Frank Lampard was out with friends recently when they got talking about the good old days, as tends to happen once you reach a certain age.

“It was that typical thing,” the former Chelsea and England midfielder, 46, tells The Athletic, “where you’re chatting with mates and they’re moaning that football is more boring than it used to be.

“And the general things they say are that, 1) the tactical element has made it more boring and, 2) the players aren’t as good as they were in our day when there were all these players that we loved watching and…”

And he gets it. As one of the icons of the Premier League era, Lampard is better placed than most to reminisce about those years between the mid-1990s and the mid-2010s: show-stopping superstars like Thierry Henry, Cristiano Ronaldo and Didier Drogba, midfield warriors like Roy Keane, Patrick Vieira and Steven Gerrard, managerial giants like Sir Alex Ferguson, Jose Mourinho and Arsene Wenger, big personalities, bitter rivalries, box-office clashes, daunting trips to Blackburn, Bolton and Stoke in the howling wind and driving rain and the feeling, amplified by hindsight, that it was a golden age.

There are times when, like many of us, he feels it: times when he sits down to watch a big match, “when you’re having a beer and you’re looking forward to it”, and the spectacle can be a bit…

Boring? No, Lampard bristles at the suggestion. He doesn’t find modern football boring. From a coaching perspective, he finds it fascinating, studying the demands placed on today’s players — even the goalkeepers — in build-up play compared to 20 years ago, let alone the decades before that.

He talks about analysing how the modern-day Manchester City build up under Pep Guardiola — “seeing Rodri dropping back into his own box and taking the ball and giving it in areas where I would never have wanted to do that as a player” — and how every team these days, to some degree, tries to play that way.

Lampard contrasts that with seeing footage from his heyday at Chelsea recently and, with his coach’s hat on, “almost cringing” at how rudimentary some of the football is. “Big Petr (Cech), up to Didier (Drogba), second ball and then we’re up there,” he says, laughing.

(Richard Heathcote/Getty Images)

But that is the difficulty, the former Chelsea and Everton manager explains, in trying to evaluate the football of yesteryear through a modern lens — and vice versa.

Go back another 20 years and you would hear former players saying that Keane and Vieira wouldn’t have lasted five minutes with the hard men of the 1970s like Tommy Smith, Ron “Chopper” Harris and Norman “Bites Yer Legs” Hunter.

“And I would never want to sound like that dinosaur that says, ‘Oh, everything was better in my day,” Lampard says. “It’s opinions, isn’t it?”

The past few months have brought waves of nostalgia for a previous era in English football.

The Cultras Football Podcast was behind the #barclaysmen social media trend, showcasing certain players — usually a star turn at a less glamorous club, like Jay -Jay Okocha at Bolton Wanderers, Yakubu at Portsmouth or Morten Gamst Pedersen at Blackburn Rovers — who is felt to have captured the zeitgeist of the early 21st-century Premier League (which was then sponsored by Barclays Bank, hence #barclaysmen).

We had to jump on this trend with the most quintessential #Barclaysman of them all 😅

Morten Gamst Pedersen x The Subways 🎶#Barclaysmen | #Rovers 🔵⚪️ pic.twitter.com/lb1dE6v6FE

— Blackburn Rovers (@Rovers) September 10, 2024

At the risk of looking too deeply into these things, the Barclays era (not to be confused with the Barclaycard era) ran from 2004 to 2016, at which point the Premier League decided its global brand had become so powerful that it no longer needed a title sponsor.

In other words, it stretched from the start of the 2004-05 season (the arrival of Jose Mourinho at Chelsea, the end of Arsenal’s “Invincibles”), through the “Big Four” era of the mid/late 2000s, all the way up to Leicester City’s remarkable title success in 2015-16 and stopping just short of Guardiola’s arrival at Manchester City.

A golden era? Some would say so, pining for an age when every heavyweight tussle was a grudge match and the YouTube compilations would have you believe every goal was a 25-yard screamer from a floppy-haired maverick wearing a baggy shirt.

Or, as former Tottenham and Wolves midfielder Jamie O’Hara put it earlier this year, “Seriously, take me back to the early 2000s. Lampard, Scholes, Gerrard, Stoke on a Tuesday night, Crouchy (Peter Crouch) doing the robot. What the hell happened?”

