The Athletic has decided on the 35th anniversary of Hillsborough to re-publish an article that was originally released two years ago, which details the horror of the day, as well as the impact on some of the survivors.

When Martin Roberts returned to Halifax on the night of April 15, 1989, he wet the bed as he tried to sleep. The next morning, he did not say a word to either of his parents, his sister or his brother about what he had witnessed the day before in Sheffield, where 97 Liverpool supporters lost their lives in a steel pen he somehow escaped from.

Martin spent Sunday walking around the garden for hours, hopelessly trying to make sense of it all. By Tuesday morning, he was working again, at Barclays bank. His boss called him into a side room and asked how he was feeling. A stupid question. Martin wondered what his colleagues were thinking, fearing they believed what had been written in the papers about fans like him.

Martin’s deepest scars from Hillsborough were not physical but mental. His father, Liverpool-born, possessed old-school values. His generation understood broken arms and broken legs, but Martin’s pain was not visible. This contributed to him throwing himself into his career and back into what seemed like a normal life. He thought he was coping. Martin got married and became a father to two kids. But Hillsborough was always there. When it was not staring him in the face, it was nestling somewhere in his mind, eating away at his soul. There were anniversaries, so many anniversaries. There were inquiries and inquests. Yet the torment of Hillsborough did not mean as much to Halifax, a town an hour up the motorway from Liverpool, as it did to Martin. Quietly, he was suffering. It felt like he was living in a world he could not relate to. In 2017, his wife was diagnosed with a tumour. Meanwhile, his dad had cancer and his mum had died three years prior after suffering from dementia. The sense of loss and fear was enormous, multiplied because the memory of Hillsborough was still there, waiting to be unleashed into the forefront of his thoughts. He thought he could cope.

Again, he threw himself into work, sometimes doing 14 hours a day. He did not want to be around his wife in case she could see he was struggling at a time when she needed support. To friends, he started making excuses so that he did not have to socialise with them, sometimes faking illness. He felt like he was telling lies to everyone. Martin was physically and mentally exhausted. The second round of Hillsborough inquests between 2014 and 2016 had forced him to look for help through a psychiatrist after a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Six months of treatment followed, including cognitive behavioural therapy and eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR), a process that forced him to relive the worst moments in his life. This led him to thinking he could smell the vomit of the supporters he’d seen die at Hillsborough. These were images he’d blocked out for 30 years. During those intense experiences, he could feel his body heating up — like he was back in the pen, trying to free himself from the terror by clambering over the limp bodies of women and children. It became too much for him. He concluded that he was a bad husband and a bad father. One night, he went upstairs and imagined his own funeral. Previously, he had contemplated the reaction from his family and friends if he crashed his car into a wall. It felt like it was the right thing to do.

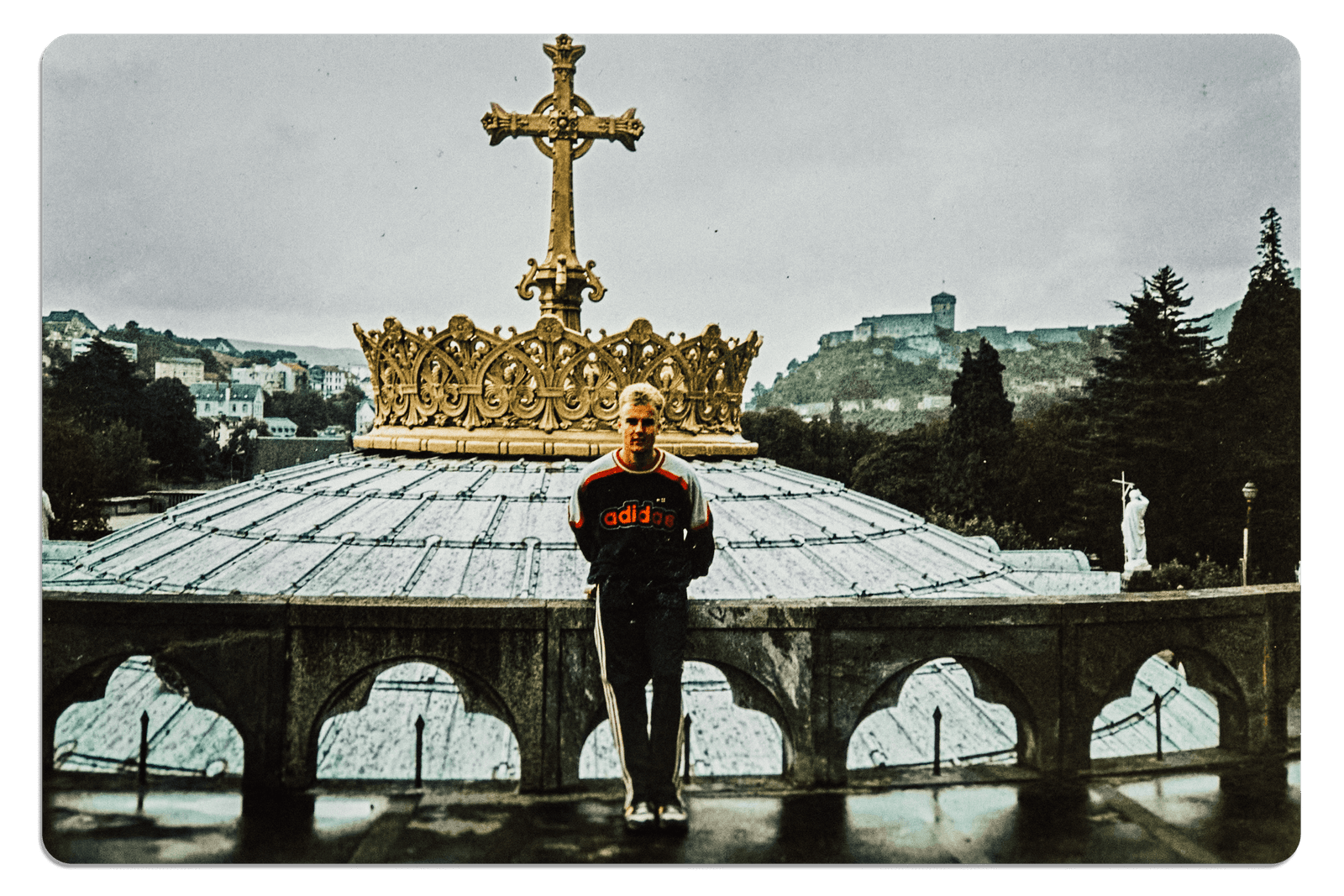

Roberts in his younger days

In bed, beside his wife, he planned where he was going to go and how he was going to kill himself. There was a bridge nearby and, for the first time since Hillsborough, the decision made him feel at peace. Previously, he’d thought of suicide as a selfish act. He was now in a position where he concluded it was the only way out. At 4am, he climbed out of bed and got dressed. He was walking out of the house when his wife came running down the stairs asking where he was going. He told her that he couldn’t take it any more, that he needed to remove himself from both her and the kids. He told her he was done.

The skies are clear, the sun is shining, the waters of the Mersey river glisten and Liverpool’s FA Cup tie with Nottingham Forest is 24 hours away: weather, opponents and a competition that steals the minds of every person sitting around a table in a side room of the Albert Dock’s Tate Gallery, transporting them straight back to the spring day when, as Martin says, “everything changed.” Five other men, each of them aged 30 or under in 1989, nod in agreement. Like Martin, they are survivors of the Hillsborough disaster but the term makes some of them feel uncomfortable.

