This is the latest in our fortnightly series about the 16 triumphant teams in the European Championship before the 17th edition is played in Germany this summer.

So far, we’ve looked at the Soviet Union in 1960, Spain in 1964, Italy in 1968, West Germany in 1972, Czechoslovakia in 1976, West Germany again in 1980, France in 1984, the Netherlands in 1988 and Denmark in 1992. This week — look away England fans — it’s Germany winning Euro 96.

Introduction

Coming into this tournament, only Germany had won more than one European Championship — albeit when competing as West Germany. Here, the pre-tournament favourites made it three, and left England still searching for their first Euros success.

The reality of Euro ’96 doesn’t quite match the perception of the tournament in England — the expansion to 16 teams wasn’t a major success initially, the football was largely defensive and there were a huge number of empty seats at many games, even in the knockout stage. No-one seems to remember this Germany side particularly fondly — but this team deserves more credit for their triumph.

Manager

Berti Vogts always seemed destined to become Germany manager. A one-club man who played over 500 times in defence for Borussia Monchengladbach and won 96 caps for West Germany, including winning Euro 72 and World Cup 1974, upon his retirement he became Germany’s under-21 manager, then the national side’s assistant manager. After Franz Beckenbauer stepped down in 1990, Vogts was his obvious successor.

Vogts has a mixed reputation, having been eliminated twice from World Cups at the quarter-final stage. On paper that’s not disastrous, but it was a major comedown after West Germany had reached three straight finals beforehand, and when the reunification of the country had prompted Beckenbauer to predict the side would be “unbeatable” for years. Vogts achieved little of note afterwards, barely ever working in club football, and oversaw a terrible period for the Scotland national side.

But at Euro ’96 he deserves credit for his management. Off the pitch, he kept egos in check and resisted calls to bring back Lothar Matthaus (who would, improbably, reappear at Euro 2000 at the age of 39). Other volatile players like Bodo Illgner and Stefan Effenburg were also overlooked. On the pitch, he devised a system that suited his players, and he coped well with a succession of selection problems because of injury and suspension. He had emphasised the importance of pressing coming into this tournament, a concept few other sides carried out with much cohesion.

Berti Vogts led Germany to victory at Euro ’96 (Alexander Hassenstein/Bongarts/Getty Images)

Key player

Dresden-born Matthias Sammer captained East Germany in their final match in September 1990, and would have been familiar to viewers of Euro ’92 as a talented midfielder with an eye for goal. He made a big move to Serie A on the basis of his performances at that tournament, but after a disappointing half-season with Inter Milan in 1992-93, he returned to the Bundesliga with Borussia Dortmund. Ten goals in 17 games underlined his attack-minded role.

But then, in keeping with many other key figures in German football history — including Beckenbauer and Matthaus — Sammer was converted from a midfielder into a sweeper, which turned him from a good player into a great player, winning two Bundesliga titles and captaining Dortmund to the European Cup in 1997.

Sammer was magnificent throughout this tournament, using his free role to sweep up behind Germany’s other defenders, always seeming to arrive at the right time to nick the ball away from opposition forwards. He also used his freedom to push forward into attack, popping up with the opener against Russia in the group stage. Then, in the 2-1 victory over Croatia in the quarter-final, his runs into the box brought both goals — first forcing a handball for a penalty despatched by Jurgen Klinsmann, then later having a headed effort blocked, and tucking home the rebound himself.

Sammer scoring against Croatia at Old Trafford (Clive Mason/Allsport via Getty Images)

Sammer wasn’t faultless. He was partly culpable for the concession against Croatia, and he conceded the penalty in the final against Czech Republic when bringing down Karel Poborsky. The foul clearly took place outside the penalty box, but if the referee had awarded a free-kick, he would probably have had to dismiss Sammer. That would have put him alongside Roberto Baggio in 1994, Ronaldo in 1998, Oliver Kahn in 2002 and Zinedine Zidane in 2006 as players who were arguably the best at a tournament, but ended it as the fall guy.

But Sammer stayed on, and he won both the player of the tournament award and the 1996 Ballon d’Or, pipping Ronaldo by a single point. Only he, Beckenbauer and Fabio Cannavaro have won the Ballon d’Or as a defender, although like Der Kaiser, Sammer was so much more than a mere defender.

