Gareth Southgate remained impassive, as he often does. Something had to change if England were going to avoid humiliation. But that change wasn’t coming from him. Not yet.

Writ large on the big screen at the AufSchalke Arena was the scoreline: England 0-1 Slovakia. All that was changing was the digits on the stadium clock. The numbers went up as time slipped away.

To Southgate’s left, along the touchline, a group of substitutes were going through an extensive and increasingly intense warm-up regimen: Cole Palmer, Eberechi Eze, Ivan Toney, Anthony Gordon. They kept looking up, hoping to get the signal. It didn’t come. Not yet.

Other than a goal disallowed for offside — Phil Foden going too early to convert Kieran Trippier’s pass after their first move of real fluency — England didn’t threaten for the first 20 minutes of the second half. They only had three shots, with a total expected goal (xG) value of 0.25.

“It will come,” Southgate must have been thinking. But it wasn’t coming.

Finally, midway through the second half, he activated Plan B. He sent on Palmer, took off Trippier and, in desperation, switched Bukayo Saka from right wing to left-back. More attacking intent, more creativity, more energy… but still not enough. England managed just three more shots, the best of them a speculative Declan Rice effort that hit the post, before the game entered stoppage time.

Plan C didn’t come until the 84th minute: Eze for Kobbie Mainoo. Eze went to the left wing and Foden into a central role behind Harry Kane. Jude Bellingham notionally dropped a little deeper but, by this stage, it was pretty much “anything goes”. With Kyle Walker and Saka pushed up as auxiliary wingers rather than full-backs, it was more 2-3-4-1 than 4-2-3-1.

Still no real threat, though. England dominated the next 10 minutes, forcing a couple of corners, but they didn’t produce a single attempt on goal. And it was at this point, four minutes into the allotted six minutes of stoppage time, that Southgate turned to Plan D, sending on another centre-forward, Ivan Toney, in place of Foden.

Southgate volunteered afterwards that Toney was “pretty disgusted” at being sent on so late. “But what I said to him was, ‘I know this isn’t a good time and I know it’s not how you’d like it’,” the manager said. “But there could be one moment.’”

And there was. Toney didn’t play a direct role in England’s equaliser, which came from Bellingham just 39 seconds later, but Southgate felt the Brentford forward’s presence “unsettled (Slovakia) a bit”.

Toney certainly played a part in the winning goal, redirecting Eze’s shot into the six-yard box for Kane to head home in the first minute of extra time. He performed an important role in extra time, winning headers, holding the ball up and providing a focal point for the attack once Kane’s race was run.

Toney made an impact when he came on against Slovakia (Patrícia de Melo Moreira/AFP via Getty Images)

All’s well that ends well, Southgate suggested. He described the thinking behind the substitutions as “making changes that gave us the best possible chance of scoring, but didn’t leave us completely unbalanced and wide open to counter-attacks”.

In that sense, it worked. England stayed in the game and Southgate didn’t “unbalance” the team until finally he went for broke and it paid off.

But if anything, the outcome heightened criticism of the manager’s use of substitutes. In the eyes of many observers, it was less a vindication than an illustration of what Southgate should have done much earlier to avoid coming so close to elimination: reliant on a Bellingham wonder goal in the fifth minute of stoppage time, which was their first shot on target in the entire game.

