Ahmed Refaat celebrated his 31st birthday on June 20 in the Cairo television studio of the MBC Egypt channel.

The Egypt international footballer, one of the country’s most talented players and a friend of Liverpool forward Mohamed Salah, was there to explain the “miracle” of his recovery after collapsing on the pitch four months earlier, having suffered a cardiac arrest. His heart had stopped beating for nearly two hours before doctors restarted it and placed him into an induced coma. He subsequently underwent two heart operations to save his life.

You can see the footage of Refaat’s interview on YouTube. He looks tired, and his words come haltingly. Only two days before the interview, he admitted he was still feeling so ill, “that I said my prayers. I thought that I was going to die.”

During breaks in the interview, Refaat would fiddle with his phone, texting his agent Nader Shawky, who was just behind the camera, telling him: “I keep forgetting, I keep forgetting. Remind me. Do you remember?”

Yet there was something else troubling Refaat, a matter only a select few people knew about, and he was adamant it had contributed greatly towards his health problems. “What happened to me and what I had to go through isn’t normal for a football player, or a normal person for that matter,” he murmured.

Refaat never revealed what was at the root of his disquiet. Sixteen days later, Refaat’s death was announced by his Egyptian club, Modern Sport, following a sharp deterioration in his condition.

“God took him after an arduous journey of struggle following the health crisis that occurred to him,” a statement read.

Refaat died leaving a trail of unanswered questions that nevertheless shine a light on the actions of a variety of influential people and institutions in the country.

These stretch from Shawky, described as “one of the most powerful agents in African football”, to the president of the Egyptian Premier League, Ahmed Diab, to the Egyptian government, which stands accused of placing undue stress on Refaat during a two-year attempt to enrol him in the army. It is this which many believe Refaat was referring to in his cryptic television interview.

Since his passing on July 6, The Athletic has spoken to a number of people in Egypt familiar with the player about the issues affecting him, and the circumstances surrounding his illness, his attempted recovery — which Salah tried to help with by providing advice about the best doctors to use in England — and tragic death just as he was planning to travel abroad.

This is his story.

The moment the clock began ticking on Ahmed Refaat’s life was in the 88th minute of a match between Cairo’s Modern Future FC (renamed on July 2 as Modern Sport) and Al Ittihad from Alexandria on March 11.

Refaat had been introduced as a second-half substitute but, as the game drew to its conclusion, his legs suddenly gave way. He did not wake up until a week later in a hospital, attached to all sorts of machinery.

Refaat said in his MBC Egypt interview that he remembered nothing about that day, but the effects of it were profound. He had been placed on a cocktail of medications, to be taken five or six times a day and through the night, which made him perpetually drowsy. His mother — Refaat’s father had died when he was 13 — became his effective carer, working around the clock.

Refaat was not a global superstar, on the level of Salah, but he was talented — good enough to be handed trials at European clubs such as Switzerland’s Basel (his time at the club coincided with Salah’s) and Sevilla in Spain, and play for Zamelek, one of Egypt’s two biggest clubs.

He helped Egypt Under-20s win the Africa Cup of Nations in 2013 and won seven senior caps by his country, scoring twice, having been handed his debut in a 3-0 friendly victory over Uganda by Bob Bradley, the former USMNT head coach, who considered him one of the country’s four most promising young players.

“What has happened to him is just terribly sad,” Bradley tells The Athletic from Norway, where he is in his second spell managing Stabaek. “Sure, 1992 was a good year for Egyptian football because Mo Salah was born. But I was pretty excited about the intake from 1993 as well. This involved Ahmed (Refaat), as well as Ramy Rabia, Kahraba and Saleh Gomaa.”

Ahmed Refaat was judged as one of the most talented players of his generation in Egypt (Karim Sahib/AFP via Getty Images)

“You could see how excited all of the young guys were. For Ahmed, being called up to play for Egypt meant so much to him. He was optimistic and proud. That’s how I remember him. Everyone liked him.

“We called Ahmed up even before he’d played for his (Cairo) club ENPPI, so I guess that shows you how much we liked him. He had a good energy. He played simply and sensibly. The most important thing was, he listened. He wanted to improve.”

