If you’re the rare sort of person who can still form a semi-coherent thought during the second half of a Champions League knockout match, maybe you’ve noticed an odd pattern in Real Madrid’s run to this season’s final.

In the first leg of the quarter-final, Josko Gvardiol put Manchester City up 3-2. Toni Kroos was promptly taken off. Seven minutes later, Madrid tied the game.

In the second leg, Kevin De Bruyne scored amid a late flurry of City dominance to make it 4-4 on aggregate, Kroos is again substituted, and Real Madrid fought back to win on penalties.

First leg of the semi-final: Bayern Munich go up 2-1, Kroos takes a seat; seven minutes later, Madrid score.

Second leg: Bayern take a 1-0 lead, Kroos is replaced, Madrid score twice to go through to the final.

Over four games, whatever, big deal. Kroos tends to get subbed out in second halves because he’s still starting for one of the best teams in the world at 34. Madrid tend to score late in big Champions League matches because that’s just what they do. These things aren’t necessarily related.

For anyone who has watched Kroos dominate the game, it probably seems obvious that he makes his team better even now, in the twilight of his career. He’s a one-man sea of calm in the midfield storm, slinging perfect passes in all directions as if German doesn’t even have a word for pressure. His trophy case is bigger than your house; his teams have won a World Cup, seven league titles in two countries and four Champions Leagues — quite possibly soon to be five.

When Kroos announced this week that he’ll retire in the summer, his Madrid manager, Carlo Ancelotti, hailed him as “one of the best midfielders in the history of the game”.

Kroos’s final game for Real Madrid is set to be next month’s Champions League final (Daniel Kopatsch/Getty Images)

Here’s the weird part, though: Real Madrid have always done better when Kroos isn’t on the pitch.

Seriously, you can look this up in FBref’s playing time tables. In his 10 years in La Liga, the columns labelled “on-off” show that his team have had a better goal difference with him than without him only once, just barely, last season — and that was actually his worst campaign in terms of expected goal difference, according to which Real Madrid have been better without Kroos in every year on record.

Is it possible that one of the most admired midfielders of his generation has been secretly holding his team back all along?

If Kroos played hockey or basketball, these numbers might ring a few alarm bells. In sports where teams make a lot of subs and play a lot of games, you can get a decent idea of how good players are based on how their teams perform with and without them. When an NBA superstar like Luka Doncic puts up middling on-off numbers, it’s a genuine analytics puzzle.

Football is different. There are good reasons that “plus-minus” (a team’s goal difference or expected goal difference while a player is on the pitch) and “on-off” (the difference in a team’s plus-minus with and without a player) aren’t terms you hear a lot down at the pub.

“In basketball, you can calculate plus-minus for a season, for example, and it would kind of make sense,” says Lars Magnus Hvattum, a Norwegian professor who has published research on player ratings (he also runs a YouTube channel). “That doesn’t work for football.”

For one thing, there are twice as many players in football than in basketball or hockey, making it that much harder to tease out Kroos’s impact from, say, Jude Bellingham’s.

Football also has far fewer substitutions than those sports, where players rotate continuously in and out of the game. That means there are fewer opportunities to compare similar situations with and without Kroos on the pitch. Substitutions may follow goals or red cards that change the game, meaning that even when Kroos comes on or off, the rest of that match might look very different than the part he played in.

Kroos, left, has won 21 trophies with Real Madrid – so far (Oscar Del Pozo/AFP via Getty Images)

Then, there’s the problem of team-mates. If Kroos plays most of his minutes with the same players, it becomes hard to separate their contributions from his. As for how well the team plays with him on the bench, that will depend heavily on whether he’s replaced by Luka Modric or some anonymous B-team backup.

Add all this to standard concerns about the strength of the opponent, home advantage, fatigue and all the other factors that make it hard to compare minutes across matches, and you get a recipe for plus-minus and on-off stats that can very easily mislead.

“I don’t have Toni Kroos’s unadjusted numbers in front of me,” Hvattum says, “but in general, that’s just noise.”

The key word here, however, is “unadjusted.” Over the last couple of decades, researchers in basketball and hockey have come up with ways to correct for plus-minus’s blind spots — the quality of team-mates and opponents, home advantage, man advantages and so on — and produce player impact metrics that teams use in recruitment.

