When the playing career of Liverpool’s new head coach Arne Slot ended 11 summers ago, he went to the directors at PEC Zwolle – one of the less illustrious clubs of the Dutch top flight – and told them he wanted to work at the highest level possible.

Instead, he was dispatched to the under-14 team, where the footballers he inherited, including Max Leeflang, saw him as a character from the FIFA video game.

“At the beginning he was so… how do you say it? Calm,” recalls Leeflang, who is now 23. “But when you went onto the pitch, he wanted you to do everything good and when you made a mistake, you heard it every time — from the first training until the last.

“If you play one bad ball, he stopped the session and would say, ‘Next one has to be good’. You’d think, ‘Come on, it’s only one bad ball, just one mistake…’. It is only when you are older you realise that these are the standards and the coach is so good.”

Before Slot’s appointment, and for several months after, Zwolle’s results were, as Leeflang puts it, “very, very bad”, including 9-1 and 6-0 defeats to Ajax and AZ Alkmaar. It remains Leeflang’s view that for a period, Zwolle’s under-14s were “the worst team I have ever played in”, though that wasn’t Slot’s fault. The team had been shredded before his arrival and Leeflang was one of nine signings.

Even so, in the first half of Slot’s first season in charge, Zwolle’s under-14s won only once.

“But then we started winning. Then again, again, and again. Suddenly everyone was talking about us, ‘How is this possible? The players are so bad…’. The difference was Arne Slot. It was unbelievable.”

Max Leeflang, a youth-team player under Slot, credits him as the best coach he has worked with (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

Zwolle’s players would train for an hour and a half every morning from 8.30am until 10am. They would then go to school at the Centre for Sports and Education, across the road from Zwolle’s ground. Under Slot, from 3pm, there was usually an analysis of the training session earlier that day.

Such reflection was initially alien to Leeflang and his young team-mates, but Slot saw it as essential. Later, at Feyenoord, where video analysis had existed for eight years, he became the first head coach to communicate directly with the drone pilot who was filming the sessions. In Rotterdam, everything under Slot’s direction was recorded.

“Before Arne, there was no video work at Zwolle,” Leeflang says. “I had never seen it. For everyone, it was new. I would ask myself, ‘Why are we doing this?’. It was weird. But then we’d see the results and realise that maybe it has helped.”

Leeflang became Slot’s captain. As a central defender, there were some instructions he did not expect. “You are usually asked to hold your position but Arne would want me to dribble forward with it. As soon as the striker approached, I would then have to play the ball and move, creating another angle. He wanted you to invite pressure from the opponent because that pulls the player out of position and creates space for you to play in.

“He would always say, ‘Don’t play the ball back, always play forward’. Every session was competitive. It was done in games: three versus three, three versus two, two against two. Entire training sessions on possession. He wanted intensity and players to feel the pressure of the opponent.”

In the Dutch tradition, Zwolle’s under 14s would usually set up in a 4-3-3 formation. Yet Slot “always wanted a fourth player in the midfield”. This would lead to the right-back or the right central defender pushing up into the middle of the pitch. “At the time, the right-back at the elite clubs would play high and wide but Arne was ahead of other coaches in his thinking,” Leeflang says.

Leeflang quickly came to appreciate what Slot wanted but other boys found it harder. “His level was too high for the players we had. Some of the players couldn’t understand what he wanted. For him, it must have been hard. He basically wanted the youth system to train as professionally as the first team.”

Zwolle’s teenagers, however, knew that football was not everything to Slot. “School was very important,” says Leeflang. “If you did bad at school, then you couldn’t train. In one session, we had just eight players on the pitch because so many boys had been bad at school. It didn’t matter to Arne. Discipline came first. He realised not many of these players would become footballers, so they had to work hard at their education.”

One player, as Leeflang puts it, was “quite fat”. Slot tried to help him lose a few pounds by asking him to do laps of the pitch before each training session. Every Friday, the players would have a weigh-in and if anyone was heavier than the week before, they would not be allowed to play at the weekend. Leeflang says that after Slot left the club, the “fat” player put weight on and fell away from the scene.

