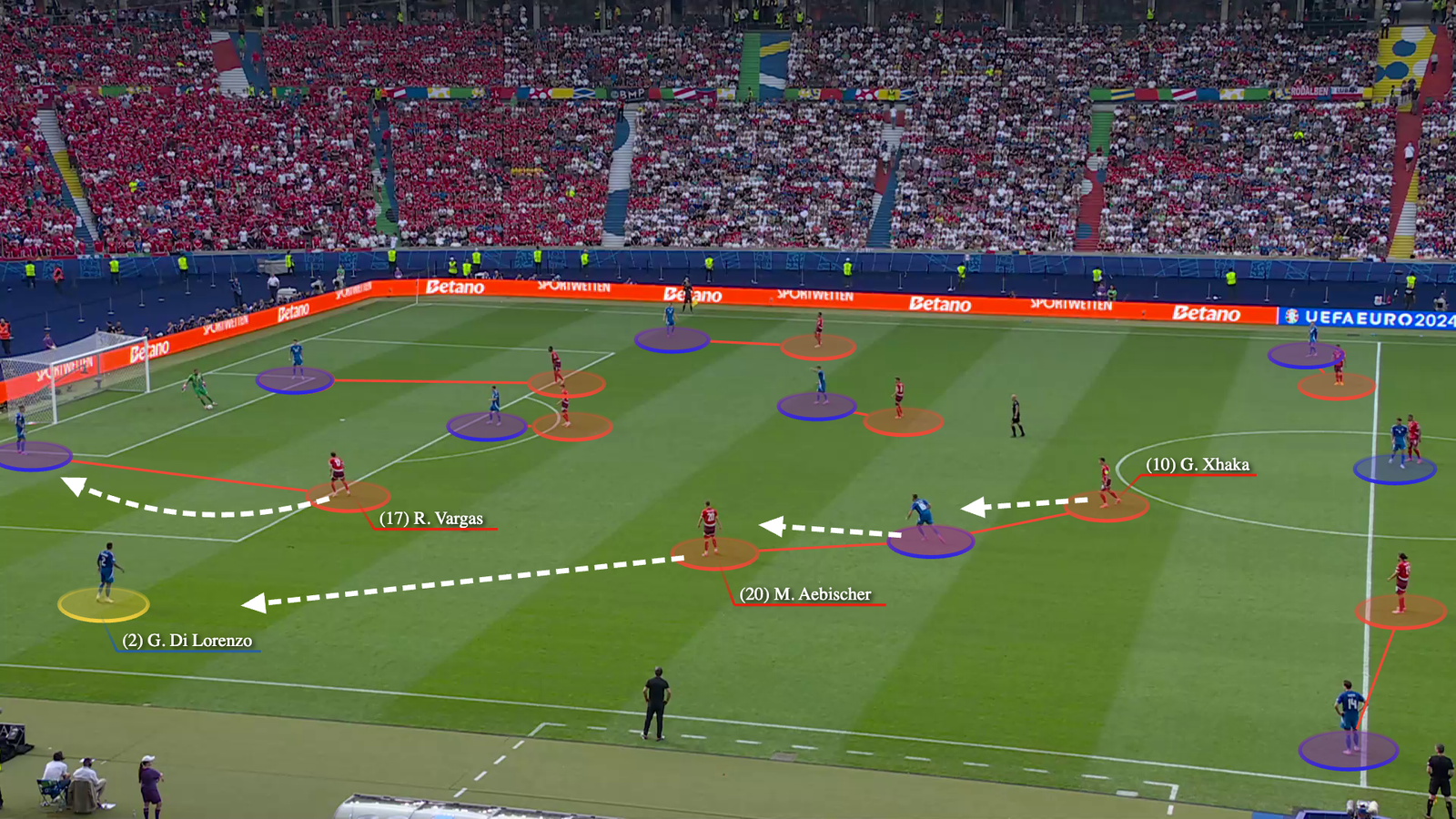

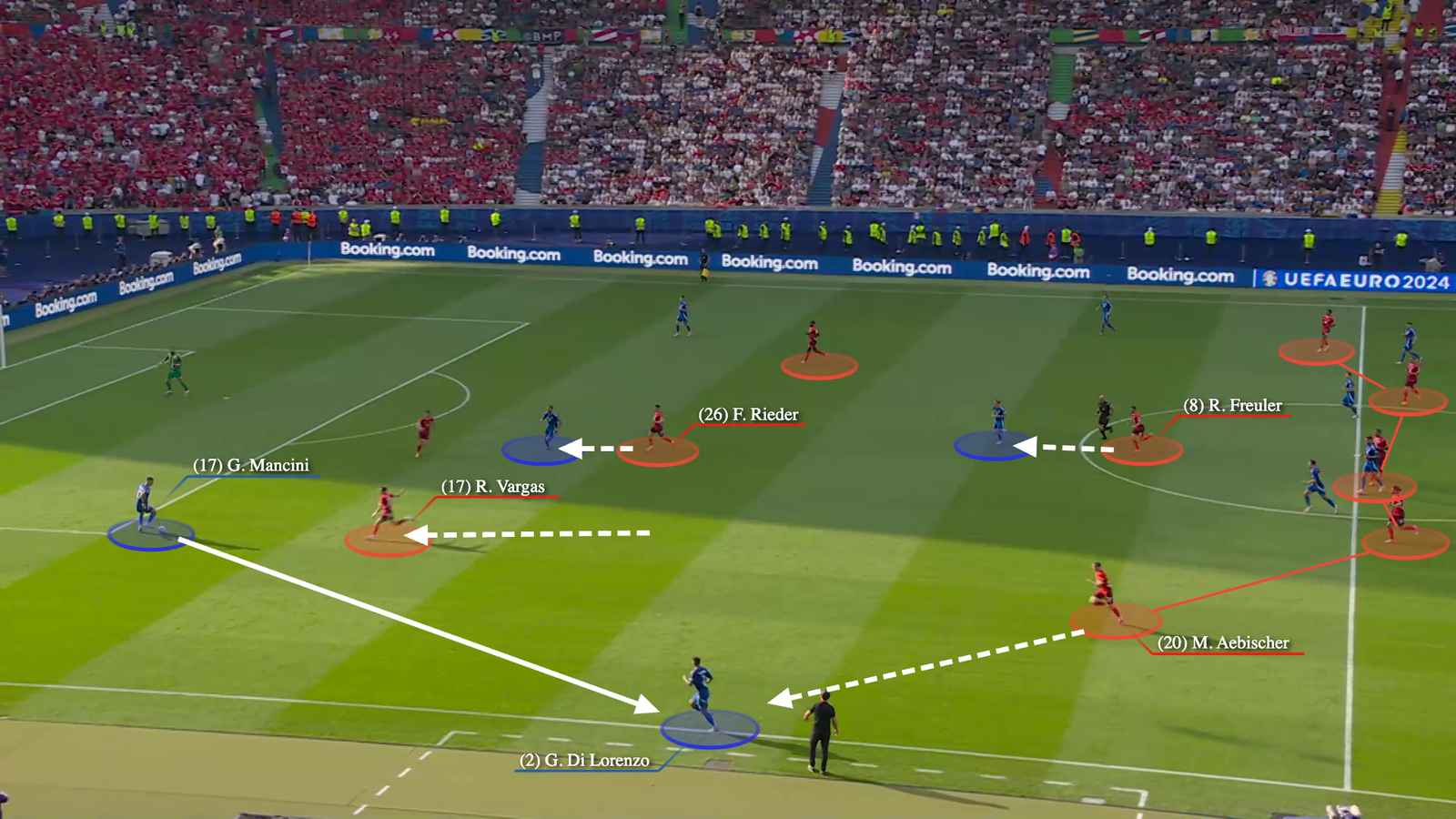

They set a clever trap, initially leaving right-back Giovanni Di Lorenzo unmarked while being much tighter on Italy’s left-back (Darmian) and left winger (Stephan El Shaarawy). When Gianluigi Donnarumma played the ball to right centre-back Mancini, they jumped.

Switzerland’s far-side defender (either their wing-back or No 10) was switched on, coming across onto Italy’s farthest midfielder from the ball. It ensured that the Italians’ central options were marked, leaving the big-switch pass to the winger or full-back open. Theoretically Italy had a three-v-three on halfway, which could be exploited with direct play. However, their wingers held the width, leaving No 9 Gianluca Scamacca outnumbered. Despite his size (6ft 5in), he is not much of an aerial dueller.

Di Lorenzo was frequently boxed in — he had the lowest pass accuracy across Italy’s back four. The first-half was encapsulated by one sequence on 41 minutes, when Switzerland squeezed from a 5-4-1 mid-block to a man-for-man high press. Donnarumma played right, Switzerland’s left side jumped, and Di Lorenzo slipped over, injuring himself and conceding a throw-in. The ball rolled into Yakin’s technical area. He was winning the tactical battle.

