In the eye of the storm, a nightmare unfolding before his eyes, Rob Edwards acted on instinct. He found himself running onto the pitch to be closer to his captain Tom Lockyer, who had collapsed and was lying there, stricken, on the turf.

Then he found himself urging the rest of his players to move away from the distressing scene and give the doctors the space they needed to treat a life-threatening situation.

Lockyer had a heart scare during the Championship play-off final at Wembley in May. “But I knew this time was different,” Edwards says, recalling the trauma during Luton Town’s Premier League match at Bournemouth in December, when his captain suffered a cardiac arrest.

“As soon as I ran on, you could see,” the Luton manager says. “I don’t want to talk about it too much, but it was different. It was so so scary. The play-off final was different because he was very quickly awake, talking, and he was emotional at the time, probably a little bit confused. But clearly, this time, it was a cardiac arrest. He wasn’t responding.”

What was going through Edwards’ mind? “You just go into… football doesn’t matter all,” he says. “I turn around and I see (Lockyer’s partner) Taylor — who was pregnant, bless her — on the sideline. His dad is there. It was silent, the whole ground.”

Tom Lockyer receives medical treatment at Bournemouth (Mike Hewitt/Getty Images)

Lockyer’s heart stopped for two minutes. Issa Kabore sank to his knees to pray for him. The rest of Luton’s players stood there in a state of shock and terror, looking to their manager for guidance. Edwards addressed them there and then on the pitch as the two teams’ medical staff, along with paramedics, performed their heroics. Then he led his players to the sanctuary of the dressing room, where, away from the eyes of the world, he burst into tears.

“I kind of broke down in front of the lads,” Edwards says. “I said, ‘I’m supposed to be a leader here, but I don’t know what to say. I can’t lead you right now at the moment’.

“But then there were some voices within the group. Everyone acted differently. (Forward) Carlton Morris spoke up and some members of the staff did as well. And that’s where you can see how strong we are as a unit — players and staff. I know I have to stand up and be the face of it most of the time, but that just showed our strength and our togetherness because I wasn’t in a position at that time to carry on.”

Edwards’ feelings of helplessness were laid bare when, after the match was abandoned, he and his players walked around the pitch applauding both sets of fans to thank them for their understanding. His eyes reddened and watered as he struggled to hold back the tears.

But where Edwards felt powerless, many of us saw strength: the strength first to show leadership and then to show the vulnerability anyone would have felt in that situation. We saw humanity, empathy, authenticity and a depth of emotional investment that is based on people, lives and community, rather than just a results business.

By the time Edwards reached the Royal Bournemouth Hospital that evening, Lockyer’s condition was stable and his family were at his bedside. “And he was up and talking, which was incredible,” the manager says.

Edwards left the hospital feeling drained but relieved and proud at the way so many people at the Vitality Stadium that day — the two clubs’ medical staff, players and supporters and indeed the match officials — had come together. What emerged from a life-threatening situation, “the scariest moment I’ve ever had in my life”, was life-affirming.

Two months on, Lockyer has been back to The Brache, Luton’s training ground, and has made an emotional return to Kenilworth Road, sitting just behind the bench for last weekend’s 3-1 defeat by Sheffield United.

Tom Lockyer acknowledges fans before Luton’s game with Brighton (Clive Mason/Getty Images)

The defender, 29, has had an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) fitted to detect and stop an irregular heartbeat. No decision has yet been made on his future. “There’s no pressure from us,” Edwards says. “He’s got a baby on the way very soon. That’s the primary concern now for him and Taylor. That’s all I want them to focus on. After that, there will be a rehabilitation and that’s as far as I want to go or say at the moment. I’m sure he’s got his own ideas. It’s just about being fit for everyday life at the moment.”

Lockyer has continued to play a part in Luton’s battle to avoid relegation, something Edwards was eager to embrace when he held his first training ground meeting with his players after the captain’s collapse at Bournemouth.