Another survivor, Philip Wilson, separately suggests it was both the best and the worst day of his life: the best because he did not die, the worst because nothing was the same after that. The nightmares, along with a sense of grief, guilt and anguish, were made worse by the lies and smears of the authorities, who, with the help of some craven sections of the media, falsely pinned the blame on fans. Although Liverpool supporters maintained they knew what really happened at Hillsborough, it would take 27 years for the truth to be clearly defined in a courtroom where a jury was asked to answer 14 questions concerning Hillsborough.

For Paul Dunderdale, whose friend Graham Roberts died in the crush, the answer to question seven was the most significant because it confirmed supporter behaviour did not contribute to the tragedy. It was only then, he thinks, that the wider public started to change their attitude because finally, the truth was carved into the writings of the establishment. The jury also returned an unlawful killing verdict on the deaths, which in 2021 rose to 97 following the passing of Andrew Devine, who lived the last 32 years of his life with horrendous injuries because of crushing. Last summer, the trial of two former South Yorkshire Police officers accused of amending 68 witness statements, along with the force’s former solicitor, was stopped by a judge on a legal technicality.

Given that nobody has seen jail time for Hillsborough, it is understandable why anger remains in Liverpool as well as in other parts of the country. Martin’s presence in Sheffield is a reminder that the disaster should always have been viewed as a national tragedy. For survivors, Hillsborough has led to the collapse of marriages, family break-ups, dependency, violence, job losses and suicide attempts. Some have been successful but Martin lives to tell his story before five men he has never met because he stepped in front of his wife and admitted, “I need help.” Sitting next to Martin is Alan Radford. While Martin wonders whether it might have been better for him had he lived in Liverpool instead of Halifax, Alan wanted to vanish from the city where he grew up because there was no escape from the disaster.  Alan was not in either of the central pens in the Leppings Lane terrace but he’d sold a ticket for that area of the ground in an Anfield pub the night before the semi-final. His daughter was barely a year old in 1989 and she too has had to live nearly her entire life with the consequences of her father’s regret. Alan and his wife Rita argued endlessly after the disaster, which he had seen unfold from the stadium’s main stand. “We weren’t far off getting divorced,” he says. “Neither of us felt lucky. You’d pick the paper up and day after day, we were getting battered. There was no escape from it. I know people who left the city and never came back because of this.”

Alan was not in either of the central pens in the Leppings Lane terrace but he’d sold a ticket for that area of the ground in an Anfield pub the night before the semi-final. His daughter was barely a year old in 1989 and she too has had to live nearly her entire life with the consequences of her father’s regret. Alan and his wife Rita argued endlessly after the disaster, which he had seen unfold from the stadium’s main stand. “We weren’t far off getting divorced,” he says. “Neither of us felt lucky. You’d pick the paper up and day after day, we were getting battered. There was no escape from it. I know people who left the city and never came back because of this.”

Rita worked at Norwich Union in Liverpool’s city centre. In 1992, she was told that she’d be redundant unless she moved to Norfolk. Alan agreed that it was a good idea. “But, I did a lot of bad things down there…” He became a regular at a pub where he was sometimes asked about “the number of people I’d killed at Hillsborough”. One night, he snapped. “I told one of these fellas, ‘I won’t be long…’.” So, he went home and picked up a bat. “And I battered him…” The incident was never reported but Alan did not feel like he’d got away with anything. Hillsborough was still there. In 1997, he attended five funerals in as many months, including his own father’s.

“Carrying coffins all of the time — on top of all this, Hillsborough…” After the last of the funerals, he drove back to Norwich and took sleeping tablets and some painkillers. “I was hoping I didn’t wake up.” But he did. Many years later, there was another attempt on his own life, triggered by the collapse of a trial involving the match commander David Duckenfield. “If I saw the number 96 in a TV advert, it would be enough to send me off,” he says. “Hillsborough’s killed a lot more people than 97, I’m certain of that.” He was living in Warrington when the second round of inquests was held in the town. It drives him crazy that despite there being an “unlawful killing” verdict, nobody has been jailed for their actions at Hillsborough.

