A second life doesn’t come often for football managers.

The increasing hire-and-fire trend has meant that managers and head coaches do not have time to reflect on a failed season, because by that time they could be searching for a new job altogether.

Erik ten Hag came close, but in the end Manchester United extended his contract through to June 2026 by triggering the existing option of an additional 12 months.

A second life for the Dutchman after finishing eighth in the Premier League, United’s worst final position since the competition began in the early 1990s and with a negative goal difference across the 38 games, and exiting the Champions League at the group stage with one win and four defeats in the six matches, but winning the FA Cup to deny neighbours Manchester City the double.

Despite their convincing 2-1 victory over the four-in-a-row league champions at Wembley, performances throughout last season were depressing. Injuries played a major role as United seemingly struck up new back-four combinations every week, but there were structural problems and subpar individual performances as well.

After a successful debut season in English football, Ten Hag now has the opportunity to redeem himself and build on the positives of that 2022-23 campaign while fixing the problems of year two. In a turbulent season that featured off-field problems, new ownership buying a stake in the club, and numerous injuries, the performances throughout 2023-24 were much worse than the results.

The vote of confidence in Ten Hag needs to be supported by incoming players as the club correctly targeted centre-back, central midfield and forward as their priority positions in the summer window, with Joshua Zirkzee arriving from Bologna. Yet, the manager needs to also reflect on last season’s failings. After their opening pre-season game on Monday, a 1-0 defeat away to Rosenborg, Ten Hag said their performance had been “below the standard”.

It’s tough to summarise United’s problems because, rather than stumbling in a certain phase of play, there were difficulties all across the board.

The most striking issue was the side’s inability to limit opponents’ chances. United were porous without a functional high press or a solid organisation out of possession, which allowed teams to play through them and create dangerous opportunities. It also meant Ten Hag’s team had to drop deeper and defend their penalty area, which suited some United players but allowed opposing sides more shots and greater control.

While Monday’s game was only a friendly, Rosenborg had 22 shots to United’s five, extending a streak which has seen Ten Hag’s side concede a double-digit number of attempts on goal every time they have taken to the pitch since the FA Cup third-round win against Wigan Athletic of League One, the third tier of English football, in January.

The underlying numbers last season suggested they were struggling to contain their opponents, with United’s 1.7 non-penalty expected goals (xG) conceded per game the fourth-worst in the Premier League. As shown by The Athletic’s playstyle wheel below, which outlines how a team look to play compared with Europe’s top seven domestic leagues, their approach in and out of possession seemed rather confused.