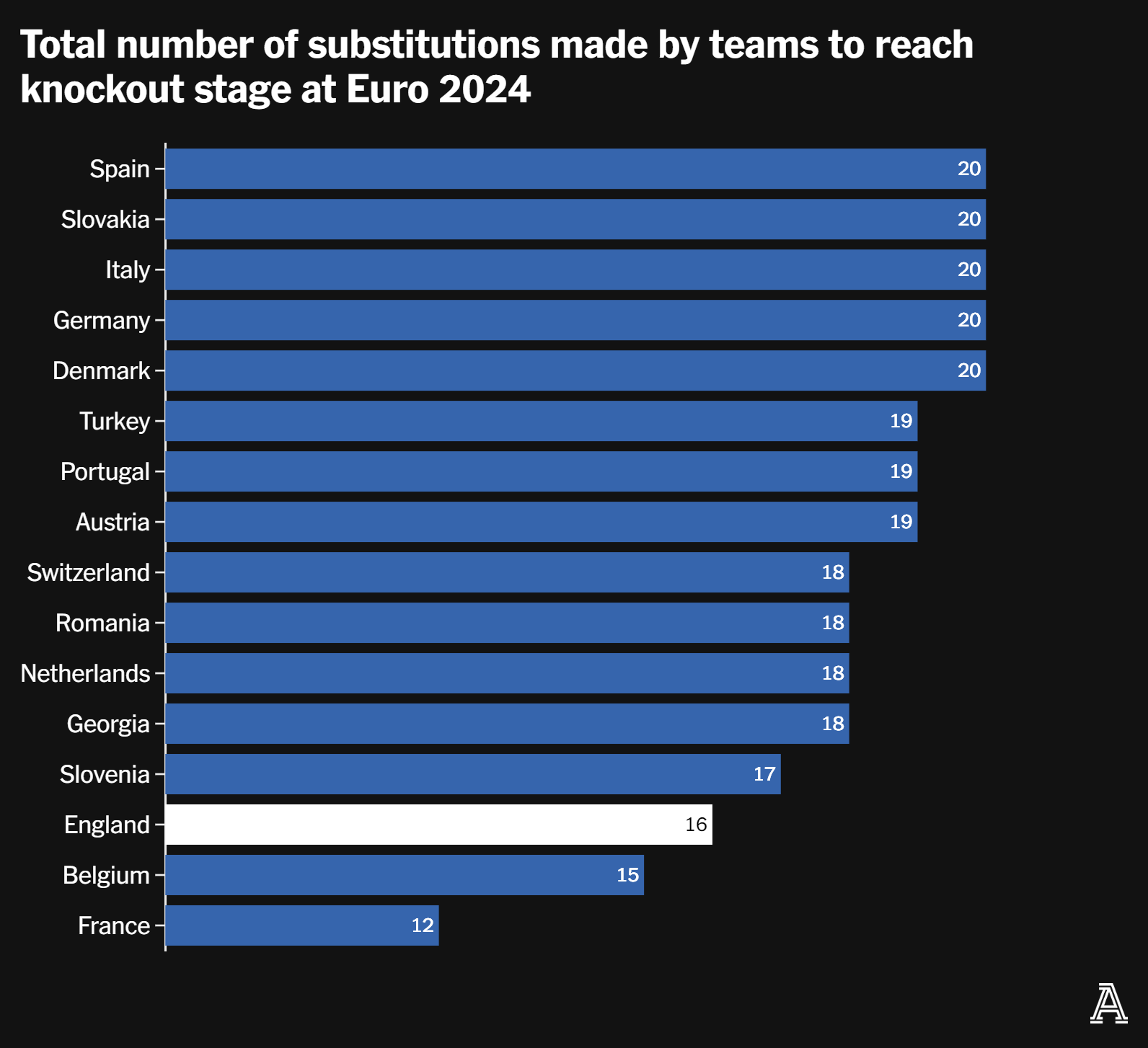

Southgate has made 16 substitutions at Euro 2024 — four fewer than Germany coach Julian Nagelsmann and Spain’s Luis de la Fuente (who have used the maximum five permitted in each game) but four more than France coach Didier Deschamps, whose total of 12 is by far the lowest among the teams who progressed to the round of 16.

Not all substitutions are the same. In an ideal world, a manager would make changes from a position of strength, as, for example, Nagelsmann did in Germany’s opening game against Scotland: replacing Robert Andrich with Pascal Gross at half-time, when 3-0 up, and replacing Florian Wirtz and Kai Havertz with Leroy Sane and Niclas Fullkrug in the 63rd minute.

Southgate has not had that luxury of a two-goal lead at any stage during the tournament. Even their one-goal leads have never looked comfortable. At best, he has been looking for more solidity and energy to retain a leading position (in the closing stages against Serbia and at half-time in extra time against Slovakia). On other occasions, in the draws with Denmark and Slovenia but particularly with those first three subs against Slovakia, he has turned to the bench in desperation while chasing a win.