Blue cards getting introduced the game has absolutely gone, seriously take me back to the early 2000s, Lampard scholes Gerrard, stoke on a Tuesday night, crouchy doing the robot, what the hell happened

— Jamie Ohara (@Mrjamieohara1) February 8, 2024

What happened? We got older. And the game evolved, becoming less attritional and more refined — continuing a direction of travel that can be traced back as far as anyone can remember.

The theme cropped up last month when The Athletic revisited one of the most famous — or infamous — games of the Premier League era.

It was the 20th anniversary of the match known as the “Battle of the Buffet”, so-called because Arsenal midfielder Cesc Fabregas lobbed a pizza at Ferguson during a post-match tunnel fracas. But if there was a pantomime aspect to that particular incident, it was, looking back, the type of game that might require an R certificate for today’s TV audiences.

Phil Neville knows that better than most. He recalls that game as one of his best for Manchester United but is acutely aware those of an Arsenal persuasion remember his involvement — and that of his brother Gary — very differently.

Both Nevilles were shown the yellow card in the first half for fouls on Arsenal’s young Spanish forward Jose Antonio Reyes, but both should have been booked much earlier. Phil Neville admitted it was a game “where you just use the dark arts of football”, “a game where I think we probably, at times, overstepped — no question about that.”

Gary Neville lunges through the back of Reyes (Stuart MacFarlane/Arsenal FC via Getty Images)

“It’s a different type of football nowadays,” he said. “I saw a clip on Instagram the other day from a Community Shield game where there were so many bad tackles you would be left playing a five-a-side game if it was today — and none of those tackles were even getting yellow cards. People get sent off now for challenges that wouldn’t even have been a foul 10 years ago.

“It’s a totally different era — and not just refereeing but TV scrutiny, punditry, social media. If that ‘Battle of the Buffet’ game was now, there would be people complaining in parliament — ‘It’s a disgrace to football.’ ‘It’s a disgrace to the world’ — whereas back then it was just a brilliant game of football.”

Arsenal fans might disagree as vehemently now as their former manager Wenger did 20 years ago. But the thrust of Phil Neville’s argument is correct. In isolation, the challenges on Reyes were not particularly grievous by the standards of the time. What infuriated Arsenal was the number of fouls on Reyes before a yellow card was shown, something that Gary Neville, in his autobiography, put down to a desire to “intimidate” his opponent.

Physical intimidation had long been part of football in England in particular. It was on the way out by the mid-2000s, and it was low-level stuff compared to what had been permitted in previous decades, but it was fearsome by today’s standards.

Just how much the game has changed was reinforced while rewatching that “Battle of the Buffet” game: most obviously the physical challenges but also the frequency with which the ball was lost.

Vieira’s first pass, five seconds into the game, went straight to an opponent. Seconds later, Cristiano Ronaldo slipped and lost the ball to Reyes. Arsenal full-back Lauren hit a long ball straight onto the head of Mikael Silvestre. Gary Neville saw a clearance charged down by Reyes. A misplaced pass from Paul Scholes sent Ronaldo scurrying towards the touchline where he was clattered by Ashley Cole. This all happened within 37 seconds of kick-off.

On it went like that. Four fouls and so many stray passes in the first six minutes. That was before the real rough stuff: Edu crashing into Ruud van Nistelrooy; Gary Neville fouling Reyes three times before the interval; Van Nistelrooy, studs up, taking out Cole just below the knee, which was somehow missed by referee Mike Riley but later punished with a three-match ban for violent conduct.

Gabriel Heinze clashes with Vieira at Old Trafford (Paul Barker/AFP via Getty Images)

Riley let far too much go but still blew for nine fouls between the 25th and 37th minute. In total, he awarded 44 fouls and showed five yellow cards throughout a volatile game. Both of those totals should have been considerably higher.

It was a match of its time. Since Opta began recording such data in 2003-04, there have been 13 Premier League games with at least 46 fouls… and all 13 were between 2003 and 2007 — and that was when the threshold for foul play was far higher than now. Pure Barclays, you might say.

“I don’t like comparing eras,” Phil Neville says. “If you look back at those games back then — just taking the Manchester United vs Arsenal games — you cannot get games like that now. It’s physically impossible for the players to play like we did back then.”

Equally, he points out, the level of physicality permitted in the 2000s was far less than that seen in previous decades, when “people were throwing punches on the pitch and getting yellow cards”.

“It was a totally different game by the time I was playing,” he says, “and it’s totally different again now.”

