There is a seminal 1986 journal article from the University of British Columbia, Canada. Ian Franks and Gary Miller tested novice coaches on their recall ability of critical moments from one half of an international match. On average, only 42 per cent were correctly remembered. Follow-up studies vindicated those findings.

In light of that, consider how much must be forgotten or (worse) misremembered across a major tournament, with so many games and so much emotion involved. Yet such tournaments can act as a tactical time capsule.

Let’s open up Euro 2024…

Fast starts and weird game states

Everyone knows major tournament games have cagey starts. Except, at Euro 2024, they were anything but. Four of the six fastest goals in European Championship history were at this tournament, including the two quickest: Nedim Bajrami for Albania against Italy (23 seconds) and Merih Demiral for Turkey versus Austria (57 seconds).

Six fastest goals at the Euros

| Player | Tournament | Team | Opponent | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nedim Bajrami |

Euro 2024 |

Albania |

Italy |

0:23 |

|

Merih Demiral |

Euro 2024 |

Turkey |

Austria |

0:57 |

|

Dmitri Kirichenko |

Euro 2004 |

Russia |

Greece |

1:05 |

|

Youri Tielemans |

Euro 2024 |

Belgium |

Romania |

1:13 |

|

Emil Forsberg |

Euro 2020 |

Sweden |

Poland |

1:22 |

|

Khvicha Kvaratskhelia |

Euro 2024 |

Georgia |

Portugal |

1:32 |

Those four goals were completely different: Italy making an error at their own throw-in against Albania, Turkey scoring from a corner, Youri Tielemans’ goal against Romania came from an incisive passing move in settled possession, and Georgia’s opener versus Portugal was a counter-attack.

It underlined the tactical variety of the tournament. There were teams built on nuanced tactical plans (Austria, Germany), who had build-up and pressing schemes similar to club sides, with head coaches recently in the club game. At the other end, some of the bigger and more recently successful sides, with coaches who have been in the international sphere for longer, were more structured and built around individuals (France, Portugal, England).

The average first goal time was 30 minutes, three minutes earlier than Euro 2020. It continues the trend of earlier goals, with the average opening goal at Euro 2016 on 41 minutes. There were more goals in the opening 30 minutes at this Euros than any other, which created weird game states because teams had longer to see out wins or chase a game. Barring some cagey third-round group-stage fixtures, it made for a more open tournament.

Old-fashioned strikers and goalkeepers

Big, goalscoring No 9s and shot-stopping goalkeepers are back in vogue. The standout strikers were Wout Weghorst (Netherlands) and Niclas Fullkrug (Germany), repeatedly used as second-half substitutes for a ball-to-feet striker. “His role is big because he scores goals,” said Germany head coach Julian Nagelsmann on Fullkrug. “It’s not always just about who starts. It’s also about the alternatives”.

10 – Wout Weghorst is the eighth player to make ten consecutive appearances for @OnsOranje as a substitute and the first since Luuk de Jong in 2016-2019 (13). Specialists. #EURO2024 pic.twitter.com/SdFTpNVqyY

— OptaJohan (@OptaJohan) July 10, 2024

Open-play crosses rose 12.6 per cent compared to Euro 2020, while the amount of chances created per game from crosses (6.7) was higher than either of the last two World Cups. Collectively, international coaches are not sharing the dogmatism of many club-level coaches and are prepared to be tactically flexible and change their attacking style rather than doubling down.

The return to traditional No 9s at the top end was matched by outstanding goalkeeping performances. Collectively, goalkeepers made saves which prevented 34 goals above average, over twice as good as goalkeepers at Euro 2020 (14 goals prevented).

Spain (Unai Simon), Slovenia (Jan Oblak) and Italy (Gianluigi Donnarumma) were three of the four countries with the best goalkeeper shot-stopping performances, but the goalkeeper of the tournament was Georgia’s Giorgi Mamardashvili.

He conceded more goals than anyone else at the tournament (eight) but saved 30 of 38 shots faced, including 11 out of 12 against the Czech Republic in the group stages — the most by a goalkeeper in a single Euros game at the past five tournaments. Tournaments are about having quality in both boxes.

Comebacks and late goals

Another tournament stereotype is that the team who scores first wins. That was true 71.4 per cent of the time at the last Euros. It happened three-quarters of the time at the 2022 World Cup. Not at Euro 2024 though.