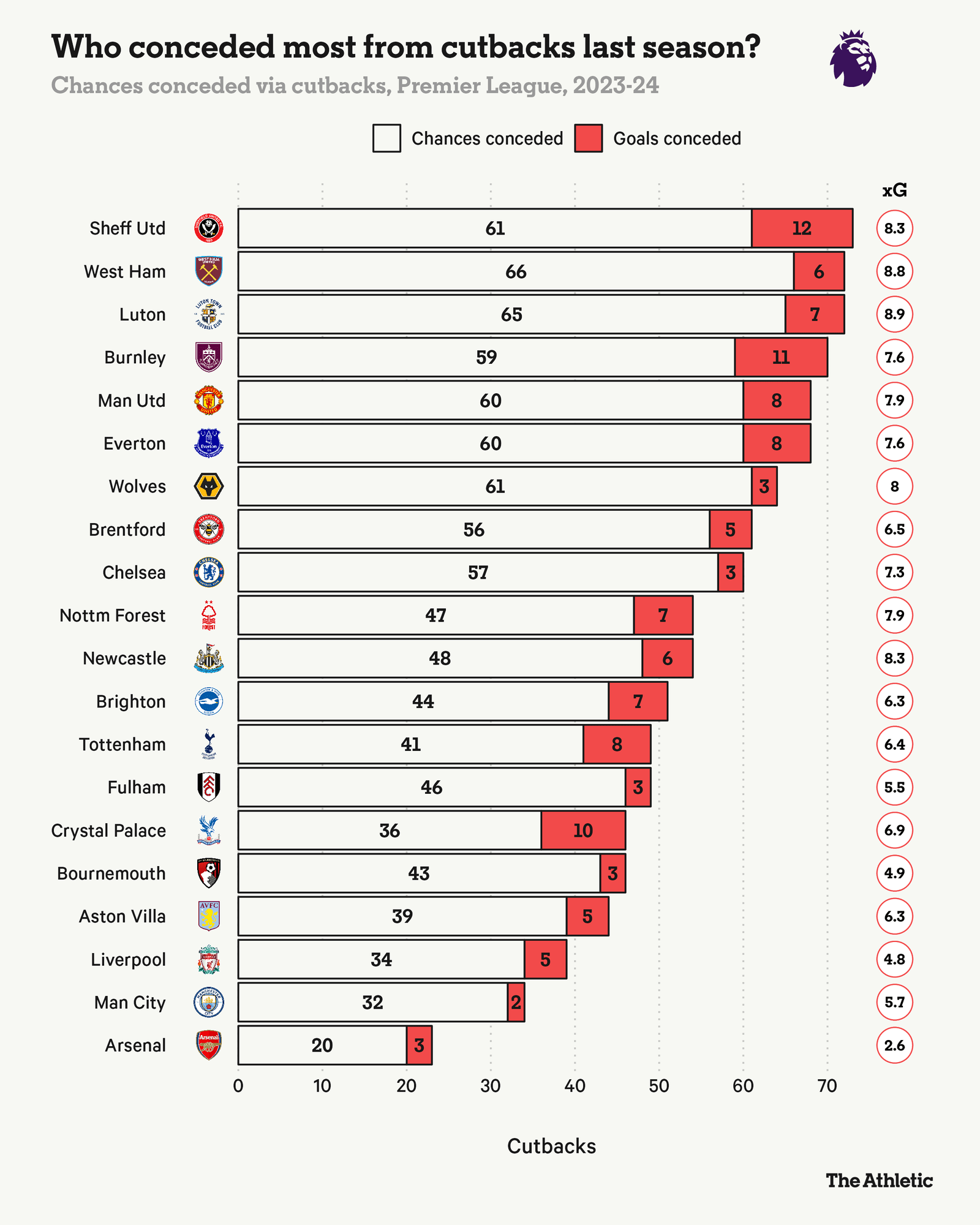

One of the areas where United’s defence suffered last season was trying to defend against cutbacks. The lack of protection of the space between the dropping defence and their midfield colleagues was constantly exploited by opponents.

Only four Premier League teams conceded more chances from cutbacks — three of those, Sheffield United, Luton Town and Burnley, were relegated while West Ham United allowed six goals from cutbacks compared to United’s eight.

Ten Hag needs to find a solution. The main issue last season was the back four’s inclination to drop, protecting the space between them and goalkeeper Andre Onana, with the midfielders not returning in time to take care of the space in front of their defensive team-mates.

In this example, against Sheffield United in April, Gustavo Hamer is playing the ball wide to Ben Osborn, with Ten Hag’s back four inside the penalty area, Christian Eriksen focusing on the ball, and fellow midfielders Bruno Fernandes and Kobbie Mainoo recovering.

Aaron Wan-Bissaka is defending the ball, so has to drop deeper, and Diogo Dalot is tracking Cameron Archer’s near-post movement, but Harry Maguire and Casemiro move back as well, with Fernandes and Mainoo far away from the action. This creates space in the cutback zone, which allows Osborn to find Ben Brereton Diaz…

… who puts the ball into Onana’s net.