Phil Neville isn’t advocating a return to the days when players could kick lumps out of each other. (For the record, the team he coaches, Portland Timbers, have one of the better disciplinary records in Major League Soccer, as did his Inter Miami team previously.)

But he does feel that sport’s appeal is enhanced by fierce rivalries of the type that soared in English football in the 2000s… but seem almost alien to the more sanitised Premier League environment of today.

It is why he found himself enthralled in September by Arsenal’s 2-2 draw at Manchester City, a rare game that combined modern technical finesse with the box-office tension and, yes, the belligerence and spite of a bygone era. “That was like the games we used to play in,” the former England international says. “That got my juices flowing.”

Haaland rises highest to win a header against Arsenal in September (Robbie Jay Barratt – AMA/Getty Images)

There was a box-office element to those rivalries in the 2000s — not just Manchester United vs Arsenal but Chelsea vs Arsenal, Chelsea vs Liverpool, Manchester United vs Liverpool, big personalities on the touchline and all over the pitch.

There was excitement in Phil Neville’s voice as he recalled the Manchester United vs Arsenal games: the “boiling” tension between the two managers and the two sets of players, the feeling that everything was on a knife edge, that “it was going to be box-office on and off the pitch”, that “at any moment somebody could have just taken the pin out and it could have just exploded”.

But here’s the thing that is too easily forgotten in the haze of nostalgia. The prevailing football doctrine of the 2000s meant the games were often — not always, but often — tight, cagey affairs.

There were some classics between Manchester United and Arsenal (the FA Cup semi-final replay in 1999 perhaps the ultimate) but, at times, the antagonism and the fear of losing overshadowed everything. Two fiercely contested games at Old Trafford, in 2003 and 2004, are remembered for the aggro rather than for the football. There was enormous hype around Liverpool vs Manchester United clashes, but the matches were often dire.

Liverpool and Chelsea met 16 times in all competitions between August 2004 and August 2007 when they were managed by Rafael Benitez and Mourinho respectively. Of those 16 matches, 10 featured one goal or fewer. The phoney war between the managers might occasionally have been “box office” but the football was rarely anything of the sort.

Mourinho and Benitez were responsible for some dire matches between Chelsea and Liverpool (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images)

A succession of Liverpool-Chelsea stalemates in the Champions League in the mid-2000s — six matches, three 0-0s and three 1-0s — memorably prompted former Real Madrid and Argentina forward Jorge Valdano, one of the game’s great romantics, to liken the spectacle to “s*** hanging from a stick”.

Chelsea and Liverpool, he wrote in Marca, were the “clearest, most exaggerated examples of the way football is going: very intense, very collective, very tactical, very physical and very direct. But a shot pass? Noooo? A feint. Noooo. A change of pace? Noooo. A one-two? A nutmeg? A back heel. Don’t be ridiculous. None of that.

“The extreme control and seriousness with which both teams played the (2007 Champions League) semi-final neutralised any creative licence, any moments of exquisite skill.”

The 2007-08 season is popularly regarded as a peak of excellence in the Premier League. It was a campaign in which Manchester United and Chelsea reached the Champions League final in Moscow, when Cristiano Ronaldo earned his first Ballon d’Or and players like Rio Ferdinand, Nemanja Vidic, Wayne Rooney, Lampard, Gerrard and Fernando Torres were around the peak of their formidable powers.

It was also the season in which the number of passes per game in the Premier League fell to 717, its lowest point since Opta records began. That figure picked up over the next few years, hovered around the late-800s mark for a time and held firm in the 900s as Guardiola’s influence has spread (although, curiously, this season to date has seen a slight drop to 896 passes per game, the lowest since 2016-17).

That might sound like a relatively small difference, 717 passes as opposed to 900-odd over the course of 90-plus minutes, but pass completion offers a starker illustration of how playing styles have evolved. In 2006-07, it stood at just 69.8 per cent, but it has risen almost every year since and is this season at an all-time high of 83.7 per cent.

The team with the lowest passing accuracy in this season’s Premier League is Everton, but their 74.8 per cent pass completion rate is higher than all but four teams managed in 2006-07. Twelve out of 20 teams this season, including newly-promoted Leicester City and Southampton, have a higher pass completion rate than the highest back then (Arsenal with 80 per cent). Watford completed just 55.7 per cent of their passes in 2006-07, adopting a style that seemed mildly regressive at the time but would look totally primitive today.