It was a view shared by his teammates. “Ahmed was incredibly talented,” Adam El-Abd, the former Brighton and Hove Albion defender who played alongside Refaat for Egypt, tells The Athletic. “He was very quick and had good feet. He had an eye for goal. I would never have imagined him suffering from any health problems because he was so fit.”

Refaat himself had not accepted that he would never play again following his collapse in March. He had had a pacemaker fitted and hoped to emulate Denmark’s Christian Eriksen, who had returned to the elite level after his own cardiac arrest during a European Championship game in 2021. Refaat was also engaged, and looking forward to getting married.

Shawky would later confirm live on television that just a day before his client’s death he was planning to travel to England and Italy for medical treatment.

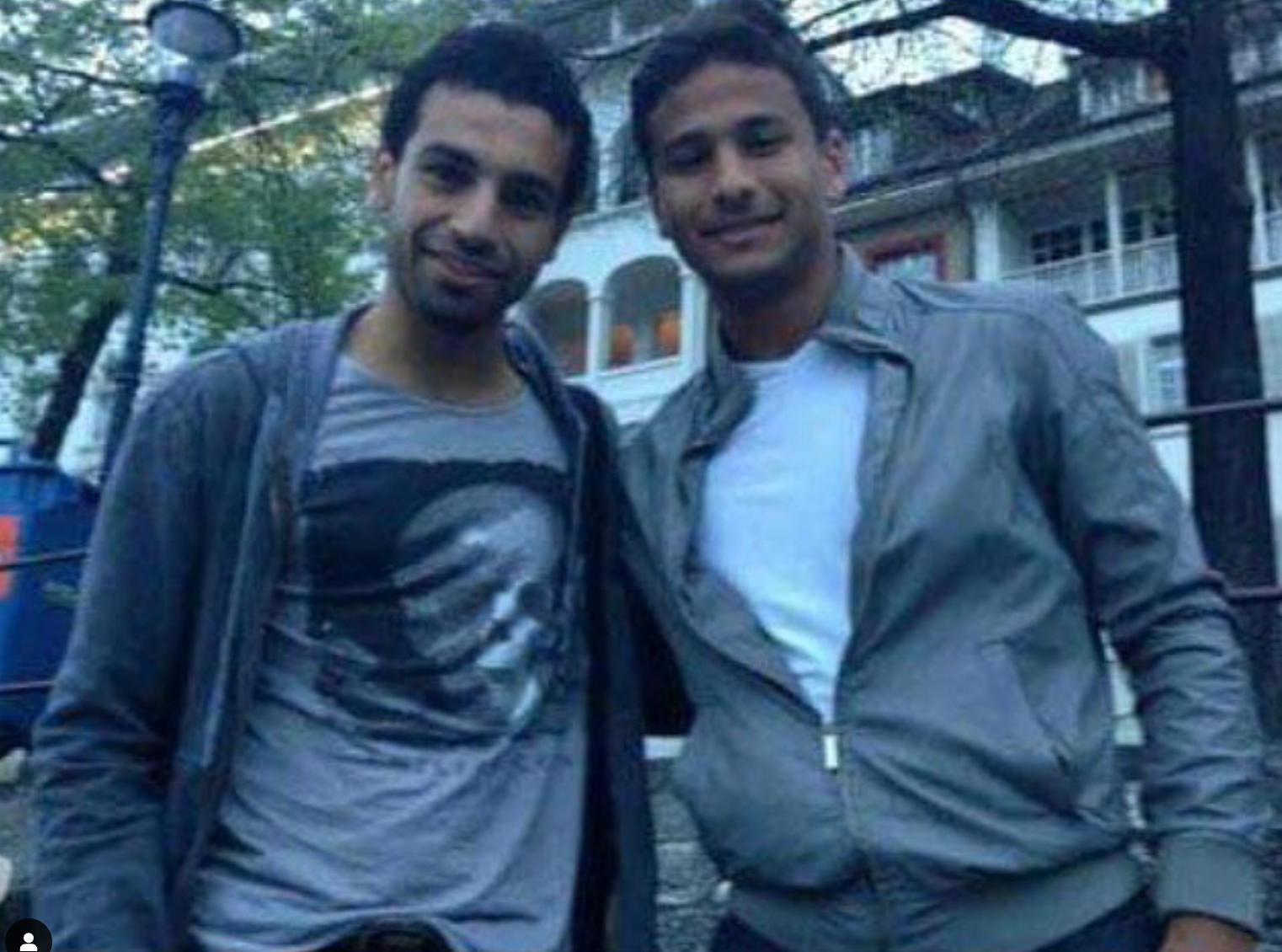

His passing shocked Egyptian football, with Salah posting a picture of Refaat on X with the message, “May God give patience to his family and all his loved ones.”

Mo Salah and Ahmed Refaat together in Switzerland in 2013 (Instagram/@refaatahmed10)

Following his collapse, Salah tried to support Refaat by playing an advisory role about which doctors to use as he plotted his recovery. Tragically, Refaat would never get to see them.

On July 7, a day after Refaat’s death, Shawky was sitting in the same Cairo television studio that had hosted his late client.

He was listening to Refaat’s brother, Mohammad, who was claiming via a telephone link that his sibling had suffered “psychological damage” and he suggested anyone wanting to know more should “ask Ahmed Diab.”

He did not have to wait long for an answer. Diab, who prior to taking up his role with the Egyptian Premier League had been the owner of Modern Sport, duly rang into the show to defend himself.

The call prompted what might euphemistically be described as a robust exchange of views. Shawky accused Diab of failing on his promise to get Refaat the correct travel permits when he sanctioned a lucrative deal in late 2022 to loan him to Al Wahda, a club based in the United Arab Emirates.

For Refaat, this had grave consequences. Soon after arriving in the UAE, he received phone calls from Egyptian government officials, telling him he was now considered a fugitive as he had not been given the requisite permission to travel amid an ongoing row relating to his non-enrolment in the army. They demanded he return home immediately.

