Ollie Watkins was the difference maker in England reaching the Euro 2024 final.

He walked off the pitch in Dortmund overcome with emotion and a picture of realisation. His strike in the 90th minute was the culmination of a yearning desire for self-improvement and a storied career that started at Exeter City, in the lower leagues of English football. It has featured a loan spell at sixth-tier side Weston-super-Mare, a climb up the ladder at Brentford before, at Aston Villa, becoming an international forward and one of Europe’s most lethal strikers.

His goal — a trademark finish, as you will see below — against the Netherlands was an echo of his club form and years of hard work. Watkins was the first player in Europe’s top five leagues to score 15 goals and register 10 assists last season. A combined Premier League total of 32 — 19 goals and 13 assists — meant the 28-year-old was only the ninth English player in the Premier League era to have 30 or more goal involvements in a 38-game campaign.

The finish. The roar. The celebrations. 😍pic.twitter.com/y8S6lmrcOf

— England (@England) July 11, 2024

Since joining Villa, Watkins has 86 goal contributions — only Mohamed Salah, Son Heung-Min and Harry Kane have had more in the Premier League in that time. From forwards across Europe’s top five leagues last season, the 28-year-old ranked in the top three per cent for assists per 90 minutes (0.36) and the top two per cent for goal-creating actions (0.73).

In short, his evolution has been remarkable.

This is the experience of marking Watkins, told by former team-mates, coaches, opposition from every step of the footballing ladder he has played at, and also the player himself.

The Athletic has spoken to:

| PLAYER | CLUB THEY WERE AT |

|---|---|

|

Danny Butterfield |

Team-mate and mentor at Exeter |

|

Tom Jordan |

Team-mate and Weston-super-Mare defender |

|

Peter Hartley |

Plymouth Argyle defender |

|

Lars Friis |

Brentford’s development coach |

|

Grant Hall |

Queens Park Rangers defender |

|

John McGinn |

Aston Villa captain |

|

Jordan Henderson |

Ajax midfielder and England team-mate |

Impact

On March 25, 2021, Watkins scored on his England debut in a 5-0 victory against San Marino. His goal drew a moment of reflection, having signed his first contract at Exeter seven years earlier. Exeter had turned him away following a trial aged nine.

Danny Butterfield: “After Ollie scored against San Marino, he texted me. I used to do finishing sessions where I would get him to shift and shoot through the defender’s legs. When a defender would stretch to block the shot, Ollie would reverse it back through their legs. His goal was just like that. When he scored, I was sitting on the sofa with my son and he was on his phone as usual. I screamed and scared him.

“Ollie texted, ‘I remember you doing those sessions with me’. Back then, I would speak about Cristiano Ronaldo and say to watch him. But a funny one I said to Ollie — forgetting how old he was — was to watch John Barnes in one-on-one situations. Ollie would just say ‘Who’s John Barnes?’.”

In December 2014, Watkins joined Weston-super-Mare on loan. He scored 10 goals in 25 appearances.

Tom Jordan: “When he first came, he wasn’t the presence he is now. Believe it or not, we tried to play good football, so he suited us because he had good technical attributes. But when you’re playing non-League and we were up against it — losing more than we were winning — he was doing his best to make bad balls good.

“He was learning the other side of the game of chasing things down and battling against bigger, more seasoned men. He didn’t have it easy.”

Despite early reservations, Watkins began to flourish in League Two, going on a run of eight goals in 10 games, with two coming in a late comeback victory against Plymouth Argyle in the Devon derby in April 2016. Watkins’ second was voted Exeter’s goal of the season.

Peter Hartley: “He was a 20-year-old kid and we were winning 1-0. But he scored twice. I’ve never seen a kid so sharp. It has happened twice in my career where I’ve had to hold my hands up and walk off the pitch thinking, ‘Wow, he was too good for me’. Once against Celtic with Odsonne Edouard. But that day against Watkins I just thought, ‘You’re too good for me’.

“All of us looked at each other afterwards. Me, Curtis Nelson, Reuben Reid. We sat and thought ‘Oh my god, this guy is a different animal’. Ollie had come from nowhere — I’d never heard of him. It honestly felt we should have said, ‘Three cheers for Ollie’, and got on with it.”

Ollie Watkins vs Plymouth

2nd April 2016

After a Luke McCormick howler it was 1-1 & virtully the last kick of the game. Ollie picks up the ball on the halfway line, beats 2 players & fires a rocket from his weakfoot, flying into the top corner to win the Devon Derby 2-1! #ECFC pic.twitter.com/2akCJwWv9a

— Exeter City (@ECFCStats) June 9, 2018

Attitude

Jordan: “He bought into what we were doing. When lads are loaned to you from Football League clubs, they often turn up and think, ‘I’m better than this’. It’s cold showers, muddy pitches and boys arrive in vans because they’re tradesmen.

“But he trained wanting to get something out of each session. To play against, he was always looking at the goal. Whenever the ball was played into him, he was trying to shift and shoot all the time. Ollie is two-footed, which was rare and a nightmare. Normally defenders work out what side strikers are weak, but Ollie was hungry to shoot off both feet. That stood out.”

Hartley: “Sometimes as a centre-half, when you can’t get near someone or you see someone being a little bit cocky, you leave one on them. I did it with Dominic Calvert-Lewin when he played for Northampton Town and he disappeared. But he was young. I did the same with Ollie and he came back and wanted more. I just thought ‘Wow, this guy is relentless’. You could see he was technically gifted and a step before everybody in his head.

“You try to intimidate young kids, especially when they’ve got a yard on you. He’s one of those players where you get tight and he spins you. So you drop off and because he’s so intelligent, he will check his shoulder, turn, and run at you. I thought, ‘He’s a step ahead of me, so I’m going to have to leave one on him’. But he got up, laughed and went again. I didn’t talk to him — partly because I couldn’t get near him.”

Grant Hall: “Brentford were a dominant possession team and you’d want to let them know you’re there early doors. It never seemed to faze him. He’d be a threat the whole time.”

John McGinn: “Previously he would be very hard on himself, desperate to score, to be perfect. It’s impossible to be perfect in this league, it’s impossible to be perfect if you’re an England striker. He’s got a big cheeser (cheesy smile) and he gets a cheeser when he scores. His mentality has changed, he’s not so hard on himself.”

Coachability

Butterfield: “A lot of the work done with Ollie wasn’t coach-driven but by himself. He would do an extra 15-20 minutes after training.”

Jordan: “There were occasions he would get frustrated because of your old-fashioned channel ball — playing non-League football as a centre half, getting the ball out of your feet and turning the opposition defence round was common. But he’s a quick learner. So once I stuck one or two in behind, he would run.

“He had a good attitude to the mixed service he was receiving. He didn’t show any negativity. The only time I saw him frustrated was when he didn’t start. When the manager (Ryan Northmore) rotated, Ollie knocked on his door.”

Positional evolution

Butterfield: “He was a left-winger cutting in on his right at youth level. Even on debut away to Plymouth, he played left of a midfield diamond. It wasn’t until later he moved to centre-forward or slightly deeper centrally.

