Take the long way from Dallas to Houston and a series of small highways will guide you through towns with names like Italy, Friday and Lovelady. You’ll pass general stores and sun-baked fields dotted with broken wind pumps and tractors that look plucked straight out of an old Western film.

Swing the door open at the aptly named Bullet Bar in Gun Barrel City and plop yourself down on a barstool. Order a Shiner Bock or a Lone Star, the popular beers around here, and you’ll notice something peculiar: the television in the corner of the place is broadcasting soccer highlights from the European Championship and Copa America.

The latter of those two tournaments is being played right now just north of here in Dallas and a hundred or so miles south in Houston. We’ve come to Texas to do something a little ridiculous: attend four Copa America matches in four days. In that span, we’ll get a look at half of the entire field of teams as we ferry back and forth between Texas’ two largest cities. It’s a nearly-1,000-mile drive, more or less.

This is just the second time in the tournament’s history that Copa America has been contested outside of South America. Immigrant communities across the United States will turn out in force to support their respective home teams as they battle for continental dominance. The U.S., as hosts, are also playing in the tournament, as is Mexico, the country’s southern neighbor.

On the surface, the tournament seems a bit of an odd fit in a place like central Texas, with its deeply American aesthetic. This is the land of Friday Night Lights, where high school (American) football stadiums sometimes approach the size and cost of professional ones. Yet Texas has always had an important place in American soccer. Nacogdoches, the oldest city in the state, produced arguably the country’s greatest ever men’s player, former national team legend Clint Dempsey. Carla Overbeck, a legend of the women’s game, hails from the state. Go back further and the list gets even longer — Kyle Rote, Jr., maybe the United States’ first real phenom, was a Dallas native.

Clint Dempsey celebrates one of his 57 goals for USMNT (Hunter Martin/Getty Images)

Unquestionably, American football remains king in Texas and nearly everywhere else in the United States. But the scene between Gun Barrel City and Houston paints a decent picture of the inroads soccer is making here: pristine soccer pitches are tucked in among the American football stadiums. At a gas station about halfway between the two cities a couple of kids root through bins of candy wearing a pair of jerseys — one sports a Lionel Messi Inter Miami kit, while the other wears a U.S. national team kit bearing the name of American superstar Christian Pulisic, who will take the field in Dallas in a couple of days against Bolivia.

It’s long been the hope of supporters of the game in soccer in the United States; that the interest of the country’s youngest generation will finally thrust the sport into mainstream relevance. It remains to be seen whether these two kids at Buc-ee’s will grow up to support Major League soccer side FC Dallas or the NFL’s Dallas Cowboys.

Day 1: Chile v Peru, AT&T Stadium, Arlington

The first of the matches in the Lone Star State is an encounter between Chile and Peru. It’s Friday night, and we’re at AT&T Stadium in Arlington, outside of Dallas.

The facility is an embodiment of the old saying: “Everything is bigger in Texas.” It looks like a spaceship among a sea of parking lots and its most distinctive feature is likely its video screen. Suspended above the playing surface, the screen was for a time the biggest in the world. Even in the best seat in the house, your eyes are often drawn upwards to it. You might have paid thousands for your seat here, but you’ll likely end up watching the game on a giant television.