Though Refaat had a promising start to his career in the UAE, the strain of his situation quickly started to show. Inside two and a half months, his contract was terminated, meaning his residency in the country was also over.

“He felt injustice, unfairness; he felt he was played,” Shawky said. “Refaat was a proud person.”

Upon his return to Egypt, Refaat was arrested and imprisoned for two months at a military barracks, where he was permitted to train with Tala’ea El Gaish, the Egyptian club with deep connections to the army.

It was Shawky’s view that Diab did not try to help Refaat’s defence. Diab, however, was adamant that he was not to blame, saying on MBC Egypt that he had secured the permits for Refaat to travel firstly to Liberia, as part of the Future FC squad for a game in the African Confederations Cup, and then onto the UAE. Diab also said that after selling the club, he held several face-to-face discussions with senior military personnel about the player’s precarious position.

Diab had stopped communicating with Shawky by the time the player collapsed in Alexandria, but he insisted that he subsequently checked on his welfare via a series of phone calls.

It was at this point that another party entered the studio conversation. Mohamed El-Shazly, a spokesman for the Ministry of Youth and Sports, which originally issued Refaat with the permits to go to the UAE, denied that his department had been instrumental in ordering the player to return to Egypt. He said that the ministry’s permit was only the “first step” in the process. It was, he said, ultimately the army’s decision how long any person from the country was able to remain abroad for.

In Refaat’s case, the ministry’s decision covered just a three-month “trial”, a period which clashed with the terms of his contract in the UAE. He was due to stay at least a year with Al Wahda, who then had an option to buy him.

El-Shazly insisted it was the responsibility of any footballer moving to another country, along with the administration of the club he was leaving behind, to ensure this process was followed. With that, Diab’s involvement in the call ended. His social media accounts have been inactive ever since.

The Athletic approached Diab and Shawky. Shawky declined to expand on what he had told MBC Egypt, while Diab did not respond to requests for comment.

Barely any of the studio discussions focused on the pressure exerted by the military, perhaps understandably given the control it has had over Egypt since 2013 when army general Abdel Fattah el-Sisi led a coup d’etat to unseat the democratically elected president Mohamed Morsi.

