How will Italy set up under Luciano Spalletti? What’s the Spanish quirk we should look out for? What can we expect from Albania?

Euro 2024 is nearly upon us and The Athletic will be running in-depth tactical group guides so you know what to expect from every nation competing in Germany.

We’ll look at each team’s playing style, strengths, weaknesses and key players, and highlight things to keep an eye on during the tournament.

Expect to see screengrabs analysing tactical moments in games, embedded videos of key clips to watch, the occasional podcast clip and data visualisation to highlight patterns and trends — think of yourself as a national team head coach and this a mini opposition dossier for you to read pre-match.

This time we’re looking at Group B, which features Spain, Italy, Croatia and Albania.

Spain

- Manager: Luis de la Fuente

- Captain: Alvaro Morata

- Qualifying record: P8, W7, D0, L1, GF25, GA5

- Euro 2020: Semi-finals

- Most caps in squad: Alvaro Morata (73)

- Top scorer in squad: Alvaro Morata (35)

How do they play?

If you haven’t watched Spain for a while and have only a basic idea about how they might play, you are still probably on the right track.

Under head coach Luis de la Fuente, Spain are still looking to dominate possession in a 4-3-3 shape on the ball with a focus on combinations down the flanks between the winger, the full-back and the No 8.

The prominence of Spain’s wingers, such as Lamine Yamal, has also led to more crosses into the penalty area. In Euro 2024 qualifying matches, De la Fuente’s side had the fourth-most crosses per game (26.3) of the 53 nations competing for a place in the final tournament.

This approach tallies well with the head coach’s choices for the striker position. Morata is strong in the air and Joselu has been making a positive impact off the bench, too, scoring four goals from his nine substitute appearances.

On top of that, Mikel Merino, Fabian Ruiz or whoever is playing as a No 8 constantly makes off-ball runs into the box to provide the winger or the full-back with multiple options.

Another feature of Spain’s game in possession is Morata’s tendency to drop and offer himself as a passing option in the middle of the pitch, which makes him a viable option as a false nine if he is needed to play that role.

Off the ball, Spain defend in a 4-4-2 — like the majority of the top football teams in the world — with one of the central midfielders moving up next to Morata or Joselu. When they lose possession, they focus on winning the ball back quickly to limit the opponent’s transitions.

Their key player(s)

The level Rodri has maintained in the last couple of years positions him as one of the best midfielders in the world, if not the best. He is vital to Manchester City and Spain.

Rodri’s ability to dictate the tempo, receive the ball under pressure and split the opponent’s line is only matched by his off-ball prowess. He is always in the right position when his team have the ball, which allows him to win the ball back quickly once it is lost, and his defensive presence is complemented by his smart positioning when Spain are out of possession, too.

Great players might drop a level or two on the international stage, but Rodri elevates Spain to another dimension.

(Denis Doyle/Getty Images)

Pedri has only featured twice for Spain since the 2022 World Cup, and the recurring muscle injuries meant that he only started 21 matches for Barcelona in the 2023-24 season.

His match fitness is a concern, but he is Spain’s best No 8 and his performance against Northern Ireland on Saturday should bring back some hope regarding the levels he could reach in the tournament.

What is their weakness?

Not necessarily a weakness in their playing style, but missing Gavi, one of their best midfielders, is Spain’s biggest problem entering this tournament. Gavi was the only player to feature in all of De la Fuente’s games until his injury against Georgia. His off-ball movement and intensity were crucial in Spain’s qualifiers and those qualities will be missed.

One thing to watch out for…

If Spain’s passing combinations down one side of the pitch are halted by the opponent’s defence, they look to switch the ball quickly to the other side to try to put their winger in a one-versus-one situation or create an overload using the full-back.

Looking at the number of attempted switches of play — which is defined by Opta as any pass that travels at least 60 per cent of the width of the pitch — Spain’s 7.5 per game was the second-most of all teams competing in the Euro qualifiers after Georgia (8.1). In terms of successful switches of play, their 6.5 per game topped the charts.

These switches of play are often played by Rodri, who is instrumental to a similar attacking move at City.

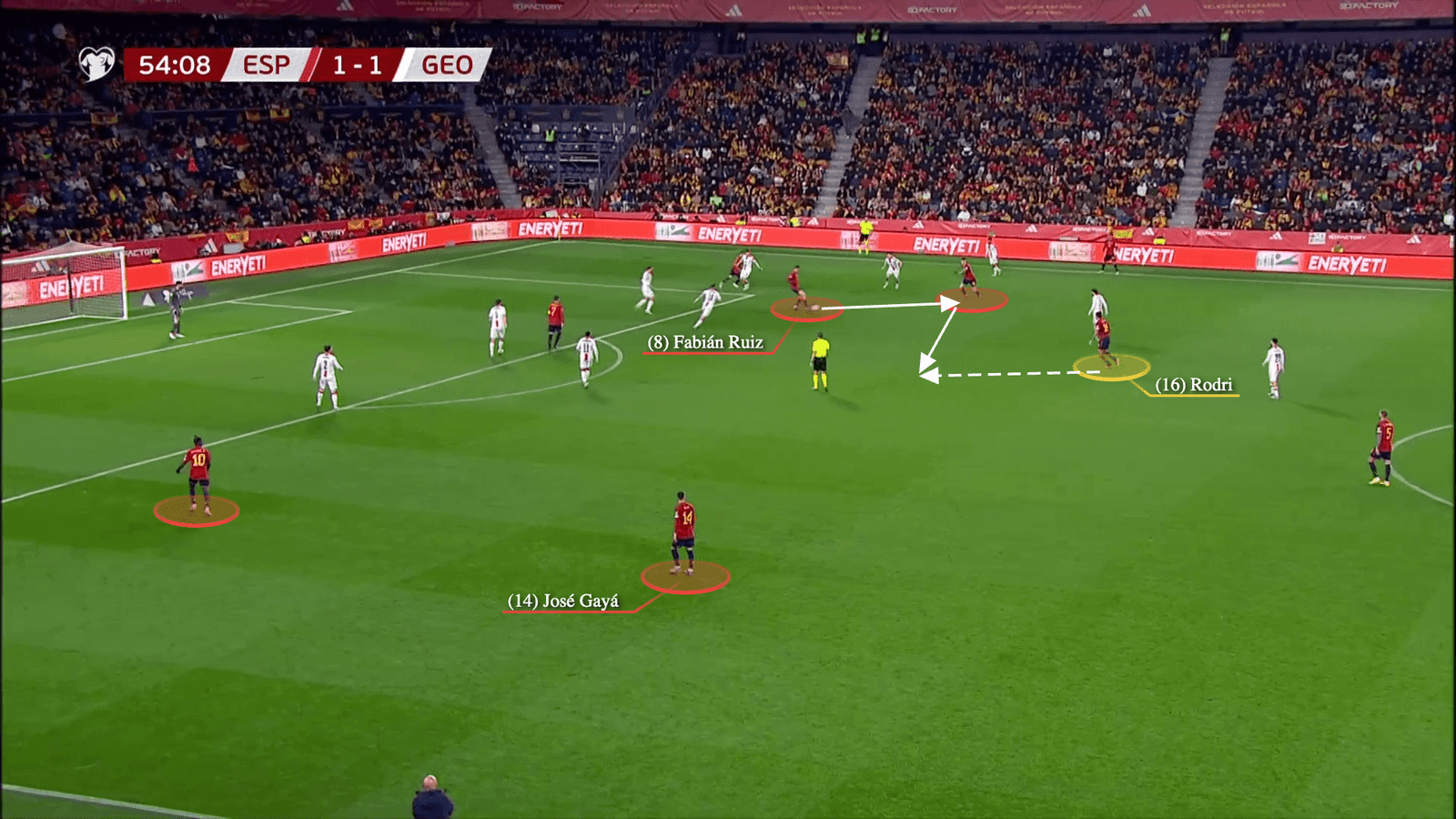

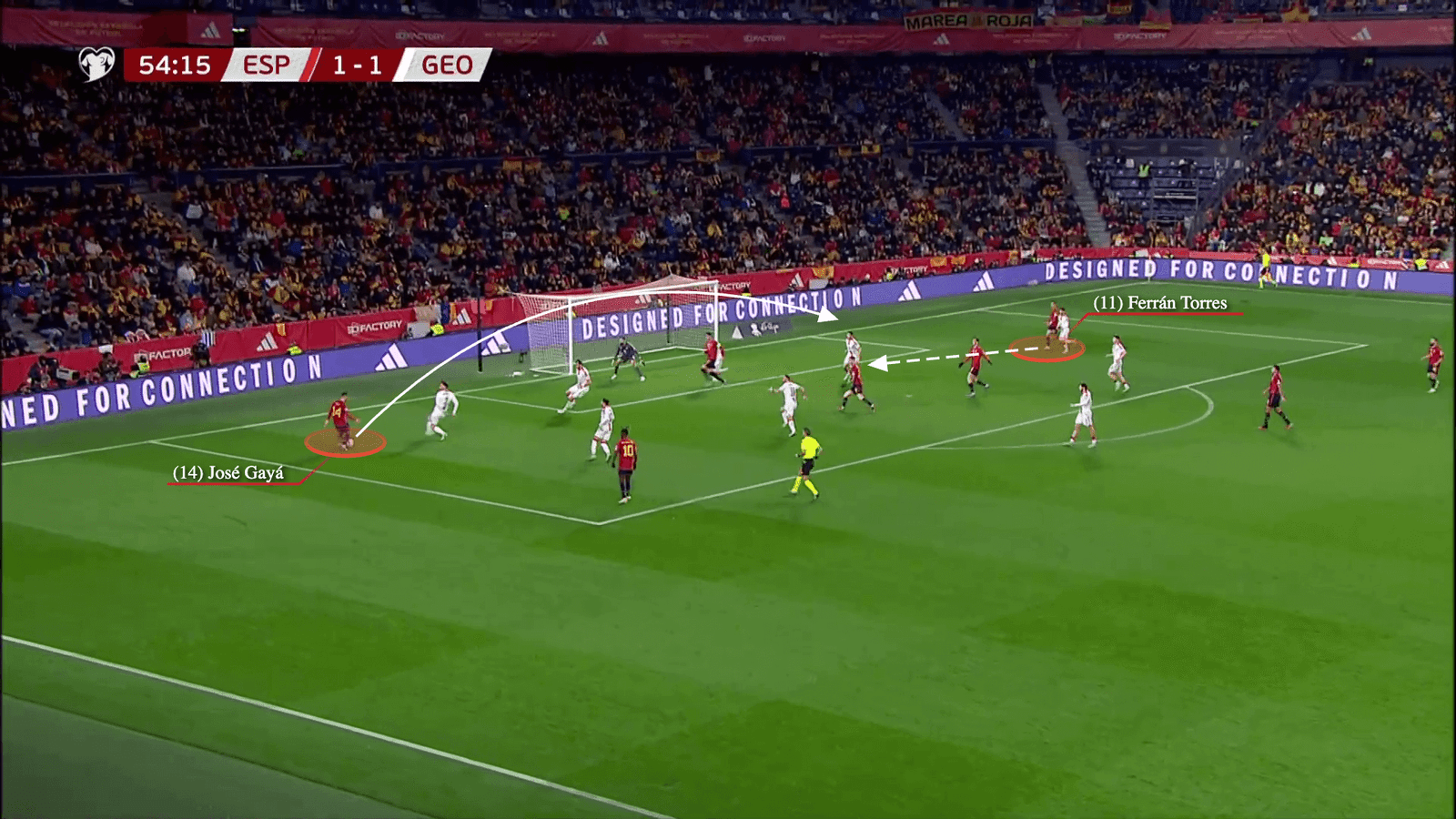

One example is Ferran Torres’ goal in the 3-1 victory against Georgia last November. Here, Fabian Ruiz roams towards the right wing and combines with Oihan Sancet to find Rodri…