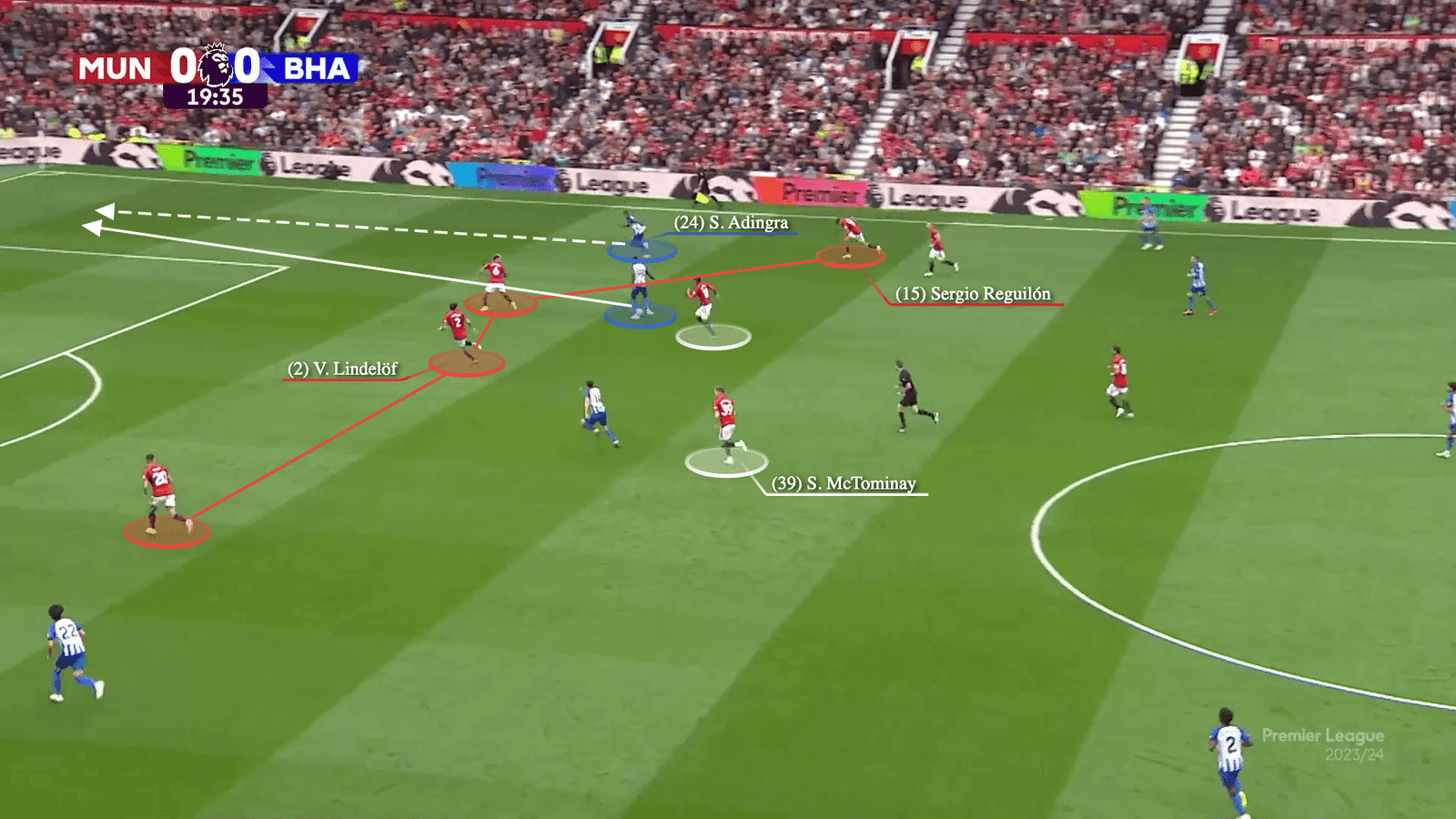

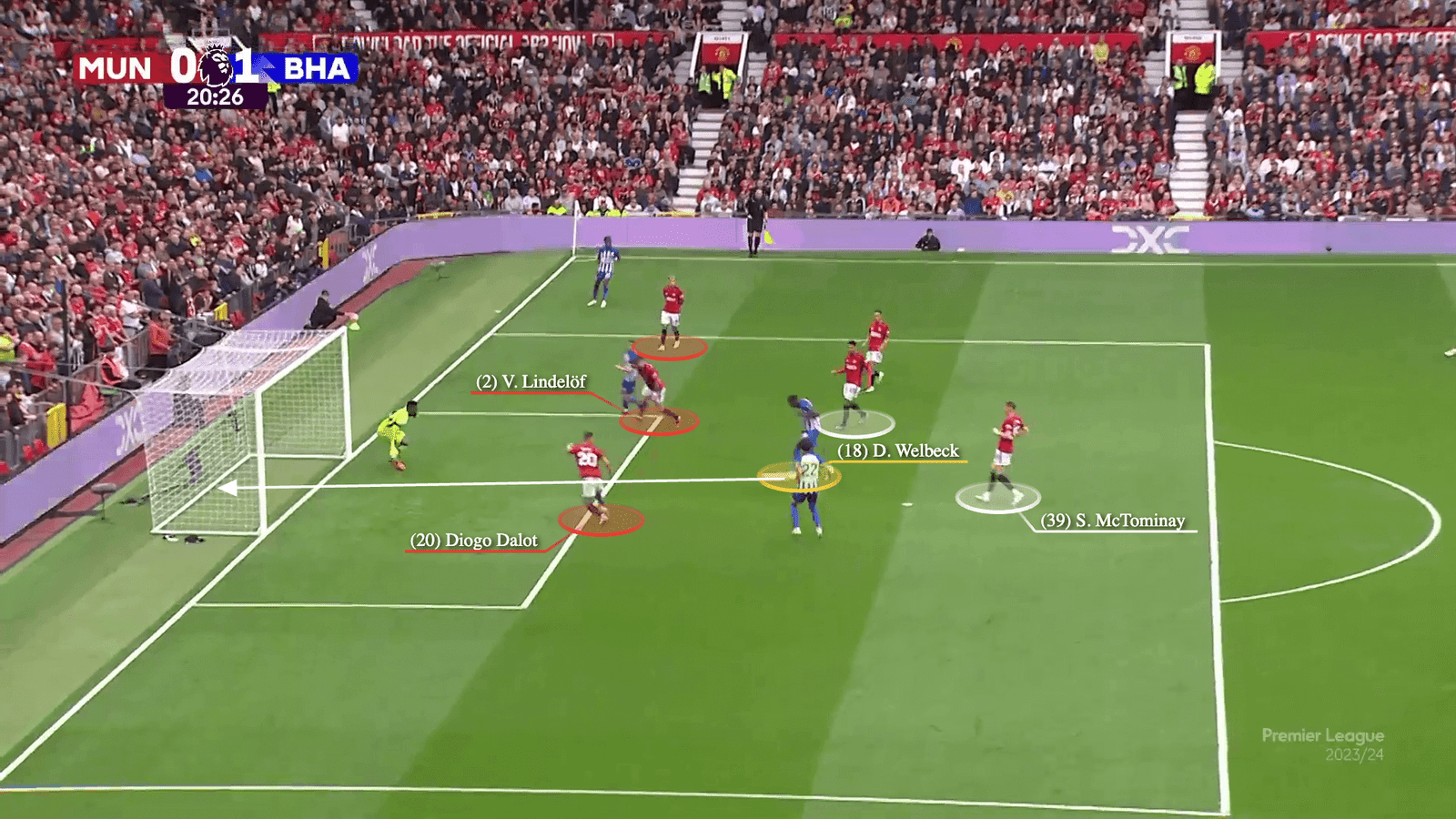

In another example, against Brighton & Hove Albion early last season, United’s back line didn’t have a choice and the midfielders should have recovered in time to defend the cutback zone.

Here, Brighton play through United’s block to find Simon Adingra down the right wing, with Casemiro and Scott McTominay moving back to assist the defensive line.

Sergio Reguilon is caught out by Brighton’s combinations and Lisandro Martinez has to move out to cover, leaving Victor Lindelof and Dalot to defend the central space in the penalty area. However, United’s right-back and centre-back are occupied by Kaoru Mitoma and Adam Lallana, which means they can’t keep their positions to defend the cutback zone.