“Because he was so effective in one-v-ones when I played right-back in training, I would call someone to double-up. I used to speak about Ronaldo to Ollie. When he received the ball and it was a one-v-two and the full-back was doubling up, Ronaldo would release it or play one touch and wait for the ball to come back to get his one-v-one scenario, so he could take on an individual as opposed to being doubled up.”

Jordan: “He played mostly on the left at Weston. He was quite slight, which made it easier playing on the wing because he wasn’t getting everything back to goal against centre-halves. We were in a 3-5-2 and he operated as a wide forward.”

Hartley: “He was off a focal point No 9 at Exeter. Ollie was in the hole and driving, using his pace with the ball. Now at Villa, he’s more on the shoulder, exploiting the space behind (as can be seen from his touch locations below).

“He was difficult to mark because he had free rein. He was very good when we had the ball because he just stood in space. As soon as a transition happened, bang, he was in space to receive the ball. He would gravitate towards the wing and that was his trigger to do a stepover and come inside. That’s how he scored his two goals against us.

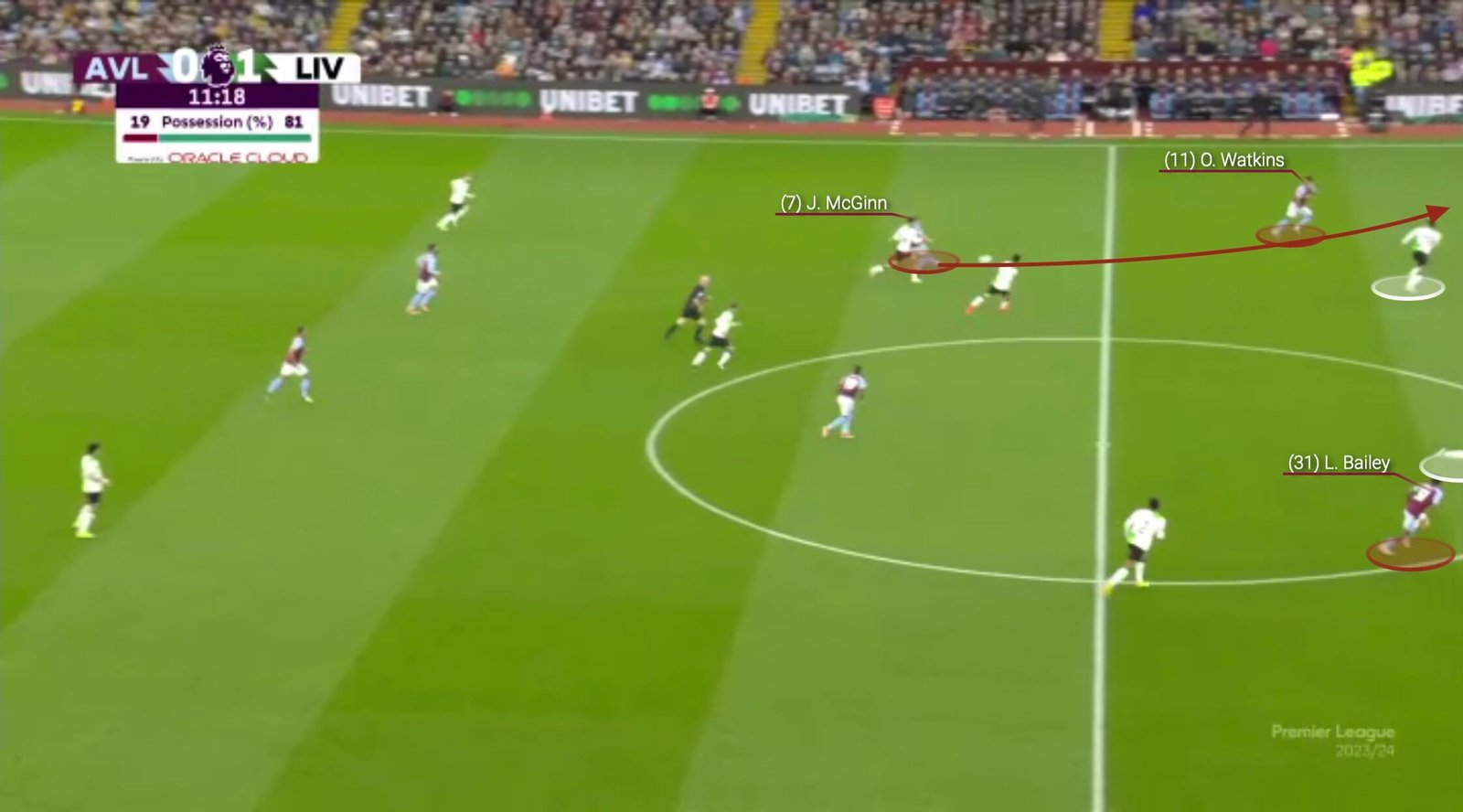

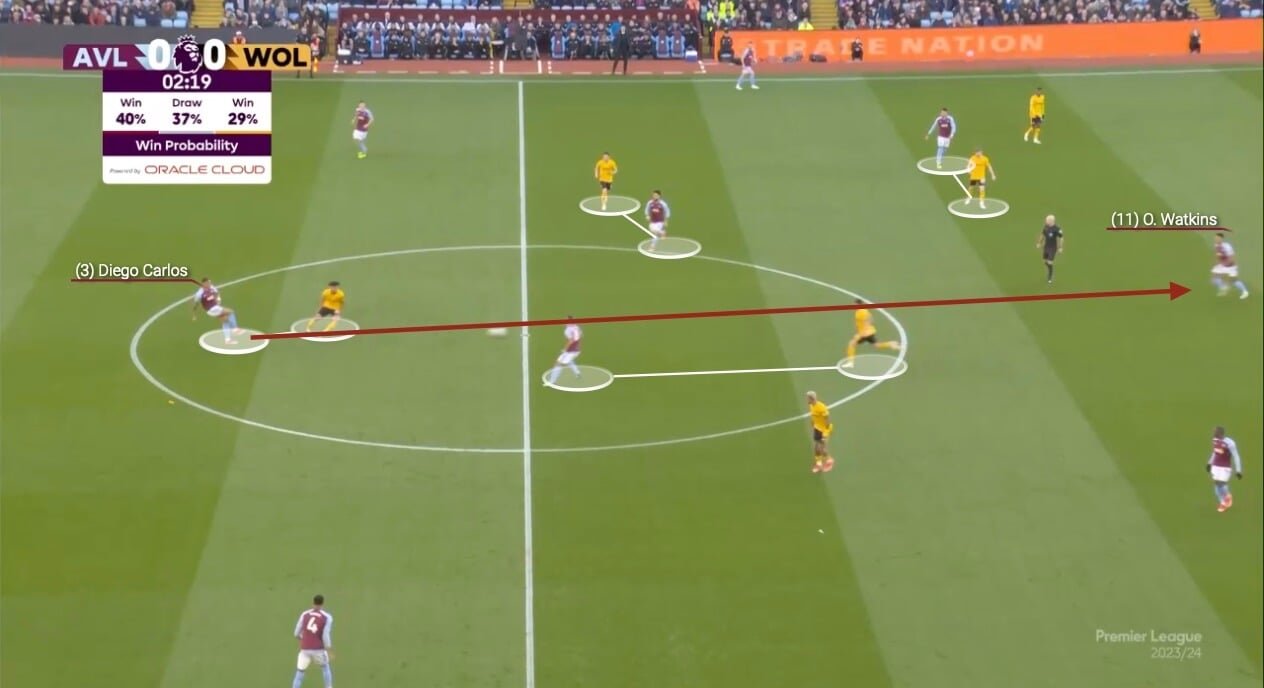

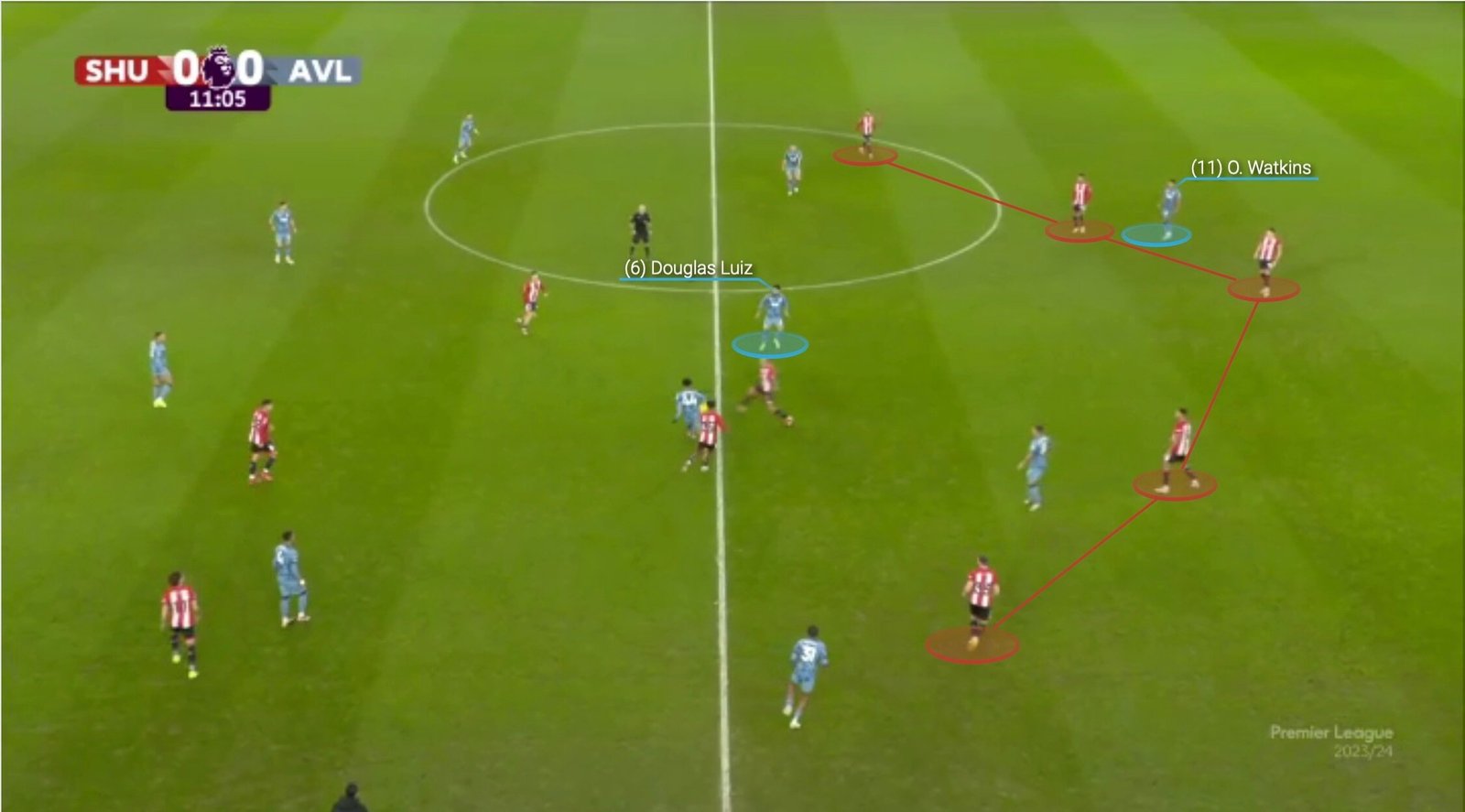

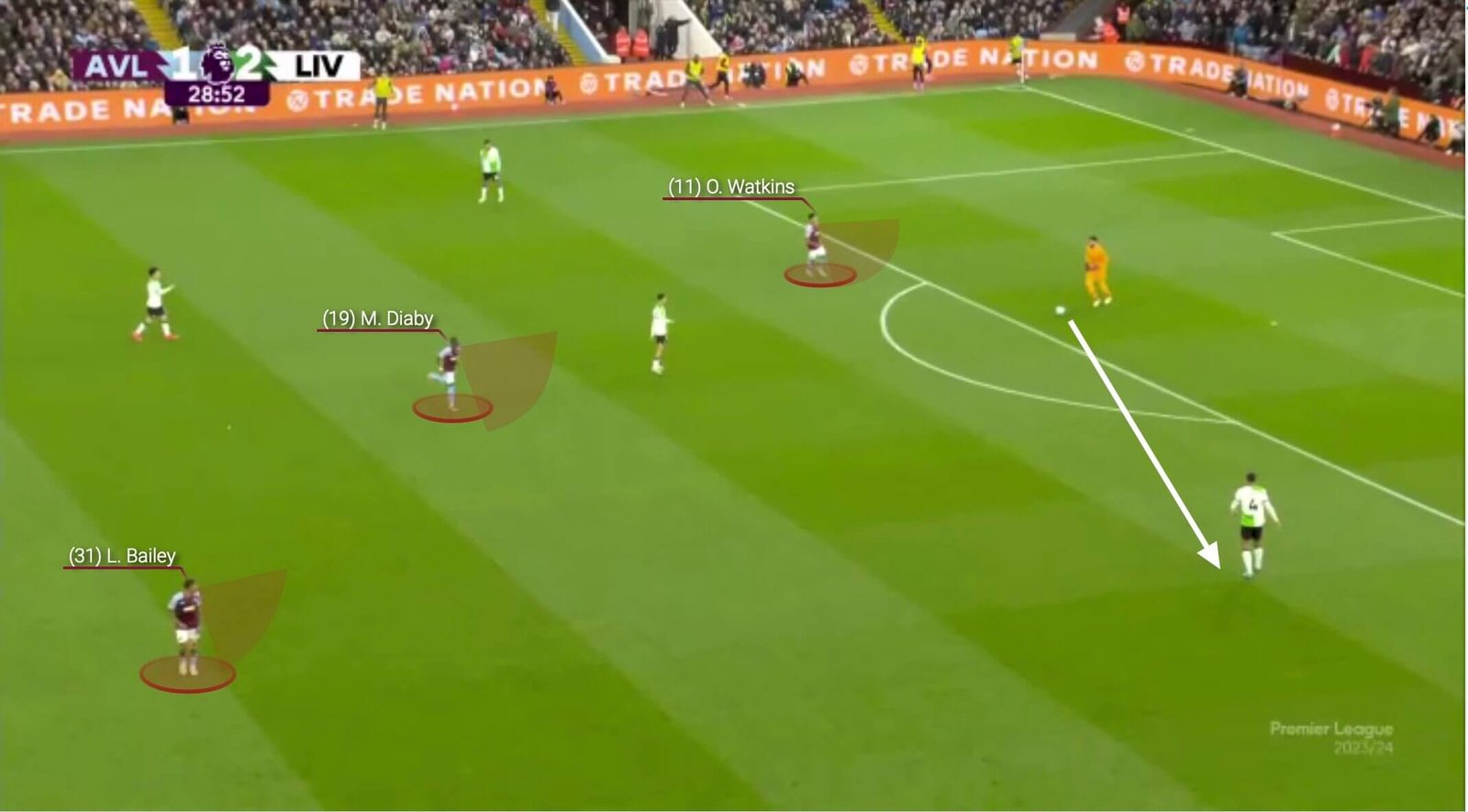

“You’re constantly checking your shoulder because Watkins is between you and your full-back. You see how Villa play — Leon Bailey is on the right and he holds the width, pulling the full-back out to create the space for Watkins in between the centre-back and opposite full-back (take the example below from their game against Liverpool).”

Lars Friis: “His forward runs were very good. With space, he was dangerous with and without the ball. At the beginning with Brentford, he played as a winger and occasionally as a No 9. It was a front three but gradually, Watkins went up alongside Neal Maupay.”

Hall: “Before Brentford came to Loftus Road, we had meetings and he was one of their main players alongside (Said) Benrahma and Maupay. The problem for me was that Ollie wasn’t an out-an-out striker like he is now at Villa, he would drop into the No 10 position.

