After almost nine years in charge and seven major trophies, Jurgen Klopp is leaving Liverpool.

He has been one of the most transformative managers in the club’s history and in English football’s modern era.

To mark his departure, The Athletic is bringing you the Real Jurgen Klopp, a series of pieces building the definitive portrait of one of football’s most famous figures.

In part four, Simon Hughes speaks to people on Merseyside about his impact on Liverpool and the region.

The Real Jurgen Klopp, a series from The Athletic

Mike Kearney was born with sight problems and has been registered blind since he was seven years old.

He was 24 when Klopp was appointed as Liverpool’s manager and 27 when, overnight, he became a recognisable face across the club’s fanbase.

This was because of a video that captured him reacting to Mohamed Salah’s goal against Napoli in the Champions League, which secured progress from the group stage of a competition they would win at the end of the same season.

Amid the bedlam of the Kop, Kearney was filmed on the front row celebrating, before his cousin, Stephen, leaned over and described the goal to him.

A blind Liverpool fan celebrates Mo Salah’s goal against Napoli as his mate describes it. ❤️ https://t.co/EuUMhSgU4T

— Footy (@Footy) December 14, 2018

Within 24 hours, Kearney’s world had changed. Salah saw the clip online and invited Kearney to Melwood, Liverpool’s old training ground, where he met most of the players and the coaching staff, including Klopp.

“As a disabled person, at the back of your mind, you are always wanting to be accepted,” Kearney tells The Athletic. “The experience made me feel accepted by the club I support.”

He remembers Klopp appearing at the top of the stairs at Melwood as he waited in the reception area. The manager came down straight away, even though Kearney got the impression he was supposed to be heading towards another part of the facility.

“No cameras were rolling and he wasn’t trying to be anyone but himself. When you get that respect from a person everyone loves, it makes you feel great.”

Kearney, who has been attending Liverpool matches since he was a child, became a part of the Liverpool story in a remarkable campaign that also almost resulted in the club’s first league title in 29 years, but he is not alone in feeling a bond with Klopp.

For all his trappings as one of the modern game’s super-coaches — the tactics, the signings, the man-management — a key reason Klopp is so celebrated at Anfield has been his ability to connect with the supporters and their city.

Many managers claim to have a bond with their club, to understand its people and practices; listen to the fans Klopp encountered over his nine years in charge and it is clear that with him, it felt real.

“People laugh at the whole turning doubters into believers thing, but it’s true,” Kearney says, referencing the most famous line Klopp uttered at his inaugural press conference in October 2015.

Kearney remembers Borussia Dortmund’s incredible victory over Malaga in the Champions League in 2013, when they scored twice in stoppage time to progress to the semi-finals, and telling himself Klopp would be good for Liverpool. Under his predecessor, Brendan Rodgers, Liverpool had lost 3-0 at home to Real Madrid with three first-half goals, when, according to Kearney, “the attitude was, ‘What can you do, it’s Real Madrid?’.”

He continues: “Under Klopp, there has never been a sense of that. Instead, the attitude has been, ‘I don’t care who you are, you’re on our pitch and we’ll try and beat you, whoever you are’.”

Mike Kearney, one of many fans who felt a bond with Jurgen Klopp (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

Kearney’s condition is degenerative. He used to wear glasses and had more central vision, but now his sight is blurred. These problems accelerated from 2010 onwards, just as he was entering adulthood, and it was becoming harder for people like him to get the support they needed under successive Conservative UK governments.

“There has been a constant necessity to prove that I am disabled enough, that I’m entitled to the help I’ve been getting,” he says.

He blames the political landscape for this. Amid a wider leadership vacuum, Kearney says it helps that Liverpool have had someone managing the club he believes in.

“Liverpool is a left-leaning city and Klopp has left-leaning values,” he says. “He’s never said something and done something completely different and that consistency is important to people in Liverpool.

“I thought we’d won the lottery when we got him, but never in my wildest dreams did I think we’d end up winning it all.”

Kearney says Klopp has harnessed an anger and frustration that bubbles away inside Anfield. When this has happened, the combination has been irresistible, such as when Liverpool overturned a three-goal first-leg deficit to knock Barcelona out of the Champions League in 2019.

Kearney would later analyse the footage of the Barcelona dressing room at half-time, when they were behind in the game but still leading 3-1 on aggregate.

“Everything was still in their hands,” he says. “They were one of the best teams on the planet. They had one of the greatest players the game has ever seen. Yet some of the players were almost in tears. They could see what was coming. When Anfield is like that, you have no chance. And deep down, they knew. A lot of that energy was down to Klopp.

“When all is said and done and the smoke has cleared, and he’s gone, we can only be thankful.

“Fans of other clubs might say you’ve only won one league title and a Champions League under Klopp, but they didn’t live it. We did live it and we had a boss time.”

Klopp has taken Liverpool to three Champions League finals and at the end of the season when they reached the first, a report by Deloitte revealed that during the 2017-18 season, the club had contributed £497million ($628m) to the region’s economy based on gross value added (GVA, a measure for understanding the financial impact made by a business or industry).