Tactics

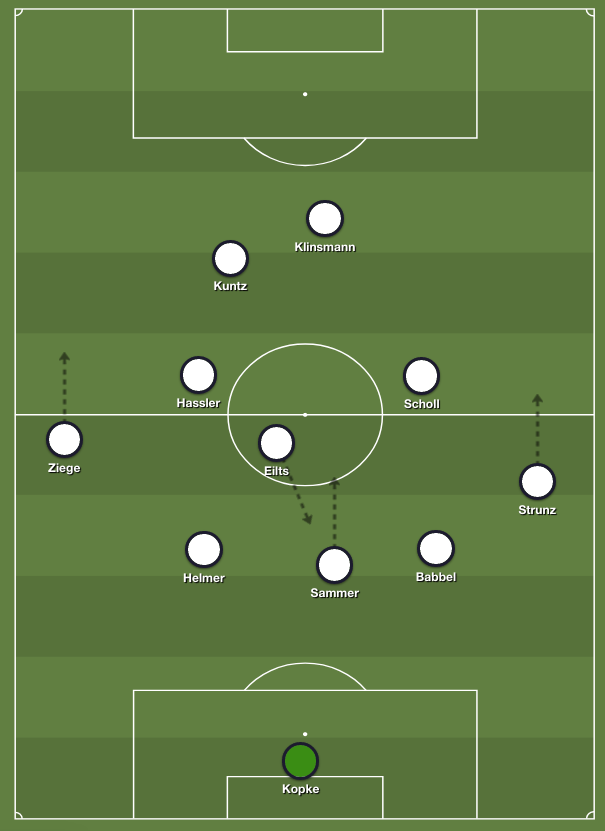

In basic terms it was a 3-5-2, in keeping with previous German winners of this tournament, but Vogts’ system was admirably technical, if a little disjointed at times. After all, this was a side featuring an attack-minded, creative sweeper in conjunction with two hugely talented playmakers, Andreas Moller and Thomas Hassler. The hard-working Dieter Eilts had lots of responsibility in the holding role, often dropping back to cover for Sammer’s bursts into attack, and was Germany’s second-best performer at the tournament.

The precise nature of the system changed regularly because the individuals changed regularly. Ahead of the second, third, fourth and sixth games Vogts made three changes. Ahead of the semi-final against England he made only two — but also changed Germany’s system, using only one striker, introducing holding midfielder Stefan Freund and playing more of a 3-5-1-1. This was because Vogts correctly suspected that England would bring back Paul Ince in place of the suspended Gary Neville, effectively beefing up their midfield, and felt compelled to match the tournament hosts in the centre.

Vogts’ changes were partly because of injuries and suspensions. But they were also because he wanted to vary his side, particularly in attack, and keep opponents guessing. He used classic No 9 Fredi Bobic and left-footed veteran Stefan Kuntz up front in the opening 2-0 win over Czech Republic, then switched completely to Jurgen Klinsmann and Oliver Bierhoff for the 3-0 win over Russia, then went for Klinsmann and Bobic in the next two games, then used Kuntz alone up front against England, before going for Kuntz and Klinsmann for the first time in the final.

Again, many of these changes were enforced, but it’s difficult to think of another major tournament winner whose starting XI changed so regularly.

You might be surprised to learn…

Germany faced such a selection crisis ahead of the final that, in an unprecedented move, they were given special dispensation to add two players to their squad. They’d already made the extent of their problems clear by publicising the fact they’d printed outfield shirts for back-up goalkeepers Oliver Kahn and Oliver Reck, ahead of the semi-final against England.

“Germany’s problem is that five players are definitely out,” read a UEFA statement. “Jurgen Kohler, Mario Basler and Fredi Bobic have suffered long-term injuries and Stefan Reuter and Andreas Moller are suspended.” It seemed an odd justification — injuries are one thing, but Germany being without two first-teamers because of suspension owed to the players’ ill discipline, which surely shouldn’t necessitate allowing Vogts to expand his 22-man squad. The Czech side were also handed the opportunity to select an additional player, to make things fair, but declined the offer.

