A year or two before I was appointed Newcastle United manager in 2009, my father stopped going to St James’ Park. He loved the club and always had done — one of the lucky few who actually saw the team win a trophy — but he didn’t like it very much when Mike Ashley was the owner. He wasn’t alone in that, of course, because the place was a mess. Chaos. Worse. And he wouldn’t go to matches, he said, not while Mike was there.

Let me explain something fundamental about my dad: that didn’t change, even when I got the job. In my naivety, I assumed he would come to games when it was my (ill-fated) turn to stand by the dugout, but my assumption was misplaced. He said no. He said, “I’ve made my decision and I’m sticking to it.” I could only laugh because it was perfect in its own way. He was stubborn, determined, immovable, principled. And, looking back, he had a point.

I told that story for Dad’s eulogy in May and on a day that felt entirely wrong, that part of it felt right. It was him to a tee. Along with Will, my son, I’d carried his coffin into the crematorium — the hardest thing I’ve ever done — as the Match of the Day theme blared out, jaunty and loud. The music was his decision too, although he pinched that idea from my mam, telling us shortly before he died that this was what he wanted.

He was not a poetic man, my dad — he was as grounded as they come, a bloke’s bloke, a Geordie grafter — but when I was a kid, we’d sat around the telly as a family on Saturday nights watching the football highlights. So how about that for a choker? I got to the end of last season with the blinkers on. I appeared on Match of the Day a couple of times and glided through it, just as I did for my punditry work at the European Championship, but the here and now feels different.

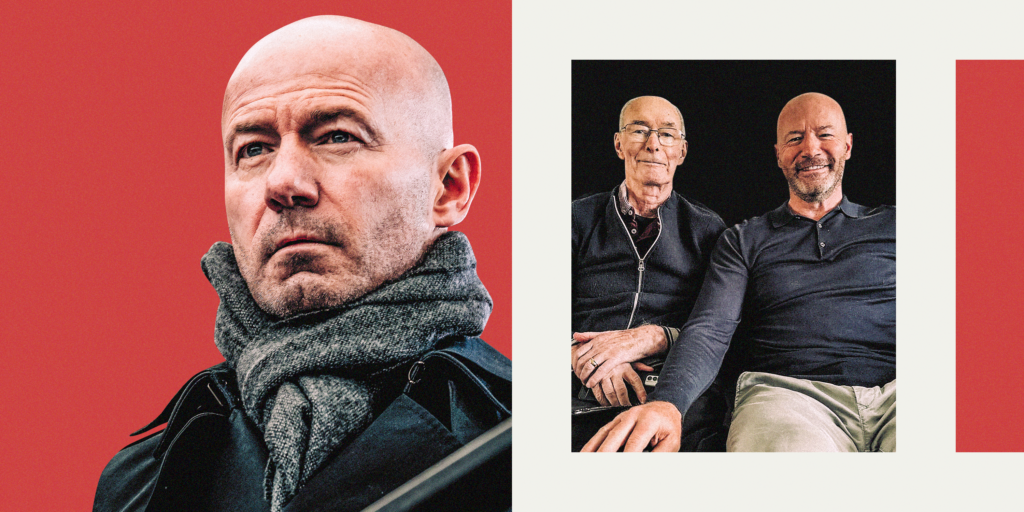

Alan Shearer will be back in the Match of the Day studio this weekend (Alex Pantling/Getty Images)

I’ll be in the BBC studios in Salford this weekend and I honestly can’t tell you how it will feel when that famous tune starts up, but I do know it will be tough — very tough. This won’t come as a total surprise to most of you, but like my dad, I’m not emotional by nature, yet at 54 years old I’m heading into my first season without him beside me, without him just there. It’s a void that can’t be filled and it still feels very raw.

Why am I sharing this? In part, it’s because we don’t often consider the support network behind players and we should celebrate the dedication and sacrifice that makes every career possible. I wouldn’t have been a footballer, wouldn’t have appeared on Match of the Day, and wouldn’t be writing this without my dad. In a specific way I’ll come on to, it feels important. And it’s because, in life, we occasionally leave words unspoken and this is my outlet.