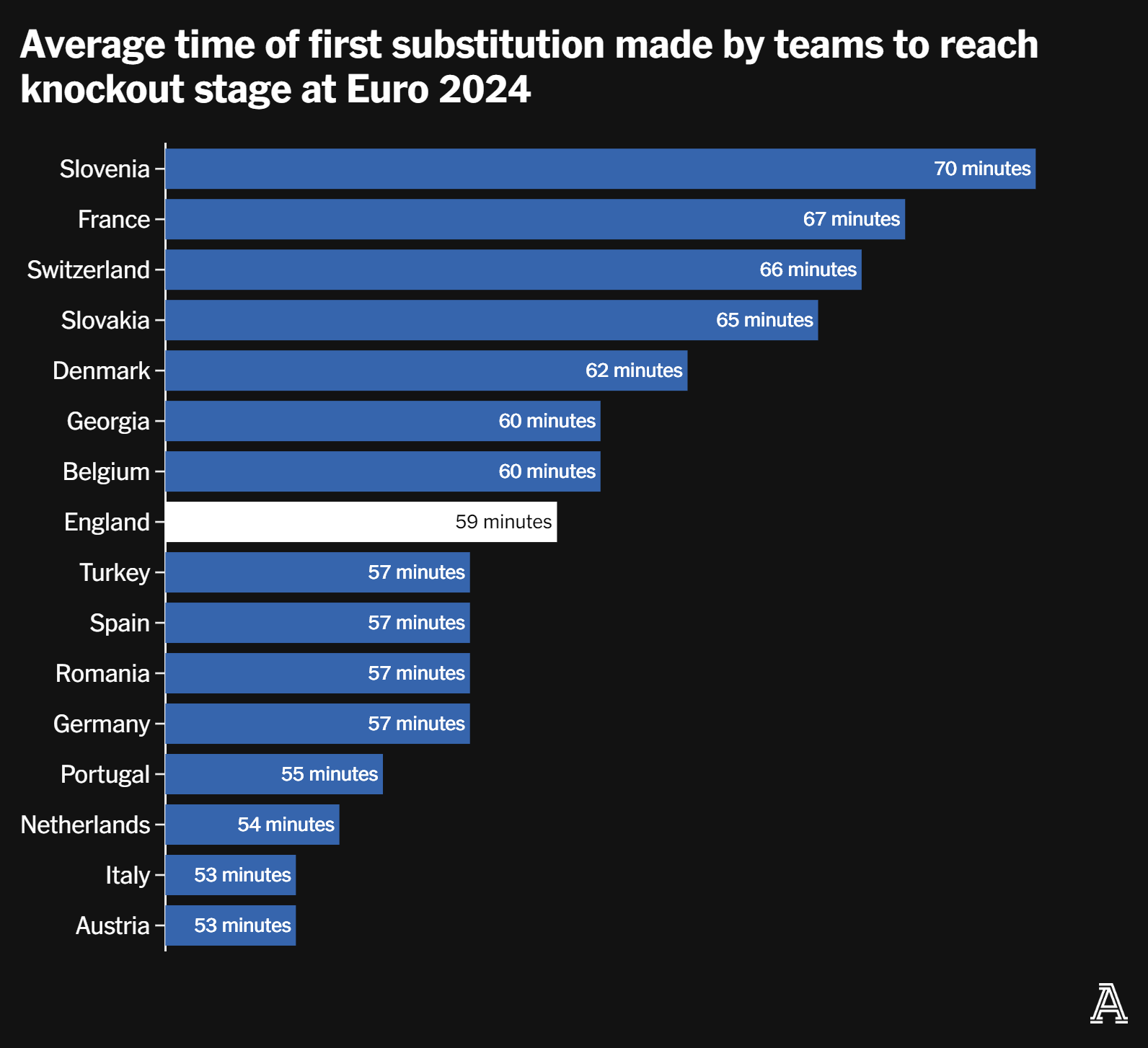

The average time of England’s first substitution at Euro 2024 is the 59th minute. That is in keeping with the average among the 16 teams who reached the knockout stage and the eight teams who have reached the quarter-finals, ranging from the 54th minute (Netherlands) to the 67th minute (France again).

Southgate’s earliest substitution at Euro 2024 came when he replaced Conor Gallagher with Mainoo at half-time against Slovenia. He also replaced Trent Alexander-Arnold with Gallagher nine minutes into the second half against Denmark. Unusually, the game in which England trailed and faced the looming threat of elimination was the one in which Southgate was latest in making both his second substitution (84 minutes) and his third (stoppage time).

In-game management, particularly relating to substitutions, has been the most persistent criticism of Southgate during his time as England manager. It dates back to his tenure’s three most notable defeats: against Croatia in the 2018 World Cup semi-final, Italy in the Euro 2020 final and France in the 2022 World Cup quarter-final.

On the first two of those occasions, the match seemed to have drifted away from England by the time Southgate made changes.

He made just one substitution in normal time against Croatia in 2018, replacing Raheem Sterling with Marcus Rashford at 1-1 on 74 minutes before making three more changes in extra time; he replaced Trippier with Saka in the 70th minute of the Euro 2020 final, three minutes after Italy equalised following a sustained spell of pressure. Former England defender Rio Ferdinand claimed Southgate “froze” on the touchline during that final, not reacting to Italy’s growing dominance until it was too late.

In-game management has been a criticism of Southgate (Franck Fife/AFP via Getty Images)

On other occasions, holding out has served Southgate well. At 0-0 against Germany at Euro 2020, he restricted himself to one substitution, replacing Saka with Jack Grealish on 69 minutes. Grealish played a part in both England’s goals, scored by Sterling on 75 minutes and Kane on 86 minutes.