A decade ago, the pioneering football analytics blogger Howard Hamilton summed up the trouble with importing these techniques in a post titled “Adjusted Plus/Minus in football — why it’s hard, and why it’s probably useless.” Given the challenges of isolating players’ contributions in a low-scoring, low-subbing sport, he concluded that adjusted plus-minus “could become a valuable metric over time, but it will require a lot of care in its formulation, implementation, and interpretation”.

In recent years, though, adjusted plus-minus has started to make inroads in football. Academics, data companies and club analytics staff are all busy experimenting with ways to adapt established methods from other sports to one with more players and a lot less useful data.

These top-down player impact metrics are totally different from the more granular football stats we’re used to seeing but they have the potential to capture more of a player’s contribution than just what happens on the ball.

If nothing else, adjusted plus-minus models promise to be more useful than Kroos’s puzzling on-off figures, which Hvattum says he “wouldn’t look at at all”.

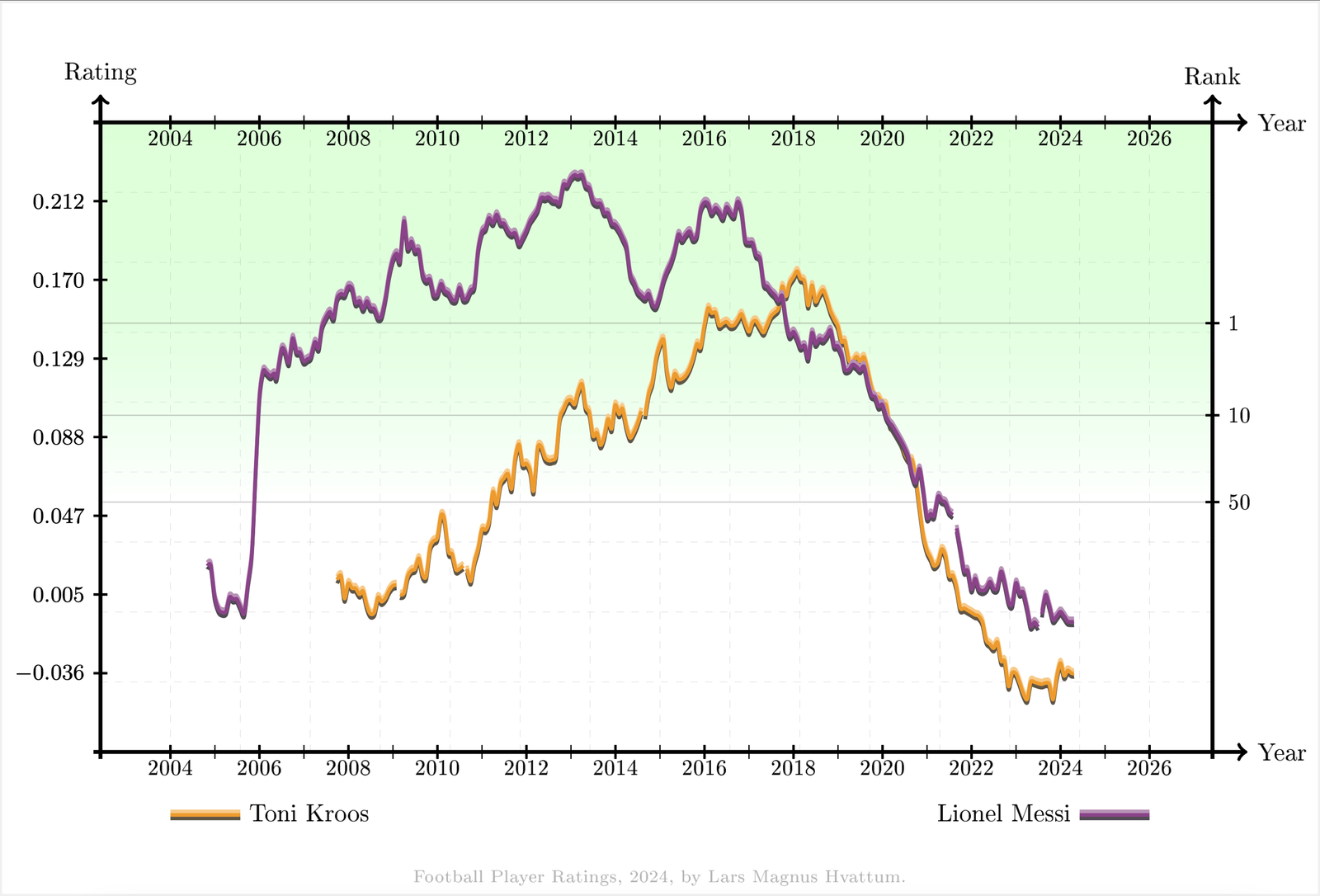

In Hvattum’s ratings, Kroos has always come out looking a lot better than his unadjusted plus-minus numbers suggest.