“I knew that if the Italians came with a back four, we would destroy them,” said Yakin. “Then we would let them run. Dan (Ndoye) closed down the midfield. El Shaarawy hardly saw a ball.”

Defences notoriously win Championships. Switzerland have only lost once in 18 games since the start of 2023, 1-0 to Romania in qualifying. Yakin built this team on a strong defence — they only conceded twice in eight games in World Cup 2022 qualification.

Italy only registered one shot on target on Saturday: after 72 minutes. The closest they came to scoring was Fabian Schar heading a cross onto his own post.

Playing a back three sets Switzerland up to box defend with a structurally strong 5-4-1. The Italy win was their first clean sheet of the tournament but they never conceded more than once in the group stages, beaten by two headed goals (against Germany and Hungary), and a deflected shot (versus Scotland). It speaks to the experience of individuals and partnerships.

Switzerland’s spine is made up of 2023-24 title-winners: goalkeeper Yann Sommer (Inter Milan, Serie A), central centre-back Manuel Akanji (Manchester City, Premier League) and Xhaka (Bayer Leverkusen, Bundesliga). Yakin’s back three of Ricardo Rodriguez, Akanji and Schar is settled, as is the midfield pivot of Xhaka and Remo Freuler.

Including Sommer, that core six have a combined 558 caps — Italy’s starting XI had 389, for comparison — and seven of the starting XI was the same as the team who lost to Italy in the Euro 2020 group stages.

Particularly in Shaqiri’s absence, Switzerland’s shape is about the sum of its parts rather than incorporating a superstar. Their seven goals have all had a different scorer: the highest number at a Euros (without a repeat scorer) since Portugal in 2008.

Switzerland draw comparisons to multiple club teams. Their central passing combinations, third-man runs and box-crashing No 10s, all of which created their two goals against Italy, are reminiscent of Xhaka’s Leverkusen. A flexible attacking style, sometimes going short and through midfield, other times playing direct to the forwards and hitting switches, has shades of Sommer’s Inter.

Their wing-back rotations, notably Michel Aebischer on the left, who mixes between holding the width and moving centrally to become an extra No 8 in attack, is a trademark of Thiago Motta’s Bologna, where Aebischer and Dan Ndoye (a wing-back/No 10 for Yakin) play.

