Group stages used to be a cakewalk for Belgium.

They won all three group games at the 2014 World Cup, 2018 World Cup and Euro 2020. Italy beat them in their opening game at Euro 2016 but Belgium bounced back to finish second.

The golden generation that played in those tournaments, managed by Roberto Martinez, notoriously peaked in the groups — they were third-best in the world in 2018 but never reached a final.

If the new-look, new-era team under Domenico Tedesco are going to do better, significant tactical improvements are required.

In terms of results, Euro 2024 has so far been identical to the 2022 World Cup, when Belgium failed to qualify for the knockouts with one win, one draw and one loss. Belgium qualifying second in their group this time around was less due to their brilliance and more the quirk of everyone in Group E finishing on four points — their punishment for failing to beat Ukraine is a round-of-16 tie against France on the much harder side of the draw.

After three group-stage games, it feels like similar problems under a different head coach.

Belgium have been wasteful again (only scoring one of eight big chances; the same as in the 2022 World Cup group stage). Their build-up is highly structured in their own half: a 4-2-3-1 where the midfield pivots play close to the back four and the wingers stay high and wide.

Belgium’s build-up success relies on individual brilliance more than well-executed patterns.

Under pressure, centre-backs and full-backs send long passes into No 9 Romelu Lukaku and, when they stick, they get out. One of their key out-balls this tournament has been into left-winger Jeremy Doku on the halfway line, receiving back-to-goal with a full-back on him. When he is able to turn off his first touch and dribble out, Belgium quickly switch the point of attack.

Tedesco is (unapologetically) building this attack around Lukaku. He only took a squad of 25 with just two strikers (Lois Openda is their other option to Lukaku). He “did not see the necessity” for a third. Lukaku’s international goalscoring record is as good as they come but he offers a very specific No 9 profile: occupying defenders, finishing one-touch in the box and is the target for long passes to set midfielders or wingers.

Euro 2024 is shaping up to be the tournament of the big No 9 but Belgium are unique in that most teams bring theirs off the bench for a striker with a more mixed style. Instead, Tedesco has tried to change the personnel, roles and system around Lukaku.

There were three different winger combinations in the groups: Leandro Trossard left and Jeremy Doku right against Slovenia; Doku left and Dodi Lukebakio right in the Romania win and Trossard and Doku again versus Ukraine — but on opposite sides to the Slovenia match.

The game in which things really clicked was the 2-0 win over Romania.

Belgium still built up in a 4-2-3-1 in their own half. Most of the game was played further upfield as Tedesco’s side shapeshifted into the 3-4-3 shape that was synonymous with Martinez. Right-winger Lukebakio moved inside to become a second No 10 and right-back Timothy Castagne pushed onto the last line.

Here is how that looked. It caused Romania’s left side all sorts of issues as they were defending in a 4-1-4-1, and were unsure which of the full-back and left midfielder should go with Castagne, and which with Lukebakio.

Belgium counter-pressed with intensity and had the ideal structure to circulate around the block, plus two No 10s to make penetrative runs in behind.

“We were able to find (Youri) Tielemans and (Amadou) Onana more than in the first game,” said Kevin De Bruyne afterwards.

“When they’ve got the ball at their feet, it means Dodi (Lukebakio) has more space to come into the middle. (It puts the) numbers up with a four-v-three. Finding those spaces, we were able to create chances. Sometimes, it’s complicated. There are pros and cons of every formation and we know what the risks are.”

By overloading the last line, Belgium stretched Romania, which made space for De Bruyne and the midfielders to play — see Tielemans opening the scoring after 73 seconds, a goal following a trademark pass into Lukaku’s feet, which he set back for a first-time finish.

However, playing aggressively with full-backs is too risky for Tedesco’s liking.

His prioritisation of control showed in the final group-stage game against Ukraine, having De Bruyne take corners short at the end, fearful that one cross might be intercepted and Belgium concede a counter-attack. Belgium had 60 per cent possession but were outcrossed (10 v nine) by Ukraine, such was their hyper-focus on slipped, short passes into the box.

Tedesco’s first-choice back four is remarkably settled but also very defensive: Rennes centre-back Arthur Theate at left-back, Jan Vertonghen and Wout Faes in the middle, and Castagne at right-back. There is a blend of experience and youth, plus two left-footers on the left. There is not much in the way of attacking output.

A lack of full-back over/underlaps becomes a problem because opponents can then double up on Belgium’s wingers: Doku especially. Against Ukraine, Trossard spent a lot of the game rolling inside but Castagne rarely ran beyond him. Tedesco put the poor performance down to “a little bit of everything”.

The Ukraine game underlined Belgium’s progress and flaws under Tedesco. “The press was good at the beginning,” said De Bruyne. “Then, afterwards, we didn’t manage to get the midfield working. It wasn’t so easy, when you’re up against five defenders, to press high.