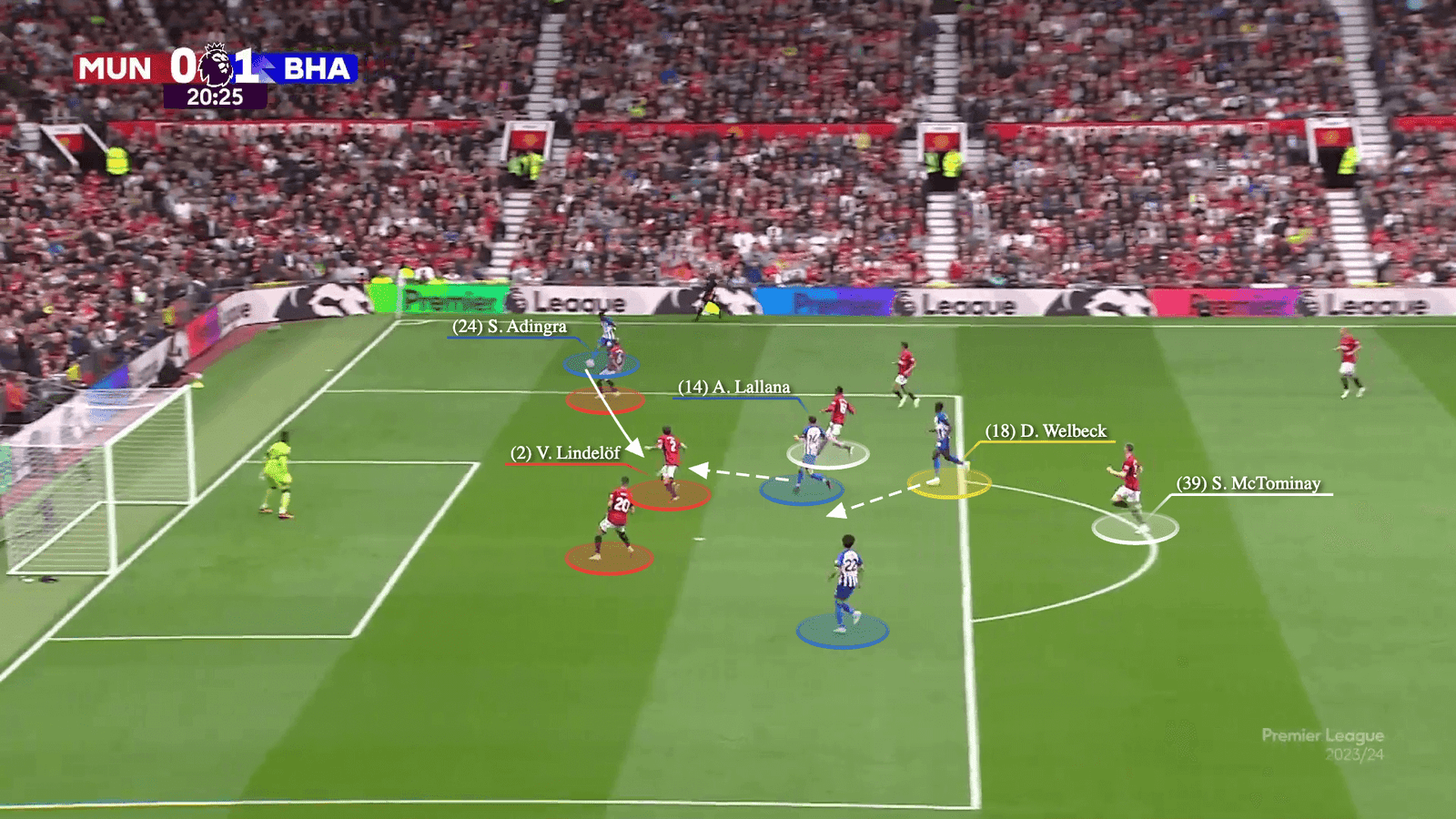

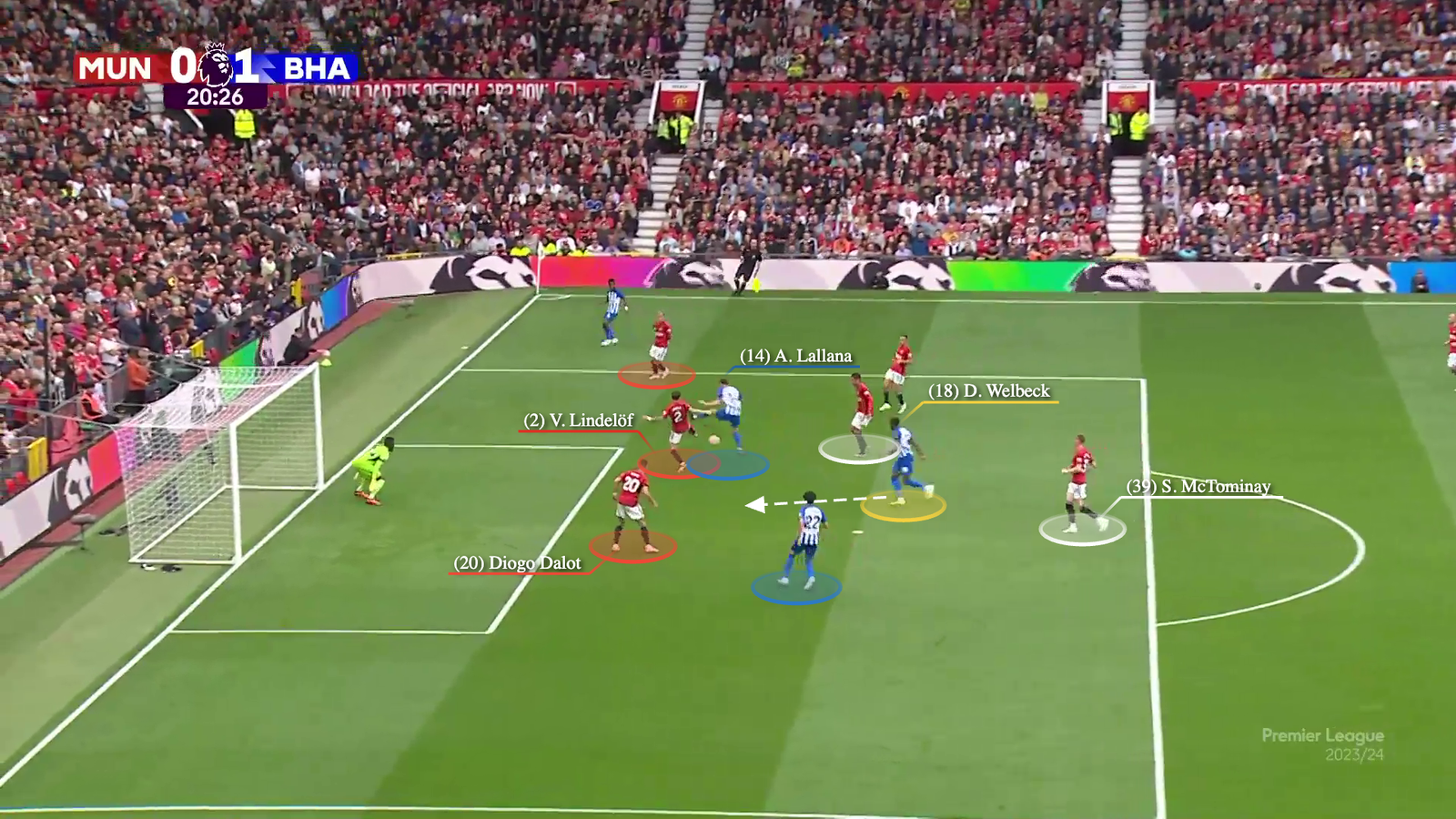

Accordingly, Danny Welbeck attacks that area, with Casemiro and McTominay not dropping in time. Lallana dummies Adingra’s cross, which finds its way to Welbeck…

… who scores to give Brighton the lead.

Another problem concerned their defensive transitions.

When Ten Hag’s team lost the ball, there were acres of space for