The same report established that the club’s activities, and success, had helped create 4,500 jobs in the city.

A competitive Liverpool FC, then, is important to the region — and the influence of Klopp has been significant in the lives of lots of people.

Quietly, he would travel with a civic delegation to Hamburg to discuss trade opportunities between the two cities, which — as football-mad, working-class ports with a strong alternative ideology — have much in common.

Steve Rotheram, the metro mayor for the Liverpool city region, has spent time in the company of Klopp, who he believes would be a leader in industry if he wasn’t a football manager.

Klopp, in Rotheram’s eyes, is a social democrat in the German political tradition. It is these values that fuse well in Liverpool, once one of the biggest ports in the British Empire, where the political landscape shunted from right to left in the 1980s due to crippling unemployment and is not showing any signs that it will ever go back.

Steve Rotheram, the Liverpool city region metro mayor, at his office overlooking Albert Dock (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

Despite an intense local pride, Rotheram says you don’t have to be from Liverpool to lead a Liverpool institution and for people to follow you. Bill Shankly, born in Ayrshire, was proof of that when he revolutionised Liverpool FC following his 1959 appointment, instilling a set of working values and expectations that are subconsciously enshrined to this day.

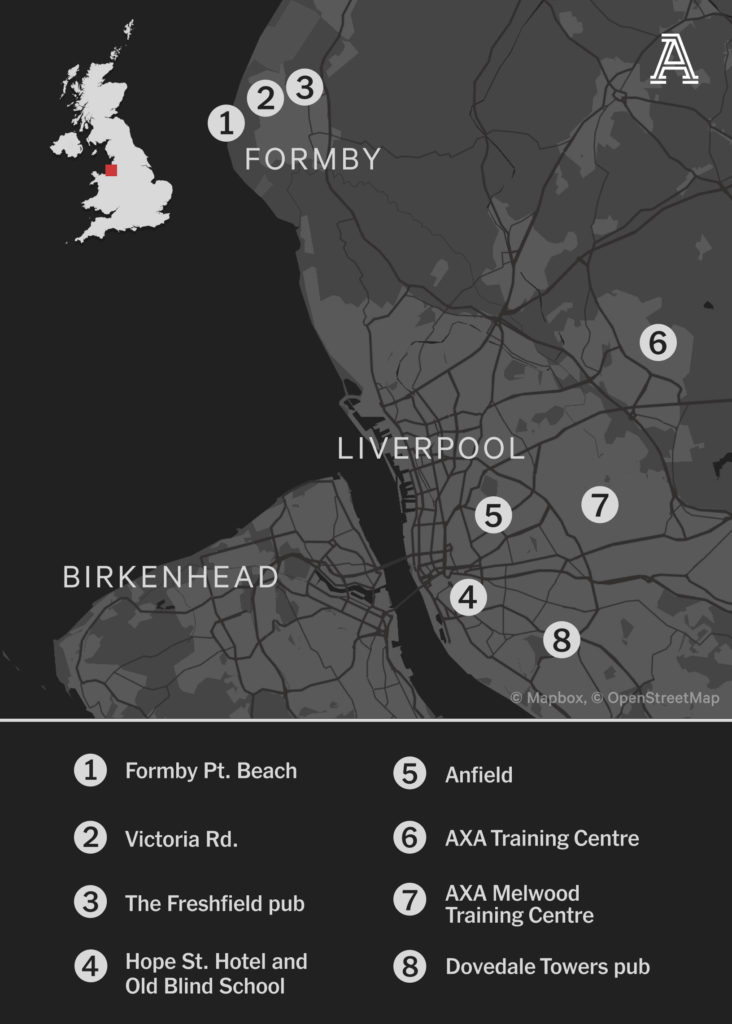

While Shankly’s comparatively modest home was in West Derby, close to Melwood, Klopp has lived on ‘Millionaire’s Row’ in Formby, a leafy seaside town 14 miles north of the city where many Liverpool and Everton stars have taken residence over the years. Klopp inherited his house from Brendan Rodgers and Steven Gerrard was a neighbour.

Most of his time in England has been spent shuttling between his home and Liverpool’s training grounds – first at Melwood and, more recently, the AXA Training Centre in Kirkby, a half-hour drive away. He has not been as visible in Liverpool as Shankly, who used to drive his garishly coloured Ford Cortina through the traffic and into the city centre to go shopping.

‘Millionaire’s Row’ in Formby where Jurgen Klopp has called home (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

Yet times have changed and the attention on any particularly successful Liverpool manager means it is more difficult to live the normal life Shankly once led.

The night before he was unveiled as Liverpool manager, Klopp was photographed having a drink in the Old Blind School restaurant in the city’s Georgian quarter.

Maybe it was then that he realised the attention on him would be hard to escape. Ever since, if Klopp has gone out, it is usually within Formby, where he has regularly been sighted at the Freshfield pub (including at the venue’s quiz night) and the town’s pinewoods and beach, where he walks his dog. In 2016, he also took part in a game of crown green bowls at the local club.

