It’s no exaggeration to suggest that Xabi Alonso’s first full season in management should be considered one of the most impressive campaigns in the history of the European club game.

To end Bayern Munich’s 11-year winning run is remarkable in itself. But Alonso took charge of Bayer Leverkusen a couple of months into the 2022-23 season, when they were second-bottom after just eight matches. To oversee such a dramatic turnaround was almost unthinkable in itself — but Alonso’s side have also gone the league season undefeated. On Wednesday, they will contest the Europa League final against Atalanta, and then they are heavy favourites to complete a domestic double in Saturday’s DFB-Pokal final against second-tier strugglers Kaiserslautern.

It comes as no surprise that Alonso is an excellent manager. Of all the top-class players from his era, few were considered such cerebral geniuses on the pitch. Playing football is about combining athleticism and intelligence, and the players who lack physical qualities yet thrive because of their reading of the game tend to be suited to coaching. Pep Guardiola, Mikel Arteta and Didier Deschamps can be considered in a similar light.

“In Xabi Alonso, we have signed a coach who, as a player, was an absolute world-class professional for many years, an intelligent strategist and very successful in three of the most demanding European leagues,” Leverkusen’s sporting director, Simon Rolfes, said upon his appointment. How many others are referred to as a “brilliant strategist” for their work as a player, rather than as a manager?

(Ralf Ibing/Getty Images)

Alonso was coached by Rafael Benitez, Jose Mourinho, Carlo Ancelotti and Guardiola, among others. Few had a better footballing education but Alonso has gone his own way. Given his playing style, it should also come as no surprise that Alonso’s management style is based around passing. The precise type of passing, however, isn’t quite what we might have expected.

As a player, Alonso was defined by his long-range distribution — perhaps more so than any other midfielder of his era.

Take his first season at Real Madrid, 2009-10. Of the players who played more than 50 per cent of their side’s minutes that season, Alonso was the outfielder who attempted the highest number of accurate long passes per game, as defined by Opta — judging from the stats alone, you would think he was a goalkeeper.

These were usually pinpoint diagonal balls out to the wingers. This was basically Alonso’s identity, particularly when compared to his international team-mates, accustomed to Barcelona’s shorter form of passing. Sergio Busquets, Xavi and Andres Iniesta kept it simple. Alonso offered variety and more range. At Euro 2012, for example, look how many more long passes — the green and yellow bars below — he played compared to his team-mates.

This was noticeably different from the dominant Spanish — and Barcelona — style. Xavi, in particular, was so focused on short passing and preserving structure that he often turned down the opportunity to launch a counter-attack or hit a long diagonal.

Alonso’s style evolved in his later days. Under Guardiola at Bayern Munich, he played deeper, which theoretically meant he could play longer passes, but his passing style changed. Alonso became better at punching balls through the lines to team-mates in central positions. He could still play the diagonals but they were no longer the defining feature of his game.

Perhaps, over time, Alonso played so many diagonal balls that he eventually realised they weren’t overwhelmingly effective. Pinpoint crossfield passes got supporters applauding, but how beneficial were they to the team?

This was a subject covered at length in a presentation a decade ago at the Opta Pro Forum, a gathering of football analytics obsessives. The presenter, Colm McMullan, is notable for inventing the Stats Zone app, which, in 2010, was revolutionary as the first way to access real-time in-depth match data from your phone. Using his understanding of Opta’s data, McMullan put together an argument against long crossfield passes.

It wasn’t simply about the low accuracy rate of those passes — although that formed part of his case — but also about what happened next. Those passes, even when finding a team-mate, rarely resulted in a positive outcome. In part, this was because those passes were often finding a player who was holding width, but who was isolated and unable to combine with his team-mates.

McMullan’s discussion was picked up by the influential German tactics website Spielverlagerung, where writer Tom Payne — now an analyst at Bolton Wanderers — suggested there was one player to whom the theory might not apply.

“Xabi Alonso can be considered an exception to the rule,” he wrote. “Unlike his former Liverpool team-mate Steven Gerrard, Alonso’s diagonal switches of play are often made with great pace and low to the ground, which negates issues with (other players’ diagonal) passes.”