Dad, I miss you and I’m very proud of you.

It’s the early 1970s in Park Avenue, Gosforth, three miles from St James’ and the centre of Newcastle. I’m in the small back garden behind our three-bedroom council house and my dad — also called Alan — is tossing a ball at my feet, feet which barely had the coordination to walk. This was how it began. I wouldn’t say I didn’t have a choice in the matter, but there I was, blonde hair, pot belly, football at my toes, falling in love.

There was never any pressure. Dad didn’t coach me. He hadn’t been a serious footballer himself, albeit he’d played with his mates when he was younger, so it wasn’t in the genes. He just played with me every night when he came home from work. He was a sheet metal worker in Cramlington, which must have been a gruelling, exhausting occupation, but there was never any sign of that in our garden, at our version of St James’, at our Wembley.

By the time I went to school, I was obviously half-decent. My dad — and my mam — now became a taxi service. He would drive me to training at Wallsend Boys Club two or three nights a week and again at weekends. Sometimes he would have a pint when I was training, but mostly he would just watch. I think he realised by that stage that I had a talent, although I wasn’t the only one at Wallsend, which was like a conveyor belt for good players.

Nothing was ever expected of me in those terms. In other ways, it was. I’ve always been fanatical about time-keeping — on time is late and early is on-time and late is unforgivable — and this is something I trace directly back to Dad. He had standards. He believed there was a proper way to behave. He was strict, but never in a physical way. And, as so often happens later, he softened. He doted — absolutely doted — on Will, Hollie and Chloe, my kids.

Both of my parents worked. My mam, Anne, was a home help for the local council, so it was not as if we were poor, but there wasn’t a lot of spare cash flying around. They kept an empty whiskey bottle in the lounge and they would gradually fill it with loose change, which was how they could afford to buy me new football boots or shirts, how they paid for school clothes for Karen, my sister. I’ll never forget them emptying that penny jar. I can see it so clearly.

They continued to help when I left school at 15 and moved to Southampton at the other end of the country. The two of them waved me off at Central Station, the tears rolling down my mam’s cheeks as she said goodbye to her little boy. It wasn’t until my own children reached a similar age that I came to understand how difficult that must have been. I’d watch my lot play sport at school or do anything and just be overwhelmed by fear and stress and love and concern. All those feelings.

Yet I was taught to take responsibility for my own decisions. When dear Jack Hixon, the scout who became a mentor and close friend, asked my parents whether I could go to the south coast, they told him that question was for me, not them. They knew it was my life and they knew that if I was going to achieve my dream, then I had to go. They trusted me and I hope that trust was repaid because it was the best thing I could have done.

From my digs, I would phone home every night or they would call me, always at one minute past 6pm, when the long-distance prices went down, just to chat about the day and what we’d been up to. My mam would send me down care packages, with socks and underpants or toothpaste and deodorant, knowing that my £27-a-week wage would only get me so far. When I got into the first team, they came to games when they could, on the train or by coach.

When I came back in 1996, signing for my hometown club in a world-record £15million ($19m) transfer from Blackburn Rovers, I described myself as “just a sheet metal worker’s son from Newcastle”, something that just rolled off my tongue. I immediately worried what Dad would think because he and my mam never wanted credit, hated publicity, hated the limelight and didn’t want journalists knocking on their door. When it came, I felt like it was my fault. Thankfully, my dad just laughed.

Alan Shearer is presented to the Newcastle fans in 1996 (Paul Barker/PA Images via Getty Images)

They both kept working, even when I insisted they didn’t need to, because it was who they were and what they loved — my dad out of the front door at 7am and back at 4.45pm, with his tea on the table at 5pm sharp. He wanted to go to the club with his pals on weekend afternoons and then with my mam in the evenings. She wanted to walk down Gosforth High Street with nobody interrupting her life. It was as normal as normal could be. And it was beautiful.