The team who scored first won 55 per cent, with 11 draws and nine comeback wins. Part of this is explained by inferior sides scoring early against better opposition (see Georgia against Spain in the round of 16 — they eventually lost 4-1). It is the second Euros running in which teams have been permitted 26-man squads and five substitutes, which suited making personnel or tactical changes late in games, facilitating comebacks.

Finalists England and Spain won their semi-finals in regulation time despite conceding first, both inside the opening 10 minutes. Those nations won twice at the tournament from losing positions, as did the Netherlands. Euro 2020 winners Italy conceded first in all four games but still qualified in second from the groups. England became the first team to reach the final despite trailing in the quarter- and semi-final.

“The lesser teams, if you will… the smaller nations, have made progress,” said Slovakia head coach Francesco Calzona during the tournament. “We can cause problems for the more prestigious nations, but there is still a big gap.”

That was proved in England’s round-of-16 win over Slovakia. Gareth Southgate accepted England “had a problem we couldn’t solve” in trying to build through Slovakia’s mid-block and won through two set-piece goals.

Out-of-possession focus on counter-attacks, not pressing

Continuing from World Cup 2022 and the past two Premier League seasons, mid-blocks and counter-attacks are back.

There was a nine per cent drop in final-third regains this tournament versus Euro 2020, while direct attacks have risen 11 per cent. Opta defines those as sequences starting in a team’s own half, with at least 50 per cent forward movement, ending in a shot or touch in the opposition box. It may be linked to the increase in crosses, with riskier attacking approaches leading to more turnovers.

The main headline here is not the increase, but who is counter-attacking.

Spain had 28 direct attacks in 21 games across five tournaments between World Cup 2014 and World Cup 2022 — 1.3 per game. This Euros, they had 27 in seven matches, mixing their trademark high press with a compact 4-4-2 mid-block. When they made regains, passes went to No 9 Alvaro Morata early, midfielders ran beyond the ball and the wingers were ball-carrying outlets. Head coach Luis de la Fuente succeeded in making the team more “vertical”.

In fact, Spain’s first goal of the tournament, against Croatia, was a silky counter-attack — three passes in nine seconds from a regain in their own half.