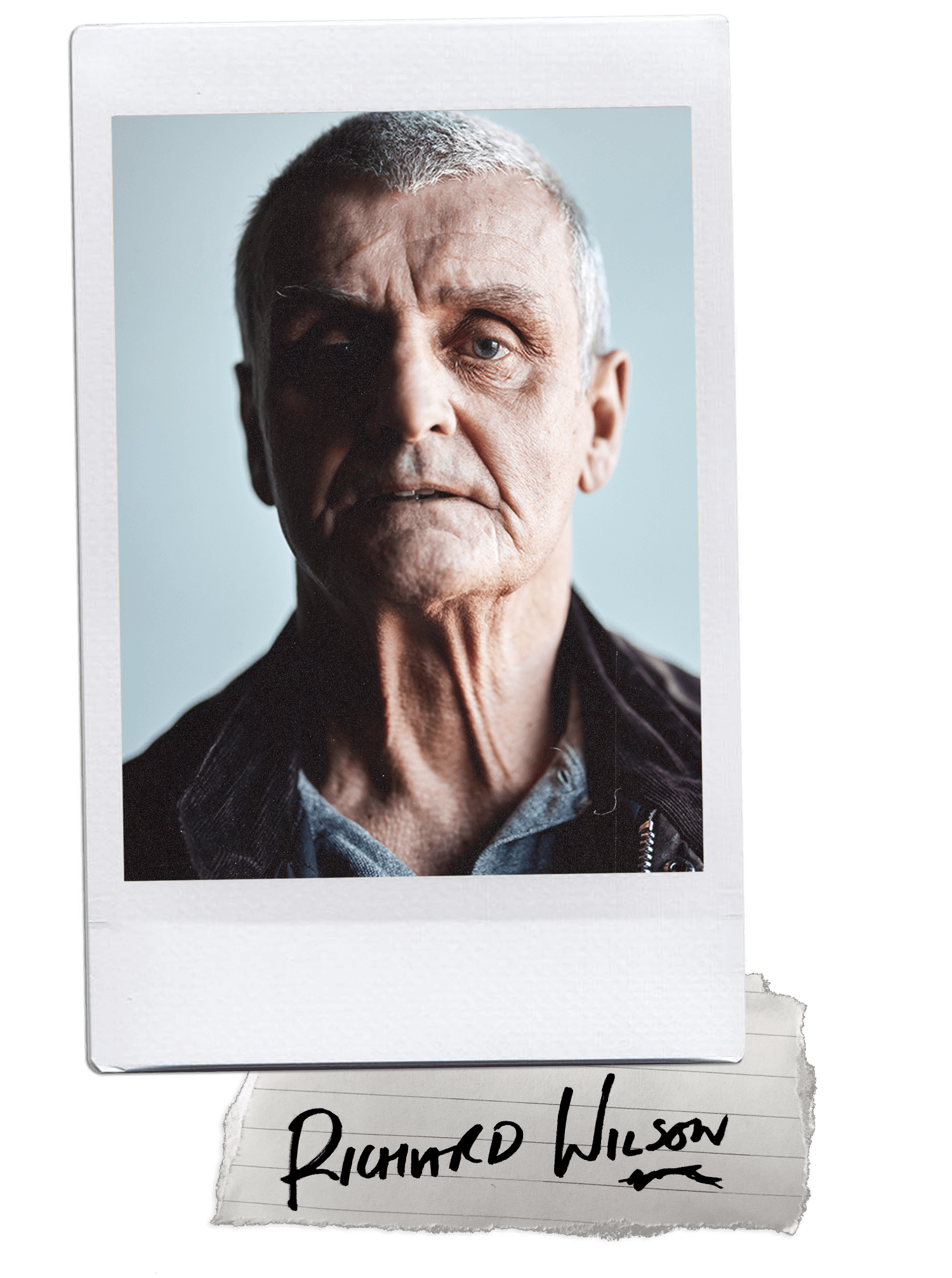

“I still can’t work out how there can be 97 deaths and thousands upon thousands of injuries as well as mental scars, and yet — where is the accountability? If 97 police officers had died at Hillsborough, it wouldn’t have taken 30-odd years to bring them to justice.” Alan has always known how to handle himself. As a child, he lived in Kirkdale, one of the toughest areas of Liverpool. His anguish has led him towards “extreme violence” but he is not alone. Like Alan, Richard Wilson is a former serviceman who believed he was immune to distressing scenes and conditioned to recover from awful moments.  He puts his divorce on Hillsborough. His wife Natasha was an intensive care nurse who studied psychology to try and get her husband to seek help. His way out of his problems was to hit the gym, which made him look great. Yet he was also a functioning alcoholic and prone to episodes of violence. This landed him in court on a couple of occasions. He concedes that he was lucky to avoid jail after using his car as a weapon on a pedestrian who got in his way while driving. “Fortunately, I slammed on the brakes.” That incident happened in Northampton, where he had moved to by 1989. Richard had grown up in Blackpool but his mum, Thelma, came from Speke and was nominated as Miss Liverpool in 1952. This meant he spent a lot of his summer holidays in the estates near Western Avenue. They were, he says, the best days of his life.

He puts his divorce on Hillsborough. His wife Natasha was an intensive care nurse who studied psychology to try and get her husband to seek help. His way out of his problems was to hit the gym, which made him look great. Yet he was also a functioning alcoholic and prone to episodes of violence. This landed him in court on a couple of occasions. He concedes that he was lucky to avoid jail after using his car as a weapon on a pedestrian who got in his way while driving. “Fortunately, I slammed on the brakes.” That incident happened in Northampton, where he had moved to by 1989. Richard had grown up in Blackpool but his mum, Thelma, came from Speke and was nominated as Miss Liverpool in 1952. This meant he spent a lot of his summer holidays in the estates near Western Avenue. They were, he says, the best days of his life.

Alan says he avoids shopping centres because the crowds remind him of Hillsborough. Martin says he always checks out the emergency exit, whichever building he is in. John Mulhaney, another survivor, will go to a restaurant and ask for a table in a corner of the room because it makes him feel safer when his back is against the wall and he can see clear spaces in front of him. Like Martin, John finds himself making excuses. He still misses family gatherings because of Hillsborough. Social occasions make him feel anxious.

On the morning of this group interview, he had to force himself to leave the house. “I’ve faked illnesses,” he says. “The thought of being in the same space with so many people frightens me to this day. Whenever I enter a room, I’m looking at how to get out. “My guilt is the same as it was in 1989,” he continues. “I ask myself: who was I standing on? I know that I stood on two people. I think, ‘Was it my weight that killed a child?’.”

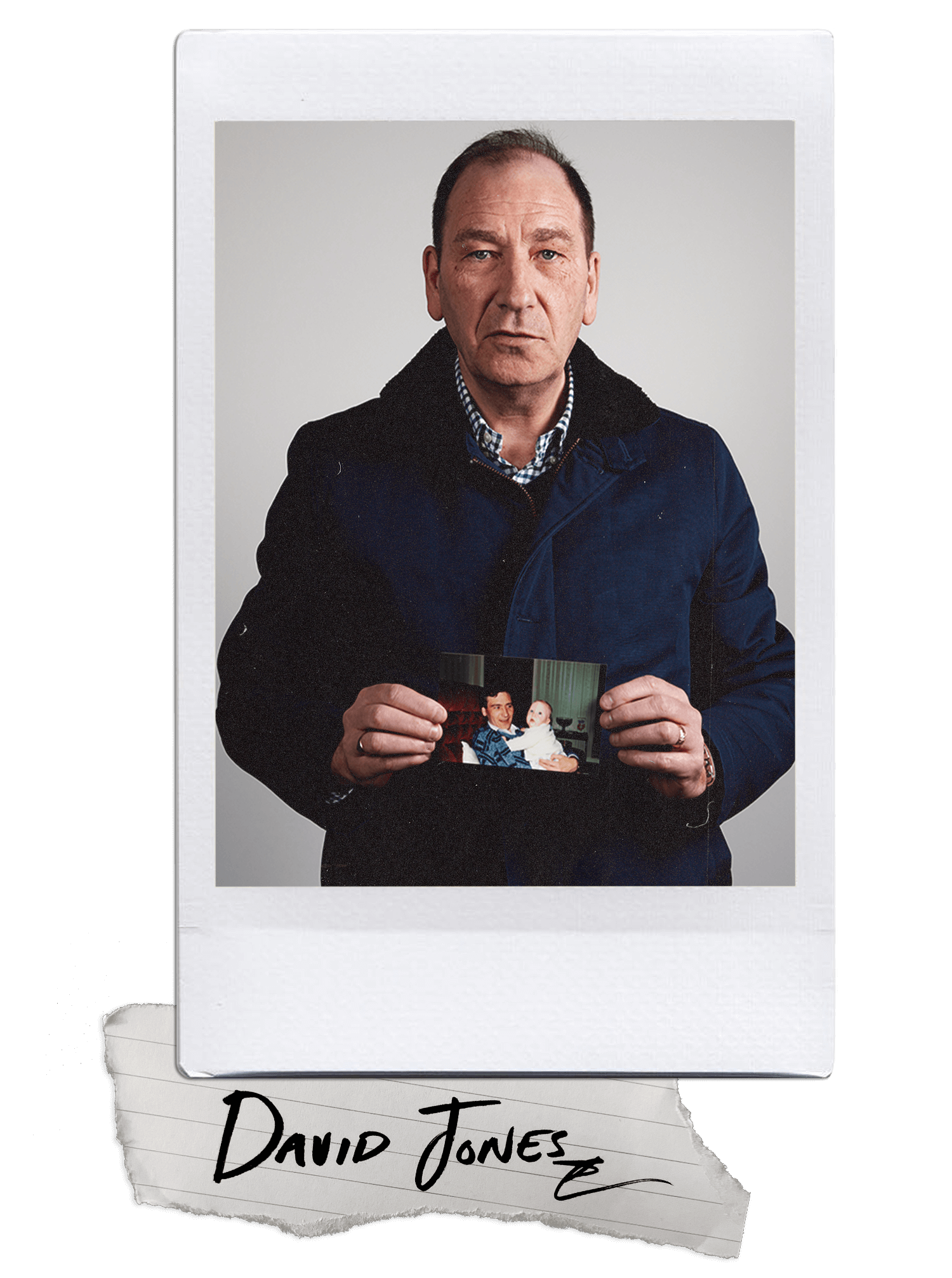

John emerged from the crush with bad bruising. A few days after the disaster, his shoulder was in agony, so he went to see a doctor who confirmed that his body had entered the process of shutting down on the terrace and this was not real pain but a release of nervous tension. The physical consequences were sharper for David Jones, who has lived with serious back issues ever since he escaped a crush that left him with peripheral neuropathic pain. He had attended Liverpool matches with his wife and he feels fortunate that she was not there that day. “We’d have both ended up dead because I’d have been too focused on trying to protect her,” he says.  Not far away on the terrace, Paul Dunderdale was trying to engineer space for himself and his brother Andrew, who was close to passing out. They had travelled to Sheffield in a group that included Graham Roberts, who was engaged to Paul’s wife’s sister, Sandra. “Three sisters met lads who loved football,” he says. “We’d go home and away and meet the girls in the pub later that night. It was too perfect.”