In the end, Vogts picked only one extra player: holding midfielder Jens Todt, who flew to England especially for the final and then, amid criticism of UEFA’s decision, wasn’t even named in the matchday squad.

Andreas Moller was booked against England in the semi-final and missed the final (Shaun Botterill/Allsport via Getty Images)

The final

The Czech Republic were not among the favourites coming into the tournament and, had they won this final, it would arguably have been even more of a surprise than Denmark’s triumph four years beforehand.

The final started cautiously and then opened up significantly after the break, partly because the outstanding Eilts became yet another injury victim and was replaced by wing-back Marco Bode, which meant Christian Ziege moving inside into a somewhat unfamiliar central midfield role. He lacked Eilts’ positional sense, but offered more forward running and was probably the best player in the final.

The Czechs, without question the neutrals’ favourites, went ahead from a powerful Patrik Berger penalty, after the aforementioned Sammer foul on Poborsky — the German sweeper seemed to have more problems against the speed of the Czechs than against any other side at the tournament. Poborsky, in particular, played well from the right flank although, in keeping with his team-mates, he became somewhat subdued after the opener.

Berger gave Czech Republic the lead (Lutz Bongarts/Bongarts/Getty Images)

Substitutes proved vital — Vladimir Smicer was the Czechs’ only change and nearly scored late on, but Germany’s reserves were more decisive.

The decisive moment

The hero in the final was Bierhoff, which was something of a surprise considering he hadn’t featured regularly beforehand and was relatively unknown in his homeland, having spent the previous five years playing in Italy — three of them in Serie B. He’d only made his national debut four months before this tournament, scoring twice against Denmark. But Bierhoff was the classic Plan B, the definition of a target man, and far more dangerous with his head than he was with his feet. When Germany became a little desperate, he was a perfect supersub and, in the final, was introduced for playmaker Mehmet Scholl as Germany went more direct. It took only four minutes for him to equalise, with a classic downward header from Ziege’s inswinging free-kick.

But Bierhoff wasn’t finished yet. The extra-time winner was a horribly scruffy goal that started with a long ball for Bierhoff’s flick-on to Klinsmann, who chipped it back towards him. Bierhoff then did well to use his frame to shield the ball, turn a defender and then lash a left-footed shot towards goal, but he was helped significantly by a minor deflection and then Petr Kouba’s fumble which send the ball spinning agonisingly in off the post. The Czechs complained that Kuntz, who watched the ball trickle over the line, was in an offside position and interfered with Kouba’s attempted save. But the goal stood.

Bierhoff celebrates the golden goal (Clive Mason/Allsport/Getty Images/Hulton Archive)

And that was that. For the first time, a major international tournament had been settled by a golden goal. The playground concept of ‘next goal wins’ had come to the highest level. This was the seventh knockout game in this tournament — five of those games had gone to extra time, yet this was the first golden goal. The concept seemed to encourage negative football, with both sides afraid of making a mistake. Sure enough, Kouba’s mistake cost the Czech Republic.

Were they the best side?

As tough as it is for an Englishman to admit this, they probably were.

In the group stage, Germany topped what is statistically the deathliest group of death ever (based upon FIFA rankings at the time) ahead of Czech Republic, Italy and Russia — without conceding a goal. They confidently defeated an overly physical Croatia side in the quarter-final, and while both sides could have won a highly eventful semi-final which went to penalties, prevailing over England at Wembley amid the Three Lions fever of 1996 was seriously impressive, especially with such injury problems.

In the host nation, of course, the sense was that England had been robbed. But realistically England played well throughout in only one match — the 4-1 thrashing of the Netherlands was the best performance of the tournament — and a quick 10-minute burst in a famous 2-0 win over Scotland.

In truth, this wasn’t a tournament of great football, and featured a pitiful 2.06 goals per game. Germany were inevitably cast as the party poopers but they were a fitting winner in a tournament which wasn’t about spectacular football, and was far more about simply getting the job done. Sides like France, Croatia, Italy and the Netherlands were all accused, at various points, of complacency — something you would never level at this German side.

(Top photo: Getty Images)

Read the full article here