How did you feel watching Portugal the other night? Did you rage at your television as the Cristiano Ronaldo show rolled back into town, with its ageing star still hogging the stage? When he posed in that power stance for the billionth time, puffed out his cheeks and began his run-up — a man who has now scored precisely one goal from 60 free kicks at major tournaments — did you scream, “For god’s sake, give someone else a go!”. Did it look like a parody of his own greatness?

What did you see when he missed that penalty and the tears fell, even as the game was there to be won, his team-mates imploring him to snap out of the personal drama playing in his own head? And what about at the end, as he wrung every ounce from his own performance, when redemption followed and the tears came again? Did you respect his perseverance, or was it pity? Did you tut and think to yourself, “Why is it always about him?”.

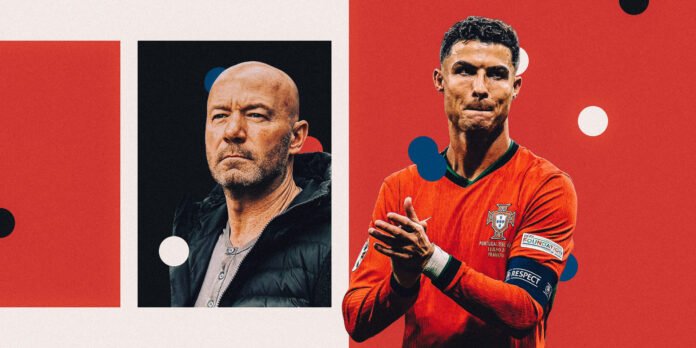

I felt those things, too, or versions of them, but what I saw was something different. I saw a lion; an old lion, yes, battered and bruised and clinging onto his position as the head of the pride by the tips of his claws, unable, or unwilling, to let go.

And, yes, Ronaldo preens and is petulant and he struts and pouts like he always has done and some of that is desperately unappealing, but there is also fragility and beauty in the way he rages against the dusk of his career. There is something magnificent in how the end approaches and the lion turns his back on it.

Ronaldo is railing against the end, which comes to all players (Photo: Xiao Yijiu/Xinhua via Getty Images)

It has been a week for old lions: Andy Murray at Wimbledon, an incredible champion too, straining the stitches in his own back in the hope he can muster one more match, one more taste of it, one more shot; Mark Cavendish, 39 years old like Ronaldo, and now out on his own for most stage wins ever at the Tour de France.

On the one hand, you wonder how and why they keep going. On the other, you’re right beside them, on the court, on the pitch or in the saddle, yearning with them. For the clock to rewind. For one last roar.

Sometimes I provide technical analysis in these columns. Sometimes I do interviews and sometimes it’s about explaining how I feel or think about people or subjects, and I frequently relate to my own experiences in football. It’s not because I’m trying to do a knock-off of Ronaldo and make it all about me, but because I hope to provide some insight into the mindset of top sportspeople.

I’m not comparing myself to Ronaldo either, one of the greatest footballers to have laced up a pair of boots, but I played at the highest level for the whole of my career and, on the subject of confronting sporting mortality, I consider myself an expert. At some point, everybody has to decide when to go, but I understand that balance of playing on versus legacy, feeling inside that you’re still superhuman when the evidence increasingly suggests otherwise.

It all goes so quickly. Over three consecutive seasons with Blackburn Rovers, I scored 31, 34 and 31 goals in the Premier League and it felt like I had sprouted wings. And then, before I knew it, I was getting through games on adrenaline, I’d be out for a meal on a Saturday evening and it would take five minutes to get out of my chair. I’d go for a pee in the middle of the night and hobble and stumble and swear, my back so stiff, my ankle so swollen. Sunday mornings. F***ing hell, they weren’t fun.

In between, I was scoring 20 to 25 goals a season for Newcastle United but serious injuries took their toll. By the end, I was a different player. I didn’t feel different, not in my own brain, but my output was different. I lost pace, so I needed pace in the team around me. I knew where to be, but it took me longer to get there. I could always hold the ball up and always knew how to buy my team time and I became more involved defensively.

Because I was decent at heading and sticking my backside out and being a nuisance, I was having to come back for every set piece. I remember saying to Sir Bobby Robson, our manager, “How come, at my age, I’m having to defend every bloody free kick and every throw-in and corner? Why can’t somebody else do this?”. I suppose I didn’t want football to become a chore. I’d always loved it so much, loved scoring so much.

“He had seen me at my best and now I wasn’t at my best and perhaps he didn’t want the world to witness and judge this lesser incarnation” (Photo: Matthew Lewis/Getty Images)

But then you do what you can for the team, and this would be my big issue with Ronaldo. It will be fascinating to see how Portugal coach Roberto Martinez manages him from now on, because it is like Ronaldo runs the show with their team. He started every group game, even after they had ensured qualification for the knockout stages, and he takes every free kick, even when team-mate Bruno Fernandes has such brilliant technique with them himself.

His movement is still phenomenal, I love his hunger and desire and emotion. It looked like he was on the verge of a breakdown when he missed that penalty in extra time against Slovenia, but then to take his team’s first kick in the shootout… how can you not marvel at that attitude, that courage? Believe me, I get that pressure. Ronaldo has taken standards of fitness and agility to a whole new level, but it’s impossible for him to be as good as he was, and his jumping power and his speed have waned.