A new grass field has been installed for the Copa America

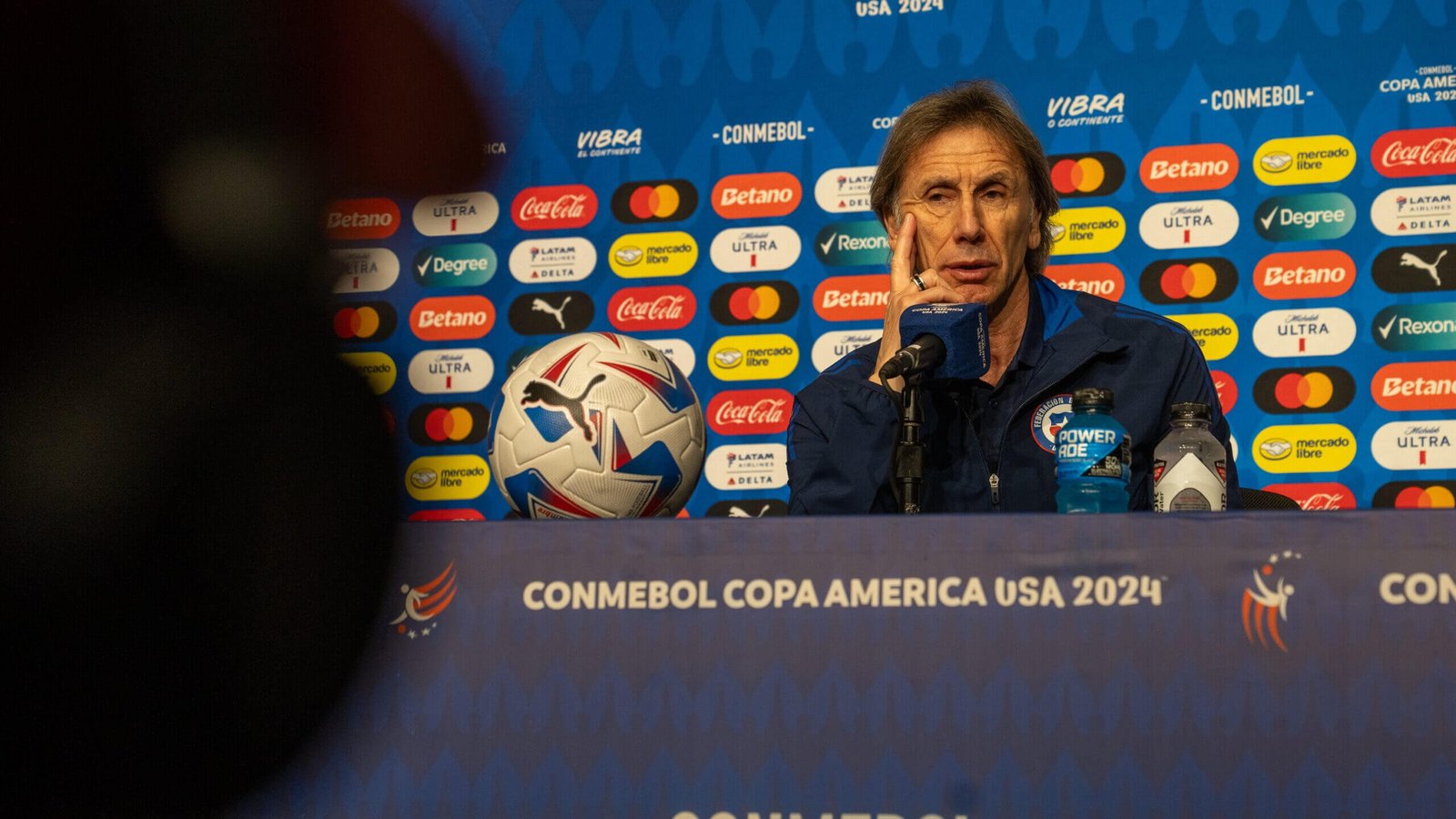

A few hours before kickoff, Chile head coach Ricardo Gareca steps off the team bus in the stadium’s lower level. Gareca is a legend in parts of South America, having had a lengthy and varied playing and coaching career that more or less qualifies him as a mercenary. He looks old school, the kind of wiry, long-haired Argentine that you could easily imagine chain smoking in the technical area.

Today’s match has some special overtones for Gareca, as he spent a full seven years coaching Peru, leading that country to some of their greatest-ever results, including a memorable run in the 2018 World Cup. He departed in 2022 after a disagreement with the Peruvian federation over the direction of the program. There were hurt feelings on both sides.

The loss of El Tigre, as he’s sometimes referred to, was a difficult pill to swallow for Peruvians, who still hold him in high regard. It’s a bit like losing a long-time girlfriend, one local Peru fan tells me in the leadup to the game, one who you love dearly.

“At some point, when the relationship has run its course,” he says, “you simply have to let go. And then you see her with another man — you might be happy for her, but you still hate your life a little bit.”

Peru fans have certainly been hating life as of late. They’re mired at the bottom of the table in CONMEBOL qualification for the 2026 World Cup with two points from six games and they’ve shown no signs of improvement. Chile haven’t been much better but there’s at least a buzz surrounding the appointment of Gareca, who joined in January.

The head coach is far from the only thing driving the Clásico del Pacífico. South American football is dominated by the rivalry between Brazil and Argentina and to a lesser extent the one between Argentina and Uruguay, two of the fiercest matchups in the world. This rivalry, though, has its own heat and is sometimes considered among the most hotly-contested on the continent. Chile and Peru are bordering nations and fought a years-long war in the 19th century. In the 1970s, the country’s respective dictators, Juan Velasco and Augusto Pinochet, seized upon the rivalry and imbued it with deeply nationalistic overtones, pouring gasoline on the fire.