“Normally I’d go in deeper positions with him, but it was tough because if Maupay was making runs in behind, I had to make a decision. The striker that drops in is the hardest to deal with.”

In October 2019, Watkins scored twice against QPR in a 3-1 victory. He became Brentford’s quickest player to 20 league goals since 1977, with his adaptation — from Exeter’s floaty wide forward to a dovetailing striker — on track to becoming a rounded No 9.

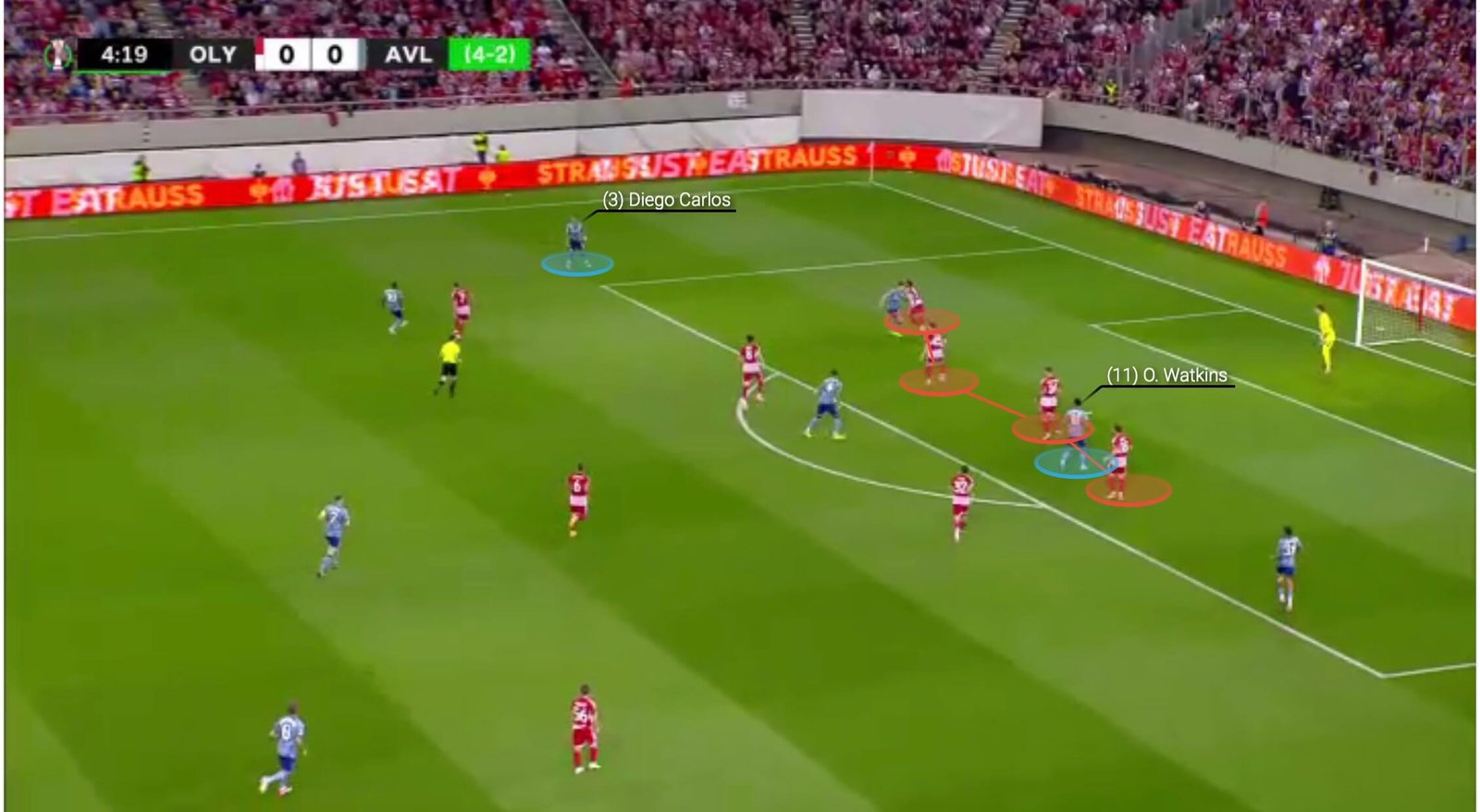

Hall: “His first goal was from a cross. It was my fault, I was upset I’d lost him. It was a clever little movement, pulling off my shoulder for a split second and that was it — goal. He initially feinted to go to the front post and made sure he would be in my peripheral vision.

“When I stepped forward, anticipating his near post run and took the step, he saw and pulled behind me. He was between me and Toni Leistner in a great position.

“It was tough because he had such good movement — he would make double movements and would react off where I stepped, which is so difficult to pick up.”