In so many ways, it is a different game now.

This time last year, former Liverpool and England forward Michael Owen appeared on the Up Front podcast, hosted by former Crystal Palace chairman Simon Jordan.

Jordan asked him whether, in terms of individual excellence, he felt the standard required to win the Ballon d’Or is higher than when he did so in 2001. “I would actually go the other way,” Owen said, sounding affronted by the suggestion.

“Back in the day, there were loads of great players that were absolute ballers, proper proper talented. Now if you can just run a bit further than everyone else and you can basically pass the ball from A to B, you’re getting a decent career in the Premier League. You don’t even have to be that good anymore.”

It is a popular opinion. It also seems a pretty blinkered one. Owen was a brilliant footballer, as were some of those he played with for club and country, but he also had team-mates whose skill sets would look horribly out of place in the modern game; to put it kindly, there was a dearth of “absolute ballers” at Liverpool in his final couple of years there. He played alongside Luis Figo, Zinedine Zidane and the original Ronaldo at Real Madrid, but that team also included Thomas Gravesen — highly effective in that era but again far from the “pure footballer” of Owen’s description.

Look at how technically gifted some of the players emerging from Premier League academies are. And in most cases, it is still not enough to make it at Premier League level because, with clubs able to attract the best talent from all over the world, the required standard — technical, physical, mental, tactical — is so high.

The question of changing technical standards was discussed by former Manchester United and England defender Ferdinand last week on a podcast with former Chelsea midfielder, under-18s coach and assistant manager Jody Morris.

Ferdinand was explaining his disappointment at Rodri’s recent Ballon d’Or triumph, saying the award should go to a more flamboyant player like Real Madrid winger Vinicius Junior. Like a true #barclaysman, Ferdinand was lamenting a lack of eye-catching, creative, get-you-off-your-seat players in the modern game.

Vinicius controls the ball with a flamboyant touch (Jose Breton/Pics Action/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

He asked Morris whether players were better now “or when we were playing”, sounding fairly sure the former Chelsea player would side with him. Morris replied firmly that “the average player now is a lot better than when we were around”, adding that what was lauded as “sexy football” at Chelsea in the 1990s and early 2000s “would be classed as a long-ball team” now.

Morris spoke about the demands on modern central defenders and full-backs, in terms of the risks they have to take by a) defending so high up the pitch and b) playing out from the back, compared to a previous era when full-backs “just booted the ball up the pitch”.

“I think the high-level players back in the day would still be high-level players today,” Morris said. “But some of the footballers that got through and had great careers back in the day, I’m not sure would have great careers now.”

Morris is correct. Whatever is perceived to be missing from the modern Premier League landscape, it is surely not technical excellence.

The more you look at it, the more you come around to the feeling that what is missing from today’s football is not technical quality, creative freedom or anything of the sort. It is personality, both on the pitch and on the touchline.

Keane, Vieira, Gerrard, Henry, Drogba and Rooney were top-class players but they also brought a certain main-character energy that would seem out of place in today’s more system-based football.

Henry celebrates scoring against Arsenal’s fierce rivals Tottenham (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images)

One of the great contradictions of modern football, where the cult of the individual is so strong in terms of image, is that the leading players today are quieter, less demonstrative, less individualistic, more like cogs in a machine. The dominant midfielders in the Premier League over the last year or two — Rodri, Bernardo Silva, Alexis Mac Allister, Moises Caicedo, Declan Rice, Martin Odegaard, Bruno Guimaraes — are not powerhouses or warrior types. They do not scream main-character energy.

But they are top-class players — among the best in the world at what they do. Rodri, arguably the most influential player in the Premier League over the past three or four seasons, has just won the Ballon d’Or. Virgil van Dijk narrowly missed out on the 2019 award to Lionel Messi. Kevin De Bruyne and Mohamed Salah have been part of that Ballon d’Or conversation for years, as Erling Haaland will be if he continues to score goals at such an extraordinary rate.

The difficulty comes when trying to evaluate those players next to the established giants of the Premier League era.

Phil Neville, when he was casting his mind back to those Manchester United vs Arsenal games in the 1990s and 2000s, reeled them off: Gary Neville, Sol Campbell, Ashley Cole, Ryan Giggs, Dennis Bergkamp, Vieira, Keane, Scholes, Rooney, Ronaldo.