One of my fondest days came in my mid-20s when I bought them a house — they had stayed in Park Avenue until then — and I promise I’m not saying this to make myself look good. Even so, there is a selfishness to the memory because of how amazing it made me feel. They never asked for anything and they never wanted anything, but that was the moment I felt like I had achieved something with my life. More than playing, more than scoring, more than representing England.

The truth is this. When I’m asked who my hero is, I invariably say Kevin Keegan, whose debut as a Newcastle player was my first game as a fan; he scored, we won and that was that: dreamland. But it’s not strictly accurate. I’m trembling as I say this, but my mam and dad are my heroes, always have been and always will be. For everything they’ve been through, for everything they’ve done, for the people they are. They’re amazing. Amazing.

My dad’s hero, in football terms, was Jackie Milburn — “Wor Jackie” — the legendary centre-forward who lifted three FA Cups with Newcastle in the 1950s. Growing up, Newcastle was always part of our lives — in Park Avenue, how could it be anything else? — and Dad had seen the team win the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup in 1969, still our last piece of silverware, and he’d been to Wembley for a less celebratory FA Cup final in 1974 when Liverpool stuffed us 3-0.

In 2006, by which time my body was broken and I was on my last legs as a player, I overhauled Jackie’s total as Newcastle’s record goalscorer. After our victory over Portsmouth, I hobbled into the player’s lounge at St James’ and my dad broke the habit of a lifetime and said, “Well done, son, I’m proud of you.” He’d seen me win the title with Blackburn Rovers, he’d seen me captain my country, but he didn’t articulate those words until right near the end.

Don’t get me wrong, I wasn’t craving affirmation. I was never starved of affection. I don’t know if it’s a Geordie thing or a generational thing, but for my parents, showing love was about the day-to-day. It was about those telephone calls or visits home. When we met and chatted after games, we’d have a laugh about what happened, talk about the result and whether the referee was crap or good, but he didn’t shower me with praise, even on the day I scored five goals for Newcastle against Sheffield Wednesday in 1999.

I was fine with that. Perhaps part of him suspected that I was surrounded by people telling me I was great and perhaps he recognised that wasn’t wholly healthy. Perhaps it was just who he was. He never showed off, never boasted about his footballer son, never revelled in reflected glory. But I would look at him and I could feel the pride oozing out of him. I knew that he was the proudest man in the world. I knew. I always knew.

I was present at the Freeman Hospital in 2008 when Sir Bobby Robson opened the Cancer Trials Research Centre that bears his name. The centre was funded by donations to the Sir Bobby Robson Foundation, of which I’m a patron. Fabio Capello, then the England manager, was there along with plenty of other football dignitaries and, as always, we marvelled at Bobby’s determination to carry on and his zest for life.

Alan Shearer with Fabio Capello and Sir Bobby Robson at the launch of the cancer unit (Owen Humphreys/PA Images via Getty Images)

Earlier this year, I was back at the Freeman, back at the centre. My dad was having treatment there and we were walking up the corridor with photos of Sir Bobby on the walls around us. Photos of me. I felt light-headed at how surreal it was. Whoever we are, we all try to do our bit, don’t we? We all try to give back, we donate money or our time to good causes, but it’s never quite real until it’s you or your family and then it’s almost like an out-of-body experience.

My dad fought cancer when he was 65 and got over it. He passed the five-year mark and reached 70 without a reoccurrence and we all thought — we all hoped — it was back to normality and everything was fine. He was 80 this year and to see him over the last few months was horrible. I’ve never known anguish like it; if I could only have taken the pain away, taken everything away, then I would have done it in a heartbeat.

The good thing — if you can call it that — was that his suffering was brief. One Sunday in mid-February, he came home and told my mam he didn’t feel so well and could she get him a doctor’s appointment. They got him in the next day. By the Thursday afternoon, I was sitting in front of a specialist at the Freeman asking about the prognosis and being told, “Unfortunately, it’s a matter of weeks or months.” All I could think was, “Please, someone pinch me. Am I asleep here?”

The cancer was back and it had spread from his lungs and into his brain, so pretty soon we were at the Sir Bobby centre and he was receiving chemotherapy. He’d made the decision that he wanted to fight on the off-chance it might give him another year or two. By then, I think he knew that it was a losing battle and, do you know something, I think he fought that last fight for our benefit rather than his.