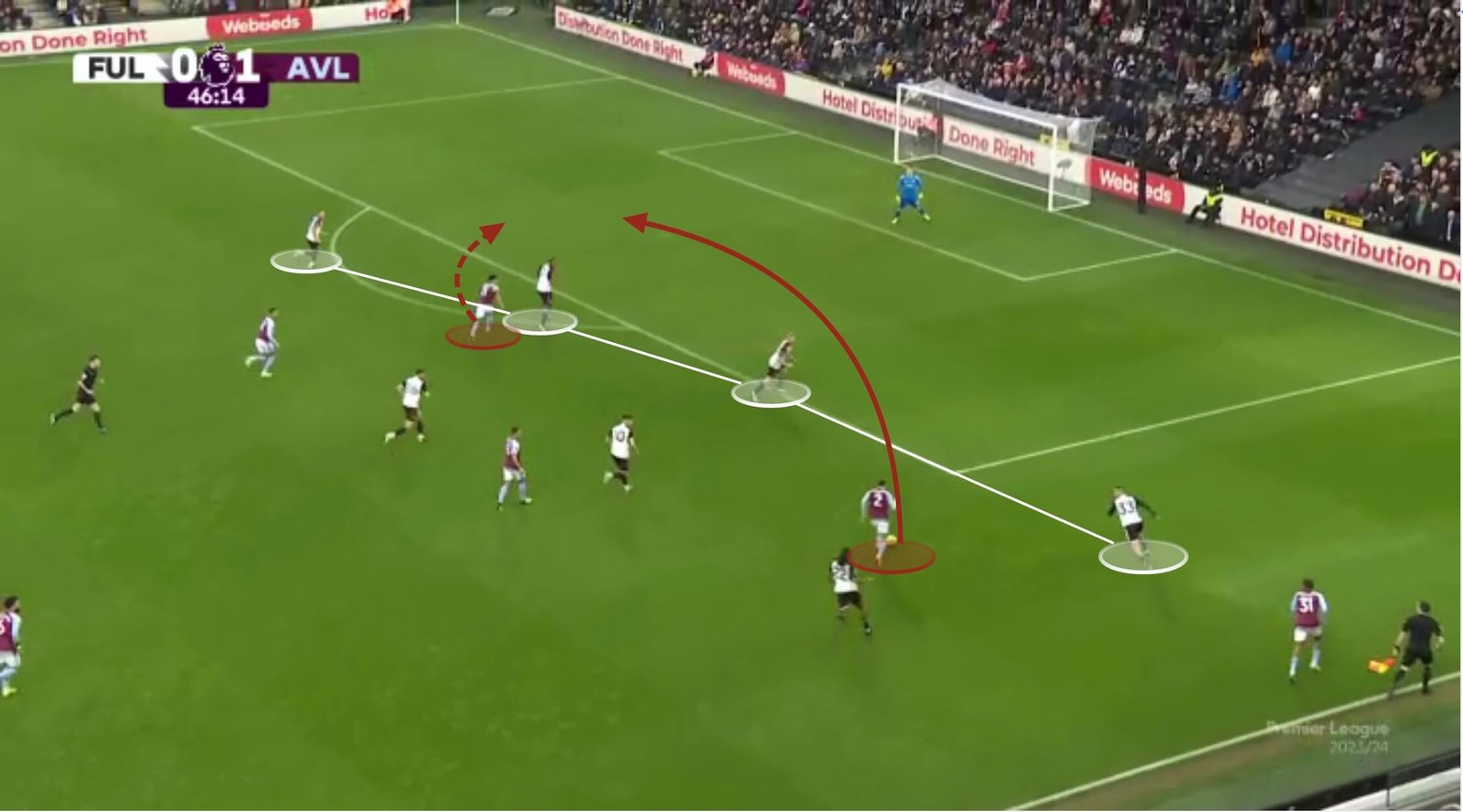

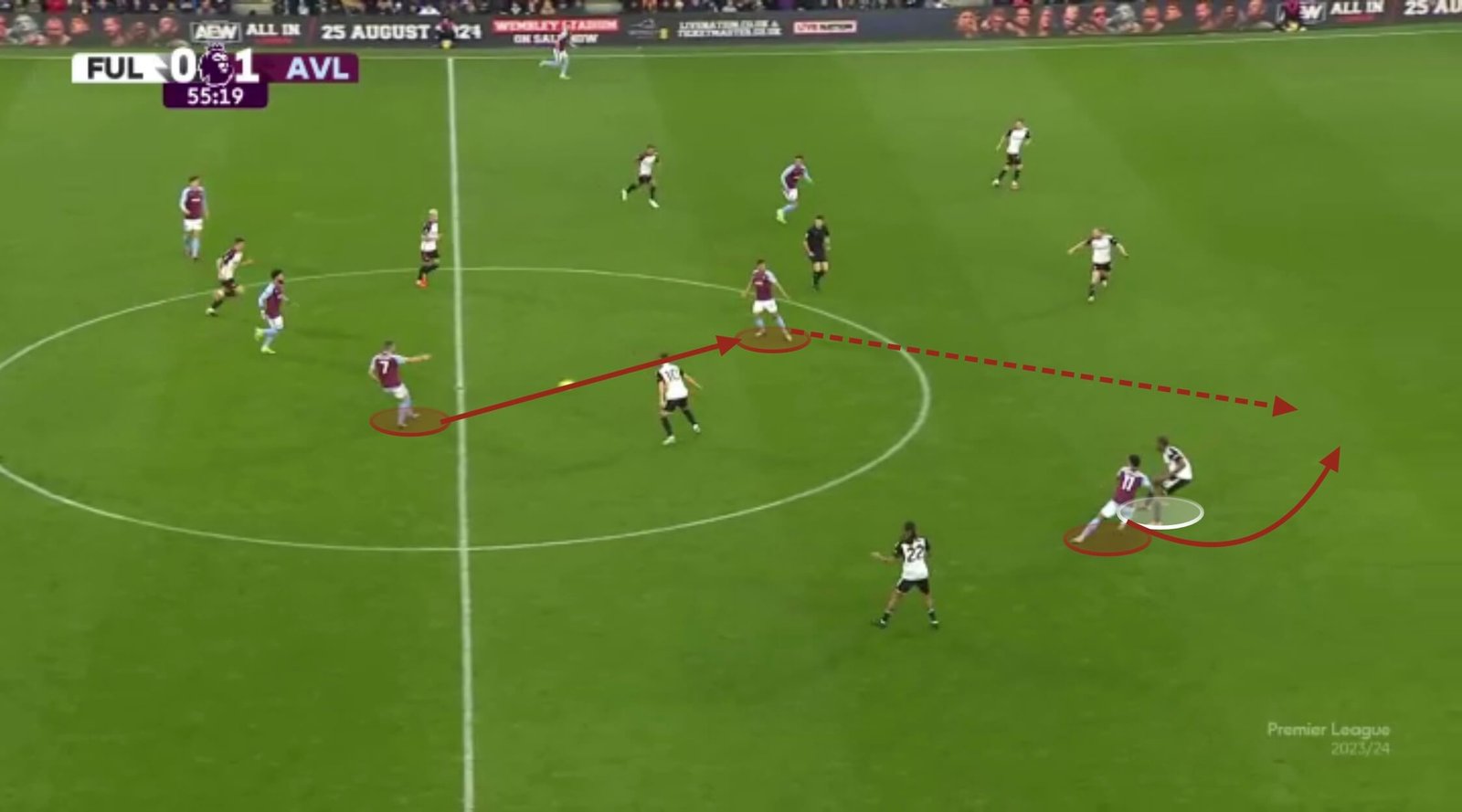

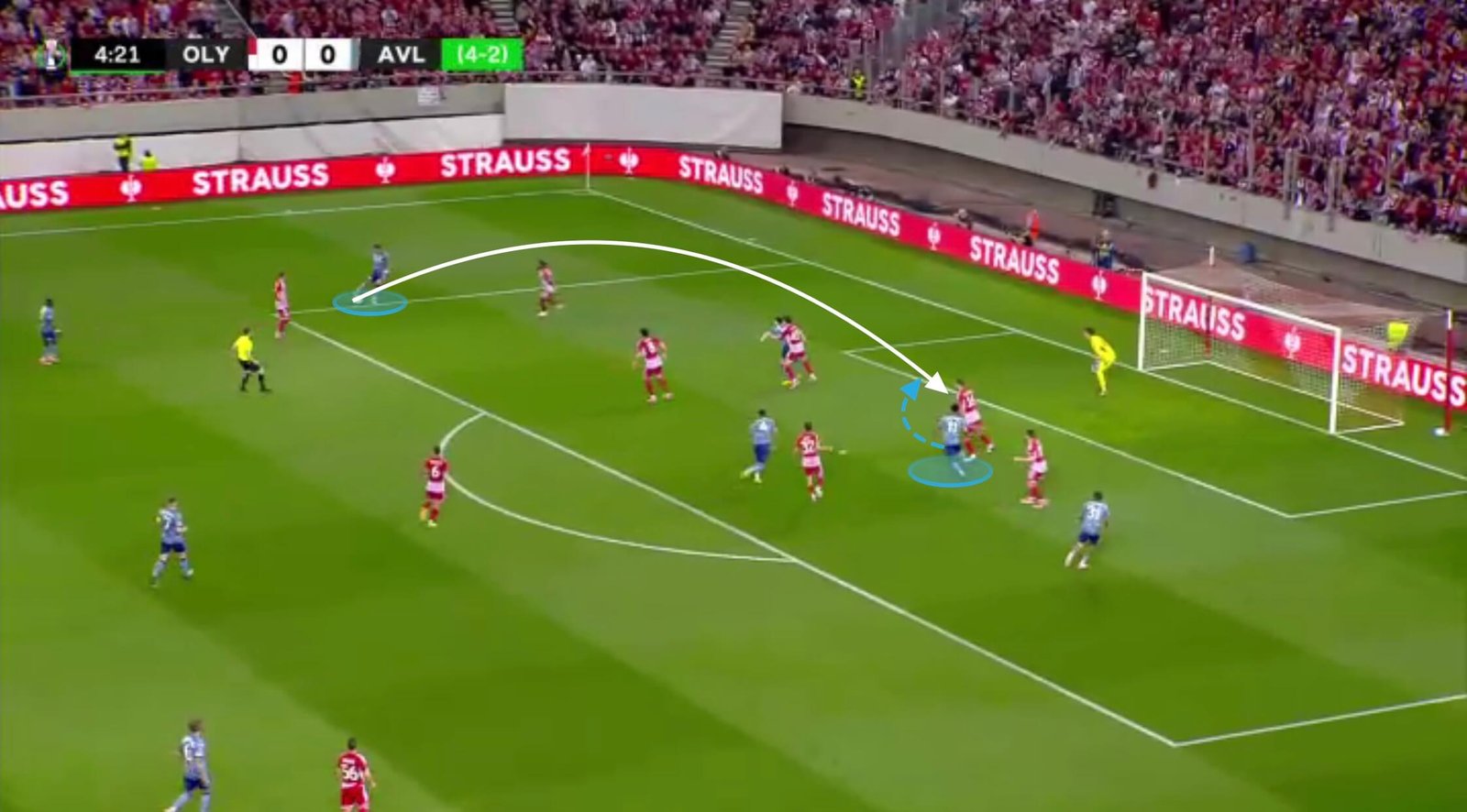

Against Fulham last season, Watkins made a similar run, staying between the two centre-backs having feinted to run towards the near post.

