Nobody plays 4-4-2 anymore. Correction, nobody attacks with a 4-4-2 anymore.

Almost 44 per cent of Premier League line-ups in the 2008-09 season were a 4-4-2; it is down to just seven per cent this season. Realistically, teams play multiple formations — 43, if you ask Mikel Arteta about his Arsenal side — throughout a game, depending on the phase of play. And the top ones are defending in the midfield third, a mid-block, with a 4-4-2.

“It’s the most malleable formation out of possession,” says Carlon Carpenter, head video analyst at Houston Dynamo of MLS. “It’s the best use of positioning players (based) on space, it covers most areas of the pitch. The clarity makes it really easy to implement, whether you’re a team that likes to high press, you can press out of a 4-4-2, whether you sit deeper and mid-block.”

Defending is principle-orientated and opposition-dependent. Most managers/head coaches want a “plus one” at the back, meaning one more defender than the number of opposition forwards — against a 4-3-3, for example, that’s leaving four on halfway. Man-marking is the norm in midfield, as the best progressors on both teams are usually there, so matching up limits access.

Single pivots — that is, building up with one midfielder deeper and two more playing further forward (picture a point-down triangle) — are standard. By defending in a 4-4-2, one No 9 can cover that pivot, and his partner can press the centre-backs. The front two often switch roles when opponents play across their back line, in a pressing pattern that looks like a pendulum:

Everton manager Sean Dyche calls this a “soft press,” to direct opponents into wide areas and then lock them in out there. His main focus: “How crunched can we make the pitch?”.

Take this example, from Arsenal’s recent 3-1 win against Liverpool. Arsenal press in a 4-4-2 against a 4-3-3, but left-back Joe Gomez rolls inside to create what Jurgen Klopp calls a “double six” alongside Alexis Mac Allister.

No 10 Martin Odegaard harries Virgil van Dijk, to force him wide after Ibrahima Konate passed across the defence. Jorginho is onto Gomez. Benjamin White recognises the next pass and is straight out to Luis Diaz, who Van Dijk passes to.

Carpenter speaks about needing to “really exaggerate the in-to-out defending (pressing wide from a central start point), making sure that you’re really compact. But then, once they actually play that pass wide, because they have nowhere else to go, you press hard. The winger will go hard, a full-back will go hard. That is a one-to-one thing, but the spaces are so limited.”

That can be seen here, with Arsenal four-v-three against Liverpool. William Saliba, the right centre-back, has tucked round to cover White. Diaz does not even manage to face up the full-back, and returns the ball to his goalkeeper.

Here’s an example of the plus-one at the back allowing a centre-back to follow a No 9. Gabriel Magalhaes steps with Diogo Jota, forcing him to bounce Alexis Mac Allister’s midfield-splitting pass straight back where it came from.

Then, when Liverpool go back out to the left, Arsenal make the same pendulum press, but tweaked slightly with Jorginho stepping to Gomez (rather than Havertz, who can stay on Mac Allister). Odegaard locks in Van Dijk and Liverpool have to play backwards.

Out of options to play through or round, Liverpool are forced into going over. Goalkeeper Alisson comes all the way into the midfield third and kicks long — Saliba heads it clear. Over 75 seconds of settled Liverpool possession and no meaningful touches in the final third.