“It was emotional,” the manager says. “I needed to speak about Tom. We wanted to try to embody him. At every team meeting and every game, we’ve got Locks’ shirt and captain’s armband there. He’s a really special person. He’s one of those who has got his own unique journey. To go from the National League (with Bristol Rovers) to the Premier League is incredible. We talked about that a lot. I wanted us to embody his journey and everything he is as a man and person. We’ve talked about that a lot.”

On a wall inside Luton’s performance centre, which houses their gym and cryotherapy chamber, there is a message that lays out “expectations”. It lists the qualities required of players “in great teams”: accountability, unselfishness, communication, hard work, discipline, loyalty and a willingness to put the needs of the collective above those of the individual.

You see such messaging on the walls of every training ground up and down the country. In some cases, it seems laughably hollow. But not at Luton. Their rise from the National League to the Premier League in a decade, which saw them promoted under John Still, Nathan Jones, Mick Harford and finally Edwards, has been a powerful, inspirational story of unity and defiance.

Luton is an unglamorous, hard-edged, working-class town, its economy hit hard by the decline of both the hat-making trade and, much later, British car manufacturing. Geographically it lies just beyond the Home Counties, sometimes described as London’s “stockbroker belt”. Socially and economically, it faces challenges many of its surrounding towns do not.

For a long time, its football club was a useful symbol of the town’s struggles: from punching above its weight in the 1980s, even beating Arsenal in the final of the League Cup in 1988, to relegation from the top tier in 1992, missing out on the Premier League gravy train, falling into administration three times in a decade and dropping out of the Football League altogether in 2009 amid fierce resentment towards previous owners and the game’s authorities.

The story of Luton’s revival merits more than a brief tangent in an interview with their manager. It was told in depth here but at its heart, it reflects those values laid out on the wall by Edwards and his staff: hard work, loyalty, the intense commitment of the individual to the collective.

Lockyer has always manifested those qualities, but in a team without ego, he is not alone. Their underdog story is personified by 29-year-old midfielder Pelly Ruddock Mpanzu, who was here in the National League days when Luton were training “in a taped-off park next to some Portakabins with people walking their dogs about”; by Alfie Doughty, who was a bit-part player at Stoke City and Cardiff City two seasons ago; by Morris, who spent 15 years at Norwich City, from the age of 10 to 25, and had a single first-team appearance to show for it but is now a Premier League centre-forward at the age of 28; by Elijah Adebayo, who, four and a half years after being released by Fulham, was among the nominees for the Premier League player-of-the-month award for January.

Luton’s team spirit has been a feature of their season (Matt McNulty/Getty Images)

Edwards is asked what he sees first when he looks at his team: the collective success story or the individual stories at the heart of it. “I can see all of that,” he says. “I can see us improving as a team, I can see us building understanding, cohesion and confidence as a team and I can see some outstanding individual performances: players who were perceived as ‘Championship footballers’ performing in the Premier League, being nominated for player of the month or whatever.

“I can see the growth in them. My job is to try and help to develop people. I’m not one of those people who’s going to say, ‘That’s down to me’. Hopefully, what we can do is create an environment where the players feel they can go and best the best they can be. We’ve improved individuals, but hopefully that then improves the collective.”

Approaching his 30th birthday, with 33 England caps, several big contracts and a bright future behind him, Ross Barkley seemed an unlikely candidate to join Luton last summer. After unfulfilling spells at Chelsea and at Nice, on the French Riviera, did he have the appetite for a survival mission at Luton?

The big question, dating back to his early years at Everton, was all about whether Barkley had the work ethic to make the most of his talent. He has often been dismissed as a luxury player in an age when, increasingly, out-of-possession work is integral. To thrive in the Premier League again at the age of 30 — and with Luton, of all teams — seemed like it would require a change of mindset as well as a change of role.

The answer has been emphatic. “Ross has been amazing,” Edwards says. “He’s hungry. He’s got a point to prove — not to us, but maybe he’s got a bit of unfinished business. We’ve given him a home. We’ve given him support. We’ve given him a platform.

“I can’t make Ross Barkley better. But together, we can. What he’s shown this season is another side to his game. He’s tracking runners, winning the ball back. He’s showing even more responsibility than he would have done in previous years and he’s affecting us going forward and with the ball as well.