Peru’s bottom-dwelling status isn’t doing anything today to dampen the spirits of their fans. The country’s supporters travel legendarily well, and today is no exception. The sprawling expanse of parking lots outside of AT&T stadium are awash with beer, music and the country’s iconic red-and-white kits. There are fans dressed as Incan emperors in the 100-degree heat, their gold shoulder pads and headdresses sweat-soaked. Others sport ponchos. Nobody looks particularly comfortable.

Brayan Arizmendi isn’t wearing a shirt at all. He made the 16-hour drive here from Charlotte, North Carolina, with his two children. Born in Santiago, he moved to the United States in 2019 and any opportunity to see la Blanquirroja in his adopted home is a precious one. Seeing them take on Chile is just an added bonus.

“I would have come much further than 1,000 miles to watch this game,” says Arizmendi. “In the Clasico Pacifico, you win by any means necessary.”

Brayan’s enthusiasm is present in many of Peru’s fans, and that attitude eventually makes its way into the stadium. The place is massive and cavernous and certainly lacking a bit of soul, something akin to a Walmart. Yet even in this huge venue the voices of the 35,000 or so Peru fans in attendance is thunderous.

The match itself is a back-and-forth, tense affair, but one that never produces a goal. About 35 minutes in, Peru’s Luis Advincula hobbles off after going down injured off the ball.

It seems possible the injury was caused by the pitch in Arlington, a natural grass field laid down in recent weeks to replace the turf that’s normally used for American football. Peru head coach Jorge Fossati agrees. In his post-match press conference, he’s critical of the playing surface. He’s the latest of the tournament’s participants to criticize the quality or dimensions of the pitches, a gripe that will become one of the central themes of the tournament’s opening week.

GO DEEPER

‘It’s not normal grass’: Why field conditions at Copa America are causing concern

Careca, after the match, feels confident in his side’s performance and doesn’t feel that their chances of advancing have been hurt. The task ahead of his team, though — and Chile’s, for that matter — feels massive for one reason alone: they must face Lionel Messi’s Argentina, the defending champions, and also a promising Canada side.

As we leave the parking lot after the match, a Texas State Trooper asks us what we came for — soccer or baseball. The Texas Rangers play in a stadium next door, and the crowd that’s filtering out of that stadium looks a lot different than the one we were just in.

Day 2: Mexico v Jamaica, NRG Field, Houston

The drive down to Houston was a breeze, even in the oppressive heat. We stopped a couple of times on the way, once for some BBQ and once for a couple of treats at Happy Donuts in Bois D’Arc, Texas. Population: 10 people.

Tonight, at NRG Field, America’s home team opens play in Group B.

The Mexican national team — El Tri for short — has managed to carve out a foothold in the United States that even the actual U.S. national team has struggled to do. The U.S. is home to nearly 40 million Mexican immigrants and a chunk of them, right now, are wandering the parking lots outside the stadium before their side take on Jamaica.

It’s a different vibe than the Chile/Peru scene the night before. This one feels more family-oriented, with first and second-generation Mexican immigrants manning grilles and coolers. The soundtrack is a cacophony of banda music with some cumbia and reggaeton mixed in.

It feels just a tad less festive than the scene we witnessed the night before. Much of that likely has to do with the moment Mexican soccer finds itself in as a whole. El Tri were pitiful at the 2022 World Cup and they’ve also lost the once-firm grasp they had on regional dominance, regularly losing to the United States in meaningful competition. LigaMX, the top flight of Mexican club soccer, is still thriving but MLS has made inroads there as well, capturing Messi and growing in leaps and bounds every year.

That energy is matched inside the stadium itself, where there are more than a few empty seats. Important matches played by the Mexican team in the United States regularly sell out NFL stadiums. Tonight, large patches of blue-and-red seats are visible among the sea of green. Tournament organizers didn’t do themselves any favors by selling even the cheapest seats at more than $100.

Manuel, who looks to be in his 20s, is wearing a lucha libre mask, the kind sported by professional wrestlers in Mexico. The opening around his mouth is just big enough to swig beer through. He doesn’t seem particularly thrilled to be here.

