It was in the autumn of 2017 when goal kicks first started to become viewed as a legitimate attacking instrument.

After signing from Benfica, it soon became clear that the left leg of Manchester City goalkeeper Ederson was more of a trebuchet than a human limb, capable of striking the ball 80 yards over the top of the opposition defence to set up goals.

The ploy befuddled teams, as it was something that had not been seen before. City’s entire front three would position themselves 20 yards beyond the opposition back line, safe in the knowledge they could not be offside from a goal kick.

This set-up from a City goal kick is great. Players stretched out all over the place, the opposition have no idea whether the pass is going to go short, into the big hole in the middle, or straight up top. Ederson really has changed the game. pic.twitter.com/hhzQBJuJP1

— Sam Lee (@SamLee) April 28, 2019

There are an average of 16 goal kicks in a Premier League match, which makes the scenario the third-most-common set piece behind throw-ins and free kicks.

Until 2017, however, presumably because geographically in terms of the pitch they start just about as far from the opposition net as possible, goal kicks had largely been performed off the cuff and without much thought, seen as nothing more than a requirement to restart play rather than a set piece that could be mapped out and used against your opponent.

On most occasions, teams pushed everyone up and the goalkeeper smashed the ball as far as he could, an act in English football widely soundtracked by fans behind his goal shouting, “Oooooooooooh…! You’re s**t! Ahhhhhhhhhhhhh!” — originally as an attempt to distract the goalkeeper involved, later as a form of pantomime to amuse themselves.

For decade after decade, goal kicks were invariably hit long and with little strategic thought (Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty)

Then, in summer 2019, IFAB — the body responsible for the laws of the game — changed the one around goal kicks to state that the ball no longer had to exit the penalty area of the team taking it before a player could receive the first pass.

Football has fiddled with the offside rule and VAR has transformed the spectacle, particularly for those attending games, but the change to the goal-kick rule is the most radical change to the style of the sport since the one banning goalkeepers from picking up backpasses was introduced in the early 1990s.

There were some immediate, albeit expected, changes in behaviour now that the first pass was free to be controlled anywhere inside the penalty area. The number of goal kicks in the Premier League played short has steadily risen and is now more than double the figure in 2018-19, when around three-quarters of them were walloped upfield.

An additional area measuring 44 yards by 18 yards in which to receive the ball may not seem transformative, but in the past five years it has played a significant role in hastening the rise of man-to-man marking, the hollowing out of central midfield and the tactic of playing over the opposition press.

These are three of the themes that UEFA’s technical observer tactical review highlighted from this summer’s European Championship, epitomised by Slovakia luring England into a full press and almost scoring via direct play up to their striker, and the Netherlands creating an overload in the middle of the pitch against high-pressing Austria.

Slovakia almost score from a goal kick against England

The Dutch create a four-v-two in midfield and counter-attack on Austria

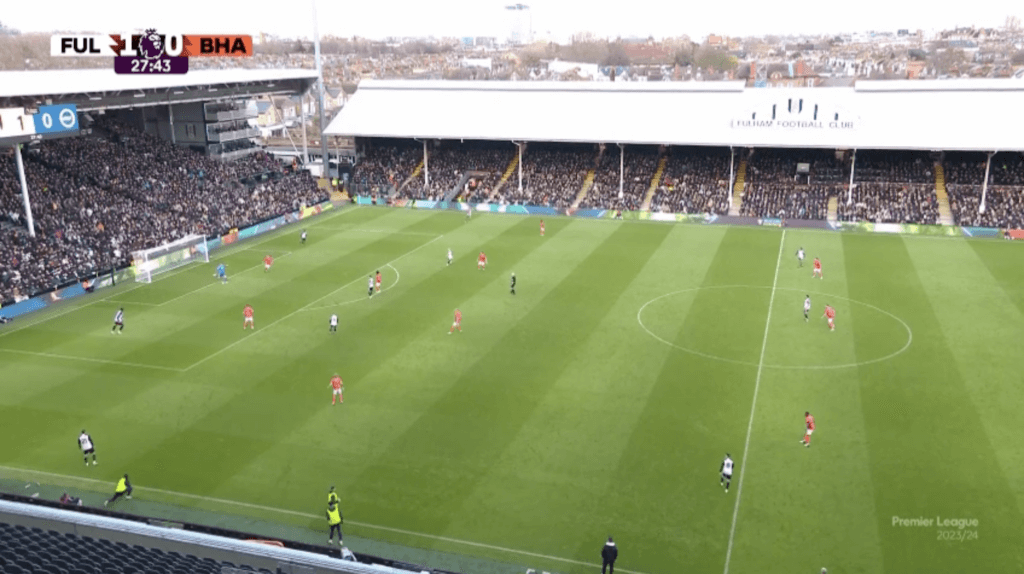

It is why the scenarios below — one cluster of players around the penalty area of the team taking the goal kick, another just inside the opposition half and a sea of nothingness in between — have become a common sight across all top leagues.