When I wrote earlier about the importance of what we’ve been through, this is what I meant. Not because it’s unusual or special, but because it’s the same for us as it is for so many people, for too many people. To paraphrase Sir Bobby, cancer takes no account of who you are, what you look like, what you’ve done or the colour of the stripes on your back. It is democratic and it is evil. My dad fought and I respect him so much for it. One day, together, that fight will be won.

Once Dad got the news that he wasn’t getting better, there was no shirking it. He didn’t shirk anything. He loved working, he loved a laugh at the club with his mates and he faced everything head-on. That included his own passing. He told us exactly what he wanted and he told us that when the time came, he wanted to be at home. And he was. We were all there with him and it was very peaceful. The pain had gone.

On the way, there were light and dark moments. We knew what was coming and one day when I was trying to switch off for a couple of hours, I got a call from my mam, “Dad wants you and Karen home now. He’s ready to go.” In the end, he lasted for another 27 or 28 hours, but on that final evening, he talked through his life, the people he had fights with and didn’t like and plans for his own funeral. He was laughing and reminiscing. The clarity was amazing.

A little later that night, he was dozing. It was a Champions League week, so I whispered something about popping downstairs to check the scores, just for a short break. Please bear in mind that this was an incredibly intense and upsetting time, but I struggled with the TV remote and I must have said something to my mam along the lines of, “How the hell does this thing work?” In the end, I gave up and went back up the stairs and forgot about it. The football didn’t matter.

At 6am, there was another emotional surge. My dad was suddenly adamant he didn’t want to die in bed. Gently, I tried to reason with him. “But you’re comfortable here,” I said. At the same time, I could understand his impulse. He wanted to be up and alert and around people. But it meant a lot of upheaval, moving out the settee from the living room, finding another bed, which was delivered around 11am, and then the trauma of getting him into a wheelchair and downstairs.

Honestly, it was awful, but with a lot of sweat and quite a few tears, we got him there. He was as weak as you could imagine, but we had fulfilled his final wish. And do you know what he did next? Do you know what he did? He picked up the remote control and said, “Right, son, this is how you use it.” What? Excuse me? “I heard you last night. You couldn’t work out how to watch the football. Here, I’ll show you.”

Oh my god, Dad! Unbelievable. Stubborn and determined until the end.

He died later that day.

For obvious reasons, this has been tougher on my mam than anyone else. She’s coping OK, she’s doing the best she can, but my dad’s loss is a gaping hole. All told, they were married for 59 years and one of the most poignant episodes of the past few months came a week or so before Dad passed away when he turned to her and said, “I don’t think we’re going to make 60 years, pet.” I don’t mind admitting, that set me off. I don’t mind admitting, it sets me off now.

Mam is an incredible woman. She worked hard and kept working, she got home and cooked for us and cleaned up and kept our little council house on Park Avenue tidy, like many mams did back then. She looked after Dad, she looked after all of us, the glue that kept the family together. She saved and put money away, she made sure Karen and I never wanted for anything, even when that meant letting go. So we rally around her. It’s all about Mam now.

Their story, my story, is probably not too different to yours. For good or bad, we’re all a product of our parents and we carry them with us wherever we go. But without my dad here, part of me feels lost and untethered and I hope you can understand. Without wishing to be too maudlin, perhaps you might think of him when the Match of the Day theme sounds this weekend. I know I will. And, if it’s right and feels appropriate, think of your family, too.

Without my dad throwing a ball at my pudgy little legs, I would never have been Newcastle’s No 9, wheeling away from the Gallowgate End with my right arm in the air. Without my parents filling and emptying their penny bottle, I would never have owned the boots to become a footballer. My life is his life, my mam’s life, their sacrifice, their normality, our stubbornness, my dream, those things we carry, always on time, never late and our silent, unspoken pride in each other.

(Top photos: Getty Images and Alan Shearer; design: Dan Goldfarb)

Read the full article here