“You’re talking about legends,” he said. “Some of the best players that have played in their position in Premier League history.”

Few would disagree with a word of that. But by the same token, Van Dijk must be recognised as one of the great central defenders of the modern era, Rodri one of the great midfielders, De Bruyne one of the great creative talents, Salah a wide forward who consistently scores goals at a rate far beyond what Ryan Giggs, Robert Pires or Cristiano Ronaldo managed in the Premier League. Bukayo Saka, at 23, has twice scored more goals in a Premier League season than Giggs ever did. The heights Haaland and Cole Palmer reached in their first seasons in the Premier League, with Manchester City and Chelsea respectively, were extraordinary.

The obvious riposte — a legitimate one, for the reasons outlined above — is that there are far more goals scored today. For all that Salah or Saka might get kicked by opponents, they will never have to withstand the type of treatment Giggs, Pires or a young Cristiano Ronaldo faced. They also play higher up the pitch in a 4-3-3 formation rather than a 4-4-2, encouraged to cut inside onto their stronger foot rather than stay wide in an orthodox right-wing role. It stands to reason that it is easier to score freely in a league where there are 3.28 goals per game (last season) than 2.45 goals per game (2006-07).

But using that same argument, life must have been easier for central defenders when teams were set up so conservatively, the back lines deeper and more compact, with much more defence-minded players in the full-back and midfield roles, and the laws of the game far more permissive in terms of how to tackle a tricky opponent.

In terms of positioning and use of the ball, Van Dijk, Gabriel, William Saliba, John Stones and others are required to take risks of a type that John Terry, Campbell, Vidic and even such an accomplished ball-playing central defender as Ferdinand never had to — and still, playing on the front foot in a league where the goals flow freely, they contribute to defensive records that stack up favourably against all but the very meanest of the Premier League era.

(Simon Stacpoole/Offside/Offside via Getty Images)

As for Rodri, he has scored hugely important goals while establishing himself as the linchpin of a Manchester City team that has won four consecutive Premier League titles. His influence in midfield might be more understated than that of a Keane, Vieira or Gerrard but it is enormous, as illustrated by the contrast in Manchester City’s results with and without him.

Lampard is emphatic on the matter. “You have to put Rodri among the best Premier League midfielders ever now,” the former Chelsea player says.

“You look at what he does in that defensive area of the pitch, not just defensively but on the ball, and it’s amazing. For me, he has elevated himself to the best midfield player in the world.”

Some former players cling to the belief that the game was more technical in their day, but that argument doesn’t seem to stack up. There was a greater willingness to test the limits of that technique by hitting a 50-yard pass or a 30-yard shot, perhaps, but that does not mean the game as a whole was more technical. The laws and the coaching orthodoxies of the 2000s didn’t allow it.

What is less clear and more open to debate is whether the technical advances of the past 20 years have made for a better game.

There is undoubtedly something in the English sporting psyche that reveres crunching tackles and towering headers over measured possession football. Even in the lower divisions these days, it can feel as if nearly every team is cosplaying Manchester City, every coach a Guardiola wannabe, worried how it might look if their team’s pass completion dips below 75 per cent.

Former West Ham United manager David Moyes warned in 2017 that “If everybody plays the same game, if everybody takes it from the back and passes and we all have to have 25 passes, it will become the most boring game that you could watch”.

There are times when it can feel like that… or like there is a lambs-to-the-slaughter element when a smaller team plays that way against an opponent with a highly drilled counter-pressing game like Manchester City or Liverpool.

But cannot it really be boring when we are seeing many more goals than before — and when there are so many games that swing one way and then the other before a dramatic late winner, as has happened so often over the past few seasons?

Last season’s average of 3.28 goals per game in the Premier League was the highest-scoring top-flight campaign in England since the mid-1960s. The lowest-scoring season of the Premier League era (2.45 goals per game) was 2006-07, which also happened to be the one with the lowest pass completion since Opta began recording such data.

That 2006-07 campaign also featured the most famous BBC Goal of the Month competition in the Premier League era, a series of stupendous strikes from Keith Gillespie, Matt Taylor, Michael Essien, David Bentley, Tom Huddlestone, Paul Scholes, Robin van Persie, Lampard, Drogba and, of course, quintessential #barclaysman Pedersen, several of them the type of long-range blockbuster that seems to have gone out of fashion.