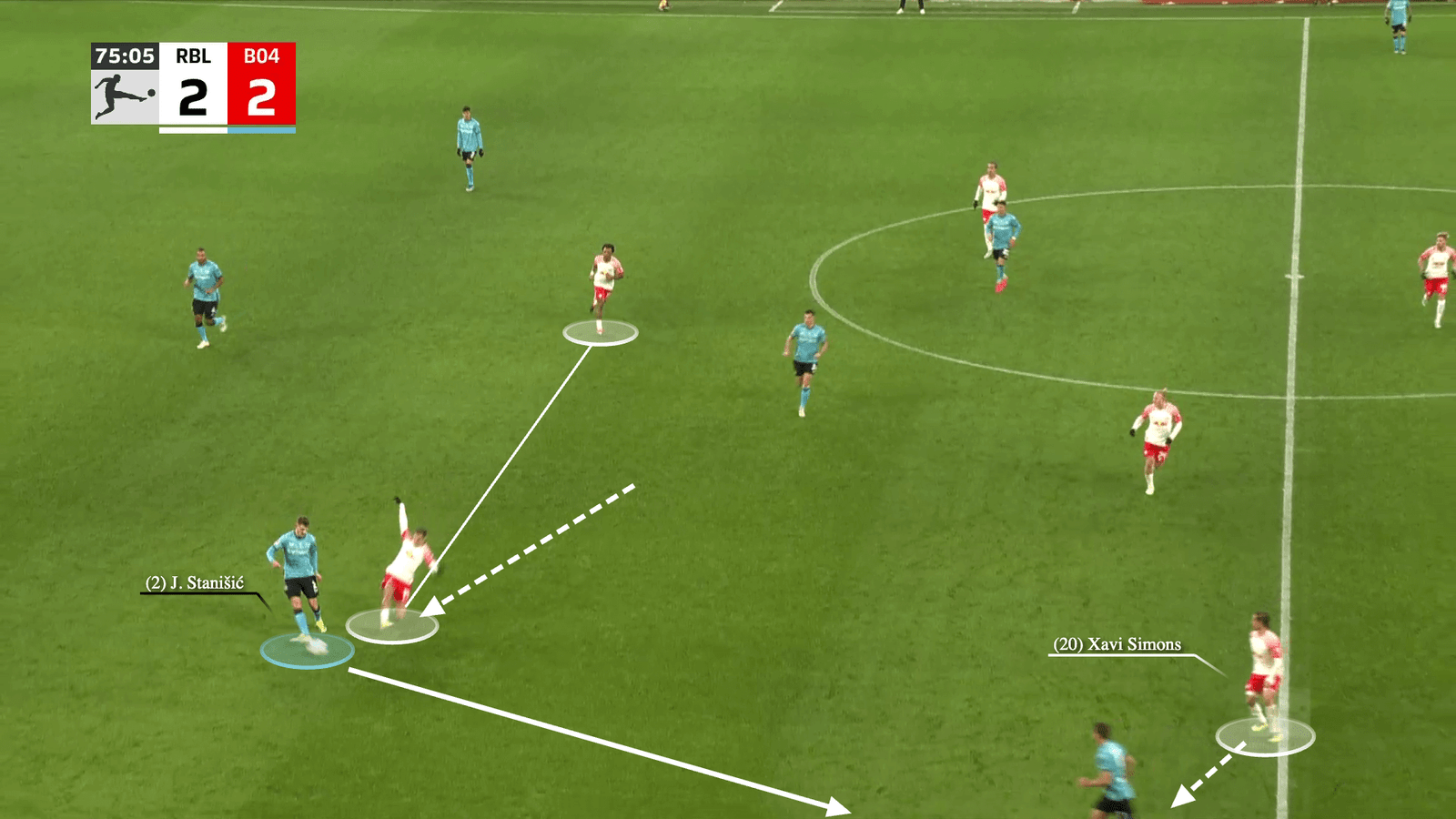

Here is an example from RB Leipzig’s recent 3-2 loss against Bayer Leverkusen.

Leipzig have to wait to press, with Leverkusen’s back three and wing-back shape able to escape out wide if a No 9 presses too early. Leipzig sit off for almost 20 seconds.

Front two Yussuf Poulsen and Lois Openda drop onto Leverkusen’s double pivot — Dyche calls this “north side” screening, and against better teams they might go “south side”, for added protection. The wingers tuck in to prevent direct access to Leverkusen’s No 10s.

Then, as middle centre-back Jonathan Tah passes wide, Leipzig come alive. Poulsen darts wide to press Josip Stanisic, backed up by left-winger Xavi Simons.