“I don’t expect much out of this team,” he says in Spanish. “I don’t know that anybody who is here expects much of this team. I was in Dallas in 2014, when we played Ecuador — the stadium was full (of 84,500 fans.) Look around now. For a Copa America match. I don’t know if people couldn’t afford to be here or if they just don’t care. Either way, I don’t blame them.”

There are a smattering of Jamaicans in the crowd and they’re just happy to be here.

Things start slowly for the Mexicans, and they go from bad to worse when their captain, West Ham midfielder Edson Alvarez, collapses to the turf in agony, grasping his left hamstring. He is Mexico’s heart and soul. Just a day earlier, Alvarez spoke eloquently about his obligation to lift up this downtrodden Mexico team. Now, he’s being helped off the pitch by his team-mates. Even the Jamaican players feel for Alvarez, with more than one of them offering a sympathetic gesture.

In Alvarez’s absence, Mexico rely on an entirely unexpected source for their match-winner: outside back Gerardo Arteaga hits a wonderful, driven shot midway through the 69th minute to save Mexico from a disastrous opening result.

Gerardo Arteaga 😮💨 pic.twitter.com/A9sxearXup

— CONMEBOL Copa América™️ ENG (@copaamerica_ENG) June 23, 2024

Alvarez’s injury — and the lukewarm performance in general — will do little to comfort Manuel, or any other Mexico fan in attendance.

Day 3: USMNT v Bolivia, AT&T Stadium, Arlington

We’re heading back to Arlington. The United States is opening play today against Bolivia, maybe the worst team in the tournament (certainly by FIFA ranking, No 84).

You can tell a lot about the evolution of soccer’s popularity in the United States by the scene at a USMNT game, particularly the jerseys you see at it. There are the Denim Kits, the iconic, acid-washed shirts from the ’94 World Cups, usually worn by the team’s oldest fans or by its hipsters. Then there are the “bomb pop” and “Waldo” kits, which feel more like millennial fare. Newcomers to the program sport the team’s latest fits, like the tie-dye get-up the USMNT is wearing this tournament.

Others have a different look, like seven-year-old Oliver Brazell. Shirtless, covered in body paint and sporting an American flag as a cape, Brazell fits right in with the other costumed fans in his section: a couple of fans dressed up as George Washington and one sporting a bald eagle mask.

The fact that there’s anybody at this game at all probably feels like a minor miracle to anyone who suffered through the dark ages of the sport in the U.S..

Today, a crowd of nearly 50,000 will file into AT&T Stadium to watch the United States.

They are almost entirely U.S. fans, another heartening data point. Just a couple of weeks ago, the USMNT played Colombia outside of Washington, D.C. and — as has so often been the case — the game felt like an away match.

Much of the chatter surrounding the USMNT at this tournament centers around the performance of Gregg Berhalter, the U.S. head coach. Some of the program’s most vocal fans — on the internet, at least — have been calling for Berhalter’s dismissal. Some point to the USMNT’s lack of a “signature win,” a victory over a major opponent in a major tournament. Others say the U.S. needs a more seasoned international head coach ahead of the 2026 World Cup, which will be hosted in the U.S., Canada and Mexico. Still others just like to complain.

The chatter, though, feels real. The 2026 World Cup looms large and crashing out in the group stage of this tournament could very likely cost Berhalter his job.

As a player, he was on the bench for one of the USMNT’s biggest-ever upsets: its shocking defeat of Argentina at the 1995 Copa America. Back then, the tournament meant little to most of the American public. Soccer as a whole didn’t mean much. Times have changed a bit.

“Everybody knows how important this tournament is to the people of South America,” USMNT goalkeeper Matt Turner says ahead of the match. “It’s one of the oldest tournaments in the world and it’s only every so often that the U.S. gets invited to take part in it. We have to cherish those times. It’s a chance for us to play outside of our region and go up against some of the top teams in the world and compete for a trophy. This is probably, outside of the World Cup, the biggest tournament we take part in.”

From the opening whistle, it becomes clear that Bolivia is not one of the teams that Turner is referring to. They are awful in nearly every phase of play and they go nearly the entire match without a single touch in the U.S. penalty area. The USMNT can sometimes play down to its opponents but that doesn’t feel like the case today. Pulisic gets the first goal minutes into the first half and just before half-time the Monaco striker Folarin Balogun doubles the lead.