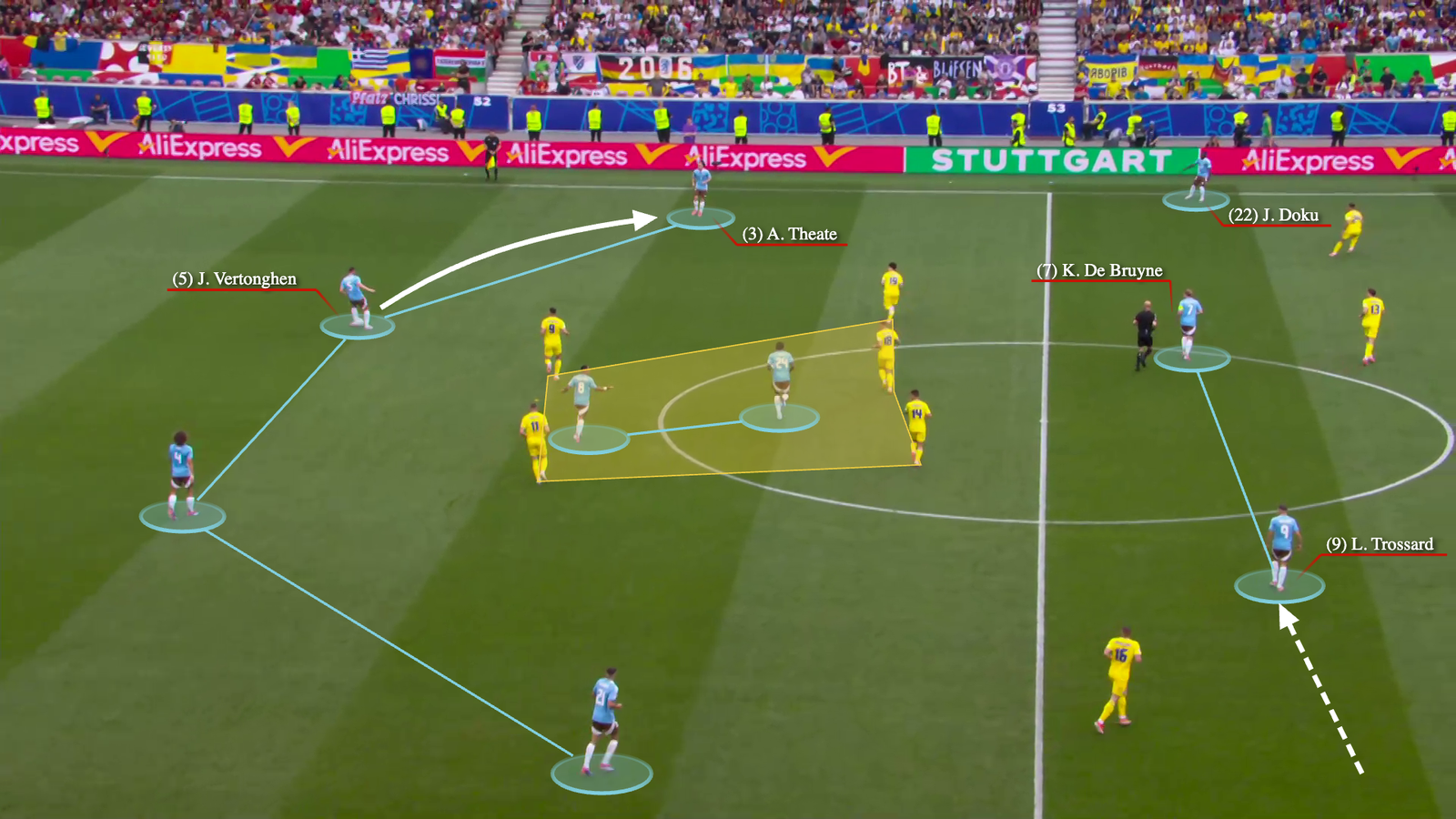

Ukraine switching from 4-3-3 to 5-3-2 indicated they were playing for a point, but Tedesco is all about being tactically adaptable. Belgium continued their aggressive lop-sided press, where Doku moves alongside Lukaku to pressurise the defence, which means Theate jumps to press the full/wing-back while midfielders lock on.

Here, De Bruyne forces a misplaced pass, which Theate intercepts.

Belgium’s pressing has significantly improved under Tedesco.

He is known to change their out-of-possession plan and shape during games if things are not to the required level. Belgium made over three times as many final-third regains this group stage (21) as at the 2022 World Cup (six).