Managers increasingly seemed to understand this. Take the Arsenal side coached by Arteta, Alonso’s childhood friend — and, one suspects, his future managerial rival at some point. In a recent interview with The Athletic, Arsenal midfielder Declan Rice explained how diagonal passes, a key feature of his game at West Ham, had largely been discouraged by Arteta.

“The manager doesn’t like diagonals,” Rice explained while looking through some of his highlights from this season. “He likes diagonals if you’re going to gain an advantage from it but you see that one I’ve just played to Bukayo Saka, people will go, ‘That’s a great ball’, but let me rewind the clip and pause it… look, Saka doesn’t have anyone to play inside to, and he’s got another Brighton player coming over.”

Alonso has the same mindset. In a training session, he was filmed discouraging his players from playing long passes, and they’ve obviously got the message. Despite always using two players who hold width, and having a deep midfielder in Granit Xhaka who can switch the play, Leverkusen play very few long passes. Note their position in the bottom-right of the graph below. They’ve played the third-most passes in the major European leagues this season, but the fifth-fewest long passes.

And when calculated as a percentage, only Tottenham play a lower proportion of their passes long than Leverkusen.

Leverkusen still rely heavily on their wing-backs (usually Alejandro Grimaldo and Jeremie Frimpong) for attacking width and attacking incision but crucially, they are almost never found by long diagonal balls. Alonso wants to involve them after shorter passes — and this works excellently.

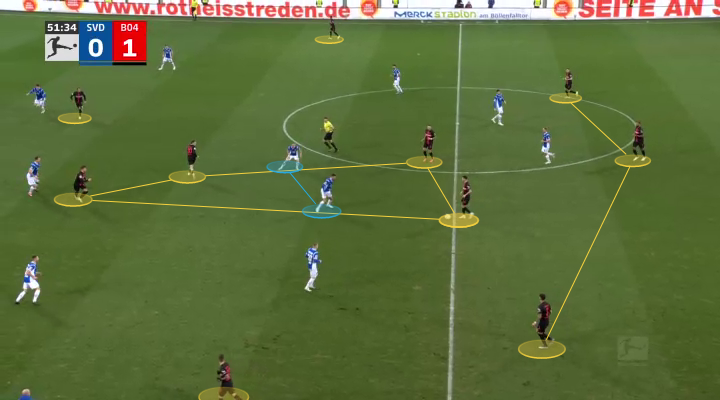

Here’s a good example, from Leverkusen’s victory over Darmstadt this season. It shows Leverkusen’s usual system — a back three, a midfield rectangle overloading the opposition’s holding players, then two wing-backs and a centre-forward.

Xhaka is on the ball. The key player in this move is Nathan Tella, the right wing-back. You might expect, therefore, the next pass to be Xhaka playing a big diagonal out to Tella. Xhaka certainly has this in his locker.

But no, that’s not how Leverkusen play. A big diagonal would force Tella to take a couple of touches to control the ball. He would have no support. And the opposition left-back would have the relatively easy task of running across to shut him down.

So here’s what Leverkusen do instead. Xhaka bisects two opposition midfielders with a difficult pass that finds playmaker Florian Wirtz between the lines.

Wirtz then dribbles the ball towards the opposition left-back, forcing him to engage. That allows Tella some freedom, and Wirtz slips the ball to him, running inside from the right.

Tella can hit the ball first time — and he does it brilliantly, slamming into the top corner.

That’s the key — Leverkusen want to use their wing-backs, but they want to use them in a position where they have support, and preferably where they can play the ball into the box first time.

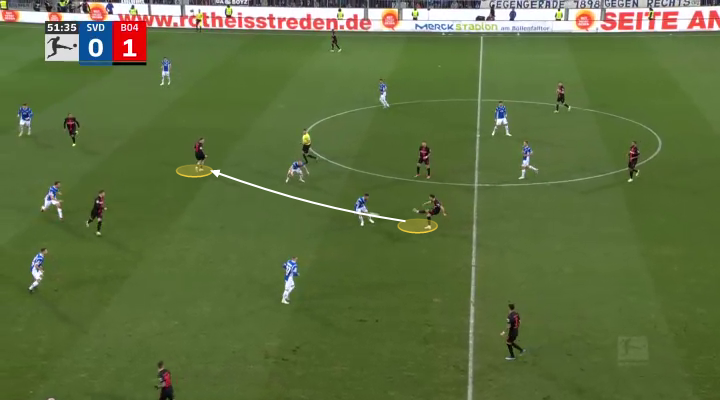

Here’s another example, against Cologne. Xhaka spots the run of Grimaldo — who, by reaching double figures in goals and assists in the league, is having one of the all-time best seasons for a wing-back. Xhaka thinks about playing this pass to Grimaldo but stops himself.