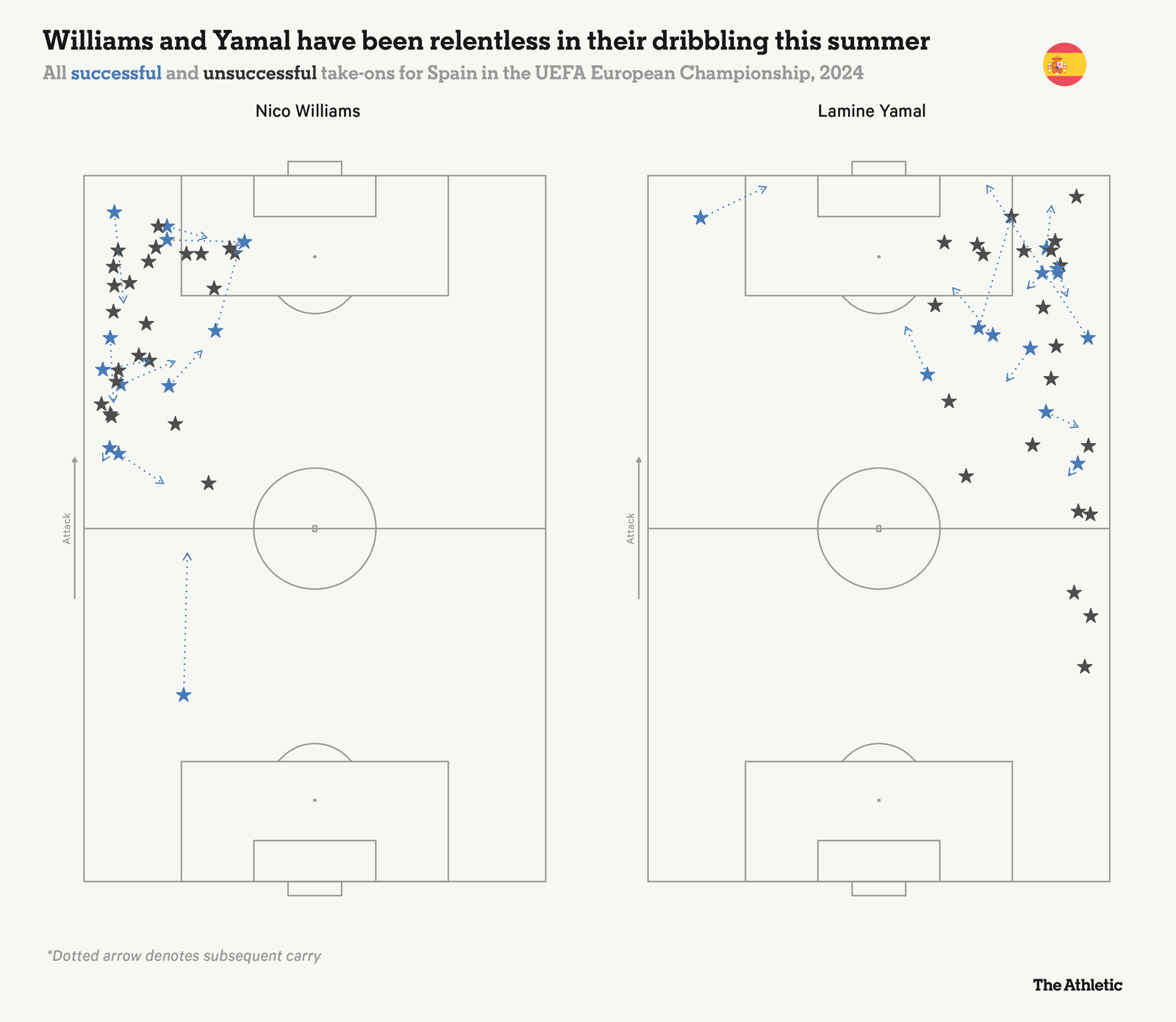

Fabian Ruiz was the architect, with a through ball for Morata, and he provided a similar assist for Spain’s fourth against Georgia. That time, Ruiz hit a long ball to release Nico Williams. The winger finished high past Mamardashvili after a successful dribble.

The Netherlands (20) had their most direct attacks at a major tournament since World Cup 2014, over three times as many as World Cup 2022 (six, in five games). Xavi Simons’ goal in the semi-final against England was one example, dribbling forward after a midfield regain and finishing from outside the box.

Likewise, Donyell Malen’s goal to seal the 3-0 round of 16 win against Romania or Cody Gakpo’s finish versus Austria. Both times, the Netherlands attacked immediately after a regain in their own half and released a forward down the left, who dribbled to the box and scored.

