And so another season ends with another day of reckoning in the Premier League, with the title race still alive on the final day.

The trophy will be dispatched to Manchester, adorned in the now-familiar sky-blue ribbons, but a replica will be sent to north London, complete with red ribbons, just in case a dramatic late twist sees Arsenal crowned champions for the first time in 20 years.

It is a fascinating prospect for neutrals, never mind those of an Arsenal persuasion. But realistically, we all know how this ends:

The City success story has become… complicated.

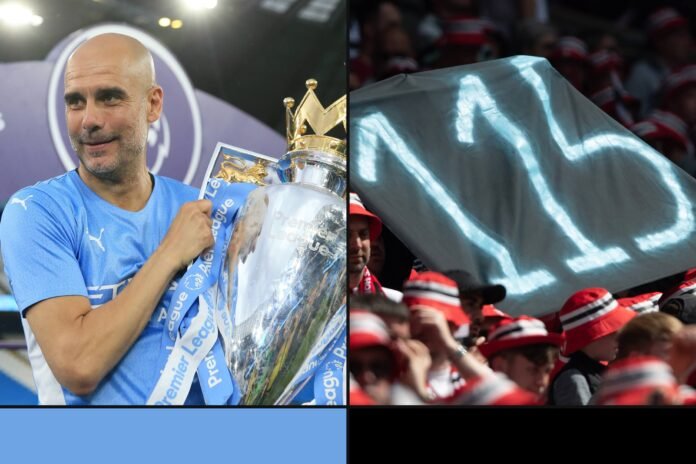

How could it not be complicated when Sheikh Mansour’s ownership of the club has been described by Amnesty International as “one of football’s most brazen attempts to ‘sportswash’ a country’s (the United Arab Emirates’) deeply tarnished image through the glamour of the game”? How could it not be when the Premier League has referred City to an independent regulatory commission over 115 alleged breaches of its financial regulations over a period spanning nine seasons?

Over the nine years under investigation, City won three Premier League titles.

They won a fourth, fifth and sixth in the four years it took between the Premier League launching an investigation into the matter (first raised by the German magazine Der Spiegel in 2018) and, after overcoming a series of legal hurdles, referring it to a regulatory commission.

They won a seventh last season, three months after the charges were brought against them.

They are overwhelming favourites to win an eighth before the as-yet-unspecified point at which Masters insists a regulatory commission will finally hear the case.

And it is such an enormously complicated case — not as straightforward as Everton’s and Nottingham Forest’s PSR breaches, as much as some might like to equate them — that few people would be surprised if City win a ninth league title before the whole thing is resolved one way or the other.

All of this is damaging for the Premier League brand. How could it not be when its dominant club of this era has had these allegations hanging over them for so long? Whether your view is sympathetic or hostile to City, what does this situation say about the Premier League and — a hot topic these days — its ability to regulate its clubs and its competition?

It is also damaging for City. Their chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak admitted as much last June, saying that the way the club has been “characterised”, over the initial allegations and the subsequent charges, “is very frustrating because it takes so much from the great work that’s happening at this club”.

It does. Without question, praise for City’s achievements is tempered by the allegations that have hung over the club for so long.

There is always that caveat, the accusation that none of this — this phenomenal group of players, under this phenomenal coach, hired by a phenomenal sporting operation — would be possible without rules being broken along the way.

City have disputed the context of the emails published in Der Spiegel, but not their veracity. Above all, they have challenged the legitimacy of the case against them, claiming the club has faced an “organised and clear attempt to damage (its) reputation”.

The club’s reputation has been damaged without question. Even when they successfully overturned a two-season ban from UEFA competition in 2020, the verdict from the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) did not make pleasant reading.

Some of the charges against City were not established, but others were merely time-barred. The contents of the controversial emails were not disputed. They were accused of a “blatant disregard” for UEFA’s investigation, found guilty of not cooperating with UEFA by failing to provide substantial amounts of evidence and fined £8.8million ($10.1m).

They did not prove, as Guardiola claimed last year, that “we were completely innocent”.

Guardiola on the touchline at Tottenham on Tuesday (Justin Setterfield/Getty Images)

But should that affect anyone’s view of the team? Is it possible to differentiate the ownership, the management at executive level and the football team? Is it possible to have serious concerns about a) sportswashing and the growing phenomenon of football clubs used as geopolitical tools, and b) the alleged financial breaches, while also holding a deep admiration for Guardiola and a group of players who have scaled such extraordinary heights over the past seven seasons?

When you make such a suggestion, you tend to annoy pretty much everyone.

Question the club’s financial arrangements, or whether it is healthy for a club to be owned by the UAE’s vice-president, and you find yourself accused of an agenda against the club or even against the Middle East. Hail City’s brilliance and you are accused of being a shill for their owners. Do both — even at the same time — and the flak comes from both sides.

But how can you not admire Guardiola and a group of players who, over the past seven seasons, have reached levels of consistency and brilliance arguably unmatched in English football history?

It’s not just the number of league titles. It’s the number of goals, the number of wins, the number of points — and in an era when, thanks to its unrivalled commercial and financial strength, the Premier League has finally lived up to its long-beyond claim to become the strongest in Europe.

