“Today, without players who dribble, you can’t do anything,” Pep Guardiola said a couple of years ago, right around the time Manchester City started stockpiling take-on specialists like they were on sale at Costco.

The reason, he explained, was simple: “Attacking a team parked in front of goal without players who dribble and give you superiority out wide is impossible.”

As often happens, Guardiola was out ahead of football’s latest trend. The hottest accessory at this week’s Champions League knockouts isn’t Ivorian leke or an NFL puffer coat — it’s players who can dribble on the wings.

Influenced by Dutch and Spanish positional play, a growing number of teams across Europe are building up slowly in possession and planting a wide attacker on either touchline to stretch the game across the full expanse of the pitch. To prevent counter-attacks, a lot of these teams are holding one or both of their full-backs deeper instead of throwing them forward on the overlap, leaving their wingers isolated against compact defences.

The natural next step is to recruit attackers who specialise in getting around the edges with a solo dribble — not just freestyling through defenders on a fast break, the way wingers always have, but squaring up at the corner of the box after a long possession and deconstructing double-teams from a near-standstill. Most of the Champions League favourites rely on a guy like that, sometimes one on each wing.

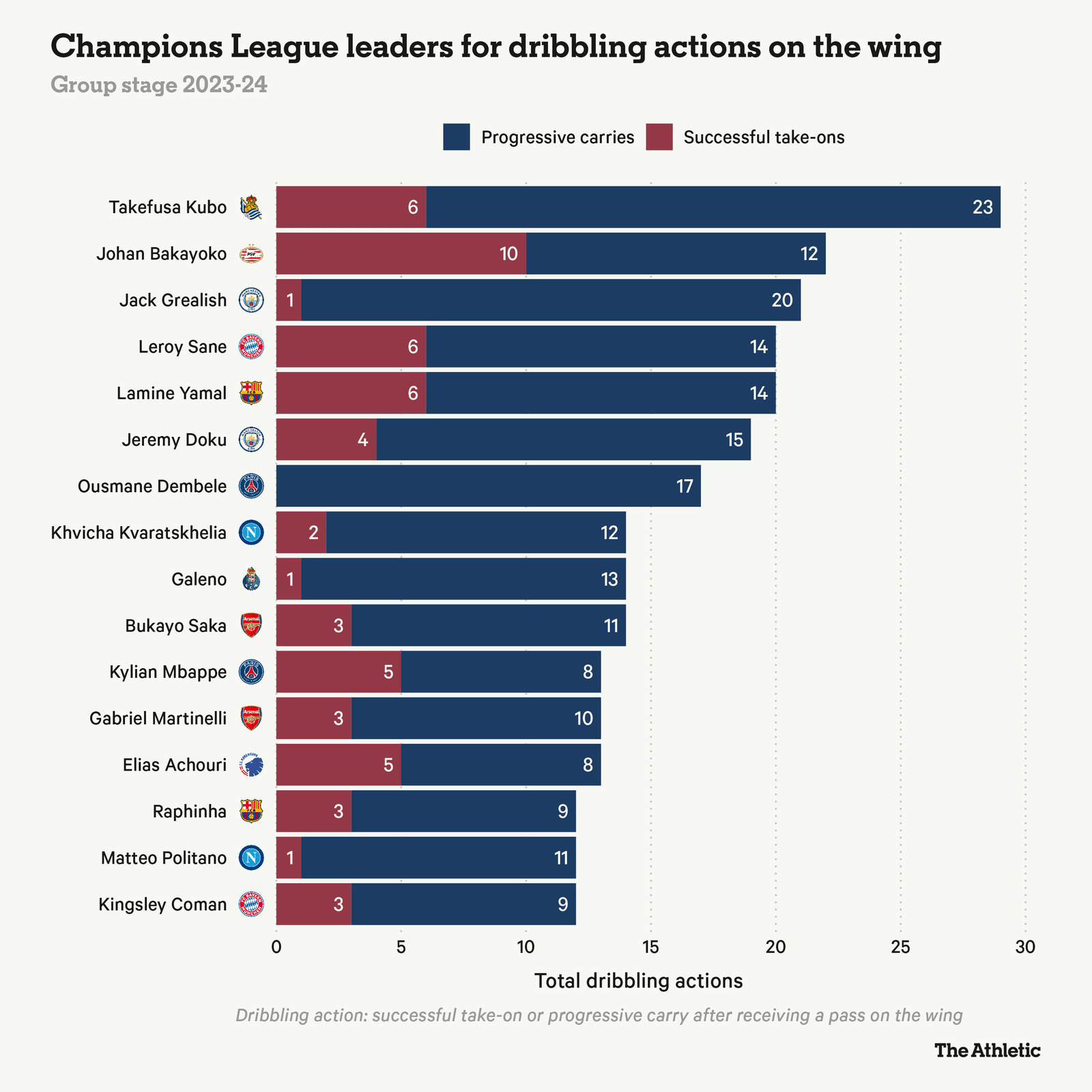

A simple way to measure this tactical shift is a number we’ll call “dribbling actions”. When a player receives a pass on the wings, they’ve got two ways to disorganise the defence with dribbling skill. One is to take on a would-be tackler and get past them. Another is simply to carry the ball far enough toward goal to drag defenders out of position. If you add up these two stats — successful take-ons and progressive carries after receiving on the wing — you get dribbling actions.

The craze for virtuoso wingers is easy to see in the Premier League, where dribbling actions per game are up more than 30 per cent since 2018-19. The Champions League has been a little slower to catch on, but this season’s group stage saw dribbling actions spike to 14 per game, up from around 11 for most of the last five years.