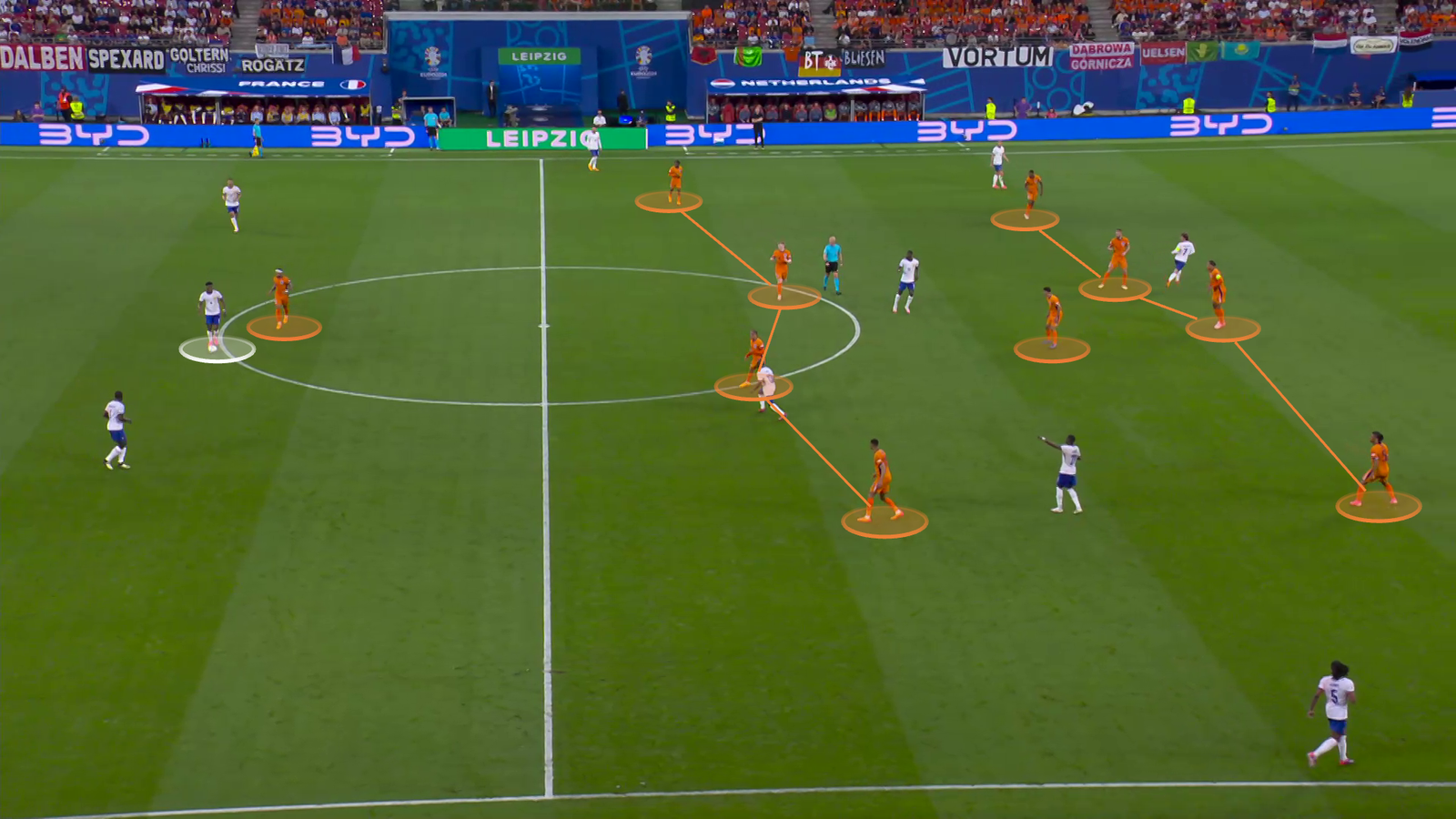

Simons, along with No 9 Memphis Depay, Gakpo and Malen, are versatile forwards who thrive with space, the chance to combine, and a disorganised defence to dribble at. Ronald Koeman’s team had 37 per cent possession against France in the group stages and 42 per cent versus England. Not total football, but a style which suited the personnel.

Koeman said in the group stages that “beautiful football doesn’t always work”, referencing the stylish passing of Dutch sides from yesteryear. Counter-attacks used to be the game plan for opponents against the Netherlands. Times change — the game changes.

You can win things with kids

Despite what Alan Hansen said on Match of the Day in 1995, England and Spain proved teams can succeed while — and because of — promoting youth.

“We’re never slow to put a young player into the seniors,” said Southgate pre-tournament. He and De La Fuente have similar backgrounds, coaching age-group national team sides. For them, trusting youth comes naturally.

Southgate’s midfield was particularly young in the knockout stages. Declan Rice, at 25, was the oldest of the midfield box, playing alongside No 6s Kobbie Mainoo (19), with Phil Foden (24) and Jude Bellingham (21) as No 10s. Spain’s Lamine Yamal has grabbed all the headlines as the youngest player ever at a Euros (he turned 17 the day before the final), though Williams on the opposite side is only 22.

2 – This is the first ever UEFA EURO or FIFA World Cup final to see two different teenagers start the match (Lamine Yamal and Kobbie Mainoo). Starboys. pic.twitter.com/UvbjS65JVD

— OptaJoe (@OptaJoe) July 14, 2024

Similarly, Julian Nagelsmann, who has his coaching roots in Hoffenheim’s academy, built Germany’s 4-2-3-1 around Jamal Musiala and Florian Wirtz (both aged 21) as narrow No 10s. Bart Verbruggen, for the Netherlands, became the youngest goalkeeper at a Euros in 60 years. Denmark and Slovenia, in Rasmus Hojlund and Benjamin Sesko, played first-choice No 9s who were under the age of 22.

These are examples proving a rule, not exceptions. Under-21s played 7,794 minutes at Euro 2024 and registered a combined 25 goal involvements (12 goals, 13 assists). It was over 2,000 more minutes than Euro 2020 (5,756), a tournament where the under-21s recorded eight goals and two assists. The proportion of goals involving an under-21 jumped from 7.6 per cent three years ago to 23 per cent.

It was fitting that the first two goals of the final, Williams’ strike assisted by Yamal, and Cole Palmer’s equaliser, set up by Bellingham, were combinations by players aged 22 or younger.

(Top photo: Nico Williams scoring for Spain in the final; by Justin Setterfield via Getty Images)

Read the full article here