Leverkusen are forced back to goalkeeper Lukas Hradecky, then Leipzig press again and force a regain.

The increase in mid-block defending is a result of more teams building up short, a trend rooted in former central midfielders becoming managers and head coaches.

The average Premier League possession this season lasts 25.2 seconds, more than four seconds longer than in 2018-19 — Opta define possessions as one or more sequences in a row by the same team, ended by the opposition gaining control of the ball. There are over 28 sequences of 10-plus passes per game (by both teams combined), a 15 per cent rise from five years ago.

More settled possession means teams have to find solutions to prevent being played through, stop opponents accessing their best players and set traps to press them into errors and wide spaces.

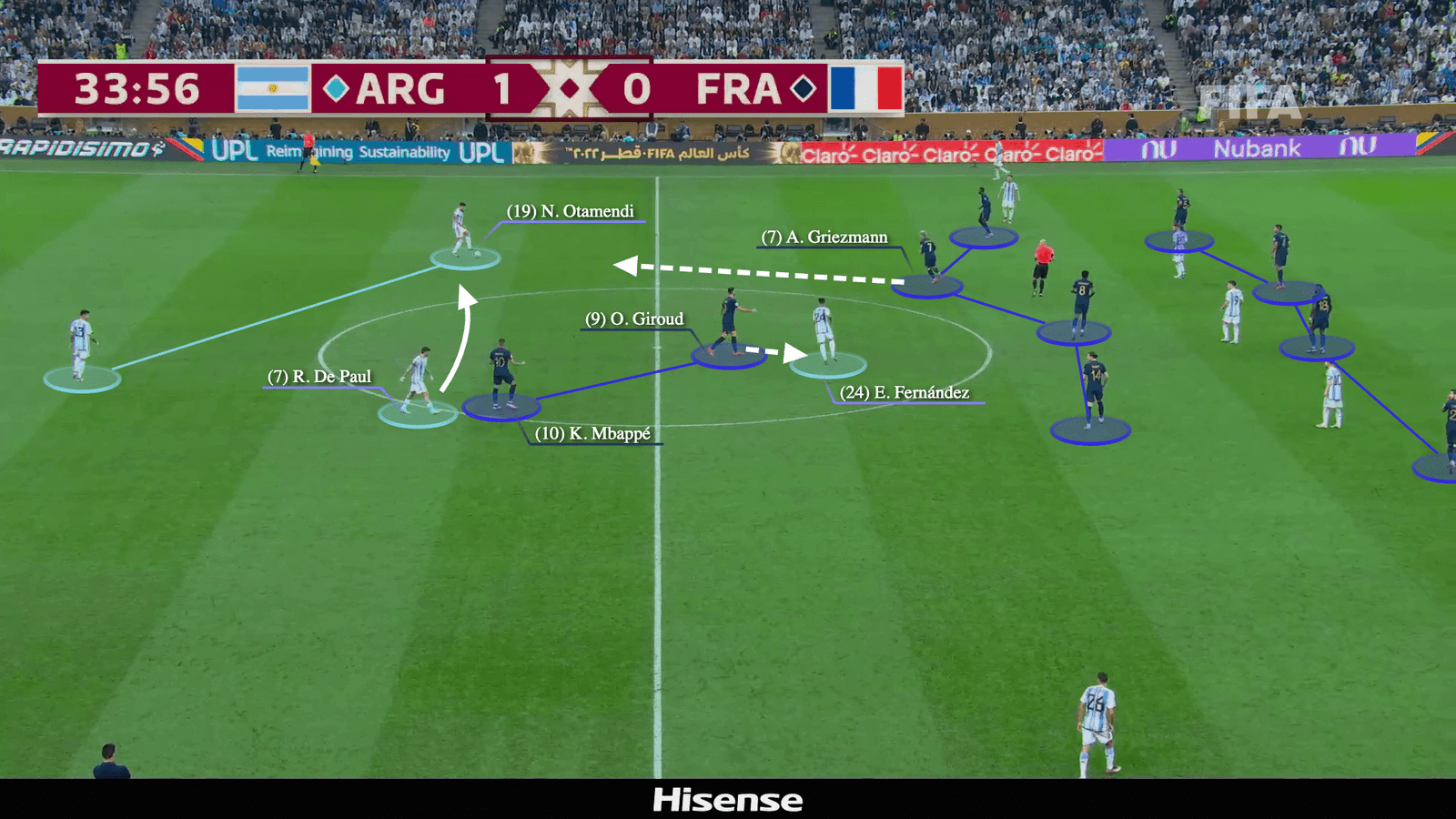

Defensive principles are part of a club’s game model, which Carpenter describes as “a skeleton you base everything off — from recruitment to tactical style”. World Cup 2022 winners Argentina, its runners-up France and beaten semi-finalists Morocco were three of the tournament’s top four teams for the share of defending time spent in a mid-block. Argentina and France both defended in a 4-4-2.

Didier Deschamps gave a reduced defensive role to Kylian Mbappe, with opposite number Lionel Scaloni doing the same for Lionel Messi. They played next to the No 9, with central midfielders stepping out to press the opposition back line.

Here is an example of Antoine Griezmann doing so for France in the final.

International and domestic football will always contain tactical disparity.

In an increasingly physical sport having straightforward principles, which manifest into clear responsibilities, is essential.