Not far away on the terrace, Paul Dunderdale was trying to engineer space for himself and his brother Andrew, who was close to passing out. They had travelled to Sheffield in a group that included Graham Roberts, who was engaged to Paul’s wife’s sister, Sandra. “Three sisters met lads who loved football,” he says. “We’d go home and away and meet the girls in the pub later that night. It was too perfect.”

After Graham’s death, Sandra met someone else but it was hard for him to cope with the consequences of living with someone affected by Hillsborough — “showing you how far the trail of pain could travel”. The solution was to move to New Zealand with Sandra. This prompted one of Sandra’s other sisters to join her. Though Paul’s wife was encouraged to emigrate as well, Paul wanted to stay in Wallasey.

“The indirect results of Hillsborough are immense. It has split our family right down the middle in terms of geography.” Paul’s job involves a lot of driving around the country. There have been times when he’s been travelling at 70 miles an hour on a motorway and thought, “This would be so easy, I could make it look like an accident. Financially, the family would be fine. But then, something has pulled me back.”

Paul identified Graham’s body at Sheffield’s Royal Hallamshire Hospital at 1.30am but only after he was made by the police to look at Polaroid photographs of other dead supporters. Though he made it clear he was searching for a 24-year-old male, it did not stop them from showing pictures of women and children. “Why did they not just show me the ones of men who looked like they were 24? It was inhumane.” More than a quarter of a century later, Paul contributed to Operation Resolve, which gathered evidence for the inquests that absolved Liverpool supporters. Though he had managed to stay with his brother on the terrace, he did not know what had happened to Graham after they became separated until he studied the footage and established that he was only ever three feet away when his life was taken away from him.

Some survivors of the pen prefer to speak anonymously because of the potential consequences that accompany full disclosure. One contributor suggests it might render him unemployable if he attaches his name to his story. He says Hillsborough has taken him to the rope section of B&Q, where he thought about ways of killing himself. He also thought about suicide through asphyxiation and the “exit bag”. He has considered how to make it look like an accident or a disappearance. This led to him spending time with a friend who was involved in finance, so his family would benefit from any insurance payout.

“I was methodically sitting down planning my death in a way there was not going to be as much collateral damage left behind,” he explains. A lot of his work was in London. He realised it would have been easy for him to accidentally make it look like he’d tripped over luggage on a busy platform before falling in front of a train. He even knew at which points trains on the timetable were travelling at their fastest, to ensure a cleaner death. He nearly killed himself through alcohol, sometimes racing through four bottles of wine a day. It was easy for him to consume gin and tonics by the pint.

All of this ruined his marriage. He was having another nervous breakdown when his former wife managed to get him to see a doctor late on a Friday night. It was the first time in more than a quarter of a century any medical professional knew about his experiences at Hillsborough. He had not seen anyone about his problems because he was concerned that the unzipping of his brain would lead to him being sectioned. You would not know about his suffering based on his appearance.

He looks — and sounds — sharp. In his late thirties, he got back on track for a while, holding high-level positions at international companies with billion-dollar turnovers. Like Martin, all of his energy went into his career. Though he was successful, Hillsborough was always there. Its presence in his mind means he finds it hard to trust anyone in authority, something that creeps into his work life. He sits on an array of boards and these roles are easier to maintain because they involve shorter chunks of time spent with colleagues every two to three months. When a job requires him to be with the same people nearby regularly, the toxicity in his personality becomes an issue — but he can’t see it coming.  Since 2016, he says his emotional resilience has collapsed. His behaviour has spun out of control, becoming more eccentric and explosive. He went from living and working in London, dining at all of the top restaurants, to sleeping in his car at a train station car park.

Since 2016, he says his emotional resilience has collapsed. His behaviour has spun out of control, becoming more eccentric and explosive. He went from living and working in London, dining at all of the top restaurants, to sleeping in his car at a train station car park.

On one occasion, he stopped his car in the middle of a motorway because his kids were arguing in the back seats. This led to him marching down the side of the motorway and sleeping the night in a central reservation. He has since left WhatsApp groups and avoids social occasions, quitting his last job in July 2021 because he concluded that he needed to treat trying to get better as a full-time occupation.

There have been dips in the meantime. Before Christmas, he was supposed to attend the 50th birthday of a friend he’d known since the age of eleven. After arriving in the car park of a Cumbrian pub, he reversed and drove home. Only a fortnight ago, he was in London when he, in his own words, “lost the plot”, turning a table upside down which damaged his own laptop. His friends spent the evening trying to clean red wine from the walls.

Philip Wilson was 17 years old when he was caught in a crush that left him with massive bruising across his abdomen and ribs, along with cuts to his head and his legs where some of the tendons had been stretched to the point he thought they might snap. Phillip recalls the sombre and anxious coach journey home, staring at the empty seats and worrying himself about the welfare of the people who were meant to be sitting in them.

He remembers arriving in Speke and heading to Cressington on the train, where it seemed like people chatting away at a bus stop had not heard about the events in Sheffield just a few hours earlier. In these moments, it felt like he was living in an alternative reality. This prompted his body to give way as he collapsed to the floor.

That night, his parents were at a family wedding in Southampton. Philip had refused to go because he did not want to miss the semi-final. So, he went home to an empty house. He ended up sleeping in the spare room of a concerned neighbour, waking up the next morning in an unfamiliar bed not knowing whether he was dead or alive.

By Monday morning, he was back at Quarry Bank School, where John Lennon was a former pupil. None of the students — even those who had been crushed on the terraces of Leppings Lane terrace — spoke about what had happened to them over the weekend. “Bit shit that,” was as far as it went. Though Philip had achieved nine A to C grades in his GCSEs and expected to go to university, he flunked his A-Levels and he was unable to hold down a job he was proud of until his thirties.

Aged 50, he says the disaster has had a “corrosive” effect on his life, completely altering his personality. Somehow, he can rationalise what happened on that day. What troubles him most is what happened afterwards, the lies and the cheating. “If figures in authority had shown some humility and culpability, it would have still been shit but I’d have been able to come to terms with it,” he says. “Until that happens, I won’t be able to process everything that has happened since.” He cannot bring himself to refer to the name of the stadium where Britain’s worst football disaster happened. He has always called it “H”.

The image many people have of women in the context of Hillsborough has been of mothers crying for the deaths of their husbands and children. Rarely have the voices of the women who survived the central pens of the Leppings Lane terrace been heard even though, according to Alison Willis, there were lots of women in the crush.

Alison’s story highlights how Hillsborough should be remembered as a national tragedy. She was born in Mansfield and supported Liverpool because her father, Doug Bennett, played for Huddersfield Town when Bill Shankly was manager. Shankly would pick him up in his car at the bottom of the street and drive him to training. After Shankly secured legendary status at Anfield, the Bennett children were brought up on a diet of tales relating to Shankly’s genius. While Liverpudlians like Alan Radford wanted to get out of the city to escape a relentless torture, Alison’s wish that she’d been in Liverpool in the aftermath of the disaster, to be around people who understood what she was going through, shows there was no escape from the despair, no matter where you were.

“I felt trapped,” Alison says. “In Mansfield, I felt out of it completely.” Her true friends were good to her but the problems started when she was surrounded by people she did not know so well. Nottinghamshire had a rivalry with Merseyside because of the success of Liverpool and Forest towards the end of the 1970s. “I’d get called ‘Scouse scum’ and some people would tell me that I’d killed my own. My answer to them would always be the same, ‘You weren’t there…’.”