Instead, Xhaka again plays forward to Wirtz, who in turn plays up to centre-forward Victor Boniface.

It is then Boniface’s job to release Grimaldo on the overlap. The opposition right-back has been dragged inside, leaving space for Grimaldo.

His low ball into the box prompts a selfless backheel from Wirtz, and a calm finish from Jonas Hoffman.

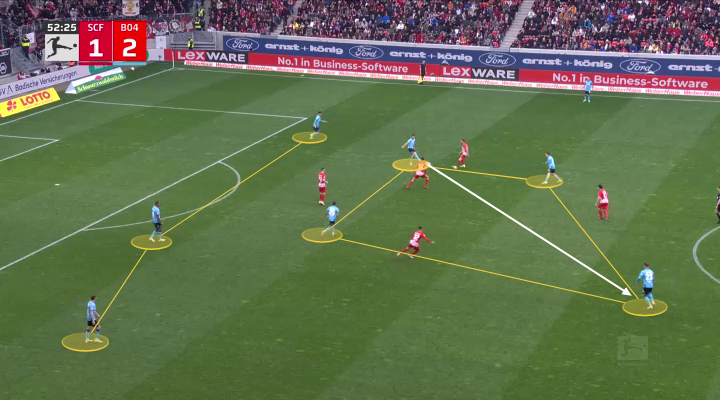

Here’s another example. The camera angle doesn’t show whether Xhaka could have played a long diagonal out to the near side, but he turns down the option of a simple pass to Grimaldo on the far side, and instead finds Adam Hlozek between the lines at the top of Leverkusen’s midfield square.

Hlozek turns and finds Frimpong, Leverkusen’s right-wing-back.

Once again, a Leverkusen wing-back can play the ball first time (rather than having to halt the momentum of the attack by controlling the pass, as he would from a diagonal ball, which would allow the opposition defence to organise themselves). He immediately crosses for Patrik Schick, who applies a lovely finish.

The one type of ‘switch’ Leverkusen play excellently comes in the opposition box, where they have scored an incredible number of goals this season from Grimaldo driving the ball to be converted at the far post, usually by Tella or Frimpong, such as this goal against Cologne.

That’s essentially their equivalent of the type of goal Manchester City have scored so often under Guardiola, perhaps most memorably with flying wingers Raheem Sterling and Leroy Sane combining. Leverkusen’s version features wing-backs, rather than wingers.

So what would Alonso the manager do with Alonso the player? Well, we might find out next season. The closest thing in European football to Alonso as a footballer is Girona’s Aleix Garcia, who has enjoyed a brilliant campaign with Girona. He has, unsurprisingly to anyone who has seen him play, hit more switches of play this season than anyone else in Europe’s ‘big five’ leagues.

And while he’s clearly enjoyed a brilliant season, there are drawbacks. Here’s one of his typical diagonal balls against Valencia at the weekend. Before Garcia has even played the pass, the opposition right-back knows to start running out towards the recipient.

OK, you can argue that the left-winger, Savio, might have a chance to dribble at the exposed right-back.

But by the time he controls the ball, the right-back is close to him, he has no support from a team-mate, and another opponent is about to double up against him.

This isn’t what Alonso wants from his players — but Garcia has been linked with Leverkusen for next season. Does Alonso want to add Europe’s best diagonal passer to give his side another option? Or would he reshape Garcia as he has Xhaka, and encourage him to be neater and more penetrative with his passing?

Those are questions for next season. First, Leverkusen have two finals in four days, to complete a treble and an undefeated season. It’s surprising enough that a Xabi Alonso side are already this good, but it’s even more surprising why they’re this good.

(Top photo: Rene Nijhuis/MB Media/Getty Images)

Read the full article here