The team must come first. He can’t do everything or be everything, which isn’t a coded suggestion that Ronaldo should retire. Only he can come to that decision and great players can always conjure greatness. He’s still got a lot to offer, he’s still a physical specimen and it wouldn’t be much of a surprise if he found a way to outgun Kylian Mbappe and France, who have hardly been fluent in front of goal, in their quarter-final tonight (Friday). But it’s undeniable that he is diminished. It happens to everybody.

It is easy to see Ronaldo is diminished, but it is not easy as a player to accept (Torsten Silz/picture alliance via Getty Images)

It’s bloody hard to face up to the end, particularly at the top of a ruthless sport where you need ego and self-belief to force your way into a team and stay there, to survive and thrive, when you’re surrounded by people feeding that ego and telling you how great you are and when you don’t want it to end in the first place.

In my case, I wanted control, to leave the stage on my terms before people demanded I left it. But recognising that moment is tougher than it sounds.

I had decided to retire at the end of the 2004-05 season. A few people — not many — had told me it was the right time, including Steve Harper, the former Newcastle goalkeeper, and one of my closest pals. We’ve always had that kind of relationship, no bulls*** and unvarnished. He had seen me at my best and now I wasn’t at my best and perhaps he didn’t want the world to witness and judge this lesser incarnation. Harps was looking out for me.

I scored seven league goals in 28 appearances that season. Newcastle finished 14th in the 20-team table, but had done OK in the cups and in Europe and I’d scored a few more there and it all felt a bit… put it this way, you always think there’s a last hurrah lurking somewhere. For weeks and weeks, Graeme Souness, the manager then, had been chipping away at me: “Just one more year, Al. Just give me one more.” He stroked my ego, and my ego purred.

The problem: in football, last hurrahs last 10 months. Graeme had told me I wouldn’t play as much the next season, but that I would be part of the club going forward. If I helped him on the pitch, he could help me off it; there would be games when I might sit alongside him in the dugout, either with the aim of going into the job after him or, if nothing else, learning about management. But I ended up making 41 appearances in all competitions, and Graeme was sacked in the February. It wasn’t the plan.

I was hanging on. My body was a mess, a total wreck.

“I wouldn’t and couldn’t accept that anybody was better than me and that belief kept me going. But I had to drown out the other voice” (Laurence Griffiths/Getty Images)

You have two voices in your head. One is your ego. It’s telling you, “You’re still the best player here”, and I genuinely thought that. I wouldn’t and couldn’t accept that anybody was better than me and that belief kept me going. But I had to drown out the other voice, the one that reminds you about being overtaken in sprint drills, that points out the pain and the aches and niggles. The one that says: “You’re getting in the way now, and they all know it. You’re a bit-part.”

I never wanted that. Getting out of bed in the morning felt like torture and although I wasn’t being asked to train as hard as my team-mates, I hated not being able to do as much as them. Your confidence is like a slow puncture. I didn’t want to be a problem for the dressing room or a problem for the manager if he felt like he had to pick me. I knew my days were numbered, that I was going, going but not quite gone.

I was also lucky. I overtook the great Jackie Milburn as Newcastle’s record goalscorer and reaching that individual milestone took away an itch. It gave me a sense of calm. As I got closer to the end I felt ecstatic. I couldn’t wait. I was so happy.

Ultimately, it came a little sooner than anticipated.

On April 17, Newcastle recovered from a goal down against Sunderland, our local rivals, to win 4-1. I scored the penalty to make it 2-1 and I’ve never experienced pressure like it, not for England in shootouts at big tournaments, not anywhere. Ten minutes later, I was tackled by Julio Arca and my left knee buckled, the pain was a bullet and I just knew straight away.

It all flashed in front of me, from leaving home at 15 to go down to Southampton to make something of myself, to writhing on the turf that day at the Stadium of Light. I remember it so clearly; this is it, that’s me, the very last time I would kick a ball in anger. Yes, I was hurting, but I can’t describe the enormity of my relief. (I came on for a couple of minutes in my testimonial match the following month but could barely move because my knee was so knackered. I was done, over and out.)

The relief I’m talking about was physical more than anything; no more struggling to get up, no more gym, no more pre-seasons, which I’d always hated, and perhaps a bit less agony. There was every other emotion, too, including sadness. And there was a big thought locked away in a corner of my brain that I couldn’t quite bring myself to unlock. If I’d always lived for goals, which I had, then what do I live for now?

My relief lasted three months and then I was craving football. It hit me one morning in mid-August, when the 2006-07 Premier League started. It was like flicking a switch. It was, ‘What am I doing now? Why am I getting out of bed, other than to take the kids to school? Do I go to the gym? Why?’.

Everything I’d known from the age of 15 was gone. I had to find a different kick, because the thing you crave, the thing you love, being the best, all that adulation, the rush of scoring, is gone and it’s never coming back. The quicker you can wrap your head around that the better, but it can take you to some dark places. So I can understand the compulsion to put it off for another day, another month, another season.

Everybody’s different, and perhaps Ronaldo will go on playing for another five years, and fair play if he does. I’m sure he doesn’t want to be a joke, to be the subject of mocking memes on social media (there were a few decent ones the other day, mind), but you can also tell he is pushing to shape and carve his own terms, to insist on a moment of his choosing. I can’t do anything other than admire that, even as I yell at him to let Fernandes take a bloody free kick for once.

Even lions can’t outpace their shadows, but I love the way Ronaldo turns and looks at his and shrugs and pouts and shakes his head. And then turns his back and runs on.

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here