From Hillsborough, the drive back to Mansfield was only an hour but the journey seemed to go on forever. For Alison, it felt as though she’d just watched a harrowing movie, only here she was one of the characters. Two days later, on Monday morning, she was back at work in one of Mansfield’s breweries. Her boss seemed genuinely concerned about her welfare but some of the staff were just being nosey before the questions started, those like, “‘What did you see?’,” and “‘Is it true what they are saying in the newspapers?’.”

Supporters and police take an injured person away on a stretcher (Photo: AFP/AFP via Getty Images)

Support of sorts came from her mum, but she was the wife of a miner. “The family culture in the collieries has always been the same, you have to find a way to pick yourself up. From time to time she would remind me, ‘You’re not doing anyone favours here…’.” Nobody understood, therefore, the torment of police officers arriving unannounced at the brewery’s reception and escorting her to a station, where they asked questions about what happened at Hillsborough, not in an interview room but from a cell.

“It was at that moment that I realised how much of a fight it was going to be for the truth to come out.” Her sons, who had learned to count by looking at a poster that included the numbers of the Liverpool squad, are adults now but Alison insists they call her whenever they attend a football match, just to let her know they are OK.

“I can’t relax until I’ve heard their voice,” she says. When Mansfield hosted Liverpool in an FA Cup match in 2013, the boys had to leave a pub because of the comments being made about Liverpool supporters. They had inherited an understanding of Hillsborough because of the impact it had on their parents.

Alison had been at Hillsborough with their father, then her boyfriend. He did not want to talk about his experiences in Sheffield but he was never offered counselling either. This led to him drinking heavily. In an attempt to salvage the relationship, they got married but a couple of years and two children later, they separated. He died in 2016, an alcoholic, distant from his former wife and kids.

Nicola Golding was left with broken veins all over her face. Both of her eyes had turned black. There was bruising on her sides. She was in shock and the doctor advised her to drink plenty of sweet tea. Two weeks later, Nicola was back at work with the scars of Hillsborough still visible across her body.

Until that point in her life, she had been career-driven. Against her mother’s wishes, she had left school in Walton to find a job that could offer her family adequate financial support. In the 1980s, she had taken part in a youth training scheme, working in a marketing department, while passing through college with qualifications in business studies. With few job options in Liverpool, a city plagued by huge unemployment, she worked for six months in a factory that made fuses before landing a role as a marketing executive in a building firm. She was in pursuit of her dream of becoming a telemarketing executive having become a manager at a company shortly before the Hillsborough disaster. This contributed to her wanting to return to work as quickly as possible.

The marks on her face, caused by asphyxiation, meant she was conscious of how she looked. Nicola had been a lively, confident and determined person before the disaster but now she was insecure and frightened. There was a stigma attached to counselling, especially for women. She was having lots of time off because of medical and psychiatric appointments. The stress led to her suffering from pleurisy. Breaking down at work made her feel embarrassed. Going home made her feel like she was letting her colleagues down. In her head, she had become a failure.

The coverage of Hillsborough in the press made everything worse, adding disbelief and anger to her senses. She was unable to cope and eight months after the disaster, when Nicola resigned from her position at the telesales company, it felt like all of her dreams had been snatched away even though she received an outstanding reference that stated that she had left for “personal reasons” having completed her work to a high standard. There had been an expectation that she would eventually command a senior position that involved a much higher salary and a car. Nicola was sad, angry and disappointed in herself. Now, she was possessed by restlessness and irritability, placing pressure on her relationship with Keith, her boyfriend who had also been crushed in the disaster. He became withdrawn and she worried about his safety whenever he wasn’t with her.

As soon as she entered a room filled with people, she wanted to escape. There was anxiety whenever she entered an elevator. She stopped driving lessons because she felt like she was endangering other people whenever — at random moments — her head began to fill with thoughts of Hillsborough.

Diagnosed with a “reactive anxiety depressive state” from which it was not clear how long it would take to recover, a report also stated, “there is a risk that her awareness of coming close to losing Keith may become a long-term problem in their relationship.” Like Alison, Nicola married her boyfriend but got divorced. Her life would never be the same. The flashbacks were like sitting in front of a television screen constantly. It was impossible to push the images to the back of her mind. She was plagued by doubt.

No matter where she worked after Hillsborough, she wondered what people thought of her. The only solution was to move away, to Cyprus where writing a book about her experiences was cathartic but not cleansing. In the 33 years since Hillsborough, Nicola has tried to kill herself three times.

Eileen Richardson used to work at a petrol station in Standish, just north of Wigan. At around 3.20pm on the day of the Hillsborough disaster, a man appeared at her counter. He had not filled up his car and he did not wish to buy anything. He just stood there, looking at her. Nobody else was in the forecourt. When Eileen asked, “Can I help you?”, he replied, “Everything is going to be OK…”

Eileen had spent the previous 15 minutes clinging to words being transmitted from the radio set behind her. Something bad was happening in Sheffield, at a football stadium nearly 70 miles away. “My sons are there,” she told the man. “Oh, they’ll be fine — don’t worry about it…” With that, he turned around and walked out of the door. Standish is a small place where everyone knows everyone else. The customers at the petrol station are regular. Yet Eileen had never seen the man before and she never saw him again.

One of her sons, Graham, who survived the crush along with his brother, John, says that Eileen was never able to explain this mysterious exchange. The rest of the Richardson family put it down as a strange coincidence. Eileen had grown up as a protestant and believed in god, but she was not spiritual.  “It could have just been a bloke trying to calm a distressed woman down, who’d forgotten what was going on around her,” Graham reflects. “Everyone has their own way of dealing with Hillsborough. I survived along with my brother, so it was a story my mum felt like she was able to share. It is weird she never saw him again, though.”

“It could have just been a bloke trying to calm a distressed woman down, who’d forgotten what was going on around her,” Graham reflects. “Everyone has their own way of dealing with Hillsborough. I survived along with my brother, so it was a story my mum felt like she was able to share. It is weird she never saw him again, though.”

Ordinarily, Graham would have been at Villa Park for the other FA Cup semi-final. He supported Everton and they were playing Norwich City. Yet tickets for that game were harder to come by. His brother, a Liverpudlian, had a spare for Hillsborough. Rather than boarding a bus from the Stork Inn pub in Billinge and heading towards Birmingham, he departed for Sheffield after a morning shift for Wigan council, clearing a market floor.

Around the time his mum was talking to the mysterious character in the petrol station, he had made it out of the Leppings Lane terrace and into the concourse behind the stand. He remembers approaching a policeman, who did not seem to know about the nightmare unravelling beyond the dimly lit tunnel from which Graham had just escaped.

When Graham tried to go for a wee, nothing came out. John, whose veins in his face and neck were already visible, had the same problem. They had travelled to Sheffield with two of John’s friends, who became separated on the terrace. Vincent, a father of one — who Graham had only met for the first time that day — was crushed to death.

“We were laughing and joking on the bus and ten minutes later, he was gone,” says Graham, who felt like he’d been given “a good hiding.” Like so many other people who nearly died in the Leppings Lane terrace, he reported for work two days later and by Monday morning he was picking up bins on the streets of Wigan.

Graham was 24 when Hillsborough happened. He had been an active sportsman but he soon found that his body wasn’t allowing him to compete to the same standard. Five years after the disaster, he stopped playing football. Twelve months after that, he could not play cricket. In 1997, he was admitted to hospital for trauma in his neck, where he discovered that some bones were out of place. He did not tell the doctors he had been at Hillsborough because he did not want to relive what he had been through.

