This season’s battle for the Premier League title is now unquestionably a three-horse race.

In May, Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City will become the first side in English football history to win four titles in a row. Or Jurgen Klopp will win his second Premier League title before departing Liverpool. Or Mikel Arteta will lead Arsenal to their first league title in two decades.

Whichever outcome transpires, the victorious side will have depended on a player who has fulfilled an unusual role this season.

Football is reasonably well accustomed to the concept of a ‘9.5’ — those players who are somewhere between a No 9 and a No 10. But what about the concept of an ‘8.5’? This has never really worked as a phrase — if a No 8 is a midfielder who has the licence to drive forward, and a No 9 is a striker, then a player who is somewhere between the two is not an 8.5, but what we all understand as a No 10.

This season, though, the term 8.5 might make sense.

All three title contenders have fielded a player who has played as an out-and-out centre-forward and in a role tucked into a midfield trio in a 4-3-3. For Manchester City, it’s been Julian Alvarez. For Liverpool, it’s been Cody Gakpo. And for Arsenal, it’s been Kai Havertz.

The first of those three to fill both roles was Gakpo, who played in the left-centre role in Liverpool’s new-look midfield on the opening weekend of the season in a 1-1 draw at Chelsea.

Although Liverpool were still looking to reinforce their midfield — they would eventually lose out on Moises Caicedo to their opponents that day, while Wataru Endo was still to arrive — Gakpo was preferred in that role over Curtis Jones, a more obvious candidate for the midfield slot. Gakpo has played there on other occasions since.

But Gakpo has also played up front, and at times has acted like a proper No 9 rather than a false one — take this equaliser at Wolverhampton Wanderers, for example, which was a classic poacher’s effort from a scuffed Mohamed Salah shot.

Overall, Gakpo has played almost exactly one-third of his minutes in midfield, one-third out wide, and one-third as Liverpool’s primary striker. There is, of course, fluidity in the front three, particularly when Darwin Nunez has played from the left, but it shows how versatile Gakpo has been.

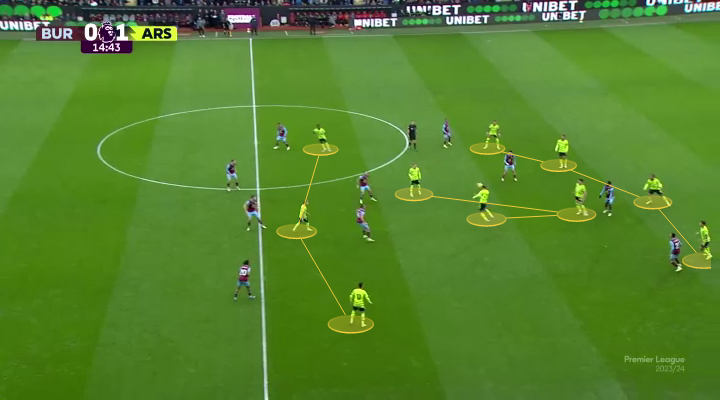

Havertz’s experience at Arsenal has been intriguing. For most of the campaign, he’s been in that same midfield role as Gakpo, tucked into a left-centre midfield position. Here he is against Burnley at the weekend, winning a header from a long goal kick.

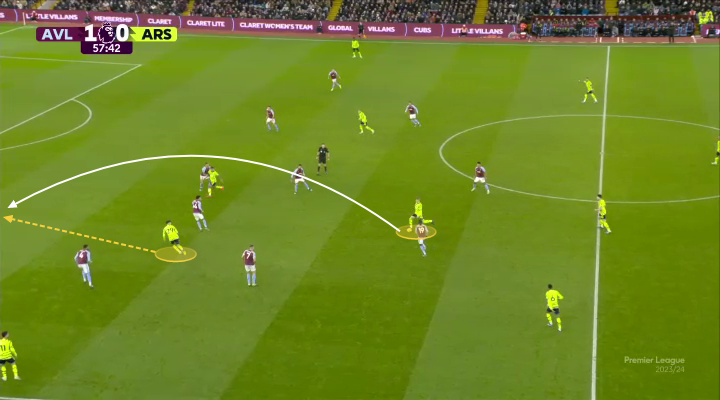

That role has worked particularly well for him when Oleksander Zinchenko has been fielded as the ‘left-half‘, stepping forward into midfield to take up that left-centre role and allowing Havertz to spring in behind. Here, they combine for a good chance, when Martin Odegaard should have finished from Havertz’s cutback.

