A striking thing about the reaction to England’s group-stage performance is how many different solutions have been offered.

In midfield, it’s possible to find pundits who think the answer is Kobbie Mainoo, or Adam Wharton, or dropping Jude Bellingham deep into that role. Some like Conor Gallagher’s energy and others thought the Trent Alexander-Arnold experiment worked reasonably well.

Some thought Phil Foden should move inside to become the No 10, but others suggested he should be dropped altogether (he has now temporarily returned home ahead of the birth of his third child.) Bukayo Saka has been England’s brightest player down the right, but there have been columns about how he should move to left wing or even left-back. Some believe Cole Palmer, bright as a substitute against Slovenia, deserves a start. And some even want Harry Kane, England’s captain and record goalscorer, dropped with Ollie Watkins coming in to stretch the opposition. Oh, and what about a back three and wing-backs?

Harry Kane leads the line (Stu Forster/Getty Images)

The plethora of different views suggests a few things: a) Gareth Southgate almost has too many options in terms of appeasing the public, b) there is no obvious answer to England lack of balance, and c) more than anything else, England have been so bad that almost nothing about the side, perhaps with the exception of the centre-back pairing, is considered to have worked well.

But while international sides sometimes suddenly gel in the knockout stage, England have been so wretched in possession that it’s difficult to imagine Southgate miraculously finding a magic formula. He might, in fact, decide that the best approach is continuity.