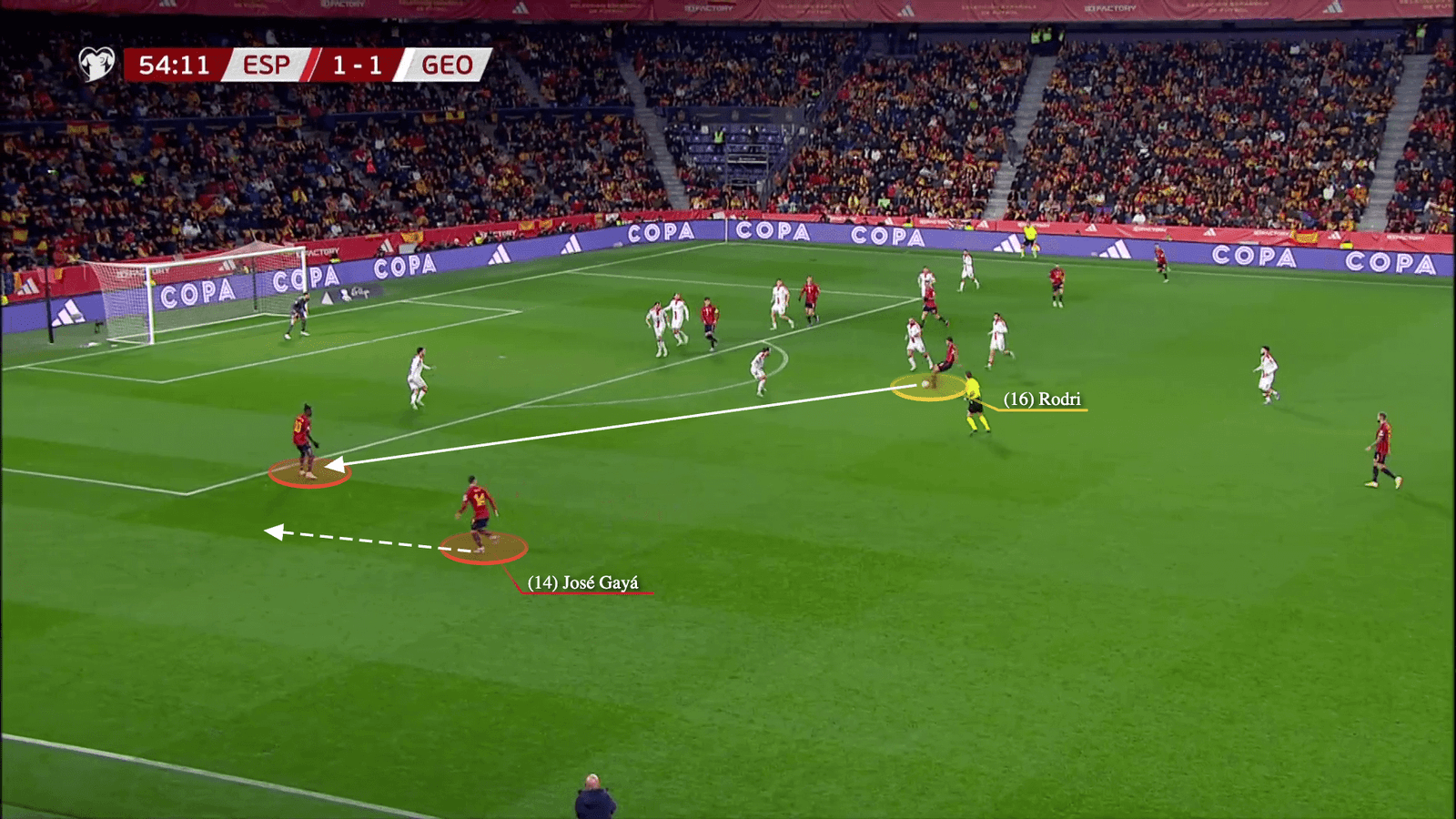

… who switches the play to Nico Williams and Jose Gaya before Georgia’s defensive block can shift across…

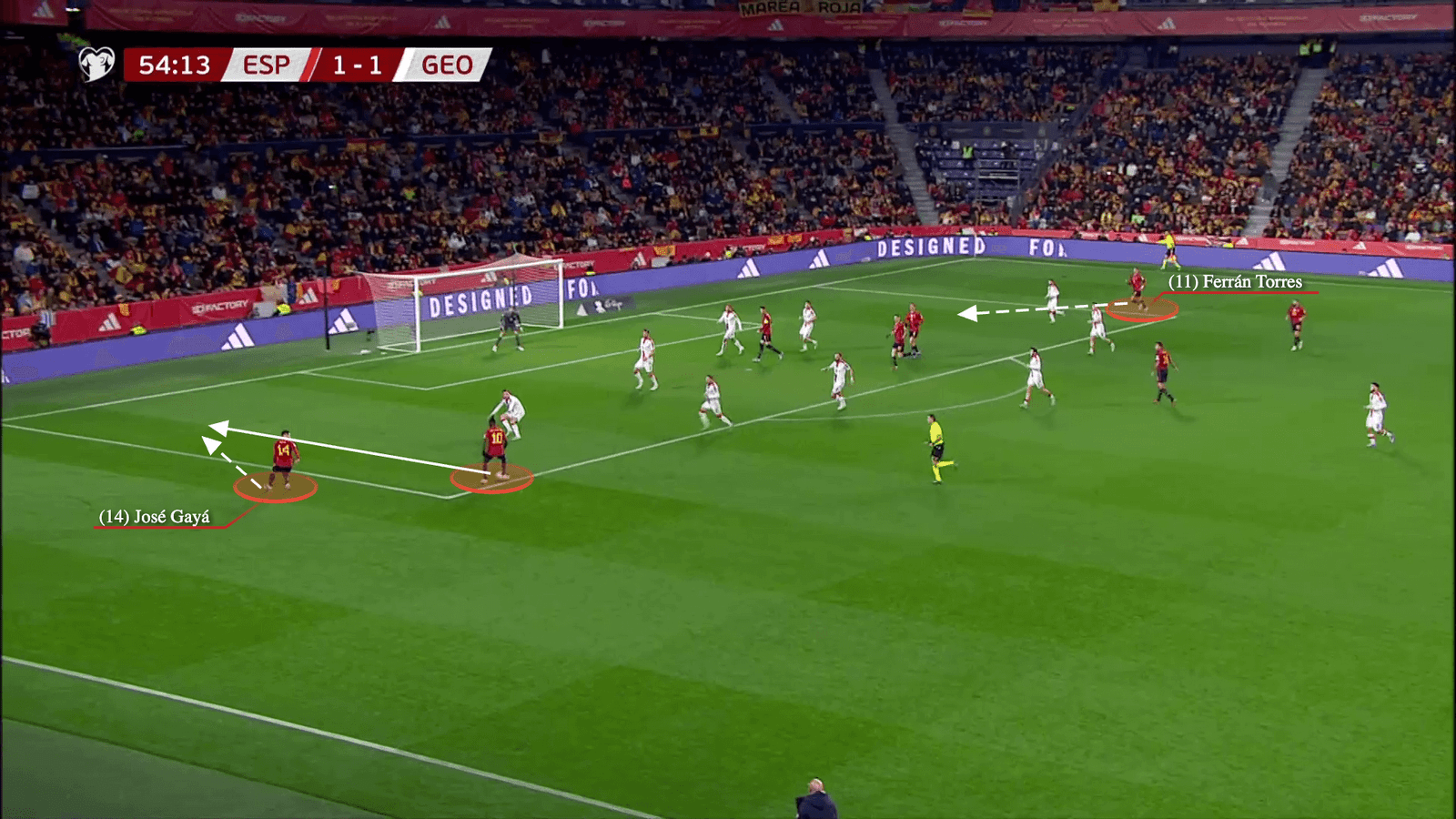

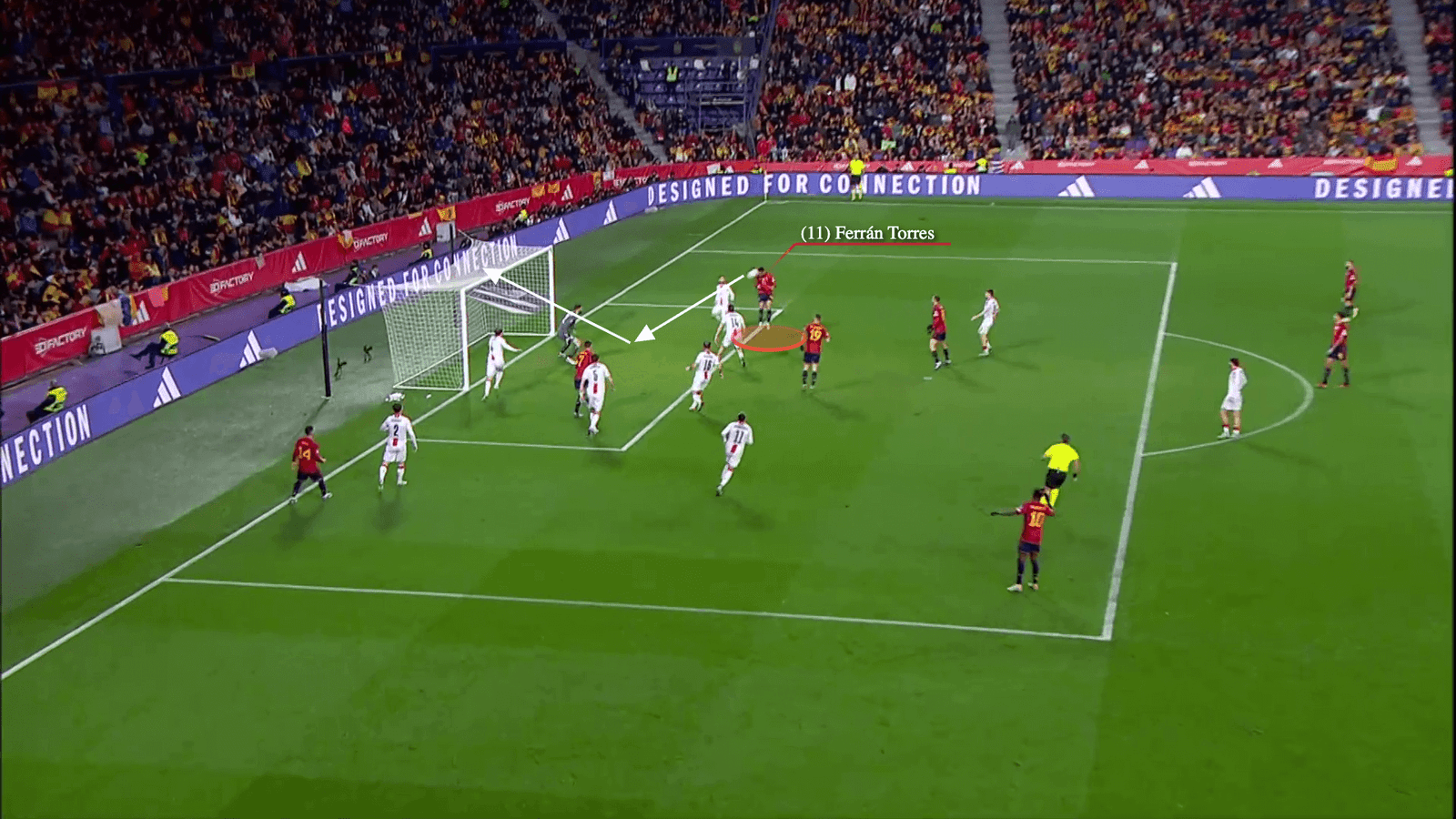

… leaving their right wing-back, Otar Kakabadze, in a one-versus-two situation. Williams finds Gaya’s overlap, while on the other side, Torres starts his run to attack the back post…

… and Spain’s left-back plays the ball towards that area, for Torres to head the ball into the net.