Ross Barkley has been revitalised at Luton (George Wood/Getty Images)

“We want him to drive forward. We want to get him in the box. I don’t want to rein him in. But if you play for Luton and you play for me, you’ve got to run. And he’s doing that really well. I love working with him. He’s a brilliant guy and super talented as well.”

Far from a luxury, Barkley is regarded as a leader at Luton, excelling in a deeper midfield role to the extent that a recall to the England squad does not seem beyond the realms of possibility.

“Ross loves playing football,” Edwards says. “And of course, it has to be structured and adhere to what we do, but he loves playing football. You should see the demands he puts on people out there. After training today, he was doing some more running. Then he came over to join with some finishing practice that Trolls (assistant manager Paul Trollope) was doing with the forwards — and Ross is demanding of people and he’s driving them. He’s an amazing person who loves football and works hard.

“He’s had a couple of difficult years and I suppose people formed an opinion on him. That’s just what happens. At this level, people are going to form an opinion of you. But along with us as a football club, he’s changing people’s minds again.”

Edwards is loving the Premier League experience. It has come about far quicker than he imagined when he took the Forest Green Rovers job less than three years ago — let alone when he was sacked by Watford in the opening months of last season — but it is what he hoped for when he began his coaching journey a decade ago.

He says “not too much” has surprised him from a tactical viewpoint. The surprise has come, at times, with the quality of the opponents. He cites the way an excellent performance at home to Wolverhampton Wanderers last September was undone by one lapse that was ruthlessly, wonderfully exploited by Pedro Neto. “Every team has got a Neto that can hurt you with one brilliant moment,” he says. “The top teams have got four or five of them…”

The big shock has been the intensity of the media glare — even if in Luton’s case it has increasingly been favourable rather than hostile. He had brief experiences of the Premier League as a player at Aston Villa and Blackpool, but it was nothing like it is now in the social-media age.

One thing he wasn’t prepared for was one of his post-match interviews to go viral, watched by 15.8millions users on X, formerly known as Twitter, as he unwittingly attracted a new army of admirers. Some of them asked, “Who is this football manager?” and others declared him to be “the type of man you save you before your kids in a fire”. One user said, “Get this man out of the relegation zone immediately. A face like that doesn’t deserve this.”

get this man out of the relegation zone immediately… a face like that doesn’t deserve this https://t.co/YUKuiSOFRX pic.twitter.com/HXFijA6fuh

— bri bri (@wonsojus) January 17, 2024

Edwards squirms at the mention of it, saying he found it “embarrassing” and “a bit weird”. His wife laughed it off, but his teenage daughters hated it. His son, who is far more impressed by Erling Haaland, was non-plussed.

The spotlight on a Premier League manager can be fierce and unforgiving — and yes, sometimes “a bit weird”, even if few of Edwards’ peers can relate to his social media popularity.

But this, managing in the Premier League, is what he has been working towards. “I love the pressure of it,” he says. “I love coming up against the best, competing against the best, and I think the players do too. The next three fixtures: Manchester United, Liverpool, Manchester City (in the FA Cup). We know those three clubs are giants and we’re viewed differently, as minnows, but we go into every game trying to win and believing we can win. That is our attitude.”

No sooner had Luton won promotion through the play-offs last May, beating Coventry City in a nerve-shredding penalty shootout, bookmakers announced they were short odds-on to go straight back down again. Pundits lined up to write off a club whose stadium, budget and playing squad had appeared meagre by Championship standards never mind Premier League.

“I understand why everyone wrote us off,” Edwards says. “We’re probably the smallest club to have played in the Premier League. If not, then one of Blackpool, Huddersfield and a few others you could name — and I was part of that Blackpool team. I get it. I wasn’t offended. But I was offended by the way people said it. I thought some people were disrespectful.”

Luton lost their first four games in the Premier League. It was worrying — and this was arguably having exceeded the expectations of most and won praise, sometimes of a back-handed nature, by competing at stages in each game.