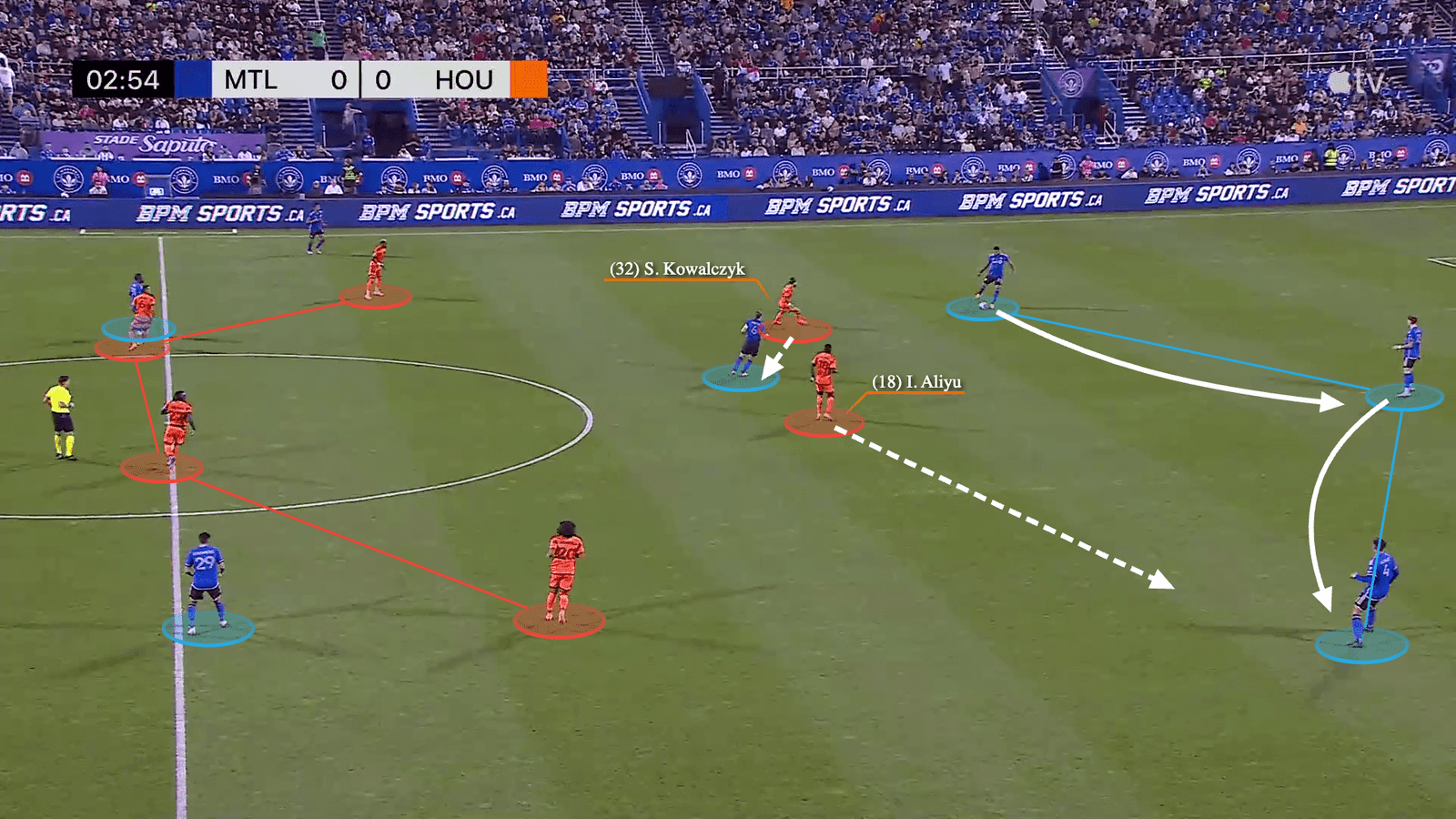

“A major part of it has to be that we (Houston) played 50-something games last year,” says Carpenter. “We probably had an average of two a week. The actual time that you’re getting to work with players to add these really complex (pressing) tweaks is limited.”

Houston tried a 4-3-3 press in the 2023 pre-season but switched to a 4-4-2 as it better suited the physical profiles of their forwards and midfielders. They reached the title play-offs while conceding just 27 through balls in their 34 league games, the second-fewest of any side.

Here is an example of them pendulum pressing, away against Montreal in October, building up with a back three.

Top sides recruit players with outstanding physical and technical profiles.

Quick wingers are as effective at pressing a full-back as they are attacking them one-v-one. Tall, athletic centre-backs — Arsenal’s William Saliba being the prime example — are immune to the traditional issue of defending wide spaces, and can comfortably track an opposition No 9 if they drop in against a high press.

Pep Guardiola spoke last season about needing “a proper defender to win duels one-v-one. In the Champions League, at that level, they (only) need one action to beat you”. His Manchester City side’s mid-block in a 4-4-2 and their compactness was fundamental in them finally winning the Champions League.

Guardiola demonstrated the flexibility offered by the 4-4-2.

City would shift into a 4-2-4, pushing their wingers up to press opposition centre-backs. It underpinned their 7-0 thrashing of Leipzig, who attacked in that round of 16 second leg with a narrow 4-4-2. City pressed with the same structure in the final three months later, against Inter Milan’s 3-5-2.