“In 2018, for a brief moment in time, my model had him ranked above Messi,” he says. These days, the model considers Kroos to be Real Madrid’s 15th-best player, which might support the idea that they’re generally better off when he’s on the bench, but even that is still good enough to make him a top-500 player in the world.

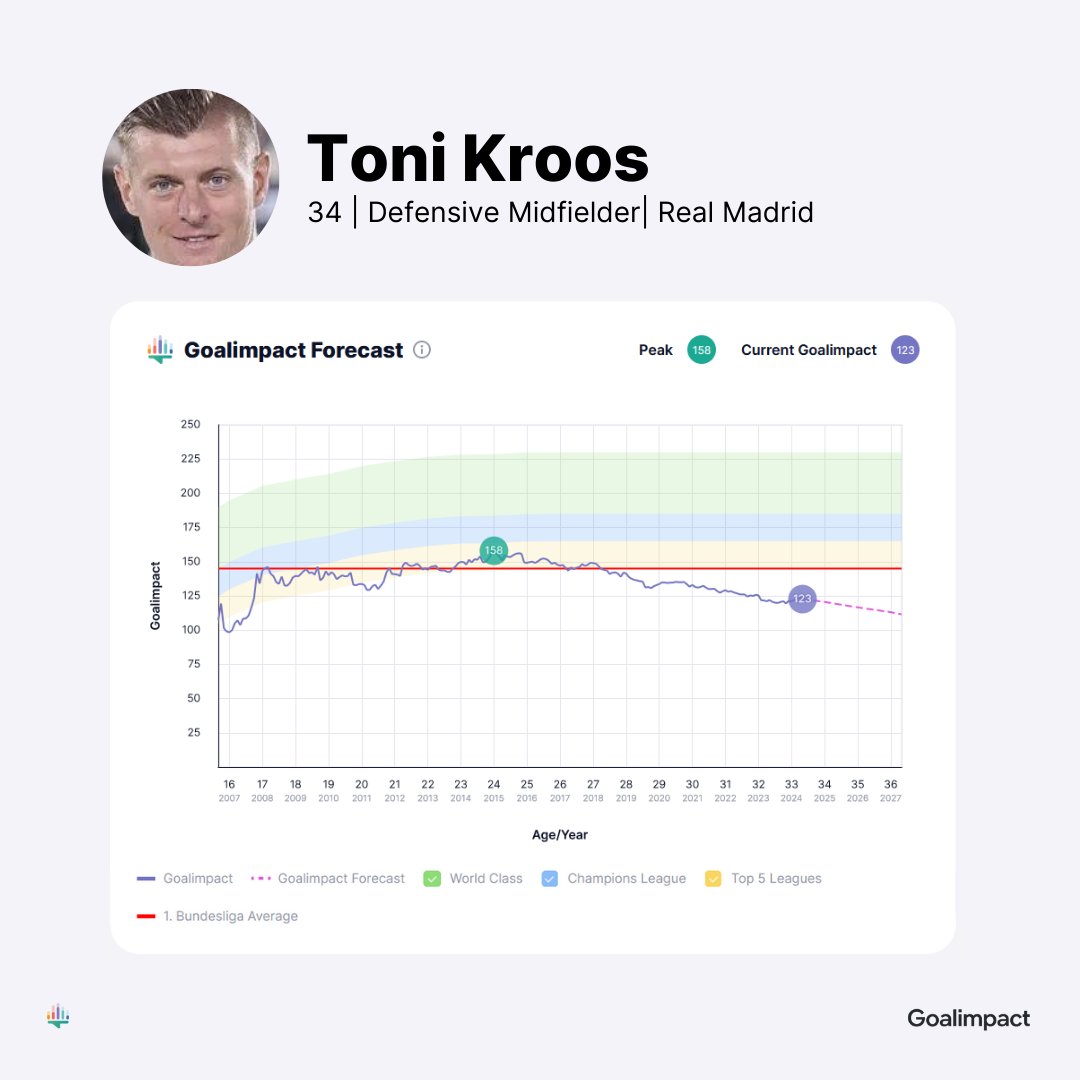

Not every top-down model is quite as high on Kroos. The data consultancy Goalimpact markets professional player ratings to European clubs and player representatives that are based on an adjusted plus-minus framework. Like Hvattum’s model, Goalimpact tries to isolate a player’s impact on his team’s bottom line while controlling for context, but even after their adjustments, Kroos’s numbers are “the big mystery,” according to Peter Mays, the company’s head of business development.

Back in his mid-twenties, when he played for Bayern Munich and won a World Cup with Germany, Kroos’s Goalimpact score was good enough to walk into most Bundesliga starting line-ups. “But when he changed to Real, things went downward,” May says. “Now, for us, he’s more on the level of a second-league player.”

It’s worth pointing out here that the debate about Kroos’s overall impact isn’t confined to data models.

“I like Kroos a lot. He put in some world-class performances and was great at Bayern, but his style of play is outdated,” former Bayern president Uli Hoeness said a few years ago. “It should be said that Kroos doesn’t fit in in the modern game with his horizontal passes. The game is now played vertically. Players take the ball and carry it forward with speed.”

The legendary German midfielder Lotthar Matthaus, on the other hand, has called Kroos “perhaps Germany’s greatest footballer”.

Football is tricky like that — even professional scouts watching the same games often disagree in their player assessments. The whole point of top-down player ratings is to take an algorithmic machete to the thicket of opinion and try to arrive at some kind of objective truth. But when even the models disagree, how do we know what to believe?

“When I see Kroos, I see a player who has fantastic passing technique, perhaps one of the best in the world, but there is more to the game,” Mays says. He speculates that Kroos could hurt his team defensively, for example. That side of football is hard to measure with on-ball stats but can show up in more holistic impact ratings.

