On the edge of Amsterdam’s vast Schiphol airport, the sonic roar of engines audible in the distance above the field of sunflowers swaying in the breeze, the relatives of flight MH17 gather in the memorial garden created at Vijfhuizen. They are here for an emotional, moving ceremony to mark the 10th anniversary of the aeroplane’s shooting down over Ukraine. All 298 travellers and crew were killed.

It is sombre and tearful as families walk through the 298 trees planted in the name of each one of the victims. Fresh flowers are laid, photographs taken, the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra plays beautifully and Piet Ploeg, the families’ representative, makes a dignified and quietly angry speech to those in the garden’s amphitheatre. “You have all shown you have the patience and civilisation to go through this miserable process,” he said.

The Netherlands’ new prime minister, Dick Schoof, is present, as is the Dutch King, Willem-Alexander. Australia’s attorney-general, Mark Dreyfus, also speaks.

This is the Netherlands’ great modern national trauma; of the 298 killed — 283 passengers and 15 crew — 196 were Dutch. Television has been replaying 2014 footage of the ‘endless procession’ of cars taking the repatriated bodies from Schiphol to Hilversum for identification.

There were 43 from Malaysia killed, including the 15 crew, and 27 from Australia. Eighty of the dead were children. The flags of 17 countries fly at half-mast.

Flags reflecting the nationalities of the victims fly at half-mast (The Athletic)

There were 10 victims from the UK and two of them, John Alder and Liam Sweeney, were fans of Newcastle United. They were on the flight because Newcastle had arranged their 2014-15 pre-season tour in New Zealand and a 24,000-mile round trip was not going to deter them from seeing their team.

This is what attaches English football to the violation stimulated by Vladimir Putin’s aggression in Ukraine, which, this reminds us, is 10 years old, not two. Football may also wish to remember FIFA allowed Russia to stage the 2018 World Cup four years after what happened to MH17.

At first, Russia’s separatists on Ukraine’s eastern border celebrated the downing of an aircraft, as did some of Moscow’s state media. But when it became clear this was not a Ukrainian air force plane but a civilian Boeing 777, the backtracking began and the evasion has continued as the MH17 families and a Dutch-led Joint Investigation Team have pursued Russia through the courts to force them to accept responsibility.

In 2016, the investigation concluded the plane was shot down by a Russian Buk missile launcher supplied by Russia to a proxy militia, this one led by Igor ‘Strelkov’ Girkin. One English translation of Strelkov is ‘shooter’.

In 2022, Girkin and two others were found guilty in a Dutch court. Girkin, in Russia, refused to accept the verdict. On Tuesday, the European Union released a statement saying it “reiterates its call on the Russian Federation to accept its responsibility in this tragedy and to cooperate fully in serving justice”.

It is unlikely Putin’s regime will ever accept its role.

But then it was not represented in Vijfhuizen. One of the Dutch lost on July 17, 2014 was Quinn Schansman. He was just 18 and had dual United States citizenship. At 2.44pm his father, Thomas, was one of those who read a roll-call of the dead. Everyone’s age was also read out.

Twenty-five minutes in came the names of Alder, 63, and Sweeney, 28. In this era of the performative fan, neither sought such prominence. Alder in particular was a reticent man who would not have wanted this, just as in the days after his death he would not have enjoyed people speaking about his devotion to Newcastle United, a passion that meant he missed one domestic match in 50 years. It was Watford away in 2006 if you care, and he did.

Over half an hour as each name and second passed, and the readers’ voices broke, the enormity of the human loss grew. It took 31 minutes and 22 seconds to read out every name.

A lot has changed since July 2014 — internationally, politically and at Newcastle United; our awareness of Russia and Ukraine has grown. Place names such as Bucha, Mariupol and Kharkiv have a familiarity and meaning they did not possess a decade ago. Then, Kharkiv was the home of the Metalist club Newcastle faced in the Europa League in February 2013. Alder was there that night.

Alan Pardew was Newcastle’s manager under the ownership of Mike Ashley and in mid-July 2014, as MH17 was prepared for take-off, Newcastle were organising deals for Mathieu Debuchy to leave for Arsenal and Daryl Janmaat to arrive from Feyenoord.

It feels like a different era — long before the 2021 Saudi Arabia takeover — because it was, and while such transfer details may seem inconsequential, they mattered to fanatics like Alder and Sweeney.

Inevitably, though, as years and seasons pass, those details are overtaken and the surnames of Alder and Sweeney fade from view.

For a long time, Liam’s name was kept alive by his father Barry, supported by the Tyneside media. Barry was a well-known local referee and somewhere in Newcastle United’s archive is a photograph of him taking charge of one of the club’s junior games. In the background is his son Liam — and John Alder. Liam was there in part to watch his father; John was there because he was always there. Sadly, Barry Sweeney died last August, aged 61.