But again, does Havertz act like a false nine when playing up front? Not really. He has contributed to two late Arsenal winners this season, first when laying off the ball for Gabriel Martinelli’s deflected strike for the only goal in the 1-0 win over Manchester City.

Havertz also headed home a deep Bukayo Saka cross for the only goal at Brentford.

Havertz still doesn’t look entirely comfortable in front of goal, although his returns are improving. But when he plays up there, he’s more of a target man than he is a floating forward who comes deep, like Leandro Trossard does, which is exactly what Arteta said on his arrival. “He gives us something different,” the Arsenal manager said in July.

“His height, for example, where he can be a target man if we need to beat the press. He’s playing at centre attacking midfield for now but I’m sure throughout the season he’ll be used in different positions.”

So far, it’s been 90 per cent of the time in midfield and 10 per cent of the time up front.

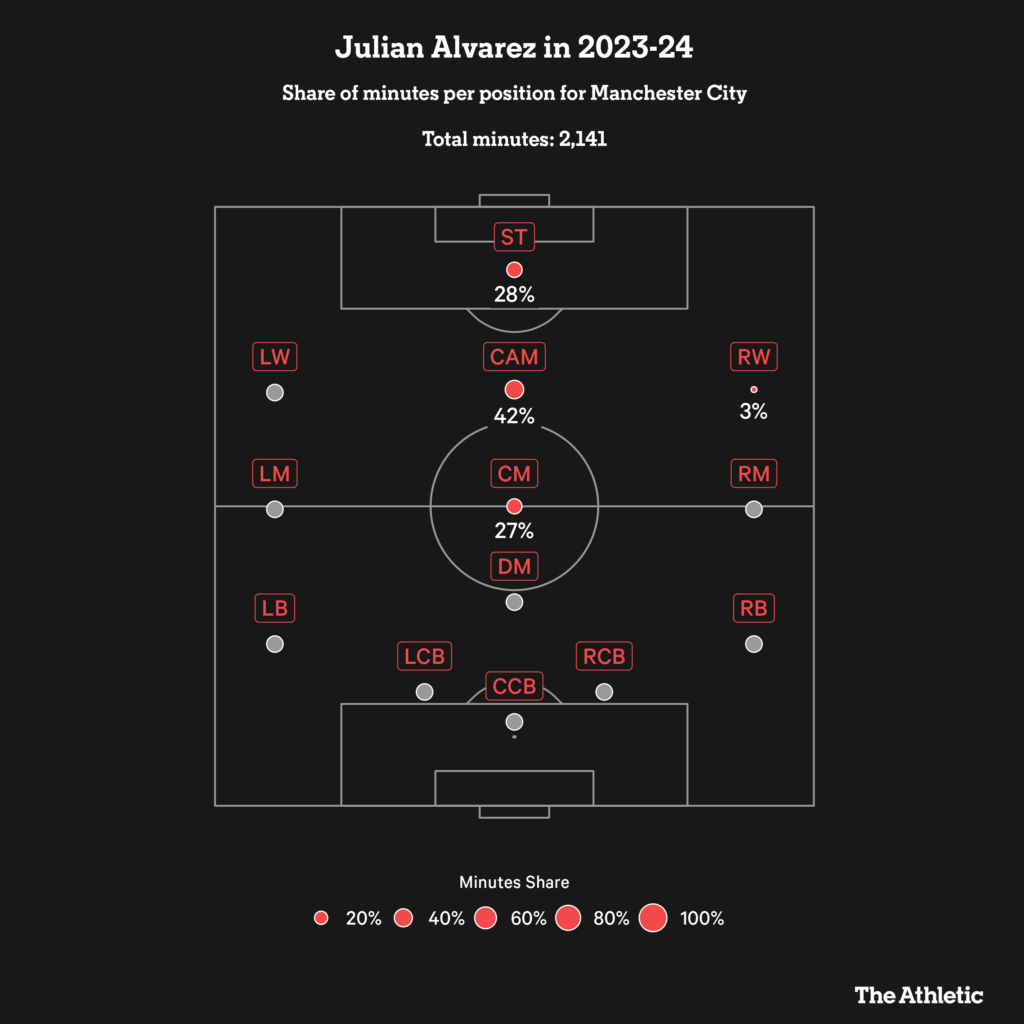

Then there’s Alvarez, who won the World Cup just over a year ago playing as No 9, while also getting through the defensive work of Lionel Messi, who was playing as a No 10. That convinced Guardiola that he could play in conjunction with Erling Haaland.