Leeflang, who remained at Zwolle until he was 19 before he joined Go Ahead Eagles, says Slot made him interested in coaching. He later took charge of the under-nines at a club called Berkum Youth, where one of his players was Slot’s son Juup. This led to Slot — now amid his own professional journey away from Zwolle at Cambuur, where he was the first team’s assistant manager, and then AZ — helping out as the assistant to Leeflang.

Leeflang now works as a sports teacher in Utrecht and plays part-time in the Dutch third division with VVOG Harderwijk, where he has transitioned into a No 10.

“When I was 14, my dad used to say, ‘Listen to Arne, he’s so good’, and I used to say, ‘Nah, there are so many good trainers…’. Now I realise I was very wrong. He was the best.

“After he moved on to Cambuur, I used to think, ‘Arne, please come back…’. I have had other coaches with long professional careers behind them. They have played 500 matches but Arne was way better than them. The difference was so big.”

Liverpool have appointed Arne Slot as their new head coach — and The Athletic has every angle covered.

In the Netherlands, Slot is associated with Rotterdam because of his achievements at Feyenoord, where in 2023 he lifted the Eredivisie title. Yet it is in Zwolle where he started his coaching career and had two spells as a player, and where his wife, son and daughter still live.

Jan Everse was appointed as Zwolle’s manager in 1996, after Slot had made his debut for the club as an 18-year-old. Everse, capped twice by the Netherlands in 1975, was born in Rotterdam, where he played for Feyenoord, before taking the bold step of joining biggest rivals Ajax, where he was forced to retire at 26 because of the same ankle injury that ruined the career of the legendary Marco van Basten.

This forced him into coaching. Everse was heavily influenced by Tomislav Ivic, his trainer at Ajax, whose sessions on positional play were repetitive but effective. Sixteen years later, Everse arrived at Zwolle and in Slot, he could see a “technical player with a good vision of the game. He knew his surroundings”.

“He was always convinced of his own qualities,” Everse adds. “He never doubted — that’s good, because if you don’t believe in yourself, you will never succeed.”

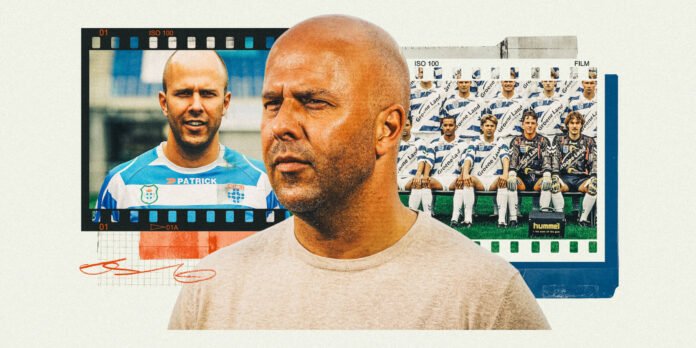

Arne Slot (circled) with the FC Zwolle squad in July 1996 (VI Images via Getty Images)

Yet Slot’s professional debut before Everse’s arrival came in a team that would finish in 15th place in the Dutch second division, one that needed ripping up. “They were rubbish, the football was so bad,” says Everse.

When Slot got injured in pre-season, the coach had to plan for the campaign without him. “Arne could not understand why he was not playing. He was telling people he would return to the team when he was fit,” Everse says.

Except, it took nearly 18 months for Slot to establish himself in Zwolle’s starting XI.

“Sometimes he would get 20 or 30 minutes. He was very curious about why he was not playing. I would say to him: ‘Arne, you are my best player. But the problem is, every time you play, the opponent is also the best player from the other team. I cannot afford that. When we lose the ball, you do nothing. We cannot rely on our qualities when we have the ball. It’s not enough in modern football.

“‘You have to do more. You have to put pressure on the ball. You have to defend. You have to attack. You are a very good passer but if you only touch the ball 15 times in a game, you do not have a value for my team’.”

Jan Everse managed Slot at Zwolle (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

Robert Maaskant was Everse’s assistant. Slot would go to him as well, asking why he wasn’t involved as much as he would like, and Maaskant would give him the same message. These conversations happened several times.

Steadily, Slot began to understand. Everse wanted him to sprint short distances more often. He calculated that this type of running would result in more touches, possibly as many as 60 per game. And this would increase his chances of scoring and assisting his team-mates. Everse would switch between a 4-3-3 (his preference) and a 4-2-3-1. Slot was best suited as a No 8 or a No 10.