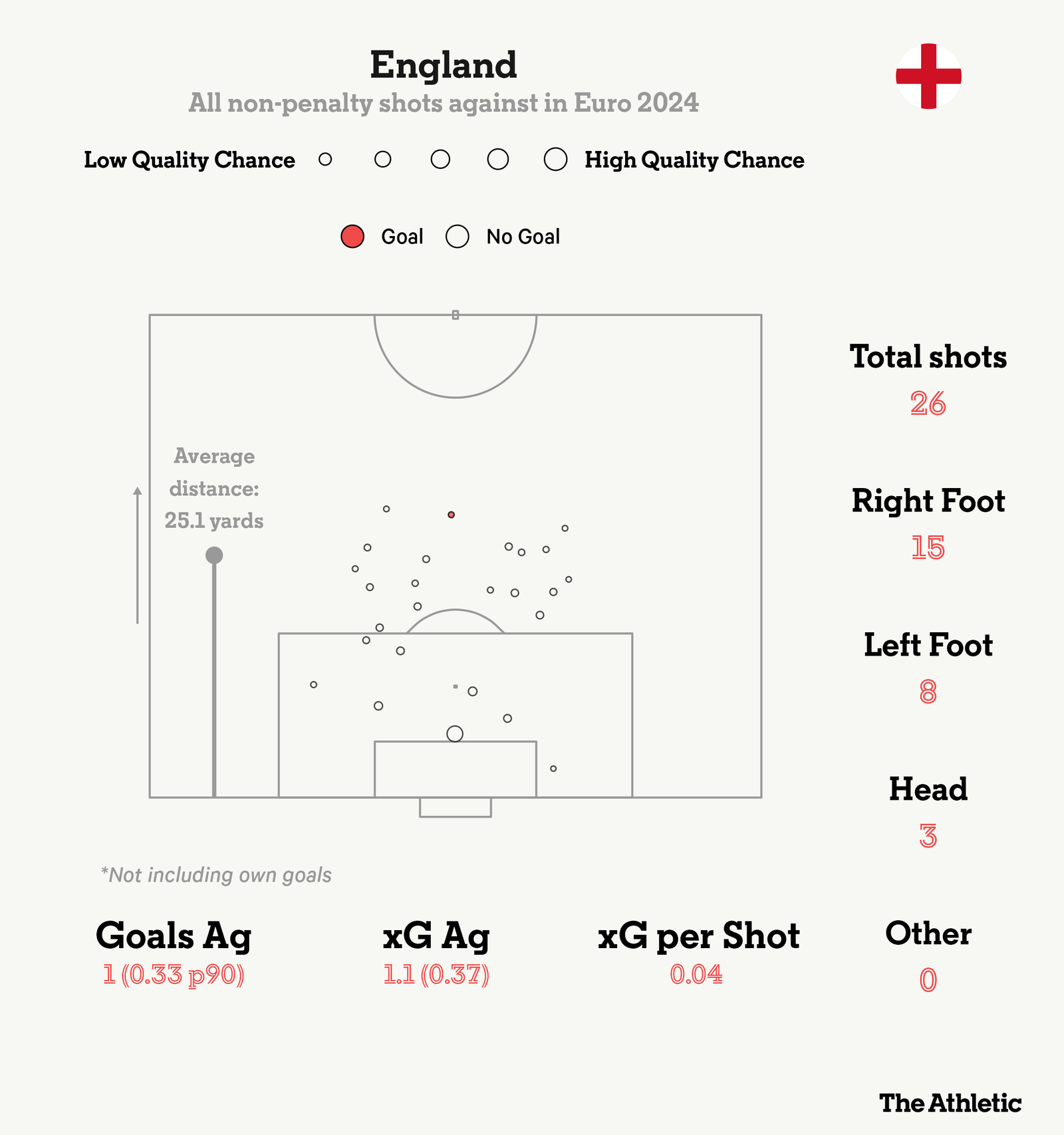

After all, at the end of the group stage, England have yet to allow the opposition a single clear-cut chance from open play. They have conceded only once. Spain have a superior defensive record, having kept three clean sheets from three games. But in expected goals terms, they’ve conceded 2.7. England’s is 1.1, the lowest in the competition. They’ve only been beaten by Morten Hjulmand’s excellent long-range strike, which flew in off the post in the 1-1 draw with Denmark.

Defences, rather than attacks, tend to win tournaments, and England have actually been very solid. Yes, that’s partly due to the lack of serious contenders they’ve faced thus far, but in terms of the FIFA rankings, England’s group was middling rather than the weakest in the competition. In Aleksandar Mitrovic, Rasmus Hojlund and Benjamin Sesko, England have nullified good centre-forwards.

This shot map shows the opposition attempts at goal. The only serious chance has been an Andreas Christensen header from a corner, five minutes from the end of the draw in Frankfurt.

The defenders themselves can take credit. Kieran Trippier endured a difficult season for Newcastle on the right, and is plainly not comfortable overlapping down the left, but he’s rarely been exposed. It shouldn’t be forgotten that both Serbia and Denmark played a striker — Dusan Vlahovic and Jonas Wind — dropping to the right flank without possession, perhaps hoping to target Trippier with the power of a proper centre-forward, but he has stood strong.

In the middle, Marc Guehi has proved a fine partner for John Stones, even if there’s a worry that he was excellent in the first game, good in the second and more nervy in the third. On the right, Kyle Walker is sometimes mocked because of his reliance on ‘recovery pace’, but it is constantly a very useful attribute. It’s difficult to judge Jordan Pickford too much, because he hasn’t been tested, although in keeping with others in his position, he has been too keen to parry or punch, seemingly worried by the lack of grip on the Euro 2024 ball.

Marc Guehi has been solid in his first tournament (Matthias Hangst/Getty Images)

But defending is about working as a unit and, by and large, England have done that well. The biggest concern was against Denmark, when Phil Foden abandoned the left flank too readily and let Joachim Maehle run at Trippier.

Otherwise, the shape has been good. Declan Rice is more than a holding midfielder at club level, but Southgate’s decision to permanently employ him as the deepest player has created a consistent feel to England’s base — it would be more damaging if Rice was deployed as a No 8 and England had chopped and changed in that role in front of the defence. Gallagher is limited in possession but does look more comfortable in a defensive sense than Alexander-Arnold. Bellingham is a defensively capable No 10, and Saka has always been responsible without possession — hence the belief that he could reasonably switched to left-back.

The alternatives are more defensively risky. Palmer, for example, had a sensational first season for Chelsea but his lack of work without the ball sometimes caused problems. Saka hasn’t played at full-back for a long time. Mainoo plays for a club side who were constantly open between the lines, so it’s difficult to ascertain his defensive qualities. England might be best off just accepting their lot — not creating much, not conceding much, and hoping for a moment of magic from players like Foden, Bellingham, Saka and Kane, all of whom are very much capable of providing that.

Pickford has only conceded once at Euro 2024 (Matthias Hangst/Getty Images)

It is, of course, depressing that England are being spoken about this, and perhaps it’s defeatist to suggest there’s little chance of a significant attacking improvement. But the collective concepts the supporters yearn for — interplay and movement in the final third, aggressive pressing high up — take time to perfect. If Southgate can’t get England doing that after nearly eight years, with this collection of players, it seems unlikely that a few more days on the training ground might click things into place.

And therefore England might be best off with their current approach. Keep clean sheets, nick a scrappy goal from somewhere and hope to progress deep in the competition with 1-0s.

England’s best chance of victory, it seems, is being Greece 2004 rather than Spain 2008.

(Header photo: Richard Pelham/Getty Images)

Read the full article here