Even before Sisi, it was mandatory for Egyptian men with brothers to apply for military service at the age of 18. Exemptions are made for students entering higher education until they are 28, and it has been common for footballers to register at universities because of this loophole. If still active as “students” 10 years later, they are then usually obliged to join the army before returning to finish their education at a later date.

Abdel Fattah al-Sisi seized power in Egypt after a military coup (Charles Platiau/POOL/AFP via Getty Images)

The Athletic has been able to establish that Refaat was 28 when the army called on him in September 2021 via correspondence from Egypt’s military sports authority sent to his club at the time, Al Masry. They demanded that he start military service, during which time he would move to Tala’ea El Gaish, a Cairo-based club set up in 1997 to effectively serve as the army’s unofficial club.

Al Masry circumvented this by transferring two other players to El Gaish, a practice that has long been common in Egyptian football. Though non-state clubs like Al Masry have been able to keep hold of footballers like Refaat, they are still requested to register at a military base regularly, sometimes as often as once a week.

Refaat did move on from Al Masry five weeks after the club received its request from the military, but rather than join El Gaish, he moved to Future FC, the club owned by Diab. Through its owners at the time, they had unofficial links to the state’s ruling party, originally named after the Nation Future political party, created in 2013 to support the Sisi regime. Those links are no longer there under the current ownership.

Refaat’s form was good enough to be recognised by the Egypt national team and at the Arab Championship in December 2021, he was the top scorer for a team that finished the competition in fourth place.

Ahmed Refaat celebrates scoring against Jordan at the Arab Cup in 2021 (Karim Jaafar/AFP via Getty Images)

On October 8, 2022, Al Wahda announced that Refaat had signed for the club on a one-year loan deal. It was a timely as well as a lucrative deal for Refaat, who was soon to turn 30: a month earlier, he had been suspended by Future after a fight with the team’s goalkeeper during an African Confederations Cup game in Uganda. Shawky later claimed the incident was out of character.

Refaat was requested to travel with the squad to Liberia via Ghana, but once he had arrived there, he was told that he did not need to complete the onward journey because an offer from Al Wahda had been accepted. Instead, he would travel to the UAE in a private jet.

Refaat’s lawyer has suggested that flying to the UAE from Ghana rather than Liberia became a problem because there was no mention in the player’s documents about a transit country. In the eyes of the Egyptian army, this meant he would be arriving in the Middle East illegally.

Instead, he flew to the UAE from a country that he was not permitted to travel from, with documents that did not cover the length of his loan contract. Refaat was subsequently bombarded with requests by the Egyptian authorities to return home.

Diab allegedly reassured him that he would try to resolve the problem but on December 25, just 10 weeks after landing in the UAE, his contract was cancelled, though nobody was aware of this development in Egypt until February 1, when it was announced he was returning to his former club following the end of his loan.

Photographs were later posted on Refaat’s social media of him training alone at a facility associated with El Gaish. Yet on March 8, 2023, he returned to the Future team as a substitute against Morocco’s FUS Rabat in the Confederations Cup, despite not being registered to play for them (Future were later docked the points from their 2-0 victory).

Refaat did not appear for a game against El Gaish on April 19, despite his agent claiming he was fit; indeed, he did not play at all again until June 6. This led to suggestions that the conditions of his imprisonment dictated he could not play against any Egyptian club with links to the military.

Between January 2023 and when he collapsed in March 2024, Refaat played just 11 games. Following his imprisonment, he remained under the custody of the armed forces for another six months, mainly training alone.

Refaat’s case with the military ended just two months before his death, but only after his club was sold to Walid Dabas, a businessman who owns a large group of universities and schools. An agreement between the club and the Ministry of Defence meant that the player officially had still not served his conscription.

It will never be proved quite how much the pressure experienced by Refaat during these wrangles with Egypt’s government contributed to his death, although doctors have since publicly suggested that stress was a factor in his heart problems.

What is beyond dispute, however, is that the influence exerted by the authorities — particularly in the military — on footballers can be extreme.