Edwards was more concerned than he admitted publicly at the time. “The first couple of games, we just didn’t run hard enough, which is unlike us because that’s a really big part of the success we had last year,” he says. “Some of our sprint recoveries, the basics, we didn’t get right. The Chelsea goals (when they beat Luton 3-0 at Stamford Bridge in August) still haunt me. We got some really basic things wrong. We didn’t run hard enough. If you don’t do that at this level, you’ve got no chance.”

There was a change of system after that, switching from 3-5-2 to something more akin to 3-4-3 or 5-4-1. But rather than the positions on a chalkboard, it was a change of mindset: less respectful and less deferential to their opponents. “It wasn’t about changing our principles or changing the way I coach or anything like that,” Edwards says, “but we had to get back to basics and try to be more difficult to beat.”

Rob Edwards issues instructions at Everton (Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

An upturn followed. “We were in games, difficult to beat, and we were taking the odd point here and there,” Edwards says. “We won at Everton, got a good away point at Nottingham Forest, then we only lost 1-0 to Manchester United, drew with Liverpool. But it wasn’t necessarily a reflection of me or how I see us. And then Brentford away in early December, we really didn’t like that performance. We were a bit passive. Other games, even when we lost 4-1 at Brighton, we were trying to do the right things. At Brentford, I didn’t like us. We were off it.”

It is why, Edwards and his staff decided they had to change things again.

“I just thought, ‘Right, this is what I want us to be and this is what suits the players as well’,” he says. “The Arsenal game (a 4-3 defeat, with Declan Rice scoring Arsenal’s winner in stoppage time) was a bit of a coming of age for us. Some people might think, ‘I’m not sure you can do that’. (But) if we’re going to go down, we’re going to go down in a certain way.”

From the moment he went into coaching, shadowing his former Wales team-mate Gareth Taylor at Manchester City’s academy, working with Wolves’ under-18s and then with the first team under Paul Lambert before going on to manage his hometown club Telford United in the National League North and returning to Wolves to coach their under-23s, Edwards was regarded as a progressive type in his approach to both management and coaching.

That growing reputation earned him a job as England’s under-16s coach and a specialist “in-possession” coach with the under-20s team, working under Keith Downing. He worked with Phil Foden, Conor Gallagher, Tariq Lamptey, Angel Gomes and Emile Smith Rowe. He left the FA in June 2021 to become head coach of Forest Green, whom he promptly led to promotion from League Two, winning plaudits for their football.

The breadth and depth of his experience as a player and a coach is rare for a 41-year-old in English football. He uses the word “eclectic”. He feels he learned “decent empathy” through his up-and-down experiences as a player with Villa, Wolves, Blackpool, Barnsley, Wales and others before being forced to retire at the age of 30. He has learned much from his various coaching roles — including that predictably brief, brutal experience down the road at Watford.

“I’ll have some non-negotiables,” he says. “I want us to press, I want to attack quickly. I want control, but I don’t want it just for control’s sake. There’s got to be a purpose with our play. So if you ask, I love how Liverpool play, I love how Tottenham play, I love how Newcastle play. I’m completely mesmerised by Manchester City, who are amazing but different with the complete control they have.”

It is fascinating to hear him say the way Luton performed in their first few months in the Premier League was not “a reflection of me or how I see us” — to talk of a change of approach mid-stream, something that Barkley spoke about recently when he spoke of a “different direction” and trying “to pass out from the back and build forward instead of being direct constantly. We’re mixing it up and that’s what is maybe surprising teams now”.

It has. After that disappointing Brentford defeat, Luton lost their next two games, against Arsenal and Manchester City, but then came a run of five wins, three draws and just one defeat in the next nine matches in all competitions. They stunned Brighton, beating them 4-0, and earned a 4-4 draw at Newcastle United. Last weekend brought the jolt of a 3-1 loss to Sheffield United, but the overall trend is positive. They are having far more possession and creating far more chances than in the first part of the season.