“But I may be cherry-picking,” May admits. “I am aware that I could be biassed from Goalimpact to find the reason why Kroos is bad. So I’m a confirmation-bias victim right now.”

One way to assess player ratings is to check them against, well, other player ratings. Goalimpact has found that their score “correlates well with other indicators of player quality, such as market value, wages, and national team caps”. They also track player scores over time to measure how well the model predicts a player’s development.

Hvattum prefers to check his model by using it to predict match results, which he can test across years of data. “If I give you two different sets of player ratings; if one of them is better than the other, then they should be better at predicting the outcome,” he says. “For this type of model, it’s hard to say that the numbers lie.”

One practical drawback of top-down models is that it can take them years to get a good read on a player’s impact, which poses a challenge for clubs that want to use them for scouting. “Obviously, you want to be able to see how a player trends in a shorter period of time than like three-plus years, right?” says Edvin Tran Hoac, a data analyst for the Washington Spirit in the NWSL.

In a public model called contextualised plus-minus, Tran Hoac started with long-term top-down ratings, then used a bottom-up approach based on detailed on-ball stats to model players’ overall impact. That hybrid technique helped him get a faster read on players with fewer minutes, and he also found it could also help cut through the noise of plus-minus.

“Kroos’s long-term RAPM was always good — not as bad as his on-off numbers would say,” Tran Hoac says, referring to regularised adjusted plus-minus. When he modelled Kroos’s impact from bottom-up stats, however, “he was one of the top centre-mids in the world”.

So which one is the real Toni Kroos: the ageing midfielder whose spotty defending and overrated switches may be secretly hurting his team, or the gloriously press-resistant passer whose brilliance on the ball has won every team trophy there is to win — the all-time great who may have been, however briefly, even better than Lionel Messi?

“Maybe there is something he does that makes him a little less valuable than public opinion would suggest, but he surely is not as bad as his on-off numbers,” says Tran Hoac, laughing at his own cautious answer.

“Like a lot of things in data science, we don’t know everything. We’re trying.”

(Top photo: Jorge Guerrero/AFP via Getty Images)

Read the full article here