The American Outlaws, the primary supporters’ group of the USMNT, are sitting in the north stands and they feel heavily invested in the match. It has to be said, though, that they’re a minority here. The bulk of the crowd is made up of casual fans, families who look like they came straight from a youth soccer game and couldn’t care less about Berhalter or any of the other points of discussion these days. Financially, that’s probably a heartening development for U.S. Soccer as it continues to try and cross the divide into mainstream relevance.

GO DEEPER

USMNT 2-0 Bolivia takeaways: Christian Pulisic sets the tone with set piece precision

“I don’t pay too much attention to (the minor details),” says Kevin Tremaine, a 28-year-old who made the drive up from Houston with his wife and son. “We go to games when we can — this one is obsessed with Pulisic.”

Tremaine motions to his kid, who looks to be five or six years old. He’s sporting a Pulisic shirt as he stands on his seat to see the action unfold. He lets out a groan as USMNT go forward and hometown hero Ricardo Pepi, an FC Dallas academy product, misses a point-blank chance. He’ll do that again before the end of the match, maybe sparing Bolivia from a truly ugly loss.

It’s a heartening start for the U.S. and for Berhalter, too.

Day 4: Colombia v Paraguay, NRG Arena, Houston

Our trip draws to a close on day four back in Houston. A flat tire hamstrung us on the drive south and we pull into the lot at NRG Arena just minutes before kickoff, walking in with a group of Colombia fans.

Instead of heading to the press box, we join a pair of supporters in the lower bowl just as the anthem gets underway. It is an absolutely electric scene — every one of the 67,059 fans in attendance, it seems, belts it out in full voice.

Colombia’s history in the United States is unquestionably attached to the 1994 World Cup, where Los Cafeteros — who some picked as dark horse favorites to win the tournament — were shockingly defeated by the U.S., who were aided by an own goal by Colombia defender Andres Escobar. He was murdered weeks later, upon returning home to Colombia.

Nearly every fan in attendance here is sporting Colombia’s signature yellow, blue and red colors and many of the jerseys bear the names of current and former players: Rodriguez. Valderrama. Falcao. There are also no shortage of Escobar jerseys. The player’s legacy is celebrated by Colombia’s fans, who still hold him in the highest regard. To our right, a father and daughter have come to the match wearing matching Escobar shirts.

“Andrés siempre está con la afición,” says Esteban Moreno, who traveled from New Jersey for the match. “Andrés,” he says, “is always here with Colombia’s fans.”

The crowd here, on a Monday afternoon in 100+ degree heat, dwarfs the 53,673 that turned up for Mexico’s encounter with Jamaica on Friday evening. The energy is bouncing and from the opening whistle, the crowd is engaged, following their team’s every move on the pitch. There are no Paraguay fans in sight.

Mixed in with the Colombia faithful is a man who refers to himself simply as “T.K.” He and a friend have turned up for the match wearing a pair of Arsenal kits and they’re clearly unattached. They stop for a moment before hurrying to their seats.

“We don’t get a chance to see much high-quality soccer here,” says T.K., “So we were always going to come.” When asked whether he’s ever been to a Houston Dynamo match — the local MLS side — T.K. and his friend simply laugh and walk away. American club soccer remains a tough sell here.

As in 1994, Colombia has entered this tournament in fantastic form. They’re unbeaten in 23 matches and in the buildup to the tournament they fed two Copa America participants — Bolivia and the United States — into the shredder. They grab a hold of this match almost immediately and within 20 minutes their faithful are chanting “!Olé!” with every pass. Ten minutes later, Colombia nab the opening goal.

The place turns into a madhouse, beers thrown aloft, vuvuzelas and horns blaring. In the supporters’ end, someone has smuggled in a smoke bomb, which gets popped. Eventually, it sets the fire alarm off in the press box. Paraguay are simply never in the match. They manage to score a goal against the run of play early in the second half but Los Cafeteros wrest back control of the match and maintain it until the final whistle.

(Logan Riely/Getty Images)

The scene on the walk back to the car, around 8 p.m., is a giant party. Children knock soccer balls across the pavement and adults knock back beers and drag off joints and weed pens. One Colombia fan, sporting a tri-colored mohawk, walks backwards and screams “Vamos, Tricolor!” and is promptly swept off his feet when he falls over a beer cooler. He groans in pain while his friends point and laugh.

It’s been a long four days, but it’s been a blast. We wander over to a group of Colombia fans, ask them for a beer of our own and crack it open while we wander back to the hotel.

(Photos: Pablo Maurer/Design: Dan Goldfarb)

Read the full article here