As is customary after a summer of major tournaments, various international managerial jobs are now vacant.

As is customary, the rumour mill has gone into overdrive.

As is customary, there doesn’t appear to be any common theme across the names linked to major jobs.

Take the England job. According to the bookmakers’ odds, the four most likely names are Eddie Howe, Graham Potter, Lee Carsley and Mauricio Pochettino. Two are homegrown managers who have performed solidly at club level. One is the current England Under-21 manager, who has limited club-coaching experience. The other is a foreign manager — albeit one with considerable experience in English football — who has coached major clubs.

Eddie Howe and Graham Potter have both been linked with the vacant England role (Stu Forster/Getty Images)

The apparent contenders for the United States men’s national team job are equally varied. There is a raft of MLS candidates — Jim Curtin, Steve Cherundolo, Wilfried Nancy. Then there is David Wagner, a former U.S. international who hasn’t coached in the country. There is Herve Renard, an international specialist currently coaching the France women’s side at the Olympics. There’s also Thierry Henry, who is doing the equivalent with the France men’s side, and was previously in charge of Monaco and Montreal Impact, but remains primarily a ‘big name’ due to his stellar playing career.

And all this sums up the confusion around international football. There is no obvious model or agreed template on what federations should be looking for.

The summer was a good advert for internal appointments. Lionel Scaloni followed his World Cup success with glory in the Copa America, Luis de la Fuente guided Spain to success at Euro 2024, and Gareth Southgate took England to the final. Other nations, you suspect, might follow suit.

But it’s worth being cautious about those tenures. Southgate offered many qualities as a national team coach in a wider sense, but his lack of tactical acumen was obvious when England faced major opponents in the knockout stage. A manager who had more experience with modern Premier League football might have found more solutions.

Scaloni, meanwhile, has performed excellently as Argentina coach but only managed their under-20s for six friendly games over three months. Julian Alvarez and Giovani Lo Celso featured briefly with the under-20s under him before becoming important parts of the senior side but otherwise, it’s a very different cast. It’s questionable how much Scaloni’s brief experience as a youth coach shaped him.

De la Fuente is a more interesting case, having spent a decade coaching Spain’s under-18, under-19 and under-21 sides before taking the full job 18 months ago. Jorge Vilda, the coach who took the women’s side to World Cup glory last summer, had a similar background. Vilda had no club experience but managed the women’s youth sides before taking the Spain job in 2015.