Ruben Dias and Kevin De Bruyne hoist the Premier League and Champions League trophies last June (Oli Scarff/AFP via Getty Images)

And beyond the pure numbers, it’s the technical brilliance and ingenuity of their football.

There have been many wonderfully accomplished players and teams in the Premier League, but never before was there such technical sophistication from back to front. Until Guardiola arrived on these shores in 2016, and certainly for his first season here, there was a widely held belief that his dogmatic belief in pure possession football was untenable amid the blood and thunder of English football.

A personal view, for what it’s worth: those first two title-winning seasons under Guardiola were a purer, more entertaining, more enthralling, more admirable team than the latest model, built around the focal point of Erling Haaland, a more physical midfield and with repurposed central defenders where the full-backs used to be. They were more formidable in the Premier League, even if success on the Champions League stage proved elusive.

In the 2017-18 and 2018-19 seasons, they won 32 matches, finishing with 100 and 98 points respectively. Last season they won it with 28 wins and 89 points. This season can end with a maximum of 28 wins and 91 points. Despite the presence of Haaland, they have scored fewer goals than in 2017-18, too. The free-flowing football of those first two title-winning campaigns has given way to something more controlled and less… electrifying.

But they are still brilliant, still formidable, still remarkably focused and consistent — and have been so, give or take the occasional dip, for seven seasons as the team has evolved.

Ederson, Kyle Walker, John Stones, Bernardo Silva and Kevin De Bruyne (and Phil Foden, albeit on the margins for the first few years) have been there throughout. Rodri and others have excelled since joining the party more recently. For all their technical excellence, their most underrated quality, as a collective, is their resilience.

Haaland has become City’s focal point (Marc Atkins/Getty Images)

If — if — the club ends up found guilty and punished for accounting offences, whether it is a handful of them or all 115, it will of course cast a great shadow over this golden era.

But this is not, as some would have it, a Lance Armstrong scenario.

In cycling, an individual sport where success correlates directly to the power output and endurance of the guy on the bike, Armstrong was found to have knowingly pumped his body full of EPO and human growth hormone as part of what the United States Anti-Doping Agency called “the most sophisticated, professionalised and successful doping program that sport has ever seen”.

That is very different to being accused of breaching financial regulations and failing to cooperate with an investigation. If there are parallels, they don’t go very far.

One is the most brazen act of cheating imaginable in sport. The other is about whether a club supplied accurate financial information in a sport that had previously existed without spending limits.

Any club found guilty of breaching those financial regulations should be punished accordingly, as Everton and Forest have been. The accusations against City are far more serious and far more numerous. But it is hard to get too moralistic about it. Even in the worst case, there would be an almighty difference between what Arsene Wenger used to call “financial doping” and, well, actual doping.

And although this is another question entirely, City fans are entitled to question why spending regulations suddenly became a preoccupation for England’s and Europe’s dominant clubs in the late 2000s. It doesn’t affect the rights or wrongs of their case, but it does serve as a reminder that the principles of Financial Fair Play were not exactly carved on tablets of stone.

There might be a temptation to say that all of this money made success inevitable for City, but Guardiola was correct to point out this week that Manchester United and Chelsea have spent similar sums in recent years and “they are not there”. In fact, they are barely halfway there.

In other words, money alone does not account for City’s sustained excellence. That money has built a top-class football operation (which it has belatedly occurred to the Manchester United hierarchy to try to replicate). It is an environment in which Guardiola feels he has all the conditions to succeed and in which he has helped so many players — and rarely the A-list “superstar” signings favoured at Old Trafford over the past decade — take their game to another level entirely.

The emails published by Der Spiegel suggest a certain brazenness at work at City in the early 2010s and many of the charges relate to questions of whether the club acted in “the utmost good faith”. But nobody is accusing Guardiola or his players of acting in bad faith. These are questions for men in suits. Why should they affect the way we regard the men — and indeed the women — in boots?

Crestfallen United players applaud their fans as City celebrate winning the derby in March (Simon Stacpoole/Offside/Offside via Getty Images)

Of course, it is unlikely Guardiola would even have given City a second glance had the club not been built up so impressively during the years when their accounts are under investigation. And as impressive and hard-working as the people working in the commercial department might be, the very nature of the charges hanging over City means there was a natural tendency to say “Yeah, but…” when the club announced last June that they had surpassed Real Madrid as the most valuable brand in the sport.

But the Champions League victory that came in Istanbul a few days earlier was so much easier to laud. Surely it is possible to admire and praise a team — a genius of a coach and a group of players whose talent is matched by their application — while questioning the institution? Or to put it the other way: surely it is possible to question an institution while admiring and praising a team?

Even as another judgment day awaits in the Premier League this Sunday, everyone knows the real day of reckoning for Manchester City lies in the middle distance. That — the sportswashing accusations, the allegations in Der Spiegel, the 115 charges — is the prism through which the growth of a modern-day sporting empire is inevitably seen.

But the team? It’s a brilliant team that deserves nothing but praise. It’s a tale of two Citys, a City of two tales. It should be perfectly natural to acknowledge both.

(Top photos: Getty Images)

Read the full article here