Salah, by far his country’s most famous player, was only spared military service in 2014 after an intervention from the Egyptian prime minister. When he signed for Chelsea that year, he was only permitted to live in London on the basis of his participation in an “educational” programme.

When Egypt’s minister of higher education rescinded his registration, it was reported that if he returned home he would not be able to leave the country again until the completion of a period of military service, ranging from 12 months to three years.

Salah did not speak about the decision but Ahmed Hassan, a director with the Egyptian national team, suggested the player was in “shock.”

Mohamed Salah felt pressure from the Egyptian authorities around the time of his move to Chelsea (Clive Mason/Getty Images)

Hassan said: “He told me that he is trying to represent Egypt in the best way possible. Is this the best response from the country?”

Ultimately, the national team manager Shawky Gharib was able to argue that the ruling was “threatening” the future of Egyptian football.

Like Refaat, Mohamed Zidan was also 28 when, in 2010, he was detained in Egypt a decade after leaving Port Said for a career in Europe where he played in Denmark and Germany. Zidan, then on the books at Borussia Dortmund, was only allowed to leave Egypt because he was suffering from a knee injury, which meant he was unable to pass his medical for the armed forces.

Zidan retired in 2013 but he surprisingly returned to football nearly two years later in Egypt with El Entag El Harby, a club with links to the military and one that has benefited from being able to recruit players serving in the army.

Zidan did not respond to a question from The Athletic about whether his arrival at El Entag El Harby was related to military service.

Mohamed Zidan (right) had issues with returning to Egypt after his move to Borussia Dortmund (Patrik Stollarz/AFP via Getty Images)

While joining one of Egypt’s military clubs means players avoid long periods of camp time, some — speaking to The Athletic on the condition of anonymity to protect their safety — have subsequently experienced a sense of being a virtual prisoner.

One player says he was threatened with active military service on the Sinai Peninsula near Egypt’s border with Israel if he did not renew his contract at the military club, a decision which would have ended his career altogether.

It is also striking how many of these stories — including Refaat’s — involve Tala’ea El Gaish, the army club. In 2004, they signed Abdel Sattar Sabry, a former Benfica midfielder who had been arrested at Cairo International Airport and questioned by immigration officials about the validity of his European Union passport. Officials had also accused him of evading military service.

Though Sabry was in the process of finalising a move to Al Ahly, the biggest club in Egypt, he surprisingly signed for El Gaish, a middle-ranking team, where he remained for the last five years of his career.

The Athletic approached Sabry for comment but did not receive a response.

More recently, in 2021, Ceramica Cleopatra, a club promoted to the Egyptian Premier League for the first time in its history, announced the signing of midfielder Mido Gaber from Misr Lel Makkasa but seven days later, he went missing from the team’s Cairo hotel during a training camp.

“Two people had asked to take photos with the player, then he left the hotel with them. Since then, Gaber’s phone has been switched off, but all of his belongings are still in the hotel,” said the club’s director of football, Moataz El Batawy. “We don’t know if he was kidnapped so we filed a police report.”

The next public sighting of Gaber was in an El Gaish shirt, where he spent the season “on loan”. He subsequently did move to Ceramica Cleopatra, where he spent the 2022-23 season, before signing for El Masry in August 2023.

It is approaching a month since Refaat passed away, and those left behind are still trying to process what happened and why. There are troubling questions over the circumstances that led to his death, but this remains, at its heart, the tragic story of a man taken far too soon.

During his television interview, Shawky described Refaat as a “great player and a respectful person… he really didn’t like trouble.” The agent said he “blamed myself” for what happened to him, though that was in relation to the decision to join Future FC rather than go to the UAE.

“On paper it seemed like a good move, very,” he reflected when asked about Refaat’s association with Future. “But now and here with you, I believe it wasn’t the right move.”

Shawky became tearful. Refaat’s brother, Mohamed, seemed angry. “We’ll get justice for what happened to him,” he vowed.

It remains unclear how, or whether, that will be served.

(Top image: Matthew Ashton – AMA/Getty Images; design by Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here