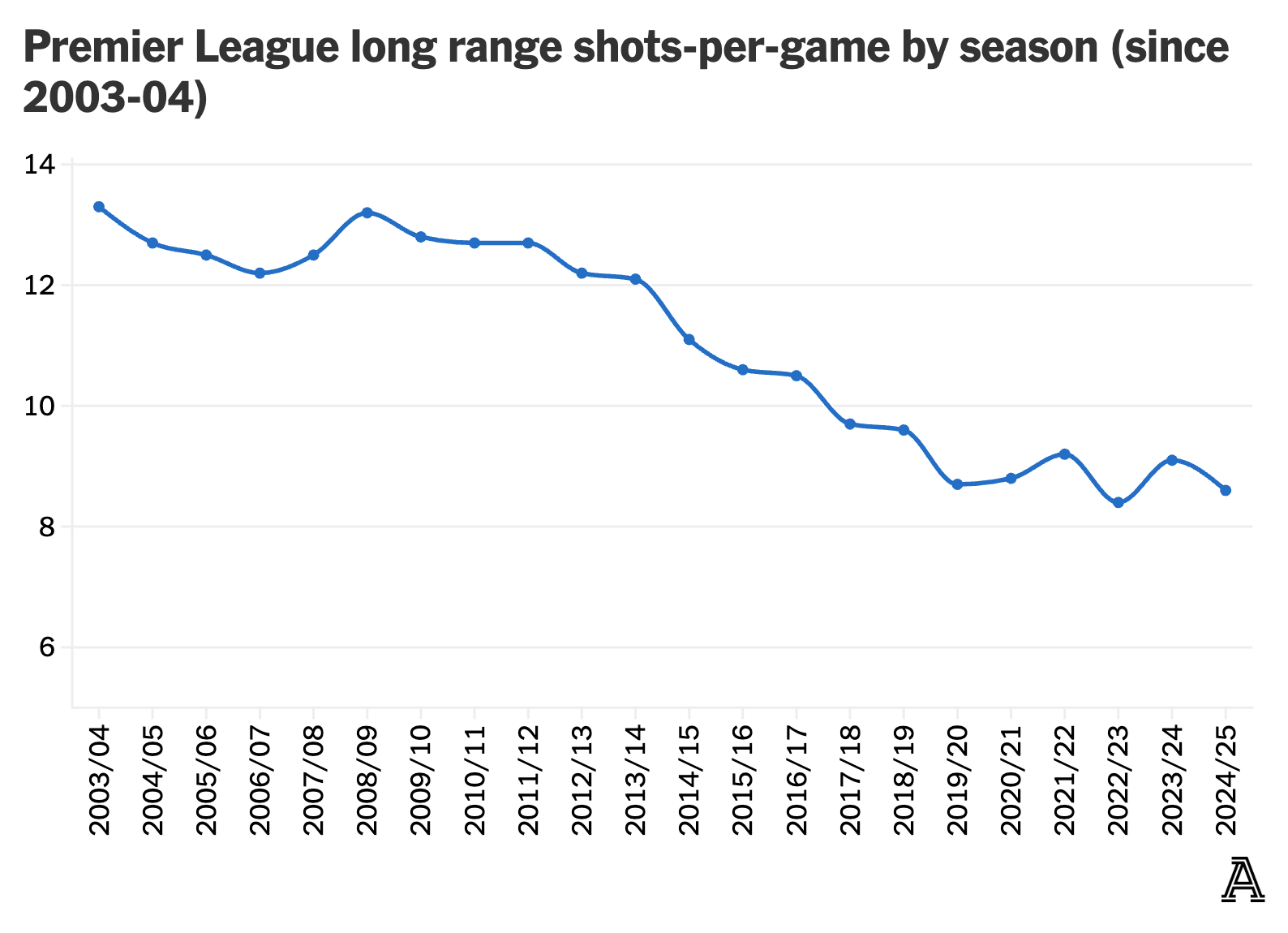

Long-range shooting has declined dramatically in the Premier League since the 2000s.

But a decline in long-range shooting — more in relation to quantity than quality — does not mean a decline in the spectacular. Take a look at the Premier League’s latest goal of the month compilation and you will see eye-catching individual goals (Facundo Buonanotte, Jeremy Doku), a long-range curler (Josko Gvardiol), a wonderful piece of improvisation by Raul Jimenez to set up Andreas Pereira for Fulham and a perfect Chelsea counter-attack, started by Palmer and rounded off by Nicolas Jackson. All it lacks is a mid-2000s landfill indie soundtrack.