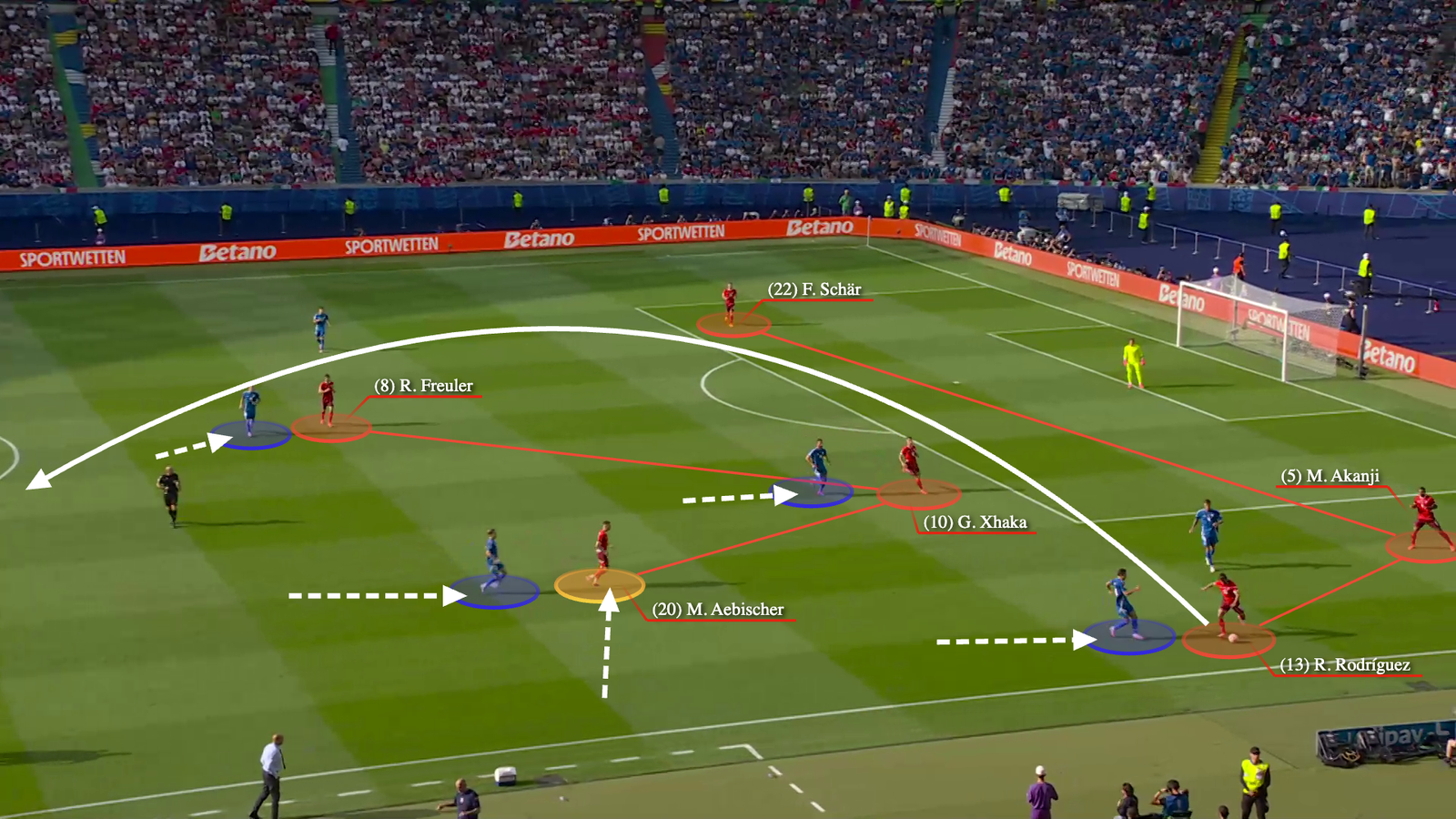

Switzerland’s opener against Italy capped a 31-pass sequence. It highlighted how teams have struggled against their left-sided rotations, as Italy’s central midfielders went tight, which left space for No 9 Breel Embolo to drop in. Akanji split the midfield with a pass into his feet, which Embolo set to No 10 Ndoye. Switzerland are excellent at getting midfield runners beyond the ball, which showed as Ndoye followed his pass wide to Ruben Vargas. Embolo hit the back post.

All this pushed Italy’s back four into their own box and Freuler attacked the space around the penalty spot to score with two touches from Vargas’ pass.

92 – Switzerland completed 470 of 512 passes in their game against Italy – 92% is their best passing accuracy in a game at a major tournament on record (since 1966). Accurate. #SUIITA #EURO2024 pic.twitter.com/zBJxC1Cu8A

— OptaFranz (@OptaFranz) June 29, 2024

There is an easy, unfair narrative that the round of 16 showed Italy’s problems more than Switzerland’s quality. After all, it was the fourth game at the tournament where Italy had conceded first. Even so, Switzerland scored first three times and this was their second opening goal from a flowing passing move.

Kwadwo Duah’s goal on matchday one against Hungary came from a 22-pass sequence. Switzerland played patiently around the 5-4-1 opposition block before working it back into a central position. Hungary’s midfielders failed to lock on. That time, it was Akanji to Aebischer and his through ball set-up Duah (on his full international debut). Hungary head coach Marco Rossi described it a ‘tactical misunderstanding’ afterwards.