Thirty-three years later, he suffers from psoriasis on his back, brought on by stress. Lots of his teeth have also fallen out. There is an image he cannot escape, no matter how hard he tries. “There are faces,” he says. “They’re swaying in front of me. I don’t know whether or not they are alive or dead. They look asleep and, in the distance, I can hear screams. It’s worse when I’ve had a drink. I’d close my eyes and they’d be there.”

There are times when he feels the exhilaration of normality and that is because Hillsborough is not on his mind. Suddenly something would take him back and he would go into his shell for several days, not speaking to anyone. He says he was never suicidal but he feels an emptiness. “I don’t want to do anything with my day.”

Until the inquests found that supporters were not responsible for what happened at Hillsborough, Graham would sleep with the light on at night. He still feels guilty because “it feels like we dodged a bullet and lots of others didn’t. Young girls and lads, all gone. They were down in front of those barriers a long time before kick-off, minding their own business”.

It took 30 years for Graham to see a counsellor. It turned out that the counsellor’s brother had died at Hillsborough. Everyone knows someone, even if you are from Wigan. The only person at work who knew was his boss. Graham chose not to tell anyone else what he’d been through because he expected pushback. Lots of people in Wigan trusted the police because they viewed authority through the image of the friendly local bobby. Graham felt isolated in his thoughts.

In the early years, there were a couple of fights. He was in a Wigan pub called the Freemasons one night in 1990 when he overheard a conversation. A policeman was telling his mates about what he had heard from colleagues in Sheffield. “The copper was a bully boy. I told him he was wrong. Ended up in a big scrap. “You’d hear it all the time: ‘You deserved it…’. I was, like, ‘What? I’m an Everton supporter, me… and no one deserves that’. What they were calling Liverpudlians, they were calling me and I’m a Blue. I was there. I felt just as wronged as everyone else.”

When Graham entered pen four of the Leppings Lane terrace, in his possession was a match ticket, a £10 note and a packet of Extra Strong mints. Half an hour later, his paper belongings were unrecognisable and the mints had turned to dust, mashed under the pressure. It was a sunny day, T-shirt weather. Just outside Sheffield, the police stopped the Eavesway coach he was travelling on to check whether anyone was carrying alcohol. The intervention was standard procedure in the 1980s but it made the bus later than it might have been.

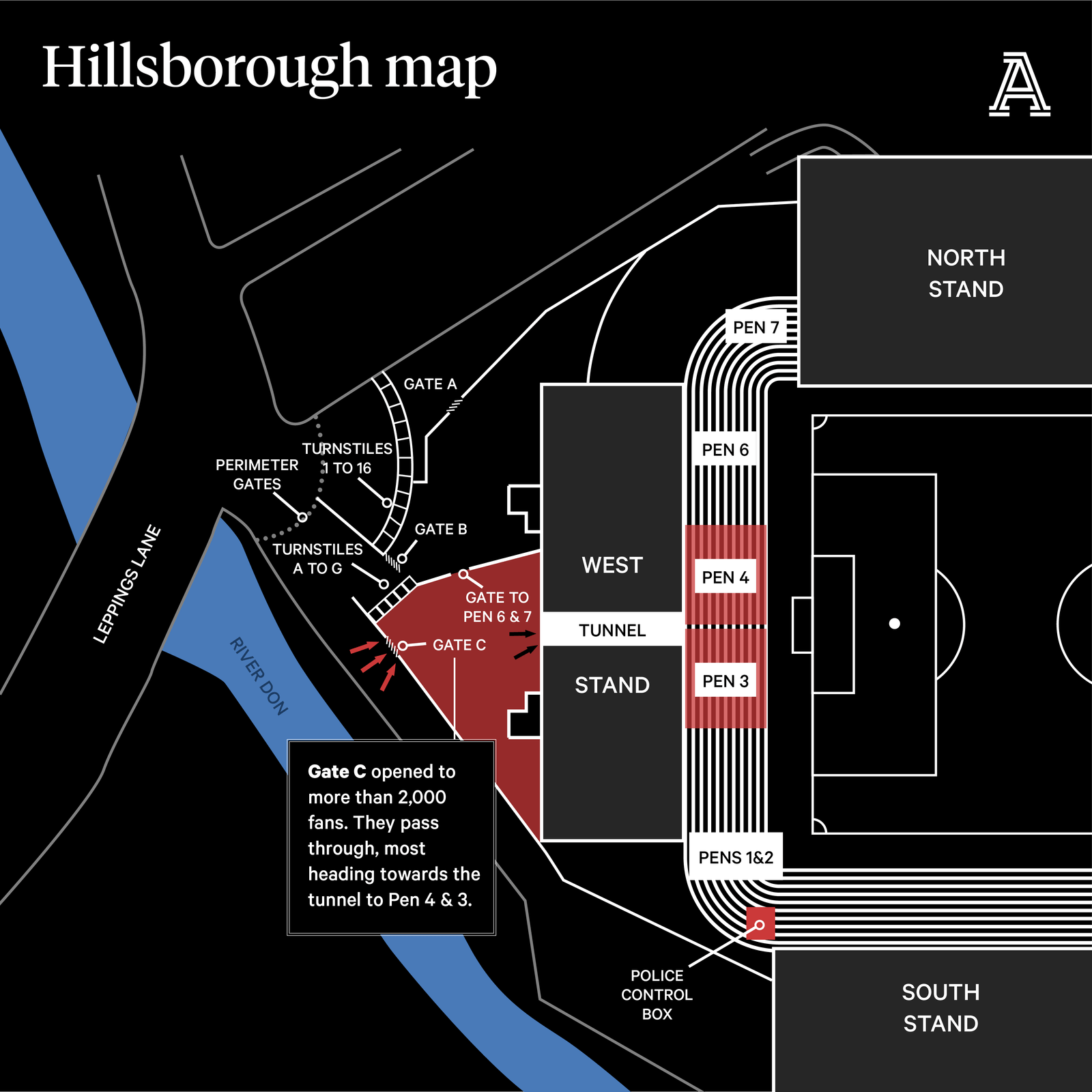

Roadworks on approach to Sheffield had pushed the arrival time of lots of buses back even further. Kick-off was 15 minutes away and Graham hated being late. John suggested the four men jog towards the stadium to ensure they didn’t miss anything. Outside, they were greeted by pandemonium. No police checkpoints. No funnelling system. He could hear supporters saying this had been in place the year before. Why wasn’t it now? Suddenly, the gates opened to the Leppings Lane terrace. “Even if you didn’t want to go into the ground at this point, you were going in…” He can remember the chant, “Liverpool, Liverpool, Liverpool…” And that is when it happened.

Graham got kicked in the back of his head. Someone behind him was struggling for air and somehow, he lifted himself upwards to climb over a sea of people. Initially, Graham was annoyed at the person’s carelessness. The horror of the pen developed very quickly but for Graham, it felt slow because some things seemed normal.

That, in itself, remains a horrifying element of the ordeal: when people imagine tragedies, they tend to think of everything being visibly wrong but at Hillsborough, a football match was unravelling just a few yards away at a frenetic pace. Liverpool’s Peter Beardsley hit the crossbar with a shot and there was an enormous gasp.

Graham says the crush was so bad that he did not know whether that moment had happened right in front of him or at the other end of the ground. He had not been able to establish which way Liverpool were kicking. The Richardsons had separated from Will and Vincent, but they were next to one another, their feet not touching the ground. John’s head was resting on Graham’s shoulder because there was nowhere else for his head to go. Graham was in pain.