The idea might persist that players were given a degree of creative licence that is not present today, but take the time to revisit almost any Premier League game from that era — a whole match rather than the highlights — and you will be reminded it was far from a golden age for creativity. Wingers were expected to stay wide and full-backs to think very carefully before joining them on the overlap.

There were a lot of crosses, but even more than that, there were a lot of balls lumped forward so that a centre-forward could battle with a central defender and a team-mate could get forward to try to pick up the scraps.

(James Gill – Danehouse/Getty Images)

Guardiola observed with a certain distaste in 2016, after a few months in the Premier League, that “Here you have to control the second balls; without that, you cannot survive”. “The football is more unpredictable here,” he said, “because the ball is in the air more than on the floor.”

Eight years on, Guardiola’s influence has spread and the ball is on the floor a lot more than in the past. English football has become more technical and a lot more measured.

The problem is that, going by what Guardiola said back then, it must have become more predictable as a consequence.

When asked by The Athletic in 2022 to outline what made the Premier League, in his opinion, “the most compelling and competitive” in world football, the league’s former chief executive Richard Scudamore cited the feeling that “on any given day, any team can have a go and take points off somebody else”.

But the wider the financial divide between the richest clubs and the rest has grown, the more scarce such results have become.

Since the start of the 2003-04 season, the ‘Big Six’ of Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham have accounted for 80 out of 84 top-four finishes. For all the justifiable excitement about the emergence of Aston Villa, Brighton and Newcastle over the past few seasons — and by the turmoil at Chelsea and Manchester United in particular — the league is still dominated to an unhealthy degree by six clubs with far greater financial resources than the rest.

Competitive balance is a huge issue across European football, amid growing financial disparity both within and between leagues. The nostalgic view is that this reflects a decline in standards — and in many leagues, which have suffered a drain of talent towards the Premier League in particular, declining results on the European stage suggest that is indeed the case.

The Premier League suffered a few reality checks on the European front last season, but quality is the least of its issues. If anything, the concern in recent years — not necessarily this season — has been that the best teams, Manchester City in particular, have been so strong that jeopardy and competitive balance has gone.

Man City celebrate a fourth consecutive Premier League title in May (Michael Regan/Getty Images)

Not that some will ever see it that way. When one or two teams are streets ahead of the rest, it is deemed to be because standards across the league are so poor. And then when the top teams show vulnerability, as Manchester City and Arsenal have done in recent weeks, it is because standards are so poor. It is as if people pine for the golden age of the mid-2000s when Liverpool came fourth with 16 wins from 38 games and then Everton finished fourth a year later, scoring just 45 goals and conceding 46.

It was ever thus, this reluctance to laud the contemporary. “We had it in Manchester United in the 1990s,” Phil Neville says. “People said, ‘George Best, Dennis Law and Bobby Charlton, they played proper football on bad pitches. You lot are playing on perfect pitches.’

“Time moves on. I don’t like comparisons, but I think football nowadays is probably technically and tactically better than it was in my era. The intensity and competitiveness of the game, I think was probably better back when I was playing.”

That sounds about right, just as the same observation would have sounded right had it been made in the 2000s, comparing that era to the 1980s — or in the 1980s, harking back to the 1960s and an age when the superstars of world sport, from Muhammad Ali to George Best, seemed at once both so other-worldly and so real as their exploits were beamed into households via the magic of television.

Sporting excellence is taken for granted these days. And as that direction of travel continues, the danger, not just for the Premier League but for the game as a whole, is that it becomes too technical, too refined, too perfect. (The doomed pursuit of perfect refereeing decisions, of minutes spent poring over screens trying to calculate marginal offside calls, is part of the same equation — in this case undesirable because perfection is utterly unattainable and anything less now feels unacceptable.)

What is intriguing is seeing that slight drop this season in the number of passes, a slight increase in the number of tackles and fouls… even the sight of Guardiola and Mikel Arteta packing their teams with six-footers.

Is it the beginning of a #barclaysmen revival nobody saw coming? If it is, people should temper their reservations accordingly. Nostalgia, as the baseball philosopher Yogi Berra famously said, ain’t what it used to be.

(Additional reporting: Paul Tenorio, Duncan Alexander)

(Photos: Getty Images/Design: Dan Goldfarb)

Read the full article here