Italy

- Manager: Luciano Spalletti

- Captain: Gianluigi Donnarumma

- Qualifying record: P8, W4, D2, L2, GF16, GA9

- Euro 2020: Winners

- Most caps in squad: Gianluigi Donnarumma (62)

- Top scorer in squad: Nicolo Barella (Nine)

How do they play?

Until last March, Luciano Spalletti looked set on playing with a back four. However, the Italy manager said that he wanted to do “something modern” before the friendlies against Venezuela and Ecuador in March.

“There is an openness now to being footballers who know how to interpret multiple systems within the same match,” said Spalletti. “Before we had little time and we only focused on one system. Even when we lost, I said we would stay in that system, but now there is more time to do something different.”

The difference was moving to a back three instead of the back four Italy implemented in Spalletti’s games in the Euro qualifiers. In his first six games, Italy’s 4-3-3 in possession depended on wing play with flexible rotations between the full-back, No 8 and the winger to break down teams in the wide areas.

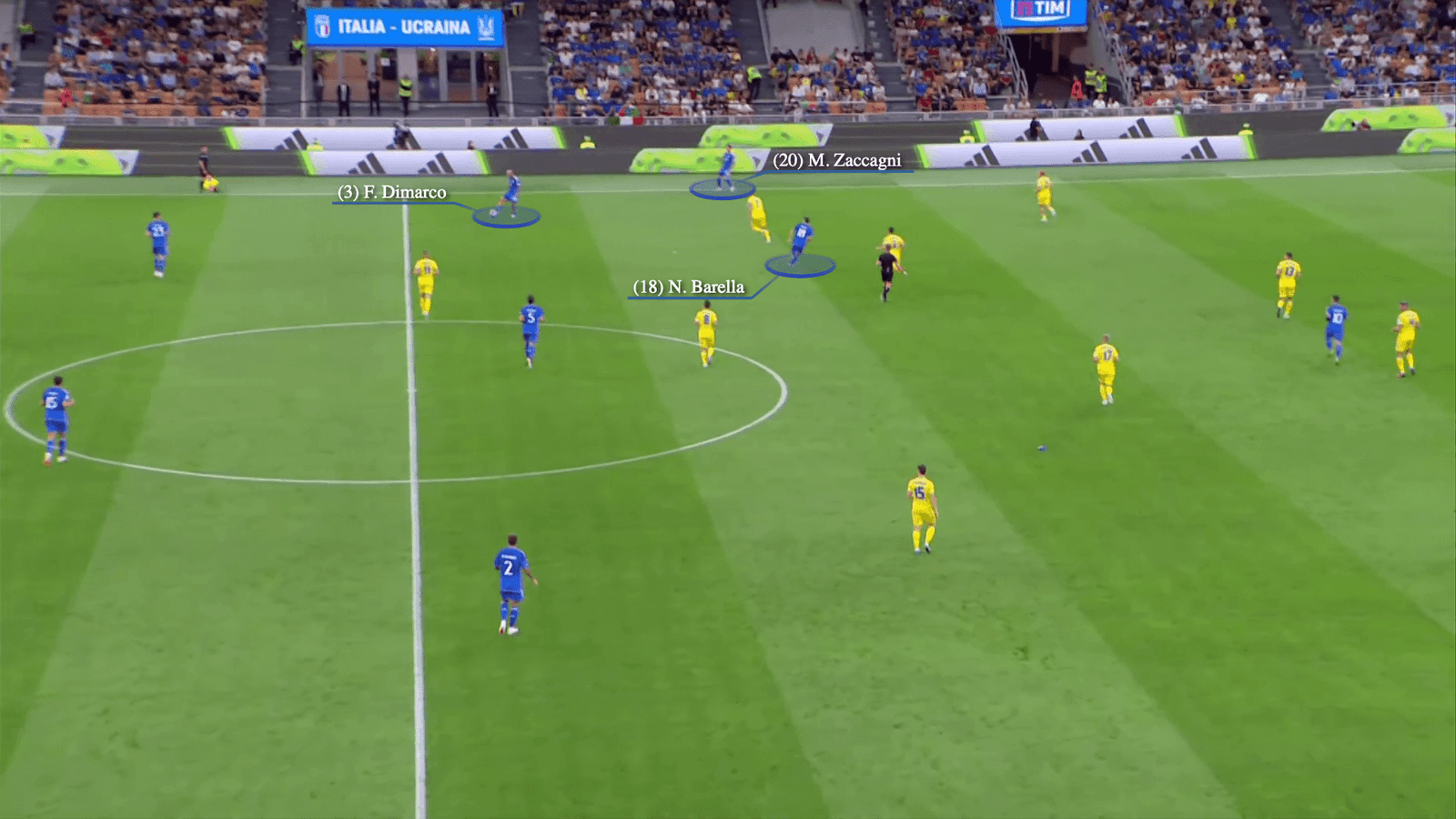

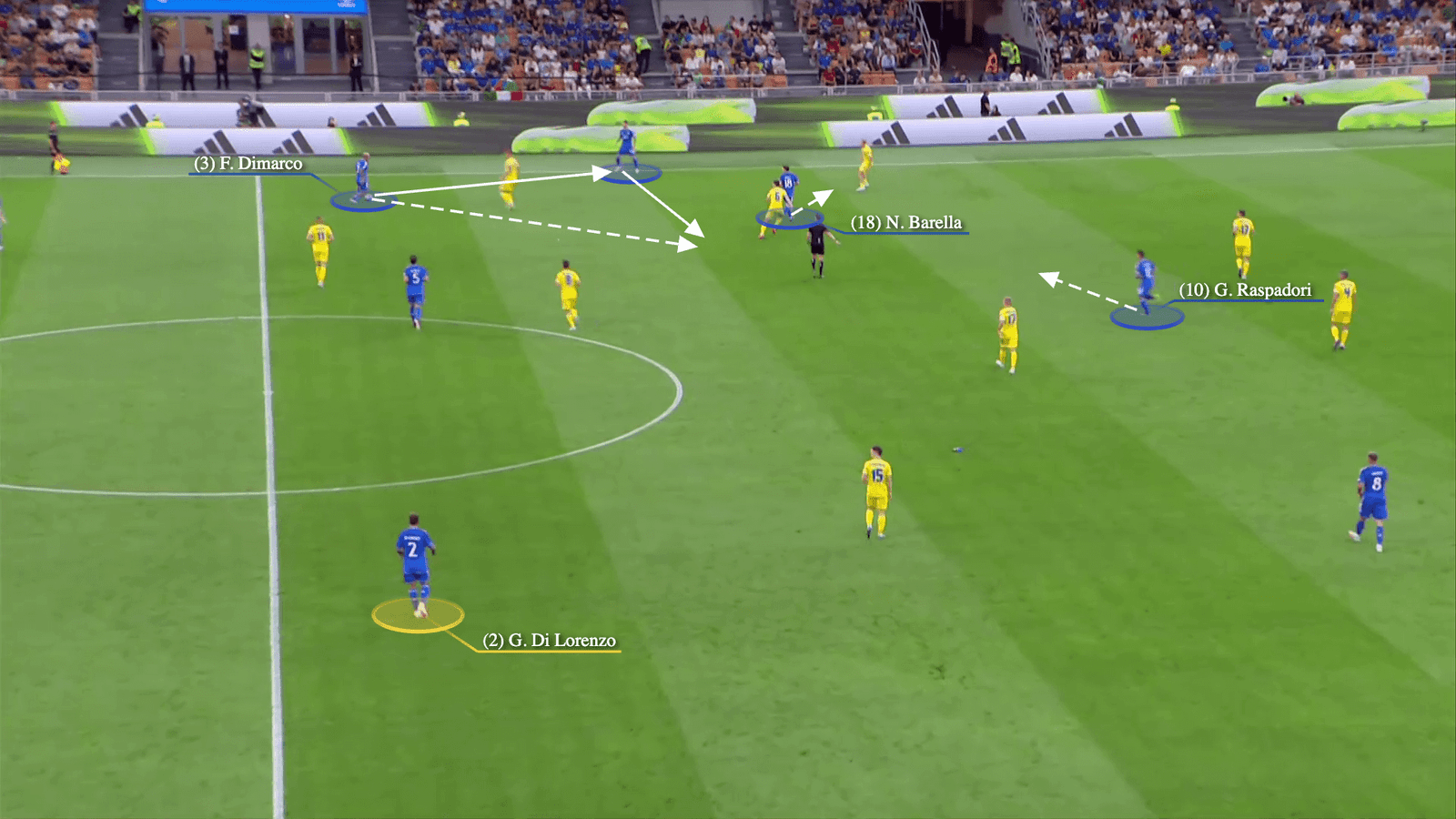

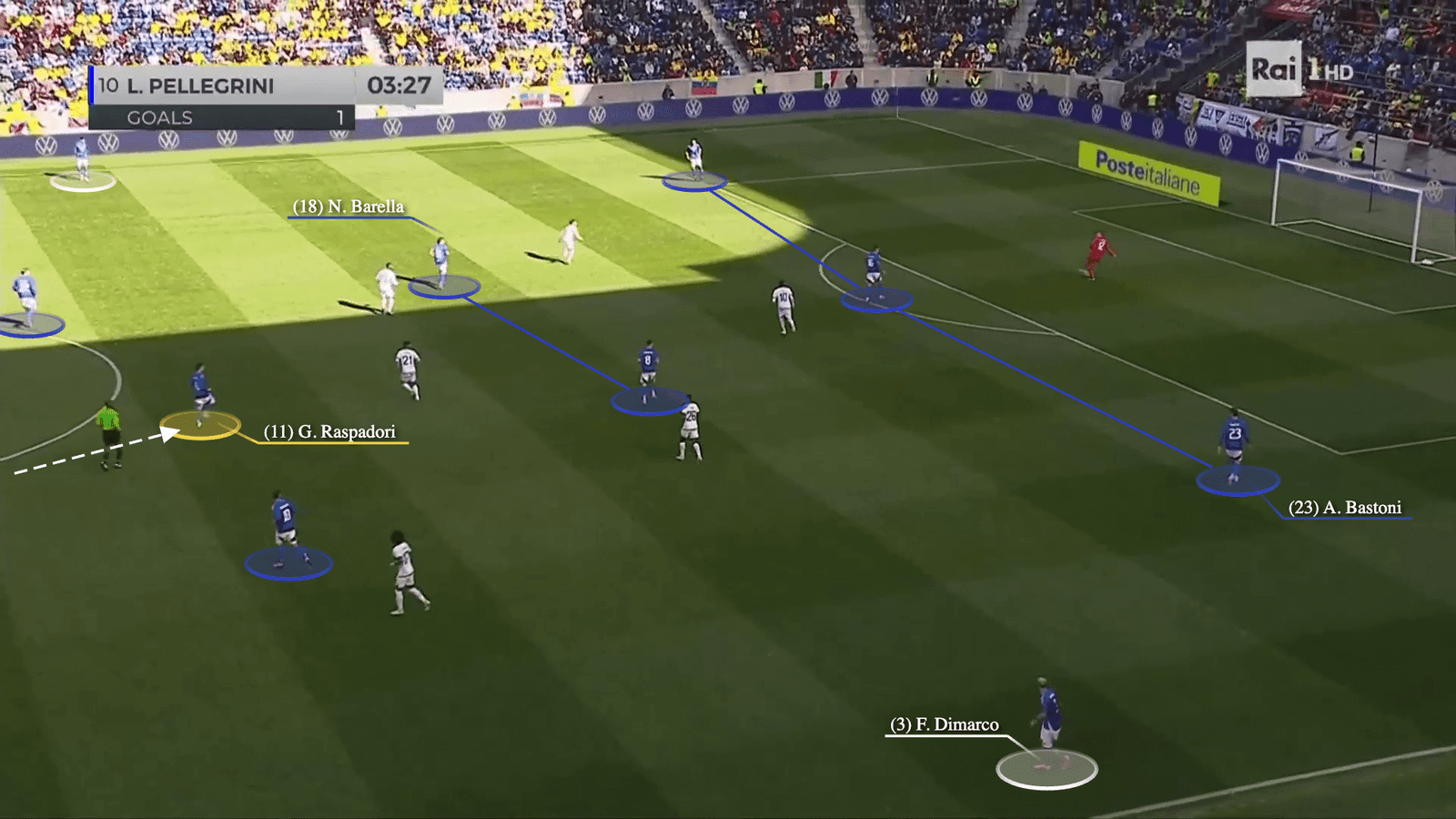

In this example, against Ukraine last September, Barella’s movement drags Taras Stepanenko and creates space in midfield, which is attacked by Italy’s full-back, Federico Dimarco, after combining with Mattia Zaccagni. Complementing that movement was Giacomo Raspadori dropping from a centre-forward position to provide a passing option, but the interesting role in Italy’s wide combinations is the opposite full-back — Giovanni Di Lorenzo in this sequence.