the opponents to attack as United’s midfielders and defenders scrambled to defend the counter-attack.

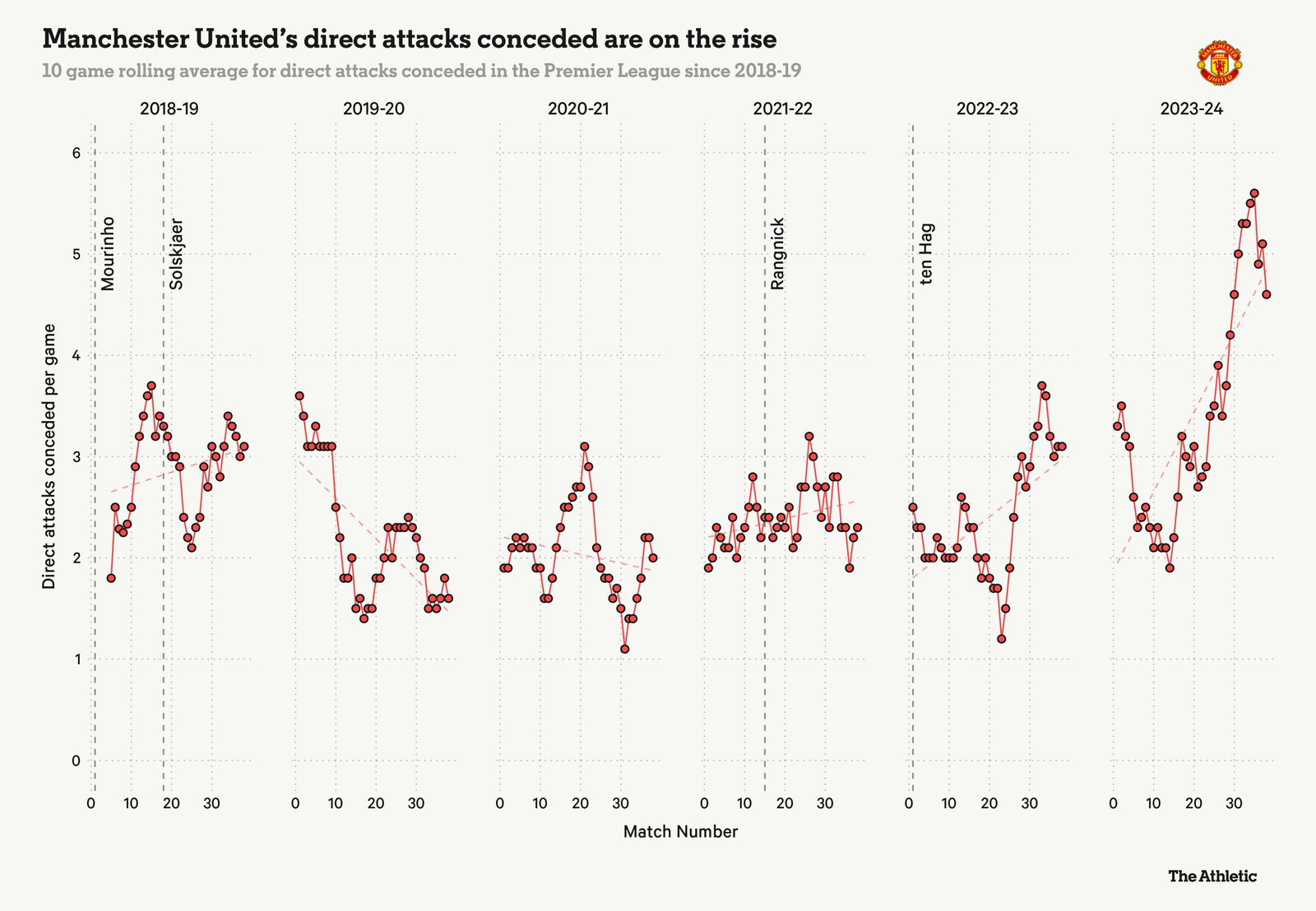

That is visible in the number of ‘direct attacks’ United conceded. Those are defined as possessions which start in a team’s own half and result in either a shot or a touch inside the opposition penalty area within 15 seconds — in other words, a counter-attack.