Newcastle United reacted in 2014 with Pardew and his captain Fabricio Coloccini laying wreaths on two empty seats at the stadium in Dunedin where the two fans were due to watch their team. At St James’ Park, the club constructed a small memorial adjacent to the main Milburn Stand. After a family request, there was a low-key wreath-laying there today. The club’s foundation also has an annual Alder-Sweeney community award.

Alan Pardew lays wreaths in memory of Liam Sweeney and John Alder (Marty Melville via Getty Images)

Low-key was certainly in keeping with Alder’s personality. For a while after the traumatic attack, Newcastle fans broke into applause in the 17th minute of games which, according to those who knew him, might have made Alder’s head shake. So would the fact supporters of Sunderland, Newcastle’s rivals, set up an online fundraiser to get £100 for two wreaths and surpassed £30,000.

Sweeney worked in a Newcastle branch of Morrisons supermarket. Alder worked for British Telecom, was not married, had no children, his parents were gone and his sister was as reluctant in the public eye as he was. But Alder, like Sweeney, merits attention as a member of a football fan culture in an area deeply affected by football. They were travelling to the game because it’s what they did.

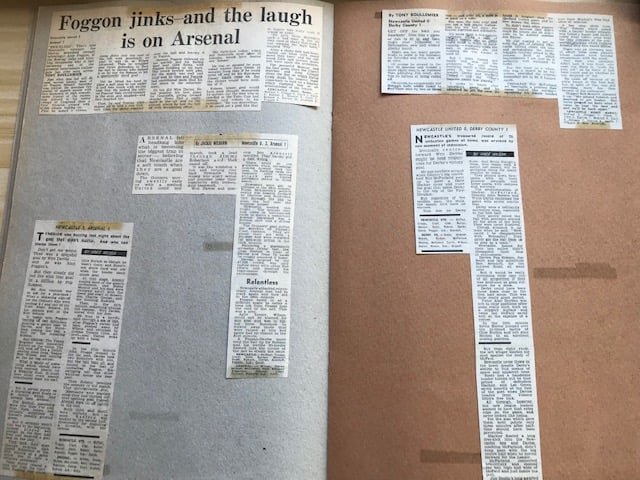

“John was a football fundamentalist, in my eyes that’s the best way to describe him,” says Michael Bolam in his Tyneside house, where he has some of the personal memorabilia Alder amassed since he first started keeping scrapbooks in 1964.

John Alder’s love for Newcastle meant he kept scrapbooks filled with newspaper cuttings (The Athletic)

“He watched football as a spectator with no idea other than that the spectacle was the 22 players on the pitch. Minutes’ silences, people who turned up late, people who left early, it all irritated John. There was this idea that he was a ‘superfan’, which is a term he would have hated. He didn’t like people who used football for their own publicity or their own ends. He never wore a replica jersey, because he would never have bought one.

“And now this is in his name. The people who knew him are like… that’s not what John’s attitude was. If John wanted to give to charity, he did it in private. He didn’t want applause in the 17th minute or anything like that.”

Yet it came. Alder was known among a certain section of supporters: always dressed in a black suit with a white shirt, he was affectionately called ‘The Undertaker’. He was there, two nights before MH17 took off from Amsterdam, at Oldham Athletic. Bolam, who has run the nufc.com supporters’ website since the 1990s — known to most as Biffa — was also present.

“Yes, he was there among a handful of supporters for the first pre-season game at three-sided Boundary Park,” Bolam says. “I can still see John now. He was there early, just a nod, an acknowledgement. It was the last time I saw him.

“He was an undemonstrative, genuine man who loved watching Newcastle. He and Liam didn’t travel together — Liam used to go to away games on supporters’ buses and stewarded on them; John would never have gone on a bus because he would have feared not getting there for kick-off.

“But they are bound together now.”

And they are. In Vijfhuizen beside the sunflowers — grown from seeds gathered in the fields of Ukraine where the plane debris was found — the 298 trees are laid out in rows. Alder and Sweeney have been placed side by side, numbers 223 and 224. A small marker, possibly laid by his father Barry on a previous trip, is at the base of Sweeney’s tree. ‘Made in Newcastle’ it says, ‘100% Geordie’.

The memorials to Liam Sweeney and John Alder (The Athletic)

“We’re no nearer, 10 years on, to understanding it,” Bolam says. “Someone I used to go to the match with was killed on the orders of Vladimir Putin — how do you process that? It’ll be similar for all the families. It’s otherworldly.”

On a distressing afternoon, amid the grief and trees and tears and sunflowers, it must have felt that way to so many relatives, and yet it is of this world. The speakers restated that the quest for justice will continue.

(Top photo: Getty Images)

Read the full article here