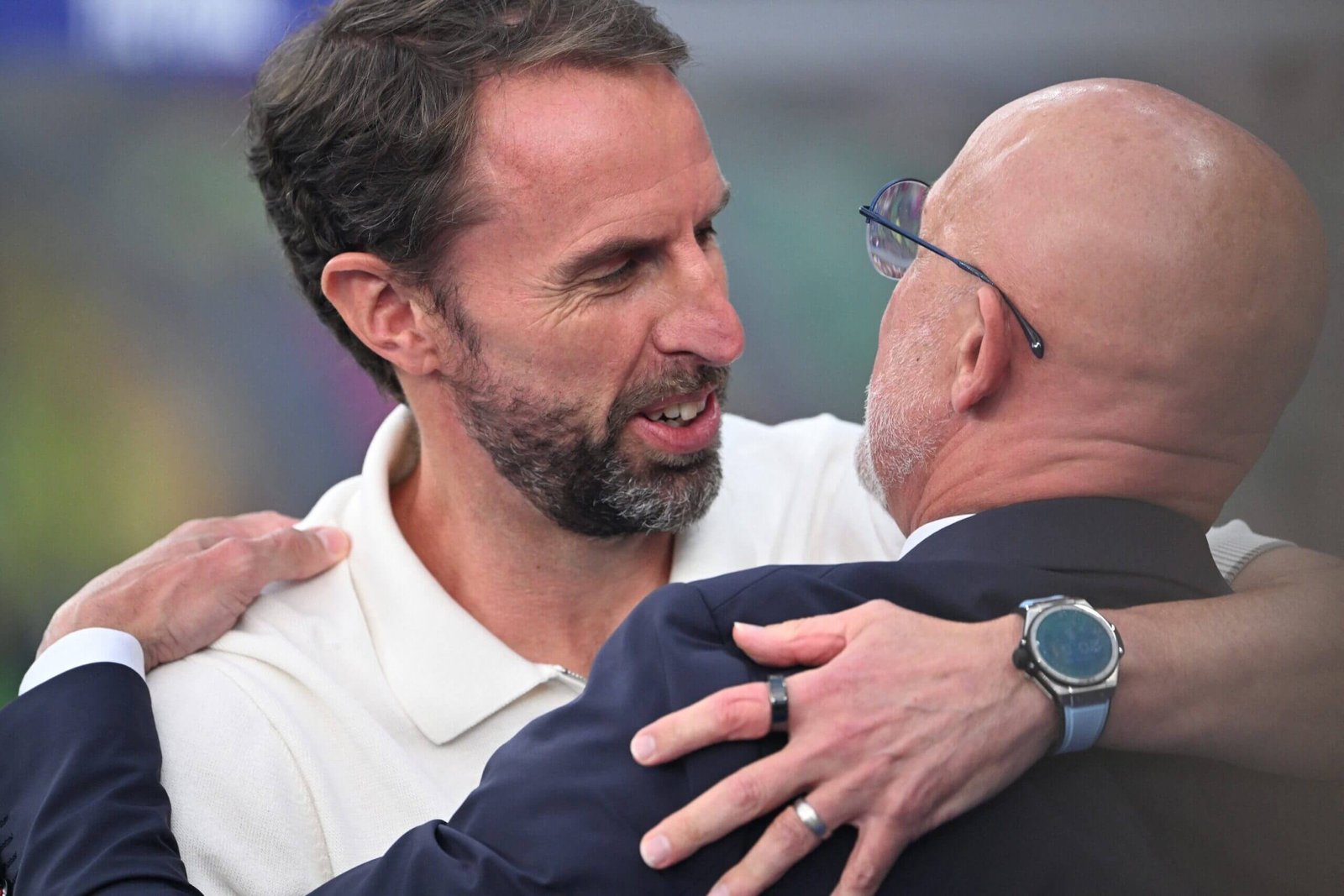

Southgate and De la Fuente are both coaches who rose through the federation scene (Kirill Kudryavtsev / AFP)

Confusingly, Vilda was often at war with his players, several of whom boycotted the national side because of concerns about how Vilda and the Spanish federation treated the squad. Only a few returned for the World Cup success and Vilda was dismissed in the wake of the post-final actions of Luis Rubiales, the federation’s president. It was difficult, therefore, to understand how much credit Vilda deserved. But it’s also fair to concede that his Spain played in a manner familiar from the youth sides.

But what Spain have, more than anything else, is an ‘identity’ — a defined way of playing that means internal appointments make sense. That makes such decisions understandable, logical and — in these cases — successful. There’s an attempt to provide continuity, because of the faith in a winning formula.

The internal appointment is not a new concept. De la Fuente follows Helmut Schon (1972), Jupp Derwall (1980), Michel Hidalgo (1984), Richard Moller Nielsen (1992) and Roger Lemerre (2000) as European Championship-winning managers whose previous employment was also under the respective country’s association, generally as an assistant to their predecessor. Nielsen, for example, was in charge of Denmark Under-21s for over a decade, and also worked as the senior side’s assistant, before becoming the national team coach.

Germany’s World Cup-winning coach Joachim Low in 2014 was also an assistant before taking full responsibility, while the winning coach in 1998, Aime Jacquet, was essentially France’s technical director and then an assistant. His assistant was Lemerre, whose lengthiest coaching spell beforehand was as manager of France’s army side.

Roger Lemerre with current France manager Didier Deschamps in 2000 (Olivier Morin/AFP via Getty Images)

But it’s worth pointing out that various managers who came from club football have also performed well in recent years. Julian Nagelsmann’s impact on Germany this summer in only a short period was obvious, and they could easily have defeated Spain in a quarter-final that felt more like the final. If Germany had scored their chances late on, perhaps we would be speaking about De la Fuente’s tactical naivety in making a major defensive shift midway through the second half.

Similarly, Roberto Mancini guided Italy to Euro 2020 success having spent nearly two decades in club management featuring several league titles. In the semi-final, they defeated an impressive Spain side coached by Luis Enrique, a Champions League winner with Barcelona. His Spain might have fallen short, but were possibly the best side at the competition — only penalties separated Spain and Italy, and indeed Italy and England. Didier Deschamps is another who had won league titles and reached the Champions League final as a club coach, before looking entirely settled as an international boss.

There is probably more awareness than ever that club and international football are fundamentally different, and that the increasingly complex tactics that dominate club football are difficult to replicate at the international level, given the significantly reduced time on the training ground. That said, it is possible to make the reverse argument, that the roles have become more similar. Two decades ago, for example, club managers generally had a much greater input into transfer decisions, whereas now they are increasingly merely the ‘first-team coach’, tasked with roughly the same responsibilities as their international counterparts.

For mid-ranking nations, there’s been an increasing tendency to appoint coaches with previous international experience. The Republic of Ireland’s lengthy managerial search recently ended with the appointment of Heimir Hallgrimsson, who has coached Iceland and Jamaica at continental tournaments. Iceland, meanwhile, are now coached by Age Hareide, formerly of Norway and Denmark. Former Greece, Portugal and Poland manager Fernando Santos has popped up at Azerbaijan.

Heimir Hallgrimsson is the new Republic of Ireland manager (Shauna Clinton/Sportsfile via Getty Images)

In Africa, the German coach Gernot Rohr now finds himself at Benin after stints in charge of Gabon, Niger, Burkina Faso and Nigeria — although in African football, there is a growing feeling that sides need to move away from appointing Europeans with little understanding of a country’s culture and appoint more homegrown coaches. The recent success of Senegal’s Aliou Cisse and Morocco’s Walid Regragui makes that case.

The overriding sense is that there is no obvious model and that the people making the appointment are often rather anonymous. It’s difficult to believe that many England fans know anything about the FA’s technical director John McDermott, but he is the key decision-maker in appointing Southgate’s successor.

This is an era when statistical and technological evolution means there are defined templates for major recruitments, and widely agreed solutions to problems, and a sense that football is becoming closer to being ‘worked out’. But international management remains a glorious mystery, and is all the better for it.

(Top photos: Getty Images)

Read the full article here