Tactical camera view of Brighton vs Chelsea

Tactical camera view of Fulham vs Brighton

Man City vs Luton in the FA Cup last season, in which Ederson’s long kicking ability played a pivotal part in several goals

‘The impact of the rule change was underestimated by many,” said Arsene Wenger, the former Arsenal manager who is now chief of global development for FIFA, world football’s governing body, in a review of the rule last year.

“It was introduced to make the game faster and more spectacular, but even more has changed. The main attraction is to attract your opponent as far away from goal as you can, and try to play through. If you can play through the first pressure, you have a whole half of the pitch to be dangerous. That is what is at stake from the start.”

But how does a trend like this start to proliferate in such a quick space of time? And how has it become just as normal to see a centre-back passing the ball to their goalkeeper as the other way around?

It is something Arsenal regularly do, with defender Gabriel playing to ’keeper David Raya before the latter punts long towards Kai Havertz up front and the midfield cavalry race forward on supporting runs.

“What initially happened after the rule change was that it made it easier to build up, as you weren’t having to play this long pass across the box, which gave the pressing team the chance to get there early,” says one first-team coach/analyst at a major European club, quoted anonymously here as they did not have permission to speak.

“Back then, if the goalkeeper played it to a centre-back, you had locked yourself down to one side of the pitch, whereas now if the defender plays to the goalkeeper, you are dead-centre.

“Most teams bring midfielders to the box now and it just makes the space much bigger to defend. It is so hard to be compact as, if you want to get pressure on at the top end, the midfielders are having to match midfielders, which naturally opens up space behind them.

“The question you are asking the opposition is, ‘Are you so keen to get pressure on us that you are going to leave yourself three-v-three or four-v-four at the back?’ Teams realised they had to commit more bodies to force it long, which explains the rise of man-to-man pressing.”

(Alex Pantling/Getty Images)

Every action brings a reaction, however, and that is what has happened, with teams realising they can manufacture false transition moments by isolating their forwards.

“The attacking team’s response has been, ‘If you are going to release six or seven players into the final quarter of the pitch, we’ll get a goalkeeper who can put it over the top of your defence’,” the same coach/analyst says. “There is no space between the lines now to be static and turn on the ball. The concept has changed to become about leaving the big spaces you want to be free and then arriving there at the right moment, so you can run and your marker has to react to it.”

One of the most effective teams in the first few seasons after the rule change were Italy’s Inter Milan, under Antonio Conte. As a coach whose preferred brand of football is about rehearsed patterns of play, Conte took advantage by manipulating the opposition’s setup to leave his attackers with space to run into.

More recently, Germany’s national team have been creative in their use of goal kicks, and in their March friendlies this year they showed us how many different layers are involved in the thinking.

In this example against the Netherlands, goalkeeper Manuel Neuer edges forward with the ball while his midfielders move out from the centre to drag their markers wide and open up a central passing channel to Havertz. The ball from Neuer is the trigger for the supporting cast to coalesce around him, with Havertz’s lay-off springing a four-v-four opportunity.

The new rule gave coaches a blank canvas to go to work on, and has produced many variations in how to try to gain an advantage in build-up.

Southampton manager Russell Martin has been one of the head coaches who has sought to rethink the setup.

One centre-back drops in line with the goalkeeper, receives, and then waits on the opposition striker pressing him before playing a return ball to the ’keeper, who had pushed up 10 yards so he could be used as the spare man, just like another centre-back.

Leading French club Marseille’s new head coach Roberto De Zerbi was bold in subscribing to almost exclusively short goal kicks in his previous job at Brighton & Hove Albion of the Premier League but he was even more experimental in the two clubs before that at Sassuolo in Italy and Ukraine’s Shakhtar Donetsk.

In his 2020-21 debut season with the latter, he regularly had his team play out with four players inside their penalty box, drawing the press in before finding the spare man after they had lured the opposition players to one side.

Last season, Hamburg-based St Pauli, whose manager Fabian Hurzeler has succeeded De Zerbi at Brighton, attempted various high-stakes routines on their way to promotion from the German second division, but the one common theme was their motivation to have their goalkeeper advance with the ball after receiving from a defender.

This meant his long kicks went even nearer to the opposition goal, with the team higher up the pitch when contesting any resulting second balls.

All of these teams vary their approach, as does new Liverpool head coach Arne Slot.

When his Feyenoord team played short with the intention of cutting through the press, however, they did it in a much bolder way than most.

Here, against NEC Nijmegen in the Dutch top flight earlier this year, Feyenoord have goalkeeper Justin Bijlow stand still with the ball and delay his pass until the very last moment, and centre-back Thomas Beelen is trusted to dribble across his own penalty area and wait for a space to present itself.

This is a more freehand approach, but there are clear risks that come with playing like this inside your own penalty area — as many teams have found out in the past five years. Which explains why setting the bait with a pass to the goalkeeper and then going long has become the go-to strategy for most top teams.

Football underwent a significant change five years ago and we are only starting to understand how much tactical variety has been made possible.

(Top photo: Jacques Feeney/Offside/Offside via Getty Images)

Read the full article here