“It felt like a snake strangling its victim.” He started to pray, asking for God to help both of them. “I reckon we had a minute left.” That was when John told his brother words he will never forget. “He said, ‘Graham, I’ve gone… I’ve gone…’.” Nearby, Paul Dunderdale’s brother Andrew was turning blue.

The word “somehow” appears a lot in the stories of everyone who escaped the Leppings Lane terrace. For Paul and Andrew, it is there again. “Somehow, I managed to turn him around.” There was no way out at the front because the police were stopping supporters from climbing over the fence by using their batons. Using a photograph, Paul is able to show what happens next. Wearing his red and white bucket hat, he is being lifted onto the upper tier of the terrace. His brother had gone upwards ahead of him. You can see the strong arms of a man and his palms are on the soles of Paul’s trainers. “An absolute hero,” according to Paul. “He was a big, fat guy. He saved lots of people. I don’t know who he is.”

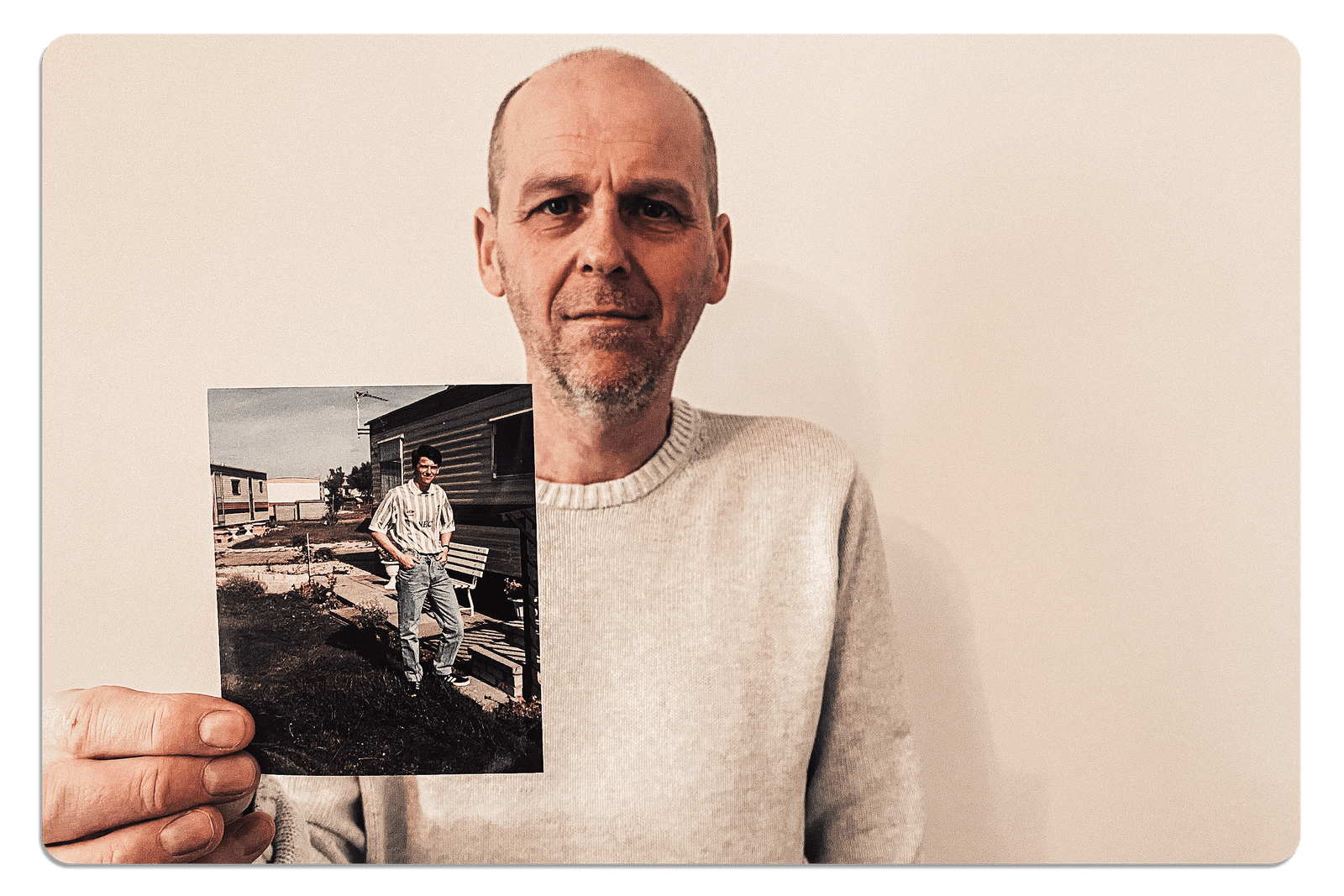

Paul Dunderdale hanging from the stands (left) and at the meeting with the other survivors

For Paul, the horror really started when he was able to get his breath back and look down at what was happening from a higher position in the stand.

“You could see a sea of bodies lying on the floor. I had a horrible feeling we’d lost someone.” Like the Dunderdales, David Jones had travelled to Sheffield from Wirral but he was alone on the Leppings Lane terrace because his friends were in other parts of the ground. This meant he was isolated in his thoughts as he was being crushed, unsure whether he’d be able to survive.

David arrived at Hillsborough around 2pm and even then, there were chaotic scenes outside the turnstiles where the police had lost control. This did not stop him from taking up his usual position behind the goal, about halfway up the terrace. He had been in a lot of bad crushes but this one was getting worse and worse. David heard a whooshing noise and more fans started entering the pen through the tunnel. “It was uncomfortable already. Why were all these people still coming in when it’s obviously full already?”

The police blamed Liverpool supporters for pushing a gate when really, an order had come from the match commander’s control tower overlooking the pen to open up and relieve the pressure. Once inside the stadium’s grounds, there were no police, stewarding or signs guiding supporters away entering an already uncomfortably crowded pen. David had a packet of cigarettes in the back pocket of his jeans but he was unable to access them.

“The guy next to me was smaller and I had my elbow in his windpipe. I couldn’t move. He fell to the ground and I couldn’t do anything about it.” David says he never saw a ball being kicked. The crowd ended up moving him and suddenly, he was facing the stand rather than the pitch. He could see people like Paul and his brother being dragged upwards onto the higher terrace of the stand.  It was at this point his life flashed before him. Everything started to happen in slow motion. He had become a father a year earlier, to a son. “I thought, ‘Shit, I’m never going to see my lad grow up’. I thought about my missus. Had I done my will? I thought, ‘Christ, how’s she going to manage?’.” John Mulhaney had been one of the supporters carried into the pen through the tunnel by the weight of the crowd. In doing so, he had become separated from his father-in-law, William — “a big, strong man standing at 6ft 4in,” whose petrified words to John outside the turnstiles were, “We’ve gotta get out of here.” That was just before the police opened the gates, taking smaller men like John in the direction of the central pens whether he wanted to or not.

It was at this point his life flashed before him. Everything started to happen in slow motion. He had become a father a year earlier, to a son. “I thought, ‘Shit, I’m never going to see my lad grow up’. I thought about my missus. Had I done my will? I thought, ‘Christ, how’s she going to manage?’.” John Mulhaney had been one of the supporters carried into the pen through the tunnel by the weight of the crowd. In doing so, he had become separated from his father-in-law, William — “a big, strong man standing at 6ft 4in,” whose petrified words to John outside the turnstiles were, “We’ve gotta get out of here.” That was just before the police opened the gates, taking smaller men like John in the direction of the central pens whether he wanted to or not.