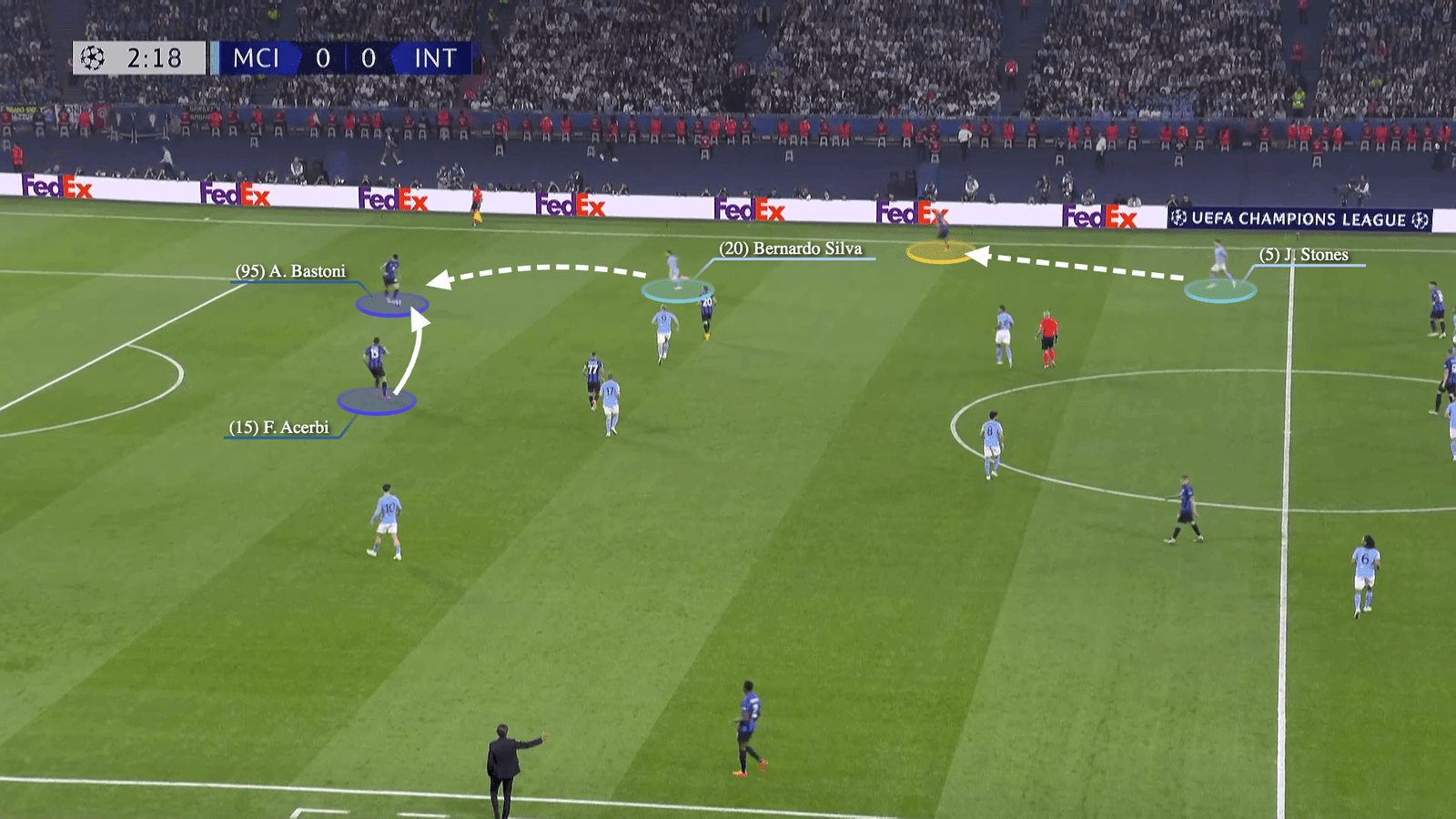

Here is an example of out-to-in winger pressing from that latter game, where Bernardo Silva arcs his run to prevent Alessandro Bastoni passing to left wing-back Federico Dimarco — right-back John Stones steps forward in case Bastoni tries to reach Dimarco anyway.

With the left side blocked, Inter play across to the opposite flank. Right centre-back Matteo Darmian is then pressed the same way by left-winger Jack Grealish and has to pass centrally to No 8 Nicolo Barella.

This initially looks problematic for City, as teams defend in a 4-4-2 to deny central progression, but when their midfield lock on, Barella is forced wide to Denzel Dumfries. Nathan Ake steps out to the wing-back and locks him in.

Dumfries has no other choice but to try to pick out the front two, but underhits his pass and Rodri makes a regain.

In 2012, Arsene Wenger, then the Arsenal manager, said the 4-4-2 was “best suited to the dimension of the pitch.” He was speaking from an attacking perspective, but it shows the cyclical nature of football that, just over a decade later, the same formation is best suited to defending positional attacking sides.

Dyche, Guardiola, Arteta, Deschamps and Scaloni are rarely seen as tactically united, but all of them are 4-4-2 coaches — defensively, anyway.

Read the full article here