United’s rate of 3.4 direct attacks conceded per 90 minutes in the 2023-24 Premier League was their worst of the past six seasons, and their rolling 10-game average below highlights the sharp spike compared with previous years.

The consensus is that United’s transitional nature under Ten Hag and the profiles of the attacking players will lead to this. “We really looked into the history of Manchester United and we looked also into the qualities of our players,” said Ten Hag last summer. “And then you can say, so what do we want to be? That is, we want to be the best transition team in the world. We want to surprise.”

To be the best transition team in the world, there’s a balance to strike between attacking the opponents as fast as possible when you have the ball and knowing when you need to control the game. Last season, United didn’t find that balance.

“We have to recognise where we have to keep the ball, to keep the ball longer,” said Ten Hag last March. “Otherwise we are coming into a tennis match and when we want to play tennis, we go to Wimbledon.”

The rushed nature of United’s attacks in settled possession regardless of the game state — losing, drawing or winning — or the amount of time remaining in the match resulted in wrong decisions and actions.

This lack of a controlled approach also affected the spacing between the players, resulting in a poor rest-defence structure, which meant that when Ten Hag’s side gave the ball away, they were much more open on the defensive transition — taking more passes or waiting for the right moment to break down their opponents would allow the United defenders to be in better positions to counter-press in case possession is lost.

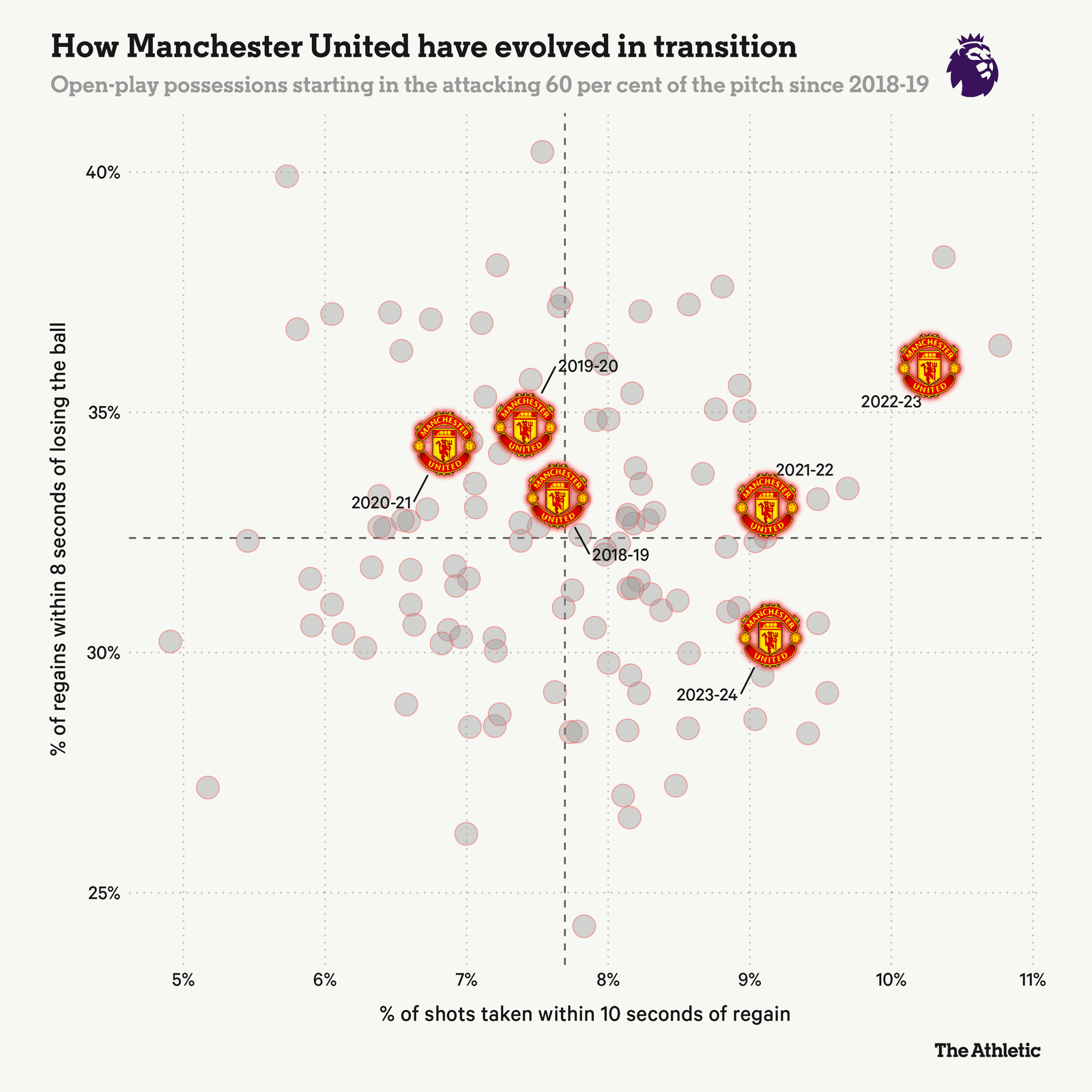

Compared to Ten Hag’s first year as their manager, United’s counter-pressing took a hit in 2023-24.

Last season, 30 per cent of United’s possession regains in the attacking 60 per cent of the pitch came within eight seconds of losing the ball — six per cent fewer than in the previous campaign.

When Ten Hag was asked by The Athletic’s Carl Anka what he was looking to improve in his team’s defensive transitions, the answer was “better rest defence”.