The share of his minutes in each position is interesting — he has primarily played as a No 10 in a 4-2-3-1, but that was only really possible when Kevin De Bruyne was out injured. Otherwise, he has played roughly equally up front and in a central midfield role.

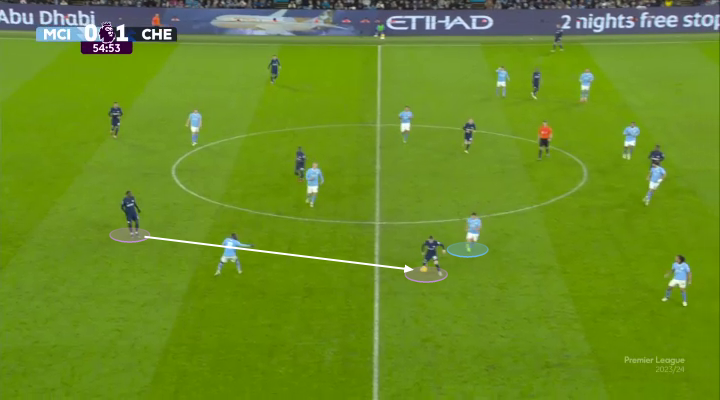

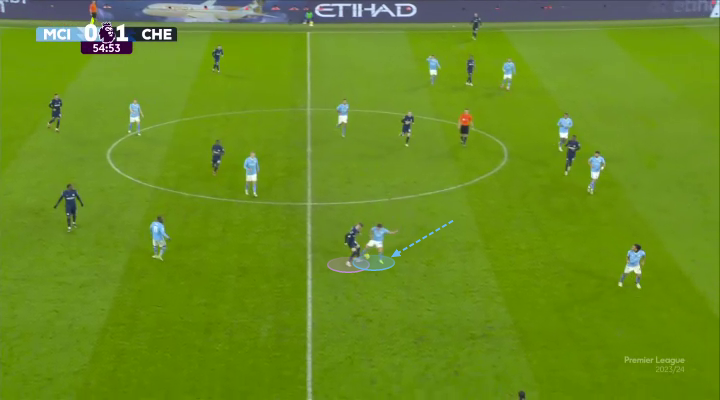

When alongside De Bruyne at the weekend against Chelsea, Alvarez’s job was about dropping back next to Rodri to form a double pivot without possession.

This is a huge ask for a footballer who is accustomed to playing as a striker — there’s a big difference between pressing from the front and scrapping in midfield — and on two occasions, he was exposed defensively by Cole Palmer’s trickery. First, as Palmer prepared to receive a short pass from right-back Malo Gusto, Alvarez seemed in a good position to shut him down.

But Palmer then threw Alvarez off completely, by pretending to suddenly sprint past him, then checking back and receiving the ball to feet.

That fairly simple move gave him 10 yards of space away from Alvarez, and he was able to thread a good ball through to Gusto, who crossed for a good chance for Nicolas Jackson.

Something similar happened in the second half — this time, Alvarez was slow to close down his opponent, Palmer nutmegged him smoothly and ended up in a brilliant position between the lines. Again, he played in Gusto, who created another fine chance, this time for Raheem Sterling.