“It was my aim to create triangles. A 4-3-3 creates the best opportunity for that because the distance between the players is smaller if you get it right. This makes passing easier, and Arne was an excellent passer.”

Everse remembers seeing the change in his game, and the day he told him that he would finally be back in the team. “I said to him: ‘Tomorrow, Arne, you will start and I am confident you will play well. You are now the player I want. You are fit. You are aggressive’.

“I am not a running coach but sometimes you have to run to put pressure on the ball and create space. Arne was finally running. In one year, I believed Arne would play in the Eredivisie and I was right because he moved to NAC Breda.”

Arne Slot went on to play for NAC Breda (Adam Davy/EMPICS via Getty Images)

This came after Everse left Zwolle for Sparta Rotterdam. A decade later, the pair would work together again for a brief period after Everse returned to Zwolle as coach and Slot rejoined the club on loan.

They have a mutual friend, a journalist, who was told by Slot that Everse had a profound effect on his thinking. At Feyenoord, Everse believes Slot “brought Ajax football to Rotterdam, which is more of a working city.” By that, he means a style that is technical, physical and ruled by professionalism.

“He changed Feyenoord’s mentality by his demands,” Everse says. “Arne is better than me at managing the emotions of the team. Perhaps I was too critical, too cynical. Arne is a diplomat. He is very smart. He always first counts to 10. He is like a priest.”

The Real Jurgen Klopp – an Athletic special series

Slot grew up in Bergentheim, a small village a 40-minute drive east from Zwolle, in the middle of the farmland where the Netherlands blurs into Germany.

The church bells ring every half an hour during the day, and it is common for families to hang a small picture of the Virgin Mary in their bedrooms.

It is conservative, religious and sober, with the only cafe, closed more often than it is open, positioned on its outer fringes, like no one really wants it there.

“I never heard about Bergentheim before Arne,” says Everse. “It might be near the border with Germany but Arne is not a German. He is very Dutch.”

Similarly, Leefling smiles when he is told The Athletic is visiting Bergentheim: “I have only been there once, to play a football match. Before this match, I did not know the place even existed.”

In the nearest German town of Itterbeck, where the residents of Bergentheim only usually visit to get cheaper gas, nobody seems to have heard of Arne Slot. Yet in Bergentheim, the opposite is the case, though he is not exactly a celebrity.

“Very nice guy,” says Roel Veurtlink, the butcher of Bergentheim, which is not as sinister as it sounds, as he mixes macaroni cheese filled with hacks of Dutch ham in a steel tub on the counter of his shop. “He comes back from time to time. Nobody pays attention to him, that’s not who we are.

Roel Veurtlink, a butcher in Bergentheim, knows Slot from his time in the village (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

“People are modest. He stands with both feet on the ground. We make small talk, here in the butchers. His father, the school principal, was always his trainer. He grew up with football. He grew up with the discipline you need to become a footballer. He was very driven. You’d often see him running around the streets, past the window. As a little boy, he knew how it worked.”

The third of three children in a sporty family, Slot also played tennis. Before Zwolle, he represented the amateur football club VV Bergentheim, which has an impressive facility on the edge of the village, across the other side of a canal. It has a grass pitch, with an old stand, as well as a 4G area, where a banner is fixed to some rigging, displaying the message, “Green Beast! Green Pride!”

The place is so small and so quiet, there is little to distinguish the different times of the day. According to people who know Slot better, he would learn a more Burgundy way of life after moving to Breda, close to the Belgian border.

VV Bergentheim’s homely stadium (Simon Hughes/The Athletic)

“He is not thinking as the guy from a small village,” says Everse. “He always thinks big.”

He will relish leading Liverpool and succeeding someone as popular as Jurgen Klopp, according to Everse, who says he is “99.9 per cent certain” Slot will succeed.

“Arne shares some details with Klopp, particularly where they come from. Rural men turned city boys. Klopp did it in Dortmund and Arne did it in Rotterdam: working-class cities, similar to Liverpool.”

(Top photos: Broer van den Boom/BSR Agency/Getty Images; VI Images via Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here