“Are the decisions on the ball better? Go for goal, be direct for making a goal, or keeping the ball — otherwise, you stretch the pitch,” said Ten Hag last April. “And then it’s about once we lose the ball, looking for the reactions and the players’ behaviour. What positions do they take?”

Moving away from being a transitional team doesn’t make sense considering the profiles of United’s forwards, but there’s a balance to be found. A gung-ho approach regardless of the situation was what left United’s defenders and midfielders defending vast spaces on the transitions.

Listening to Ten Hag’s press conferences throughout last season gave the impression he wanted to achieve that balance, but the outcome on the pitch didn’t reflect that ambition.

“I came here with my philosophy based on possession, but also to combine it with the DNA of Manchester United and combine it with the players and the competences and with the characters of the players,” Ten Hag said in November. “This season, the philosophy is not different and I would emphasise more on going direct.

“But with the explanation of going direct, they (the media) thought I wanted to go for long balls. No, I don’t.

“I didn’t buy Andre Onana (last summer) to go for long balls. We want to play from the back as we did, and we tried every game. What I meant with ‘directness’ is, we want to press. We want to press from different blocks, and then go direct because we have the players who are very good in it (transitions).”

Besides their attacking threat in those situations, United’s ambition to control games means opponents will drop into a low block, especially those teams who don’t have the same level of individual quality as them — being behind is another situation where United could find themselves searching for ways to score against a defensive block camping near their own penalty box.

When that happened, United failed to constantly find solutions which didn’t involve a moment of brilliance from one of their attackers. The most structured teams still need individual quality to break down a defence, but against deep defences, it looked like it was United’s only option in Ten Hag’s first two seasons. Rather than complementing a cohesive attacking structure, the individual talent was regularly burdened with the task of finding answers.

The unavailability of some attacking players — whether through injuries or off-field matters — and underperformance of others didn’t help. “So often, we have to change the team,” Ten Hag said in December. “You don’t get the routines. Football is about solid performance and consistency — and we have to make a step there — but when we have more players available in the key positions, we will get more consistency.” But the lack of effective solutions in the attacking third had been a concern in 2022-23, too.

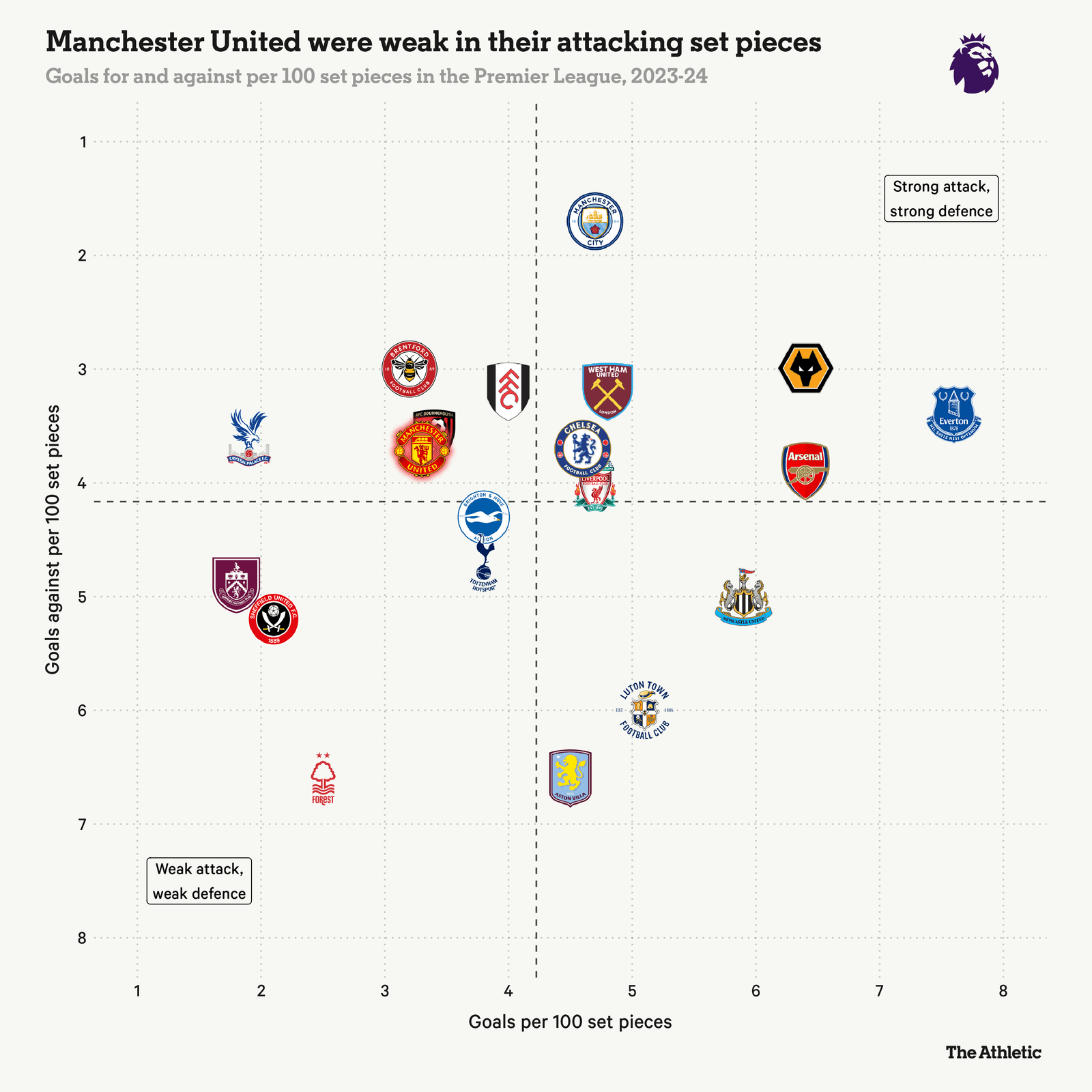

Another part of United’s game in need of improvement is their attacking set pieces.