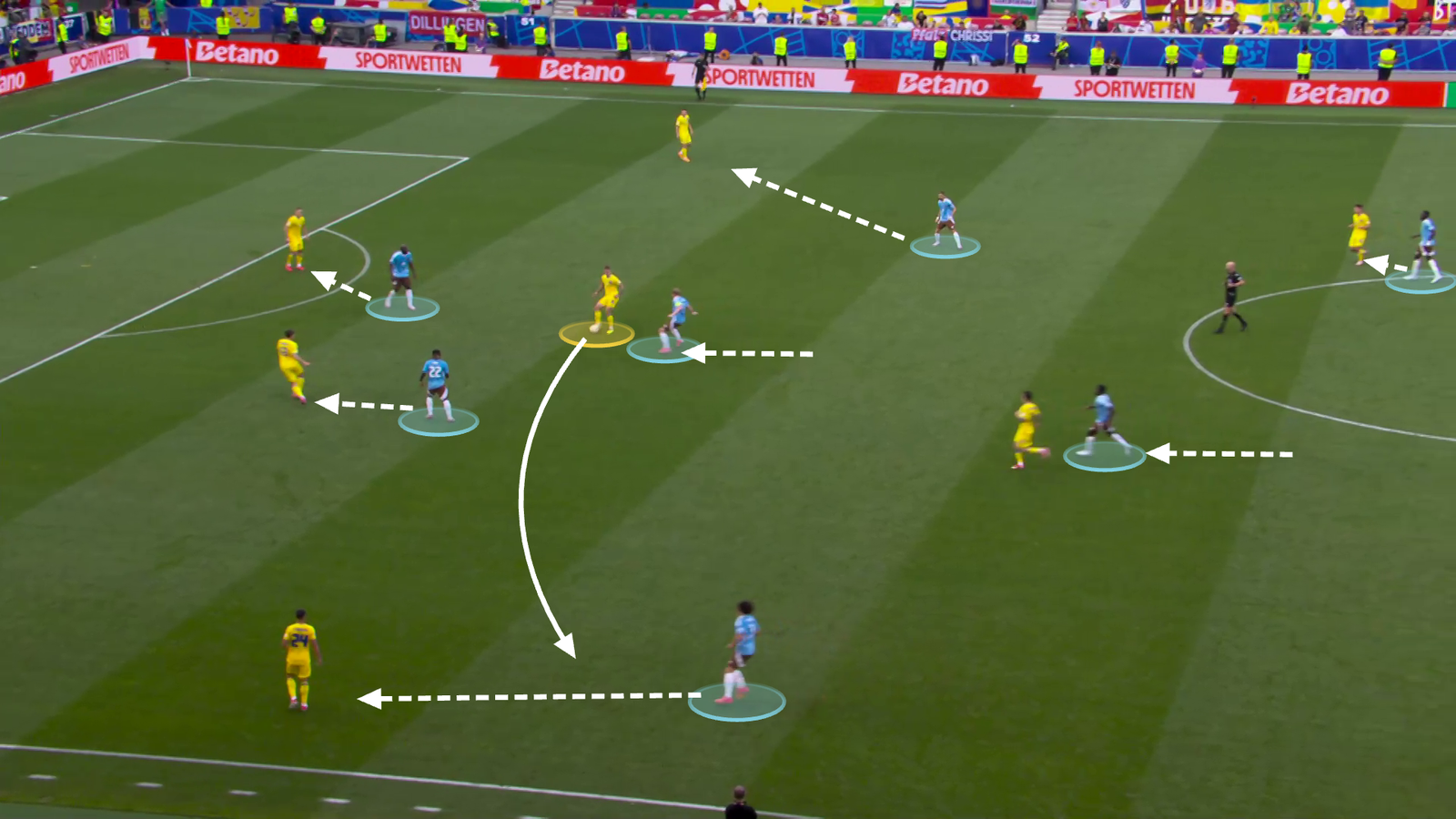

However, of their five final-third regains against Ukraine, four were in the first 25 minutes. Ukraine changed their approach, going into their central midfielders early rather than out wide. This caused Belgium problems because they did not want to overcommit their two defensive midfielders, Onana and Tielemans, who were deeper to protect the centre-backs from Ukraine’s long balls.

Tedesco made a valid point that their (shock) defeat to Slovakia made winning the group particularly difficult (as it allowed other teams to play defensively, knowing that they could qualify without winning again). The reality is that all three games have shown the good, bad and ugly of this Belgium side.

They look a little caught between tactical identities, trying to move on from the Martinez generation but with some residual super-strengths and key players that their iconic 3-4-3 was built around.

If there is one silver lining in Belgium ending up on the side of the draw they have, it is how good a counter-attacking team they can be. This too was a feature of Martinez’s Belgium, most iconically at the 2018 World Cup, and in particular the match-winner against Japan in the round of 16.

Belgium have not been beyond the quarter-finals of a Euros since 1980. That was five years before Tedesco was born. Whether he continues to try to evolve beyond Martinez’s style or leans into Belgium’s tactics from previous tournaments, he is going to have to be near-perfect from here on out.

Read the full article here