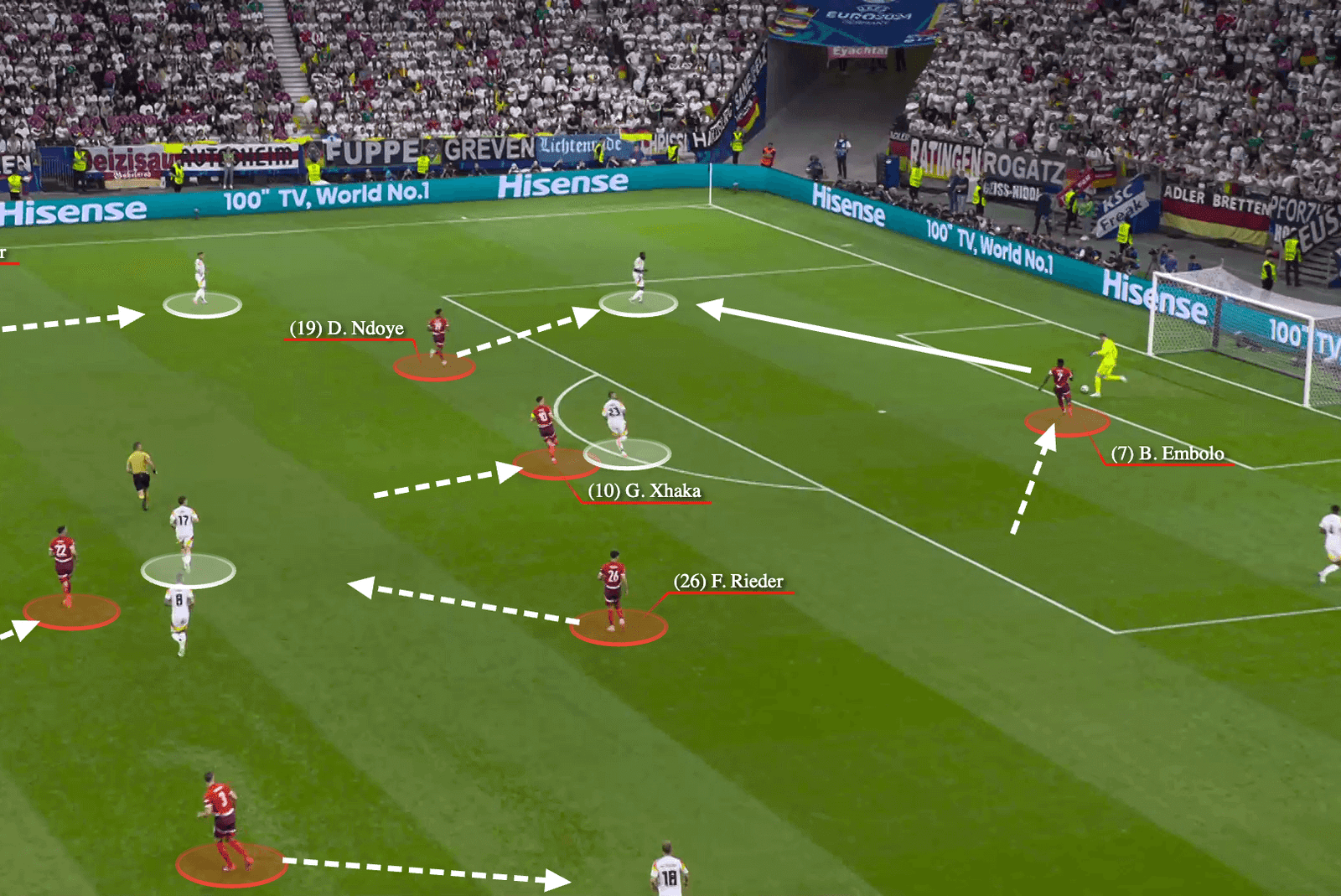

Yakin has his midfielders attack with opposite movements: when one drops in, the other goes in behind. If a wing-back comes inside, the No 10 pulls wide.

That showed for the second goal against Italy. A triangle on the left of Aebischer, Vargas (No 10) and Xhaka exchanged passes. Italy had three defenders out but failed to track Vargas’s run from the wing and in behind Xhaka. Fair enough, he picked out the top-corner and Italy made a mess of the kick-off routine, but it was another slick Swiss move.

Switzerland did not need to show their counter-attacking side in the round of 16.

“We did not only defend as a unit and sit back, we showed we could attack and dominate proceedings,” said Yakin. Straight after their two goals, Switzerland dropped into a 5-4-1 mid-block. Their hybrid approach out-of-possession was synonymous with top Premier League sides, mixing between mid-block defending and man-for-man high pressing.

Switzerland defended similarly in the final group-stage game against Germany — 5-4-1 mid-block, man-for-man high press.

Their 5-4-1 mid-block is perfect to counter-attack from, with wingers and No 10s set to combine and be released. Transitional attacks suit Embolo’s skill set, with the 27-year-old possessing the acceleration and top speed to chase channel balls, and the technical quality to receive passes under pressure, or dribble on his own.

Across Euro 2020 and Euro 2024, only three teams (Denmark, Germany and, ironically, Italy) can better Switzerland’s 25 direct attacks, which Opta define as possessions starting in a team’s own half with at least 50 per cent forward movement — they end with a shot/touch in the opposition box.

There were no big predictions or promises from Yakin at full-time. He allowed himself to bask in the win while remembering to stay grounded.

There was praise for his side for “doing things the right way. “We’ve earned the right to be here but we’re not done yet.,” he said. This might well be Switzerland’s Golden Generation after all. England beware.

Read the full article here