After Dimarco plays the ball to Raspadori, and the Napoli forward combines with Davide Frattesi (Italy’s No 8 above), he finds Di Lorenzo unmarked in a narrow position after Ukraine’s left-winger Viktor Tsygankov has dropped to protect his left-back.

The time Di Lorenzo has on the ball allows him to pick his pass, but despite the move not ending in a goal, it’s an attacking sequence that Spalletti’s team has been using regularly when Italy have played in a 4-3-3.

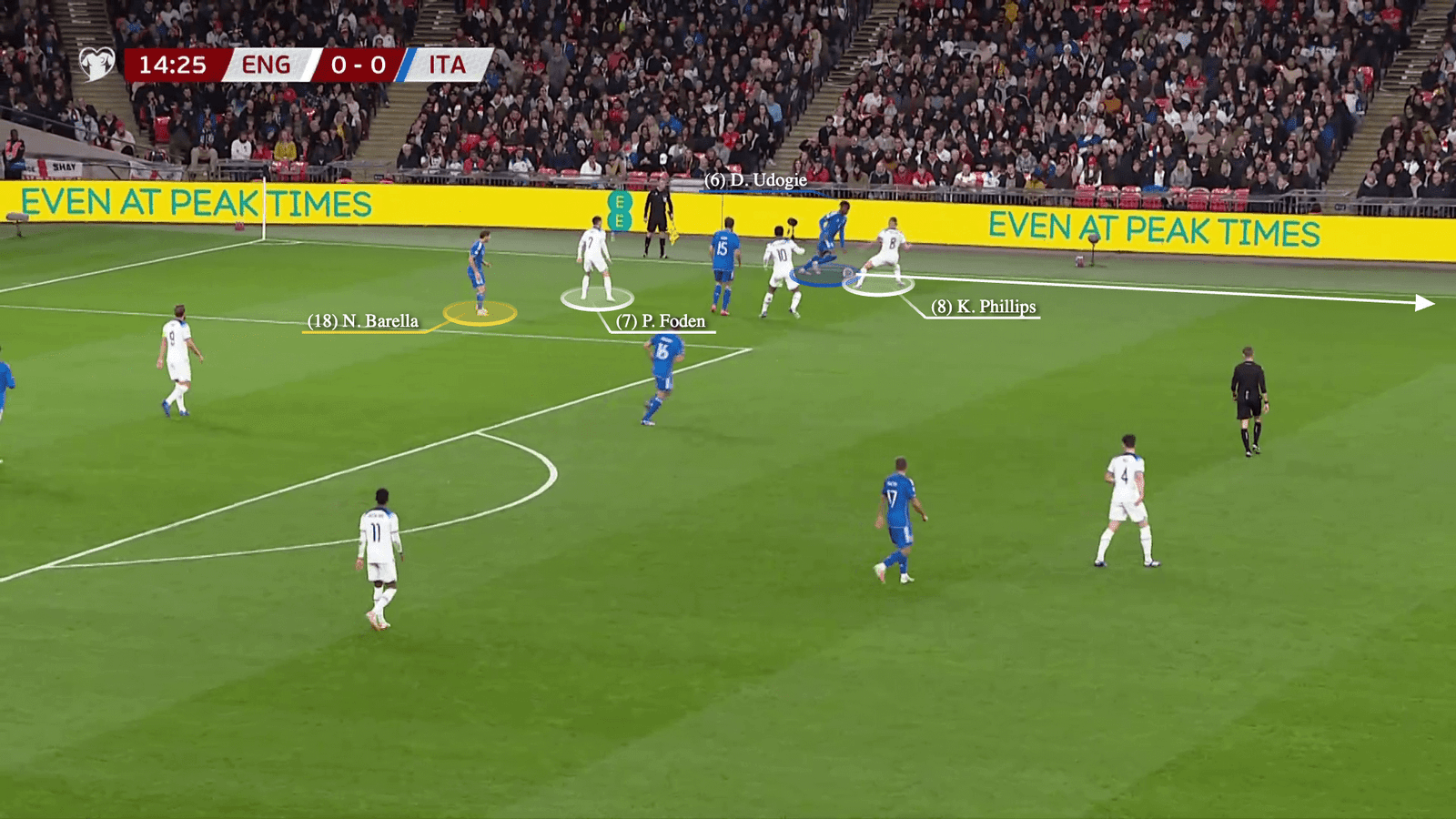

That move resulted in their only goal against England the following month. Here, Barella’s rotation to the left-back space forces Kalvin Phillips to press Destiny Udogie as Phil Foden focuses on the Inter Milan midfielder. Italy’s left-back then combines with Stephan El Shaarawy to exploit the space in England’s midfield, before carrying the ball forward…

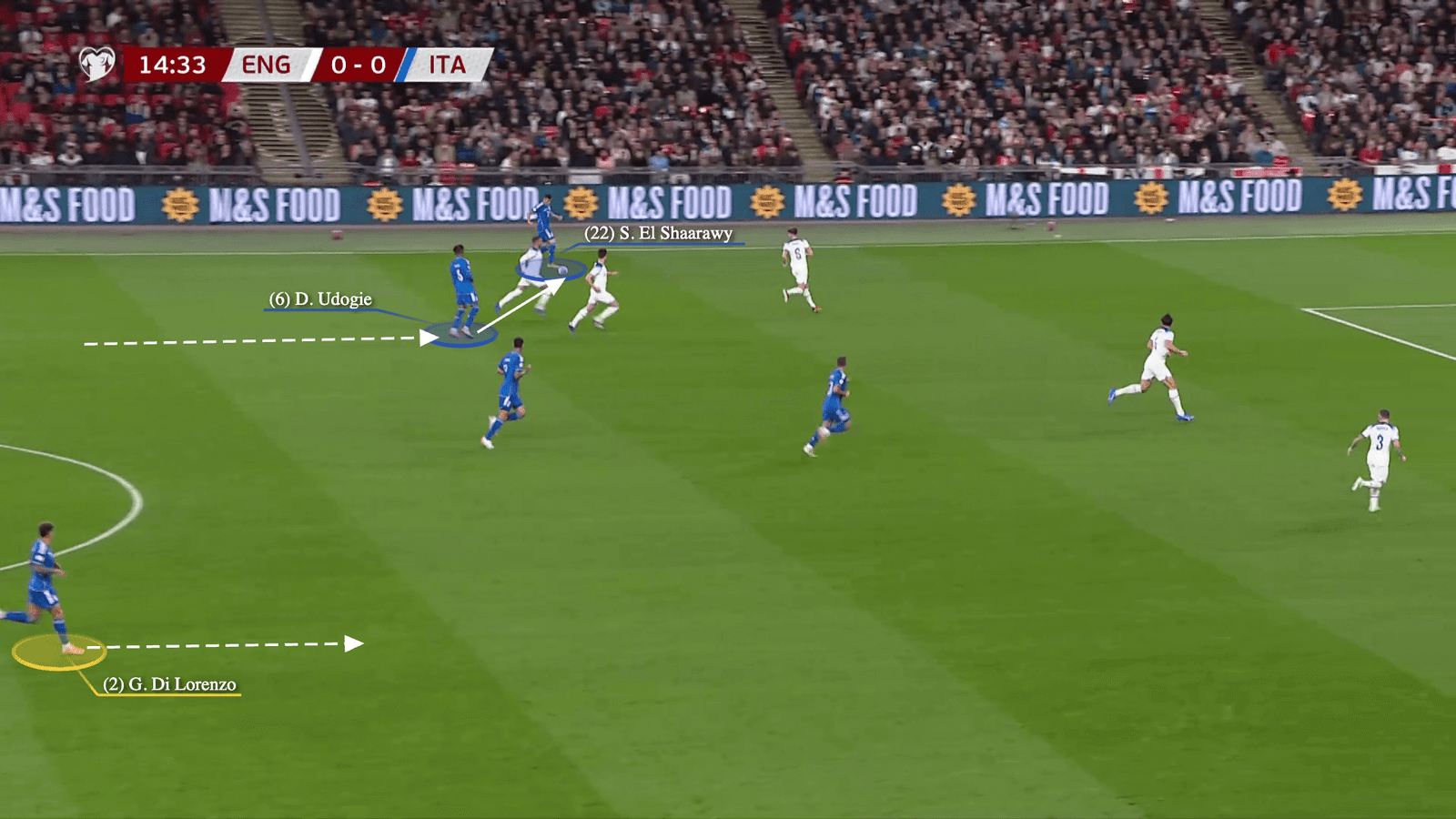

… and playing it wide to the left-winger. Meanwhile, Italy’s right-back, Di Lorenzo, advances on the other side…