Looking at the goals per 100 set pieces in the Premier League last season — which creates a fair and level playing field across all 20 teams, as one might have more set-piece opportunities than another — United’s rate of 3.3 was sixth-worst in the league. On the other hand, their defensive set pieces have been slightly above average across the league.

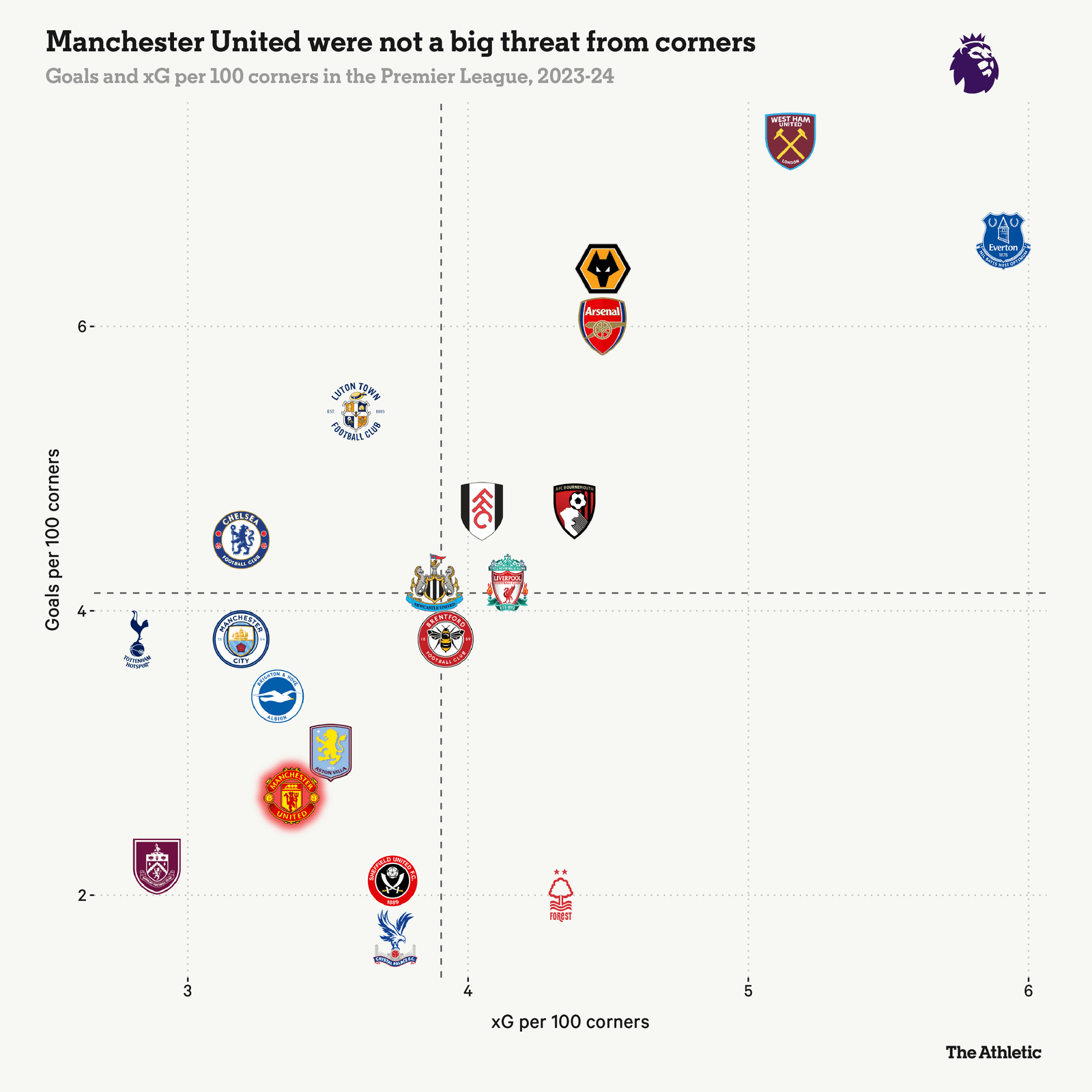

Specifically, United’s inefficiency from offensive corner kicks hindered their set pieces. Considering the number of corners United accumulate each season, they are a valuable tool Ten Hag isn’t using to its fullest strength — especially since his team aren’t the most effective when breaking down low blocks.

Last season, United’s goals-per-100-corners rate (2.7) was fifth-worst in the Premier League, and it wasn’t because they were creating high-quality chances and missing them — only five teams had a worse xG-per-100-corners record than their 3.4.

It’s possible to pick out problems in most phases of United’s game — whether that’s a dysfunctional press, poor organisation out of possession, inability to break down deep defences, unbalanced style of play, lack of clarity in the build-up, or toothless set pieces — but last season is over, with all of its injuries, Ten Hag’s tactical issues, underperforming individuals and lack of certain profiles.

The circumstances have allowed the United manager a fresh start, and he will be hoping to build on the successes of his first season in Manchester, correct the mistakes of the second and target the players in the transfer market who will raise the level of the squad as we go into year three.

“We are highly ambitious, so we have to raise our standards day by day, and improve every day,” said Ten Hag, looking ahead to the coming season. “Every time, we have to live with the line in our head – ‘Good is not good enough’. We have to do better.”

There’s a lot to fix if Ten Hag wants his second life at United to last longer than the first.

(Top photo: Justin Tallis/AFP via Getty Images)

Read the full article here