A proper defensive midfielder probably wouldn’t have been beaten so easily in these situations — but that is the price you pay when you’re essentially fielding a striker in midfield. Using Alvarez and De Bruyne together as ‘free eights’ feels like a huge risk defensively against dangerous opposition, and it’s also not really the right balance in terms of controlling possession either. It wasn’t a huge surprise that Bernardo Silva, deemed not quite fit enough to start against Chelsea at the weekend, was brought back for Tuesday night’s clash with Brentford, with De Bruyne rested as a precaution against injury.

So what’s going on here? On one hand, you could just consider this part of the move towards fielding midfielders as unconventional forwards — almost every Manchester City midfielder had a go up top the season before Haaland’s arrival. But it feels more like the opposite. Ilkay Gundogan was a midfielder pushed up front, but Alvarez, Gakpo and Havertz — in that order — feel more like attackers dropped back into midfield. The fact that Gakpo and Havertz are 6ft 4in (193cm) furthers the sense that they have the physical build to play as a ‘proper’ centre-forward.

Alvarez and Gakpo at the 2022 World Cup (Dan Mullan/Getty Images)

It’s partly about versatility. Although really it’s more about universality: the job description of a No 8 and No 9 is no longer as separate as it was even five years ago. It involves pressing, linking play, and chipping in with 10-15 goals a season. The shift towards teams forming a five-man attack in the possession phase means those types of players are positioned closer together than previously.

It’s also about the absence of a No 10 role in most top sides. For decades, there has been discussion about the ‘death of the No 10’, which has ranged between the death of the spirit of the No 10, who was traditionally free from defensive responsibilities and allowed to express themselves, and the death of the literal position, which basically required a 4-3-1-2, 3-4-1-2 or 4-2-3-1 formation. At the moment, with the three title contenders generally favouring more of a 4-3-3 than a 4-2-3-1 (although there are elements of both at times), there is no one playing as a No 10, or a withdrawn striker. So whereas Wayne Rooney, for example, spent his peak years alternating between a No 9 and a No 10, now his options at a title contender would be No 9 or a No 8.

That’s the situation facing Havertz, who said, “My best position is as a No 10,” upon his arrival at Chelsea in 2020, and then when moving to Arsenal last summer, said. “Last year I was more a No 9, but I am used to this midfield position because I played there from a young age and now it’s time to just get all the movements back into my brain and hopefully it will be good on the pitch. Maybe having a settled position will be good for me, let’s see.”

But his position has been no more settled at Arsenal — and as the above graphic shows, he is a No 10 being forced to adjust to both a No 8 and a No 9 role, which isn’t easy.

Looking back through the list of past Premier League winners, perhaps the closest previous instance of this approach came from a manager not generally considered a tactical revolutionary.

When Jose Mourinho won his first Premier League title in 2004-05, he spent much of the campaign rotating between Didier Drogba and Eidur Gudjohnsen up front in his 4-3-3. In the second half of the following season, though, he became bolder, and often deployed Gudjohnsen, a centre-forward offering great guile, as a central midfielder. He and Frank Lampard played ahead of Claude Makelele in a highly attacking XI on paper, even if Chelsea relatively rarely turned on the style and ran up a big scoreline.

Gudjohnsen in midfield action for Chelsea during 2005-06 (Matthew Lewis/Getty Images)

“With the system we play I can play the one frontman role, but I wouldn’t say it’s my best position because I like to be more involved,” Gudjohnsen said at the time. “I like to come and get the ball. And I’m not a natural goalscorer even though I’ve scored goals throughout my career.”

That could certainly apply to Havertz, Gakpo and, to a certain extent, Alvarez, too. Few young footballers think of themselves as natural goalscorers these days, and most prefer a withdrawn role. But with the No 10 role not available, it seems silly to think of them as No 10s. The term 8.5 sounds daft, but it’s the most accurate description of their role.

(Top photos: Getty Images)

Read the full article here