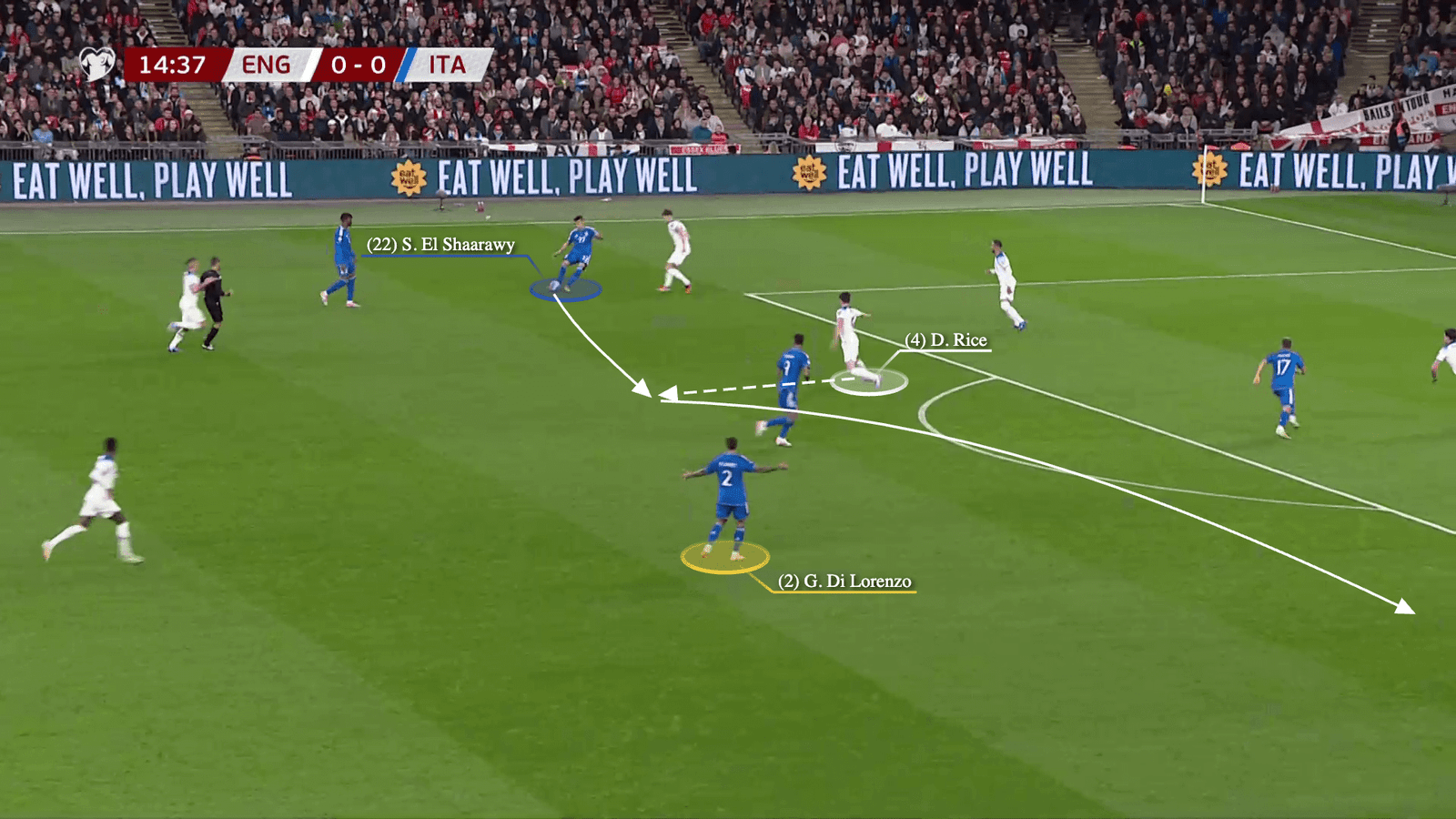

… and is in a position to receive the switch of play, with Marcus Rashford late to the action. El Shaarawy spots Di Lorenzo, but his pass is intercepted by Declan Rice and the ball falls to Domenico Berardi (out of shot) on the right wing.

Di Lorenzo’s narrow positioning allows him to make an underlapping run behind Kieran Trippier, which is found by Berardi, before the right-back’s low cross into the penalty box is attacked by Gianluca Scamacca to give Italy the lead.

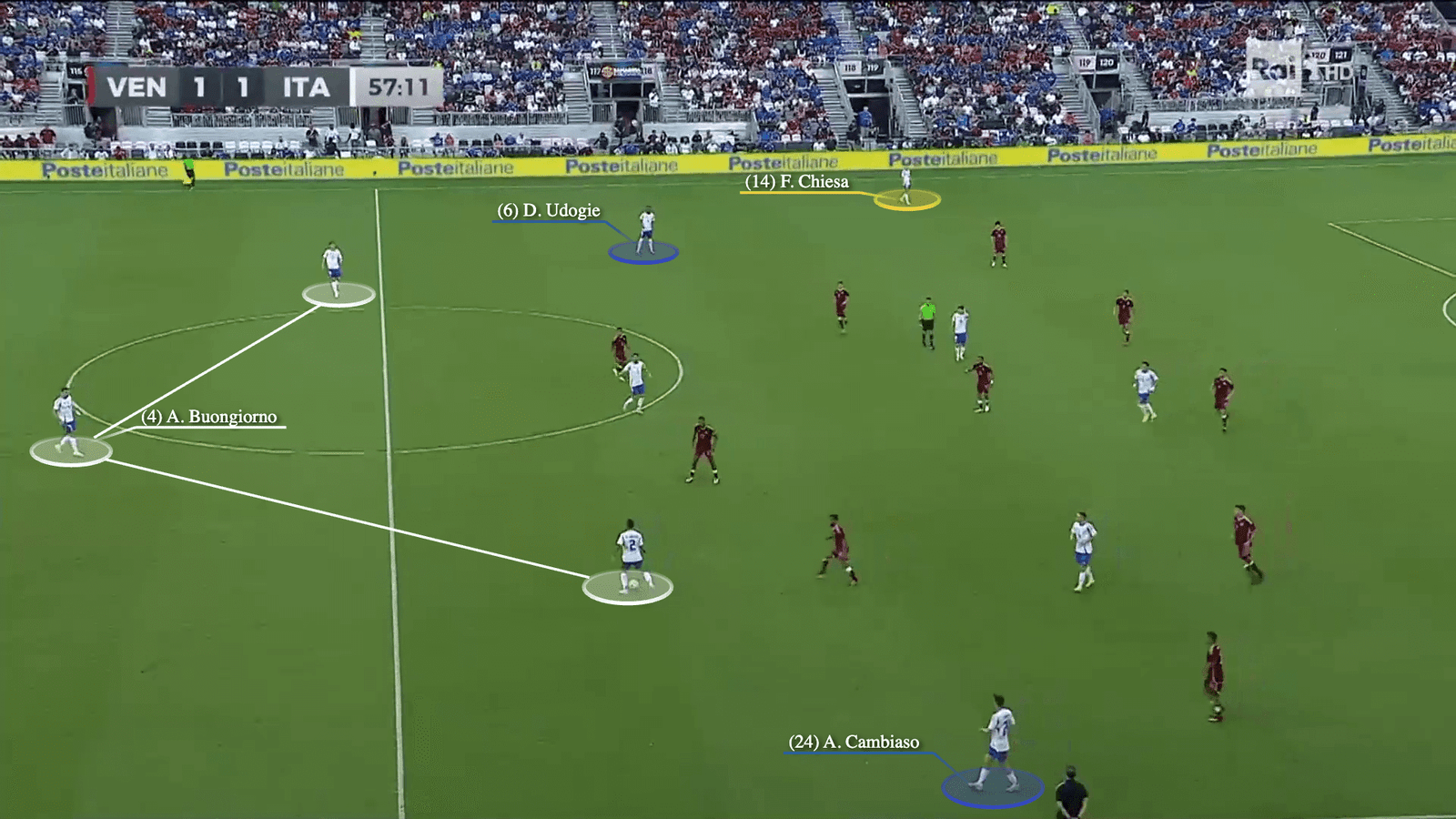

As for the back-three scenario, Italy have used different formations in possession while maintaining a solid 5-4-1 shape without the ball. Against Venezuela, Federico Chiesa’s participation meant that Spalletti’s 3-5-2 on the ball was lopsided because the Juventus forward excels in space and one-versus-one situations down the wing rather than central areas.

The 3-2-4-1 shape used against Ecuador was more fluid, and Raspadori’s link-up play helped Italy’s passing combinations in central areas.

Despite attacking in a different shape, Spalletti’s side focused on combinations between the No 10, wing-back and No 6, allowing the wide centre-backs to exchange positions with the wing-backs.

The common theme in Italy’s attacking game is their dependence on passing combinations in wide areas and rotations between the players in those spaces, regardless of the shape.

Their key player(s)

After an impressive season with Inter, Barella is entering Euro 2024 as his country’s shining light. The midfielder’s ability to win back the ball in midfield and help the team defensively strengthens Spalletti’s side without the ball, but it’s his technical ability and the options he provides in possession that make him crucial to this side.

Barella constantly drops to help Italy build up the attacks, while also supporting the passing combinations out wide with his precise passing and off-ball movement. The latter is another feature of his game that allows him to be an offensive threat in the opposition penalty area with late runs from midfield.

(Adam Hunger/Getty Images)

What is their weakness?

Once Italy lose possession, they look vulnerable on defensive transitions. They leave large spaces between their defensive line and the rest of the team. Rashford’s goal in the 3-1 loss against England last October is a scene that Spalletti would preferably avoid in the upcoming tournament.

The back-three formation has provided more central cover when Italy are transitioning from attack to defence, but it’s still an area that opponents can exploit.

One thing to watch out for…

Italy’s corner threat.

Throughout the qualifying matches and in their recent friendlies, Italy’s attacking corners have been one of their main offensive solutions. In terms of expected goals (xG) per 100 corners — which allows us to level the playing field when comparing across teams — their rate of 5.7 was the sixth-best of the 53 nations that competed for a place in this summer’s tournament.

- Manager: Zlatko Dalic

- Captain: Luka Modric

- Qualifying record: P8, W5, D1, L2, GF13, GA4

- Euro 2020: Round of 16

- Most caps in squad: Luka Modric (175)

- Top scorer in squad: Ivan Perisic (33)

How do they play?

There’s not much deviation from how Croatia have been playing under Dalic in previous tournaments.

They still set up in a 4-3-3 formation, and they are still built around the midfield trio of Marcelo Brozovic, Mateo Kovacic and Luka Modric, with flying full-backs as prominent as ever down the wings. However, matches against Armenia and Latvia showed they can mix it up by playing Andrej Kramaric as a No 10 in a 4-2-3-1.