Grealish for Saka was Southgate’s only change in normal time during the semi-final against Denmark, but the changes he made early in extra time — Jordan Henderson and Foden for Rice and Mason Mount — helped England establish a 2-1 lead before Southgate sent on Trippier for a somewhat miffed Grealish.

But the accusation has been that Southgate is reactive — and insufficiently reactive at that. Waiting until after England had fallen 2-1 down to France in the 2022 World Cup quarter-final, before sending on Mount and Sterling for Henderson and Saka shortly after Olivier Giroud’s 78th-minute goal, fuelled that narrative.

But the intriguing thing about that game against France in Qatar was that Deschamps waited too. For much of the second half, after Kane equalised, England looked the likelier to score. It was Deschamps, rather than Southgate, who appeared to “need” to twist rather than stick. Both kept their cards close to their chest and were finally about to make their first change when Giroud struck.

Deschamps is a fascinating case. He too has been dogged by accusations of inertia on the touchline, waiting until the 75th minute to make changes in the 0-0 draw with the Netherlands in the group stage of Euro 2024 and limiting himself to one change (Randal Kolo Muani for Marcus Thuram) on 62 minutes against Belgium on Monday. It took until the 85th minute for France to break the deadlock when Kolo Muani’s shot was deflected in by Belgium defender Jan Vertonghen.

“We were intelligent. We were playing the waiting game,” Deschamps said afterwards.

But at 2-0 down in the World Cup final against Argentina in 2022, Deschamps made a double substitution as early as the 41st minute (replacing Ousmane Dembele and Giroud with Kolo Muani and Thuram). A second double substitution followed on 71 minutes (Kingsley Coman and Eduardo Camavinga for Antoine Griezmann and Theo Hernandez). Desperate times call for desperate measures. And they very nearly paid off.

Will Southgate be that bold if it comes down to it against Switzerland on Saturday? If things were going terribly, would he go for broke as early in the game as Deschamps did in that World Cup final? Or would he wait as he did against Slovakia in the belief that changing too much would destabilise the team and invite the risk of falling further behind?

The Slovakia experience suggests he would bide his time again. In the ITV Sport studio at half-time during Sunday’s game, Gary Neville described his former England team-mate’s approach to in-game management as “minimum interference” — and said that, in this instance, he simply had to “interfere and rip up the script he’s had all tournament”.

Southgate feels he is more interventionist than this portrayal implies. His first substitution at Euro 2024 has come, on average, nine minutes earlier than it did at the last World Cup. Beyond that, he claimed after the Slovakia game that “pretty much all the changes we’ve made at this tournament have had an impact”.

Eze came on against Slovakia (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images)

There have been positive impacts from the substitutes: Jarrod Bowen set up Kane with a lovely run and cross within a minute of coming on against Serbia; Gallagher made an important tackle to deny Christian Eriksen a clear chance at 1-1 against Denmark; Eze and Ollie Watkins helped energise the attack in the closing stages of the same game; Mainoo, Palmer and (briefly) Gordon brought more energy and verve in the second half against Slovenia; Palmer, Eze and Toney all made significant contributions to the turnaround against Slovakia, while Gallagher and Ezri Konsa brought stability in the second half of extra time.

Eze mentioned earlier in the tournament that Southgate refers to those players outside the starting line-up not as substitutes but as “finishers”, borrowing the terminology of the former England rugby union coach Eddie Jones. It is designed to make those players feel more included and to recognise that the role of a “finisher” is just as important as that of a “starter”.

But for such an ethos to be successful, players need to feel they are trusted, not just used as a last resort. England have lacked energy, rhythm, fluency and control for long periods of every game at Euro 2024, yet Southgate has often resisted change until the need has appeared overwhelming.

For Southgate to watch 84 minutes of fruitless toil against Slovakia before making his second change, and another 10 minutes before making his third, suggested the distinction in the manager’s mind between “starters” and “finishers” might be wider than he has implied.

The Slovakia experience will go down as a near-miss, but as the one that underlined the quality in the squad beyond Southgate’s preferred starters. Mainoo has forced his way into the starting line-up. Palmer, Eze and Toney have enhanced their claims for playing time, whether from the start or the bench. Others, such as Alexander-Arnold, Gallagher, Bowen, Gordon and Watkins, will still feel they can have a say in this tournament.

What seems clear is that Southgate will not rush into changes. It will take something drastic for him to consider “ripping up the script”. By nature, he is someone who sticks rather than twists. There is much to be said for holding your nerve, for resisting the clamour, for backing your judgment, but there will almost certainly come another point in this tournament where Southgate has to gamble — and to act quickly, rather than waiting until it is too late.

(Top photo: Richard Pelham/Getty Images)

Read the full article here