Of the top dozen teams for dribbling actions in the group stage, 10 are through to the knockout rounds. Figuring out how to get around bunkered defences tends to be a rich-people problem. But two of this season’s dark horses, PSV and Real Sociedad, rank sixth and seventh — it won’t just be Man City and Arsenal trying to dribble their way to Wembley for the final.

In the group stage, no one completed more dribbling actions on the wing than La Real’s playmaker Takefusa Kubo and PSV’s human espresso shot Johan Bakayoko.

The interesting part about this leaderboard is its variety of dribbling styles. The job may be the same — get the ball near the sideline and put the defence on skates — but how these guys interpret it is a highly personalised form of artistic expression, like Instagram emojis or questionable tattoos.

Currently, there’s not even much consensus about which direction wingers should go. Other eras were defined by a dominant dribbling style, such as the wide cross-slinging wingers of the Nineties or the cut-and-shoot specialists of the last decade, but right now it’s anyone’s game.

Barcelona’s teen phenom Lamine Yamal loves to cut inside, as does the world’s most famous dribbler, Kylian Mbappe, when he wanders over to the left for Paris Saint-Germain. Dribbling across the face of the defence is difficult and can lead to riskier turnovers, but for players who can pull it off, it’s a more threatening attacking lane than heading toward the corner flag.

The trend right now, though, seems to be toward players who line up on their inverted side, with their dominant foot on the inside, but dribble to the outside. Manchester City’s Jeremy Doku and Arsenal’s Gabriel Martinelli are both right-footed left wingers but not a single one of their 25 combined progressive carries in the group stage went to the inside. (Another high-profile example is Real Madrid’s Vinicius Junior, who missed the list due to injuries.) The difference between this type and a classic natural-footed winger is that instead of hitting wide crosses on their outside foot, they turn back at the goal line for a more controlled final ball.

A lot of top dribblers are skilled at going either way. Kubo gets up the wing for a cross often enough to keep defenders honest, forcing them to drop off and leave a gap for him to cut into the box on his preferred left foot. Napoli’s Khvicha Kvaratskhelia likes to back down his marker with a tiny little feint almost every time his right foot touches the ball, allowing him to dribble straight into the penalty area before deciding which way to go.

Along with tactical considerations, technical comfort with different movements can also affect dribbling style. The graphic below shows which way players tend to turn from different locations, based on the direction of their carries relative to the centre of goal. This includes not just progressive carries but also a lot of smaller turns that can give us a sense of physical tendencies. In zones where a player is equally likely to go either way or tends to dribble straight toward goal, colours are lighter.

Some players would rather turn toward their dominant foot no matter which side they’re playing on, like Bayern Munich’s Kingsley Coman and Leroy Sane. That may limit their flexibility but not their tactical utility, since Thomas Tuchel can swap his wingers based on which way he wants them to dribble in a given situation.

Manchester City’s two right-footed left wingers, Doku and Jack Grealish, have very different styles. For Grealish, who used to play in midfield, the natural tendency is to turn to his right and protect the ball with his body. He gets separation by tapping the ball away from goal with the outside of his right boot and curling a cross to Erling Haaland at the far post.

Doku is an explosive runner whose go-to move is a shimmy and a long touch to burst into space. He doesn’t mind showing the ball to a defender on his right foot, since any attempt at a tackle will only make it easier for him to knock the ball to his left and beat his marker up the wing. He can do the same trick on the other wing, turning to his right, but Guardiola doesn’t like him there. A group-stage game against Young Boys in October was the last time Doku started on the right, pretty much ruling out the possibility that he and Grealish can play together for now.

(Alex Livesey/Getty Images)

Certain players turn different directions at different heights, while for others the choice may be influenced by their distance from the sideline. Barcelona’s Raphinha, for example, will turn onto his preferred left foot when he receives out wide, opening his body to cut inside or circulate possession back into midfield, but when he’s closer to goal he’ll swivel to his right and dribble into the box for a cutback.

But enough about turns and cuts — what about end product? We’ve got some data on that, too. The graphic below shows how often players did certain things per pass received on the wing in group stage. This includes uninterrupted “wing sequences” of consecutive actions by one player, so the numbers add up to more than 100 per cent because it’s possible, for instance, to take on a defender, make a progressive carry and then cross the ball all in one sequence.

Six games isn’t much of a sample to analyse tendencies, and over time players’ percentages would look more similar to each other than they do now, so we should be careful about making too much of this. Still there are some interesting differences in what these attackers try to do with the ball.

Bakayoko in particular stands out as one of just two players on the list who was more likely to take on a defender than to make a progressive carry, as well as the only one whose receptions on the wing were more likely to result in a cross than some other kind of pass. He’s fast enough to knock the ball into space like his Belgian compatriot Doku but his dribbling style is delicate and unpredictable, sort of like a nimbler Kubo.

Instead of slipping up the wing for wide crosses, Bakayoko’s trademark crossing move is to draw attention with a dribble at the corner of the box and then loft a diagonal from the half-space to a runner at the far post. It’s a pass you’re more likely to see from midfielders such as Arsenal’s Martin Odegaard or Bayern’s Joshua Kimmich, but they rely on dribbling wingers to create space and then shovel the ball back to them. Bakayoko is a one-man shop.

If Guardiola is right about which way the game is headed, we should see a lot more of that kind of on-ball innovation in the near future, including from his reigning champions (and dribbling-action leaders) Manchester City. Don’t be surprised if the path to this year’s Champions League trophy starts with a slow, positional build-up and ends with a scintillating dribble from the wing.

(Photos: Getty Images/Design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here