When the cross is delivered, Watkins peels off the furthest centre-back and instead aims for the far post.

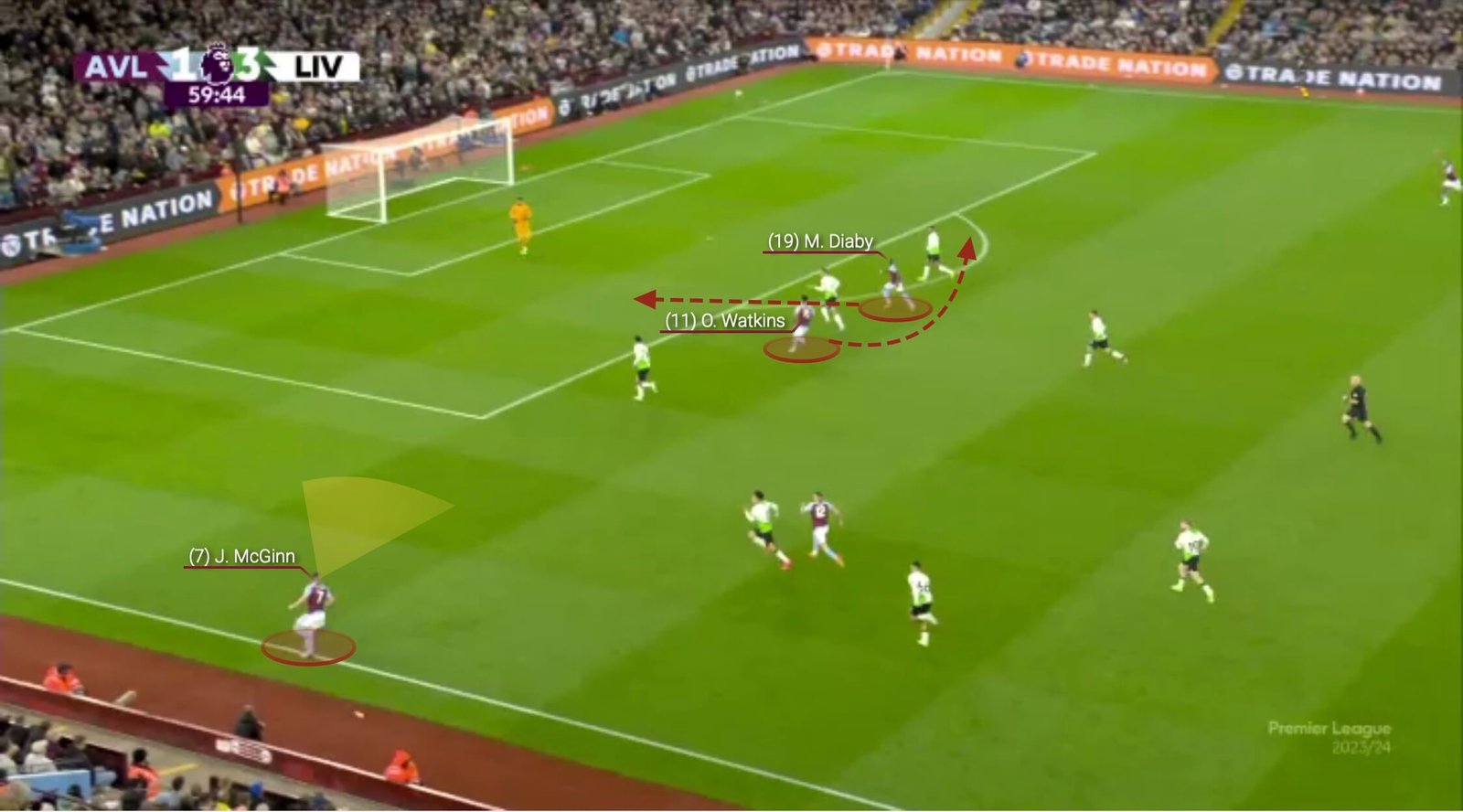

From a wider position, Watkins replicates this movement against Liverpool:

Movement: blind-side running and double movements with pace

Butterfield: “We needed to convince him he couldn’t always be the wide man waiting for the ball to his feet. He needed to get involved in second balls, run behind and take out the right-back with his movement. He went through tough patches when he went to Weston and he was close to going on another loan because he was becoming frustrated. Our manager, Paul Tisdale, was questioning it.”

Jordan: “He had good feints. His movement was good, but the players around him weren’t recognising it. His learning was about the ugly side at Weston. Probably the further he went up the pyramid, the more players were finding him in space.”

Friis: “His standout attribute was his pace. His directness comes from his mindset in running with and without the ball. It’s so physically hard, knowing you work to your max and don’t always receive the ball, but he was direct and selfless.”

Hall: “What set him apart was his pace. He would drop in and spin, although he does it more with Villa now. That spin is the best movement to get behind defenders.”

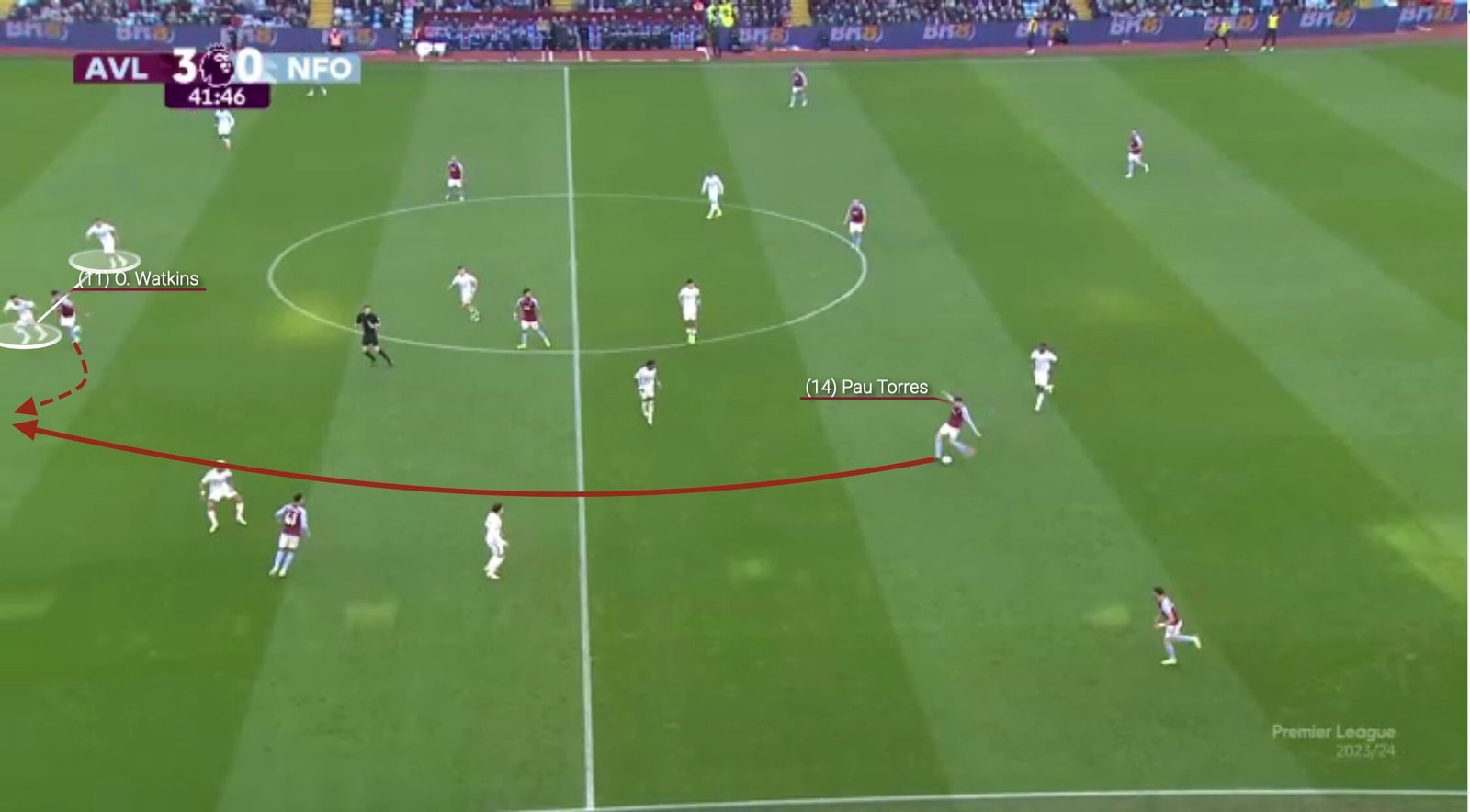

Butterfield: “Out-to-in runs to receive between the centre-back and right-back were key, but so was the double move. When he was out wide and his full-back had the ball, Ollie would come towards it and plant his foot before spinning. Crucially, Ollie began doing the opposite movement, running behind to then receive the ball to feet. He does it for Villa all the time.

“We did a lot of sessions where it was one-v-one, two-v-two and put rules in where you couldn’t receive to feet — you had to receive behind. It was about making runs, staying onside and linking with a team-mate.

“We created zones where you receive to feet, while the other player received beyond. We would encourage him that even when play broke down, he still ran behind. If he did, he would stay on, whereas if he didn’t, he would go out to practise and someone took his place. This gave him an incentive to make those runs.

“Villa score a lot on on the counter. Ollie is running and Bailey’s down the right. Ollie will decide whether to drag the closest marker to the near or far post, allowing Bailey to isolate his defender.”

Jordan Henderson: “Ollie is an outstanding player. He has everything. He holds it up and looks after the ball. He’s so good in front of goal with his movement, runs in behind and he’s quick.”