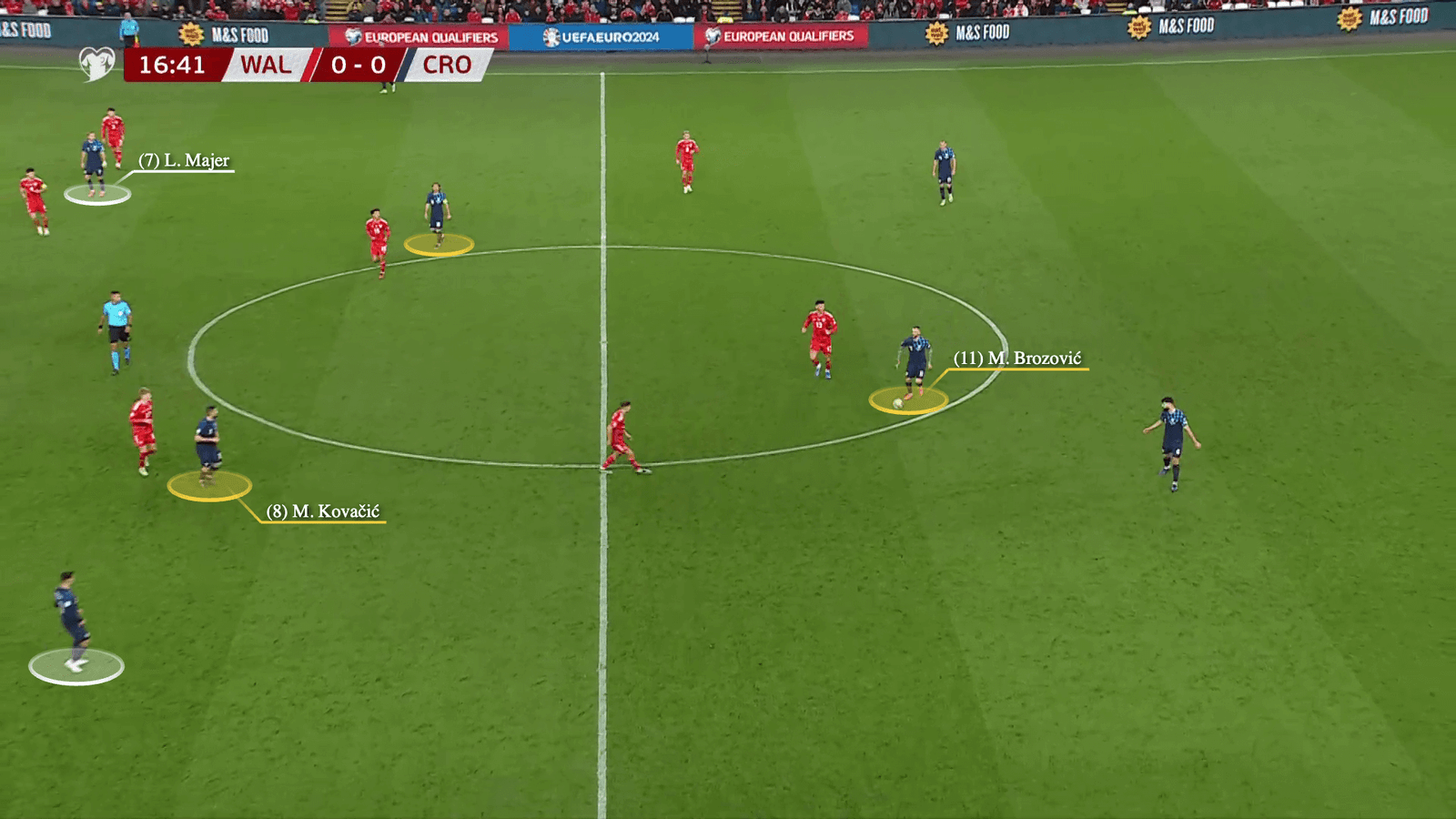

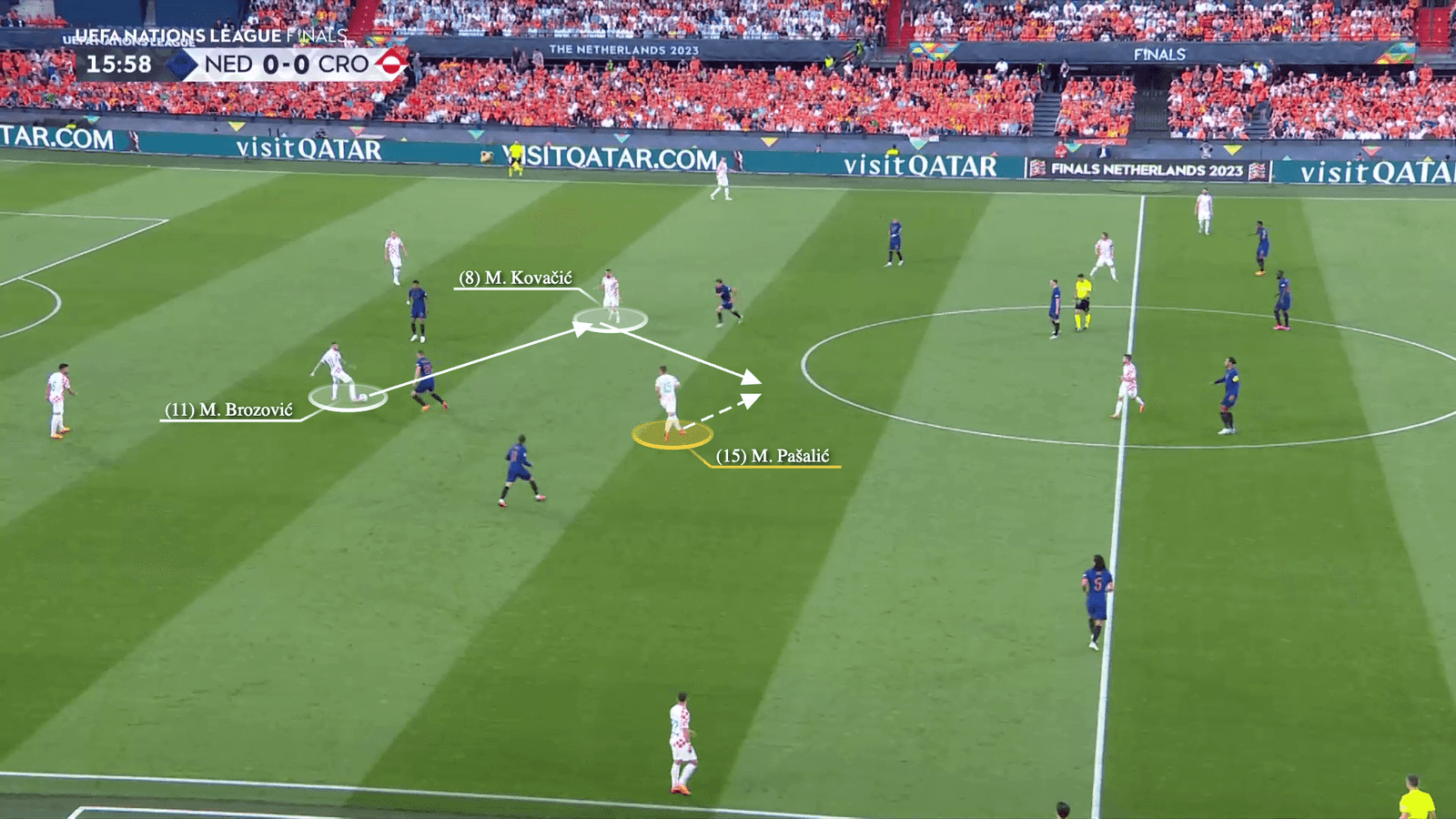

Croatia’s possession game is mainly built on the technical abilities of Brozovic, Kovacic and Modric. The experienced trio drop deep to control the game with the ball.

Their fluid movement, passing combinations and interchanging of positions allow them to play through opponents and progress the ball into the final third. In front of them, the front three usually occupy narrow positions to present themselves as passing options to the midfielders…

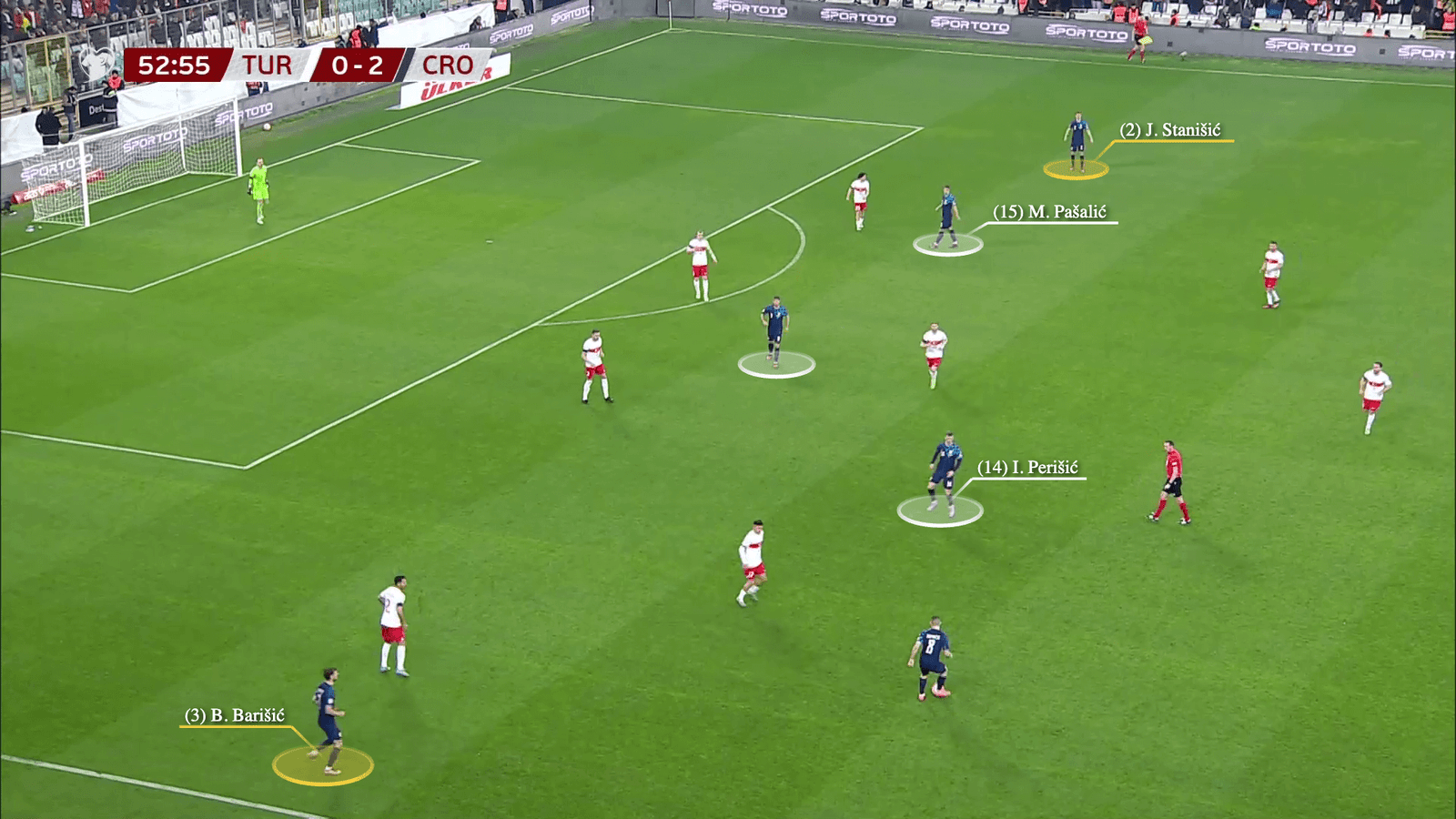

… and create space for the full-backs to attack. In this example, from the 2-0 victory away to Turkey in March 2023, Borna Barisic and Josip Stanisic are high up the pitch, flanking a narrow front three of Ivan Perisic, Kramaric and Mario Pasalic.

Earlier in that game, Josip Sutalo’s long pass into the advanced right-back Stanisic had led to the opener.

Here, Pasalic’s narrow positioning occupies Turkey’s left-back, and Sutalo finds Stanisic’s run behind the defence, before the right-back plays the ball into Pasalic. Meanwhile, Kovacic is making a late run into the box and the ball falls into his path after Perisic and Pasilic fail to find a shooting angle. The City midfielder doesn’t hesitate and scores to make it 1-0.

The profiles of the players playing in Croatia’s front line complement their tactical approach. When Kramaric starts as the side’s centre-forward, his movement and link-up play allow him to drop and overload the midfield.

In addition, choosing Lovro Majer or Pasalic to play as the team’s right-sided option rather than an out-and-out winger means Croatia can overload the central areas and use Majer or Pasalic to play through their opponents.

Their key player(s)

Croatia’s midfield of Kovacic, Brozovic and Modric is a trio that most nations dream of, even if they are into their thirties. Together, they provide a balance of technical ability, press resistance, ball carrying, athleticism and defensive quality.

On top of that, their experience at the international stage will be needed. Brozovic (96 caps) and Kovacic (101) are among the wiliest players at the tournament, while Modric (175) is the country’s most-capped player of all time. After guiding their team to third and second place in the two most recent World Cups, they will be hoping to emulate that success in a European Championship.

What is their weakness?

The four goals Croatia conceded in their eight qualifying matches could had been more — their non-penalty xG conceded was 6.4. At times, their back line has been porous — defenders made mistakes and Dominik Livakovic’s saves were important.

The Fenerbahce goalkeeper registered a ‘goals prevented’ figure of 2.3 in Croatia’s qualifying campaign. There are ways past this side’s defence, but the hard part is beating Livakovic.

One thing to watch out for…

In their last six penalty shootouts, Croatia lost only once (in the 2023 Nations League final against Spain). Their shootout victories helped them progress at the 2018 and 2022 World Cups, beating Denmark and Japan in the last 16 and Russia and Brazil in the quarter-finals of the two tournaments respectively.

In the last World Cup, Livakovic saved three penalties against Japan’s Takumi Minamino, Kaoru Mitoma and Maya Yoshida, before stopping Brazil’s Rodrygo in the following round. If Croatia advance to the knockout stage in Euro 2024, their continuing record in the shootouts is something to keep an eye on.