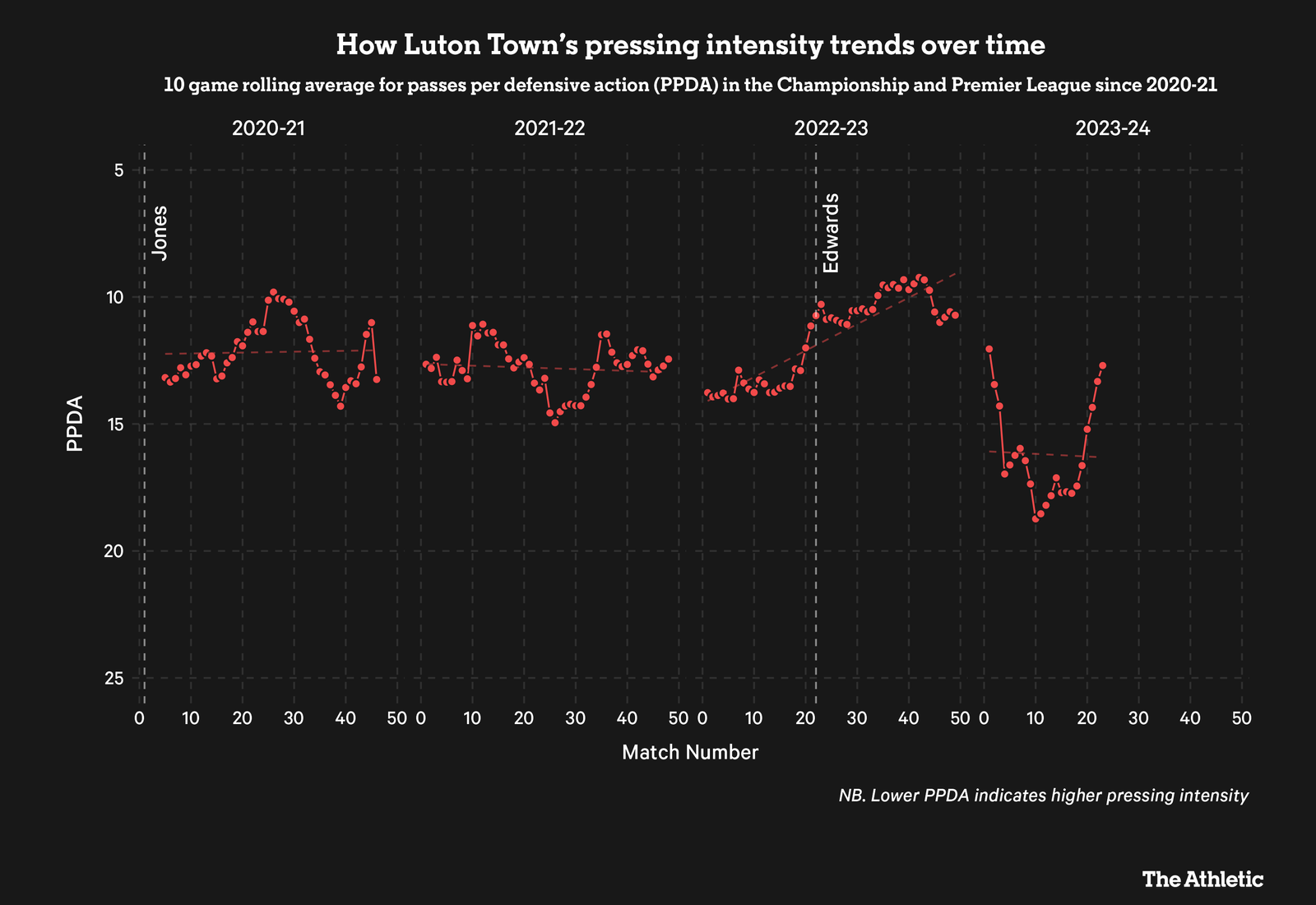

The biggest change is in their pressing, which can be measured by ‘passes per defensive action’, or PPDA, a metric that shows how many passes a team allow the opponents to make before trying to win the ball back with a defensive action, such as a tackle, interception or clearance.

For context, PPDA in this season’s Premier League ranges from Liverpool’s 9.1 (the most intense) to Nottingham Forest’s 18 (the least intense). For that game at Brentford in December, Luton’s PPDA was 29.2, hence Edwards calling their performance “passive”. Their average over their last six Premier League matches is just 9.2, which is the other extreme.