He has been spotted at the Sparrowhawk pub and restaurant in Ainsdale, too, and was a regular at the Hope Street Hotel, a boutique establishment in the city centre, after choosing it as Liverpool’s official pre-match base.

On one occasion, he was spotted in the south end of Liverpool, at the Dovedale Towers, but that was because he was filming an advert for Erdinger, the German beer company who are one of his sponsors.

In 2009, Shankly was posthumously made an honorary citizen of Liverpool, 28 years after his death. Yet Klopp, in 2022, was awarded with the freedom of the city while he was still the club’s manager.

This was a first and, according to Rotheram, when he speaks to The Athletic from his Mann Island office overlooking Liverpool’s Albert Dock, “it shows you the type of principles he has and it shows you they have resonated with people”.

Rotheram speaks of a “spiritual connection” between Klopp and the city. “I’ve never known a Liverpool manager that fans of rival clubs will at least say neutral things about. Yet he dovetails with Liverpool and Merseyside better than anyone I’ve known. And if he went to another club, I’m not sure he’d experience the same synergies that exist here.”

With Mayor for Manchester Andy Burnham, Rotheram has recently co-published a book called Head North: A Rallying Cry for a More Equal Britain.

As a politician, he says he has encountered an anti-Liverpool bias in the committee rooms of Westminster, where MPs from other parts of the country would speak about representatives of Liverpool showing up in London with their “begging bowls”.

The Freshfield pub, where Jurgen Klopp is a regular (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

Rotheram has tried his best to shift this perception, which is layered in an anti-Irish sentiment dating back to the 19th century when immigrants from the country would arrive on boats from Dublin and elsewhere, and he says Klopp has helped with that process.

“I don’t think Jurgen has ever pretended to know all of the city’s history, but he knows enough to defend it,” says Rotheram. “He realises his words and actions transcend what happens on a football pitch.”

Ian Byrne grew up in Liverpool’s Cantril Farm estate before moving to the Anfield area, but as a member of parliament, he represents the nearby West Derby ward.

Aged 16, he was at Hillsborough in 1989 when 97 Liverpool fans lost their lives at the FA Cup semi-final against Nottingham Forest. Though Byrne escaped the crush, his father was seriously injured.

In 2015, he co-founded the Fans Supporting Foodbanks initiative with Dave Kelly, an Evertonian.

Like Rotheram, Byrne sees the Liverpool manager’s job as one that extends to civic duty, “adding another layer to the long list of responsibilities — any manager has to embrace it, whether fair or not”.

Byrne says Shankly is “completely responsible” for the culture at Liverpool where the manager’s word is sacred. Yet some of his successors have had greater challenges than merely raising a football club, as Shankly did, taking Liverpool from the old Second Division to the pinnacle of the English game.

From 1989, each manager has needed to deal with the impact of Hillsborough. Kenny Dalglish was in charge at the time of the disaster and he attended many of the victims’ funerals, including four in one day. He is almost as celebrated for that as he was for his stellar achievements as a player and manager.

“You’ve got leadership on the football pitch, but you’ve got to show it off the pitch as well,” says Byrne. “People expect you to stand up for the city. It takes a special person to be successful at this job.”

Street vendors in Liverpool sell Jurgen Klopp merchandise (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

Klopp’s “global voice” has given Liverpool a wider audience, according to Byrne, who believes that sometimes, Liverpudlians have to fight “three, four or five times harder, just to make sure our voices are heard”.

This is due, he says, “to preconceptions about who Liverpool people are and what they can achieve”.

Byrne stands in front of a recently painted mural, which marks Klopp’s tenure at Liverpool. There are several like these in Anfield now, including those players from the Klopp era regarded as legends.

The club’s relationship with the local population in Anfield is better than it was 15 years ago when there remained uncertainty about whether the club would stay or relocate.

The lack of permanence ensured the district suffered, but now, with the Anfield expansion — in which the success of Klopp’s teams has played a part — the mood has improved, though the relationship is not without its problems.

Byrne, a season ticket holder at Anfield, says that, for a long time, the “Liverpool machine” was considered the enemy by many, but under Klopp, there has been a mindset change at ownership level.

On a matchday, there remains anxiety due to the number of people entering the area and an increase in anti-social behaviour. Meanwhile, the interest in the fortunes of Liverpool has led to an explosion of rented accommodation options and ‘lad-pads’.

Ian Byrne, the MP for West Derby, by a Klopp mural in Liverpool (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

Byrne says the terraced Victorian houses of Anfield would be ideal first-time buyer homes, but the economic position of an area that remains one of the poorest in Liverpool means families are reluctant to move in.

Klopp, adds Byrne, cannot be judged on the position of a district that has long struggled, but he has done his best to deliver a world-class team and the benefits of this should be highlighted.

Pointing up at the mural, he insists Klopp is the closest manager Liverpool have had to Shankly.

“And I did not think that was possible.”

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here