- Manager: Sylvinho

- Captain: Berat Djimsiti

- Qualifying record: P8, W4, D3, L1, GF12, GA4

- Euro 2020: Did not qualify

- Most caps in squad: Elseid Hysaj (84)

- Top scorer in squad: Rey Manaj (Eight)

How do they play?

Unlike the rest of Group B, Albania favour a more direct approach on the ball. Playing out of a 4-2-3-1 shape, Sylvinho’s team play to their centre-forward with long passes to flick on to one of the wingers and fight for second balls.

Their other option for moving the ball up the pitch are direct passes to their wide players, Jasir Asani and Taulant Seferi, which come in the form of quick deliveries from the full-backs, or diagonals from the centre-backs and midfielders.

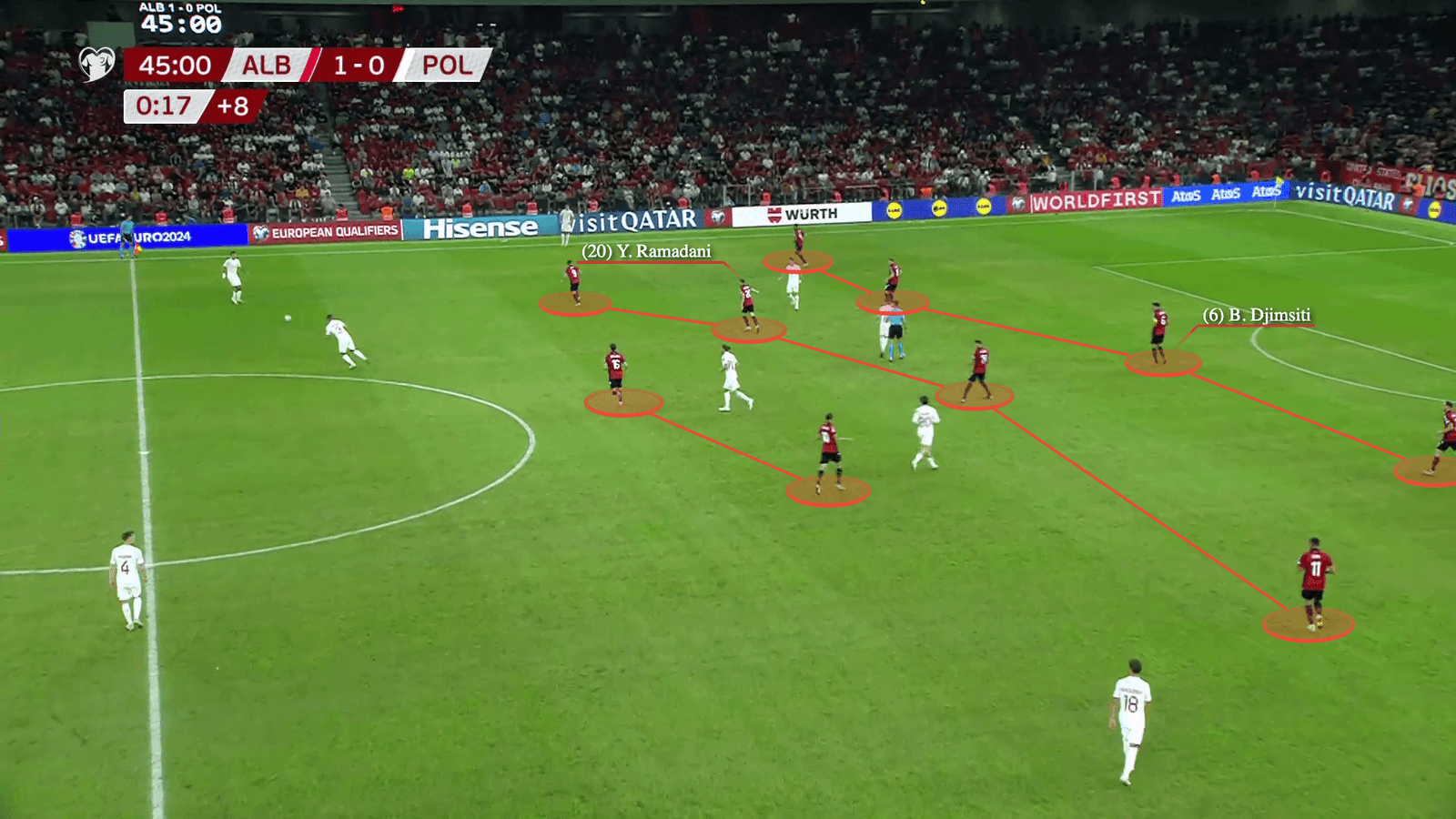

Off the ball, Albania drop into a medium-low block in their own half, with the experience of Djimsiti and Hysaj essential to their defensive organisation. However, they are a proactive side in this situation — always on the front foot and looking to win the ball back as quickly as possible in their own half to start the counter.

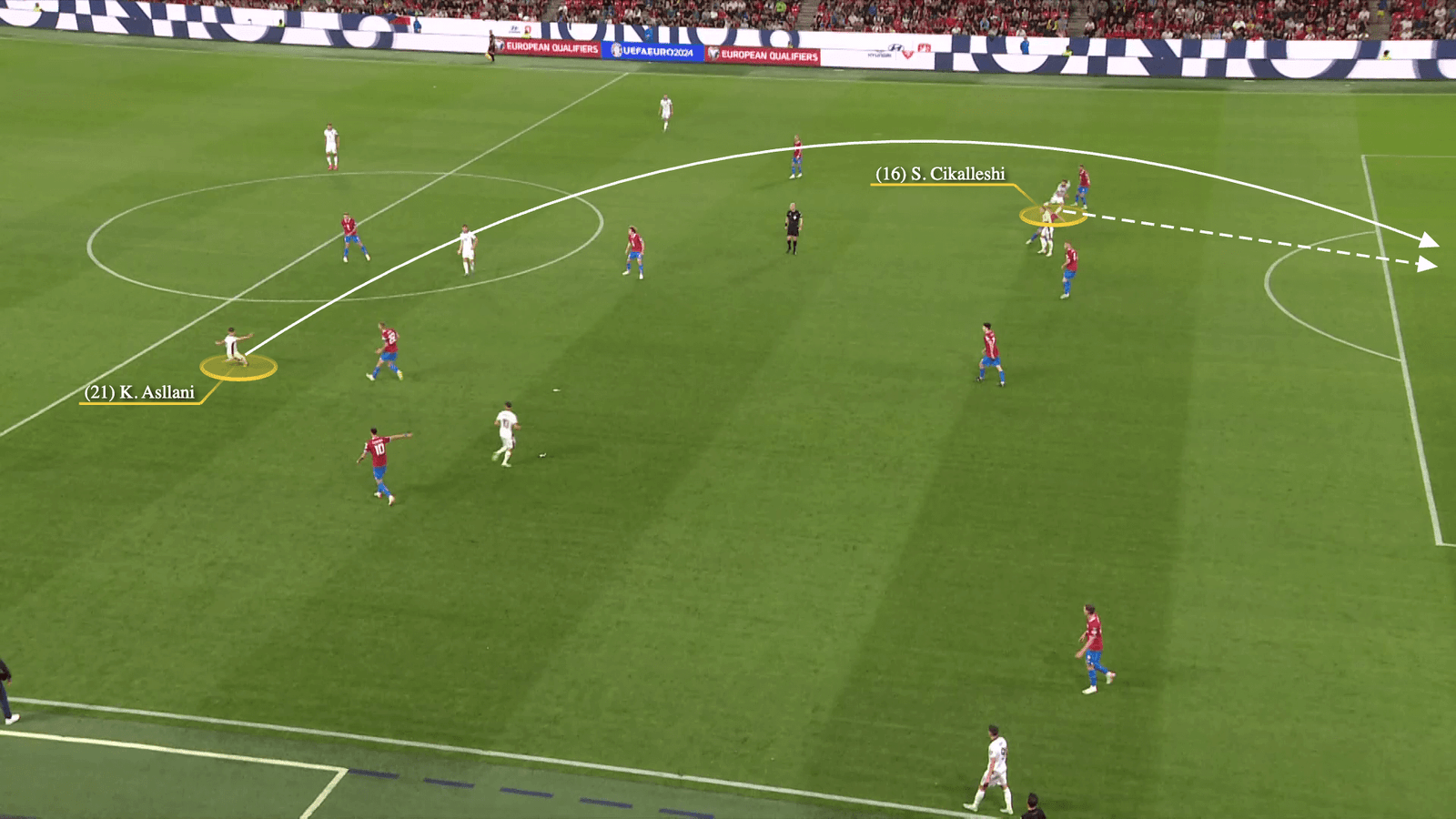

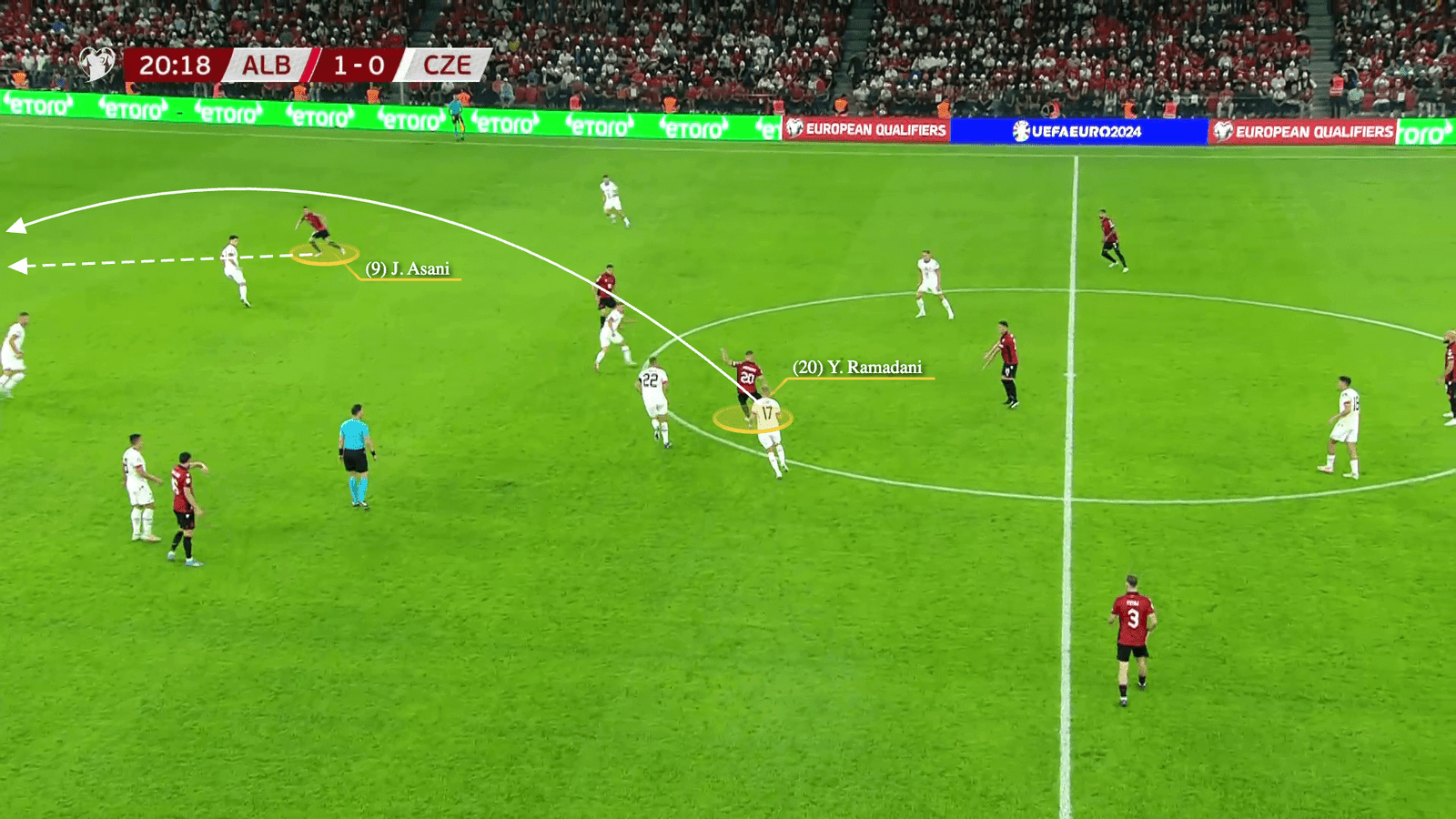

Once they win possession, the pace of the wide players, Nedim Bajrami’s ball-carrying ability, and the accurate passing of Kristjan Asllani and Ylber Ramadani make Albania a threat on attacking transitions.