“We’ve been able to evolve and change,” Edwards says. “We’re not just a sort of plucky team now. We’ve been very brave in the press, doing some unique things in our pressing that no one else does. But no one picks up on that’s fine.”

Such as? “Some incredibly brave things that are risky, that people maybe will start to pick up in another 10 games or so,” he laughs. “What it has done is given us the opportunity to have more of the ball. We’ve been able to get more control in games. We’ve become more of a threat because we’re winning the ball back higher and we’re actually defending low less of the time. In all departments really, it suits us.

“It’s risky but it’s also entertaining and it gives us a better chance of winning. We want to entertain. We want to try and be good to watch. I don’t want to be known as a defensive coach. I know we’ve got to defend, I know it’s a big part of the game and we have to accept that when we’re coming up against top teams we’re going to have the ball less, but I’m not going to accept just waiting to be killed. We’ve got good players, athletic players, players who are aware tactically and understand what we’re doing, so let’s go for it.

“It suits as a football club as well. It really does. Yes, there’s a risk, but the reward is greater than the risk.”

The Premier League table has Luton in 17th, one point and one place above the relegation zone. But Edwards refuses to see it that way. “We’re in the bottom three and we’re a point behind Forest,” he says. “That’s how I see it.”

In Edwards’ mind, Everton are nine points clear of Luton, not one point behind. The Merseyside club are awaiting the verdict of their appeal against a 10-point deduction for breaching financial regulations. For the deduction to be quashed completely seems unlikely, given that the Premier League argued for an even heavier sanction, but that is the outcome Edwards and his staff at Luton are prepared for.

“I keep getting the analyst to update the table (with Everton’s 10 points restored),” he says. “I don’t want to show the players all the time because I don’t want to flatten them, but we have used it and said, ‘This is the table’. We’re in the bottom three and we’re one point behind Forest, under that dotted line, and we need to try to get out of it.”

How does he feel about being in a survival battle with clubs who, in stark contrast to Luton’s adherence to the measured approach that has earned them four promotions in a decade, have spent wildly in the hope of retaining top-flight status? (Forest, as well as Everton, have been charged with breaching financial regulations.) “We can’t rely on those things,” he says. “It’s not something we can control.”

There is an obvious contrast to be drawn with Everton’s and Forest’s spending under the ownership of Farhad Moshiri and Evangelos Marinakis, but for Luton, the more relevant comparison is with Burnley and Sheffield United, who were promoted ahead of them last season and spent far more heavily last summer but have found Premier League points much harder to come by.

“I remember saying at Wembley (after the play-off final) that we were going to do it sensibly,” Edwards says. “It’s hard to doubt what Gary Sweet (the chief executive), the club, the board and the recruitment team have done over the last decade. Their body of work has shown that you can have success coming through the leagues.

“Money, of course, matters, and I know you can marry up budgets with where teams finish in the league. I get that. But we bucked the trend big-time in the Championship. It’s hard to do that in the Premier League, but we’re showing with our performances that we’re giving it a really good go.”

They are. They have surpassed expectations to such a degree that former Liverpool defender Jamie Carragher proposed in his latest Daily Telegraph column that Edwards will be a strong candidate for any manager of the year award. Luton, he wrote, “began the season looking like they might be an embarrassment to the Championship they came from. Instead, they have been a credit to their manager and English football”.

In his first two seasons managing at professional level, Edwards led Forest Green and Luton to promotion. “This (staying up) would be bigger,” he says without hesitation. “It was an amazing achievement last year to do what we did — and what Nathan Jones and the recruitment team had done before we arrived because it was all set up and ready. Promotion was something we will treasure forever, but we want more.

“I said at the start of the season it’s like a different sport at this level. At times, it really is, with what we’re going up against, the quality of the players. It’s so different. If we can do it, I would see it as a bigger achievement than getting up in the first place.

“I want us to survive. I don’t want it to be because of deductions. I don’t want people to throw that at us. Our target is to get to 40 points. I know it’s a big aim, a bold aim, but we have to.”

(Top image: Oliver Kay)

Read the full article here