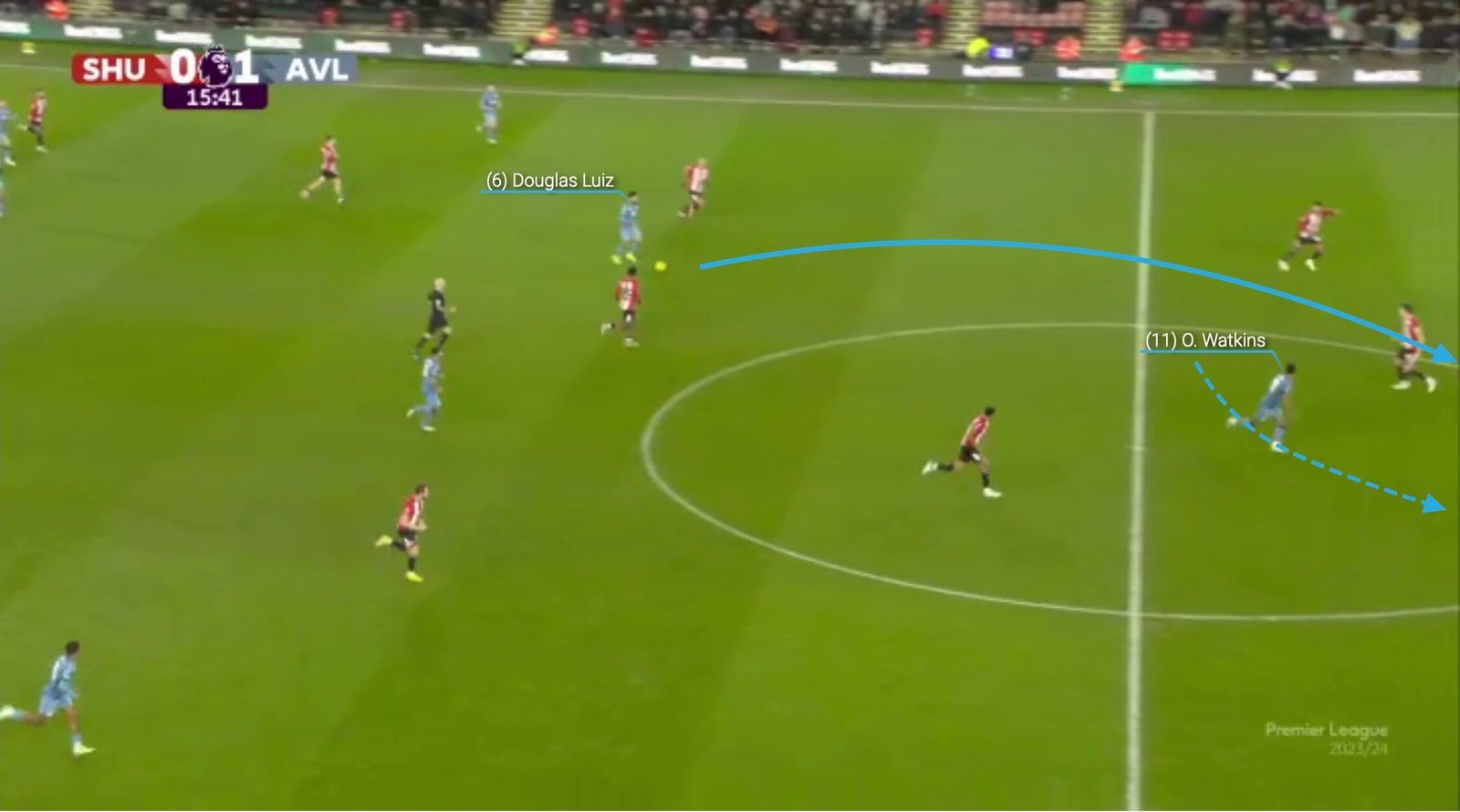

Following Villa’s 5-0 victory at Bramall Lane, Sheffield United manager Chris Wilder identified Watkins’ movement as the “biggest problem”, toying with his side’s back five.

He stretched the defence, making runs into the channels and behind.

Developed over the years, Watkins’ runs aim to be on the blindside of the closest defender, who is unaware of the type and timing of his movement.

Providing the pass is played, Watkins routinely beats the offside trap. In 37 league appearances last season, the flag was raised just 16 times, contributing to Villa being caught offside the second-fewest times of any team.

Butterfield: “Ollie’s evolution at Brentford was massive, giving him confidence about his movements. He found himself far more between the posts as opposed to drifting wide.

“Ollie’s selfish streak began when he stayed between the posts for crosses, instead of being the unselfish striker who runs to the corner flag and ends up getting assists.”

Ollie Watkins: “I have learned a lot in a short space of time. My movement, my mentality, being patient. As a striker, the best example is Erling Haaland. He doesn’t touch the ball for 20 minutes and then scores.”

Pressing

Jordan: “There’s been progress under Unai Emery after Steven Gerrard. That’s no criticism of Gerrard, but if you look at Emery’s team, you can tell when Watkins presses that he’s supported by players around him. Under the previous regime, the press wasn’t as detailed. If you don’t hunt as a group, you’ll run your legs in.”

Hartley: “He’s developed an understanding of what angles to cut off depending on the players behind him, whether he’s going to press high or sit in a mid-block. When I played against him, he would be relentless. Now he’s intelligent in conserving energy.

“He has triggers in knowing when to press as a team, not chasing meaningless balls. The space is never big between Watkins and his midfield, meaning the pitch is condensed and he covers less ground. The difference is Watkins only has to make five-yard runs rather than raking sprints.”

Friis: “In the press, he was good, fast in applying pressure. Brentford had a forward-thinking press and he was one of the keys.”

Hall: “It’s easier when a striker runs in a straight line because you can pass both ways. When they angle their run and show you one way, it’s far more difficult to pick the right pass because they shut off one side of the pitch. Ollie’s good at that.”

Aerial ability

Butterfield: “Ollie’s heading improved and it meant he was a threat on crosses. We moved him into more central areas because he could score headers and receive the ball wide in one-v-ones. At lower levels, sometimes the game passes you out on a wing.”

Jordan: “His heading and how he attacks the ball has got better. He scored a couple of headers and was brave, but he was outmuscled. You’ve got to realise that a lot goes in the box quickly at sixth-tier level — throw-ins, long free kicks and corners. He’s improved so much physically.”

Henderson: “He’s good in the air. As a No 9, he pretty much has everything, he’s a great lad and works especially hard off the field.”

Friis: “With Ollie, it was about finishing. You can say dribbling and holding the ball up was important, but every training session would end with a finish. He was one of our front three and needed to score goals.”

Potential realised

Jordan: “You couldn’t foresee him developing into the physical athlete he is now. His willingness to learn was obvious. My lad is 13 and I say, ‘Watch how Watkins runs without the ball and how he presses’ — he is a throwback. There aren’t too many who lead the line like he does.”

Butterfield: “I’m massively proud. The biggest compliment I can give Ollie is he is one of the most kind, honest and hard-working players I’ve played with. Ollie deserves everything he gets.”

Hartley: “It’s easy for someone to say, ‘Never get too high when you win, never too low when you lose’. But when a young kid is dominating you as he did with me, I was lower than a snake’s belly when I walked off the pitch. I questioned everything. But in hindsight, hands up — he’s in the Premier League and performing week in and week out. I’m not embarrassed what he did to Plymouth that day.”

(Photo: Richard Sellers/Sportsphoto/Allstar via Getty Images)

Read the full article here