Asllani and Ramadani’s vision and passing ability empower the forwards’ runs behind the defence, which is a feature of how this Albania side attacks the opponents.

Their key player(s)

Ramadani and Asllani, Albania’s double pivot in midfield, are the complete package. The duo’s defensive positioning supports the defensive line and allows Sylvinho’s side to retrieve possession in the middle of the pitch. Their defensive awareness is complemented by their smart positioning when Albania are in possession of the ball — constantly adjusting their positions to provide passing options for their defensive line — and their ability to receive the ball with their back to the goal. Asllani, in particular, knows how to use his body to shield the ball, which makes him harder to dispossess.

Down the right wing, 29-year-old Asani, who was called up to the national team for the first time in March 2023, was one of Albania’s most impressive players in the Euro qualifiers. The winger’s dribbling ability gives him an advantage in one-versus-one situations to use his best asset, which is ball striking. Asani finds team-mates with inch-perfect passes, and his trademark finish is cutting inside before finding the far corner.

His goal against Poland last September is a glimpse of what he can do when he is allowed to shoot.

Asani 🤯#EURO2024 pic.twitter.com/adRYoI0QN7

— UEFA EURO 2024 (@EURO2024) February 19, 2024

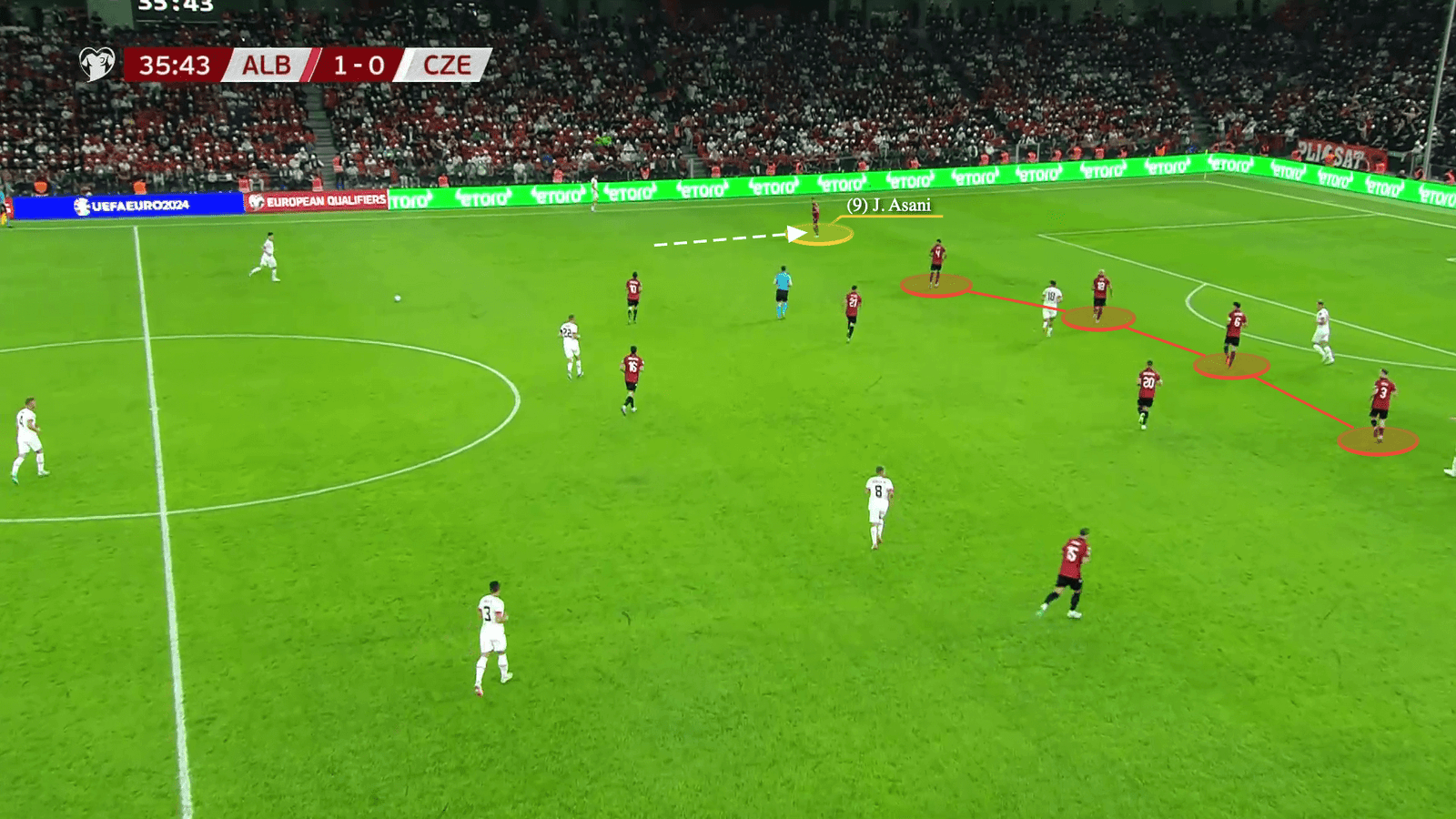

Normally, players of this profile are a burden on the defensive side of things, but Asani regularly tracks back to support his right-back, Hysaj. In the two games against Czech Republic last autumn, Sylvinho used Asani as a situational wing-back when Albania were in the defensive phase to prevent Czech Republic from overloading their back four.

What is their weakness?

Despite the experience of their defensive line, Albania’s front-footed defending in their own half could be vulnerable against three sides who excel on passing combinations and off-ball movement.

Albania’s 0.78 non-penalty xG conceded per game in the Euro qualifiers will be tested against stronger opponents who have the collective and individual tools to break down defences and score from difficult situations.

One thing to watch out for…

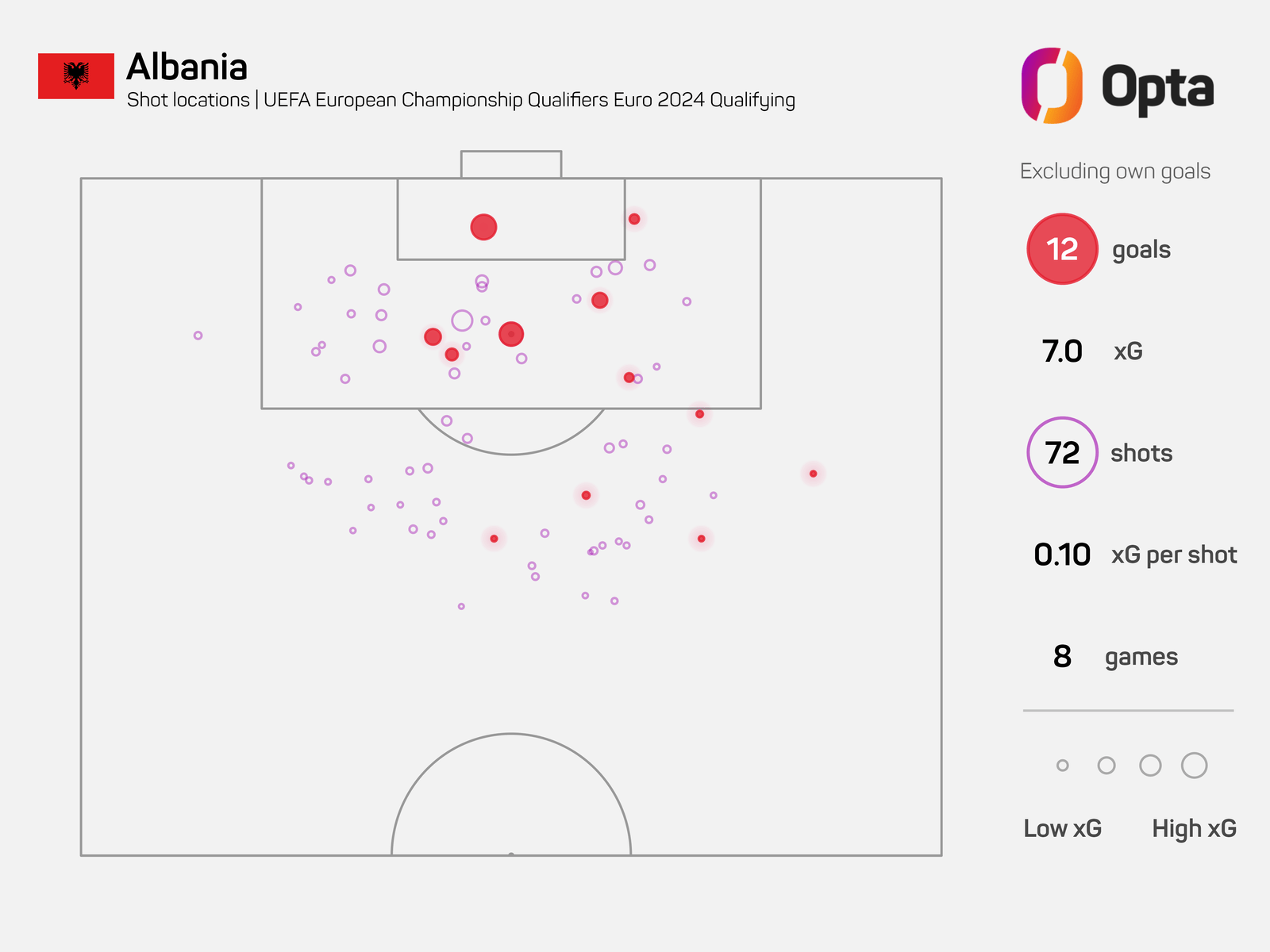

Long-range shots.

Five of Albania’s 12 goals in the Euro qualifiers came from outside the penalty area, which partly explains their xG overperformance.

In addition to Asani’s three strikes against Moldova, Poland and Czech Republic, Asllani and Bajrami also scored important goals from distance on Albania’s road to Euro 2024.

Sylvinho’s team isn’t the most complicated attacking unit, and goals from individual moments of brilliance could get Albania in the lead and let them play a favourable game state, where they can drop deeper and attack on transitions.

Fixtures

Round 1:

- 15/06/2024 — Spain vs Croatia (6pm CEST, 5pm BST, 12pm EDT)

- 15/06/2024 — Italy vs Albania (9pm CEST, 8pm BST, 3pm EDT)

Round 2:

- 19/06/2024 — Croatia vs Albania (3pm CEST, 2pm BST, 9am EDT)

- 20/06/2024 — Spain vs Italy (9pm CEST, 8pm BST, 3pm EDT)

Round 3:

- 24/06/2024 — Albania vs Spain (9pm CEST, 8pm BST, 3pm EDT)

- 24/06/2024 — Croatia vs Italy (9pm CEST, 8pm BST, 3pm EDT)

(Header design: Eamonn Dalton, photos: Getty Images)

Read the full article here