In the tunnel, “the noise was horrendous — people were going down. They were screaming”. Pens three and four were central on the terrace and John was carried left, into pen four. “It was like being in an ocean: one minute you’re over here and the next, you’re over there.” There is a famous photograph of two girls being crushed against the fence at the front of the terrace. John was just behind them. He did not intend to be there but that is where he ended up. John can remember looking towards the heavens and “the sky looked gorgeous”. It was only years later when it was explained to him that this happened because he was entering an unconscious state. Suddenly, he’d snap out of it. He caught his breath. Somehow, he found the strength to climb the fence. He thought he was free but a policeman pushed him back in.

This led to more harrowing moments, like when he stood on something softer than concrete. “It was a dead body. Though I had no choice, it’s something you never get over.” Martin Roberts lives with the same sense of guilt. Just before kick-off, he realised he wasn’t able to pull his arms above his chest. He began to feel faint. He started wobbling. Someone grabbed hold of him. Then a barrier snapped and he went with it. In getting back up, he was climbing over people. There were women and children.

“The stench of sick was horrendous. People’s faces were getting cooked. The smell will never leave me.” From his position, Richard Wilson could see the heat rising from the lower part of the pen. He remains a powerfully built strongman trainer, who then weighed nearly 100kg. There are things he wishes he could have done to try and help people but he was unable to because he couldn’t move, no matter how hard he tried. On a trip to Belize with the army, he had felt the squeeze of a snake around his neck and this was similar. “It was like being gripped by an anaconda.”

Richard had a ticket in the Forest end but he went to the Leppings Lane side of the ground to see whether he could buy one to stand with the Liverpool supporters. When the gate opened, he too was swept away. He remembers pushing another man to the side of the tunnel in an attempt to guide him. Once in the pen, the men saw a teenager on the floor. Richard used his right arm to pick the teenager up on one side and the other man used his left arm. They held him for as long as they could. But eventually, the teenager gave way.

Richard had been in the army for 12 years, serving in Northern Ireland. The job opened up his senses and he tended to know when something was wrong. He could not believe his eyes when he saw a policeman by the fence with a beard, using his baton to flick back the fingers of supporters who were trying to escape. In front of him, he saw someone else fall to the floor and with another man, he tried to pick him back up. He sees it as a failure that he was unable to.

“I don’t know whether he lived or died and it haunts me.” Richard was a recruitment officer in the army. He felt like he was mentally strong. When he saw the man he had entered the pen with trying to escape as the pressure in the crowd eased, he intervened, telling him that what he’d already done was incredibly brave — that if he left now without helping, he would regret it for the rest of his life because he would never be able to forgive himself. Richard also knew combat first aid. His training meant he was in a position to help when the crush subsided, revealing a terrifying sight.

There were bodies all over the place. One man had died bent over double. His trousers had fallen down. Richard can’t remember whether it was him or someone else that pulled them back up. Another man nearby was also dead but someone was pounding on his chest, trying in vain to keep him alive.

Fans who escaped wait on the pitch (Photo: David Cannon/Allsport

When the emergency services finally arrived, a policeman grabbed him. “I said, ‘I’m fucking trying to help here!’. They ended up kicking me out of the pen, even though I could have helped. Another regret I have to live with. Why didn’t I go back?”

Like Richard, Alan Radford had served in the forces where he was taught chest compressions and like Richard, he was stopped from helping. He had experienced the crush outside the turnstiles but went with his wife to the main stand, from where he could soon see a supporter climbing the fence. “His arm was snapped and the bone was sticking out.” When he tried to make it onto the pitch to help a recovery effort led by supporters, as most policemen formed a human cordon on the halfway line, a baton was applied to his back. An officer said, “‘Get back in there, you Scouse bastard’.”

The night before the disaster, Alan had been for a pint and a couple of games of pool at the Liverpool Supporters Club on Breck Road in Anfield. He had a ticket in the Leppings Lane terrace. “A lad came into the club asking for spares, so I sold it to him, face value. I don’t know what happened to the lad. It haunts me to this day. He could be dead, he could be alive; I don’t know. I can’t picture his face.”

For Nicola Golding, it is the faces that plague her thoughts. A season ticket holder at Anfield, Hillsborough had been her first away game. When she left home in Walton earlier that day, she was dressed in black. Nicola’s mum forever regretted making the joke that her daughter looked like she was on her way to a funeral. A few hours later, she was six steps from the front of the pen. Her friends reassured her that the congestion would ease off but it didn’t. She ended up on the second row — but only because people in front of her had fallen over, into an abyss.

Somewhere in that abyss was Philip Wilson. He had been among the first 20 Liverpool supporters to enter the central pens. Ninety minutes or so before kick-off, he was lying down on the concrete without a care in the world, holding a match programme over his head to protect his eyes from the sun’s rays. For a while, there was enough space to hold conversations with familiar faces. One of them was Phil Hammond, two years his junior. Only a few weeks earlier, they’d been on a school skiing trip together where they had developed a rapport. Hammond was quite small and Philip advised him not to stand at the bottom of the terrace because he might not be able to see the pitch. Within an hour, Hammond was dead.

Twenty minutes before kick-off, Philip’s risk register was beginning to tweak. He was a season ticket holder at Anfield and a regular at away games. He had a decent understanding of crowd patterns, the way they surged and eased. It was already way past the point of anything he had experienced before. The pressure was coming but it wasn’t releasing. He is convinced there were fatalities on the terrace before the game kicked off. He remembers seeing an old man who had passed out, possibly beyond the point of no return. Surely, he himself would be OK? He was captain of his school’s athletics team. He was in good shape physically.

Suddenly, however, he was up against one of the crush barriers, which he compares to scaffolding poles. His feet came off the floor and the steel was grinding against his rib cage and solar plexus. It felt like he was drowning in the thinnest air. He could see other people trying to get more space for themselves by trying to lift their arms above their heads but this left their ribs unprotected from the crush. It was the worst thing they could have done. Philip’s face began to scrape across the barrier in front of him. He figured that his skull was going to get crushed. This prompted him to push himself downwards, believing he’d be able to get back up on the other side. Now, his head was on the floor, facing down on the gradient of the terrace.

The lights were off. It was pitch black. He was fighting for his life. Everyone above was doing the same thing. His head was being stood on repeatedly. There was no air. The heat was unbearable. He was asphyxiating. His memories from this point are hazy because he drifted out of consciousness. The next thing he remembers is being passed over the top of the perimeter fence. His jeans caught on one of the metal spikes at the top of the fence and this caused him to pivot before he landed on the pitchside gravel.

Meanwhile, Nicola was struggling to stay alive. Her friend Arthur died minutes after his words of encouragement helped maintain her own focus. She feels guilty that she survived and he didn’t. Just watching a television programme about Hillsborough makes her hyperventilate. She is taken straight back into the hell of the pen. Then, when she closes her eyes at night at her new home in the mountains of Snowdonia, the nightmares begin.

There is a vision she cannot escape from, no matter where she is living. Wherever she goes, Hillsborough follows. “I am in the Leppings Lane terrace and I manage to turn around. In front of me are three boys huddled together. My nose is pressed up against the face of one of them. His skin is the colour of newly-fallen snow. I tell myself they are sleeping.”

If you would like to talk to someone having read this article, please try Samaritans in the UK or US

(Photos and artwork by Mark Robinson and Sam Richardson)

Read the full article here