The Athletic has been attending some of the most ferocious derbies across Europe, charting the history of the continent’s most deep-rooted and volatile footballing rivalries.

The series began last season, covering 10 combustible fixtures from Athens to Anfield. We attended De Klassieker and the Derby della Capitale, the Eternal Derby and the Old Firm. We then resumed our journey this season by taking in games in Copenhagen, Salzburg, Lisbon and Belfast.

We were in Ipswich and Zagreb in December, then Sunderland and the Black Country, and watched Sparta play Slavia in Prague. Last month, we were in Poland for the Great Silesian derby.

Now we branch further afield with a trip to Mexico, and the derby which crowns the King of the North…

The scene is the Estadio BBVA in Monterrey, and the latest edition of the Clásico Regiomontano has fully devolved into madness.

The Clásico Regio, as the locals commonly call it, pits two neighbors against each other in a quest for regional dominance.

CF Monterrey and Tigres UANL are the city’s two sides and, in recent years, they have become powerhouses of Liga MX, the Mexican top flight.

Around here, Tigres is sometimes viewed as the team of the working class. Many view Los Rayados (the stripes) — the common nickname given to Monterrey due to their blue and white kit — as something entirely different, and the stadium we’re sitting in does a good enough job of painting that picture.

Nestled into a mountain valley, it is much flashier and glitzier, much more polished than Tigres’ home ground.

By the time the 100th minute approaches, everyone here feels like they have lived a lifetime. Recently, this derby has had a hard-earned reputation for not living up to the hype that surrounds it, but this has been an entirely different story. We’ve had five goals, a red card and several closely-contested calls. In the tunnel that leads to the field, Monty, Monterrey’s human-bulldog mascot, sits headless and drenched in sweat on a chair as an assistant hands him a Gatorade. He looks like he’s about to pass out.

Fans in the stands are fully soaked in perspiration and beer, and Monterrey’s ultras — their barra brava, as they are referred to in Latin America — are in full voice, ear-piercingly loud from clear across the stadium.

High above all of this, Tigres’s regular starting goalkeeper, Nahuel Guzmán, is sitting this game out with a knee injury. It has not stopped him from trying to impose his will on this game from his luxury suite. He has spent the game aiming a high-powered laser pointer — an implement of s**thousery normally reserved for the common fan — at Monterrey’s goalkeeper, in an attempt to blind him.

Deep into stoppage time, Monterrey is down 3-2. Rayados midfielder Sergio Canales steps up for what surely will be the final action of the game, a corner kick. He drives it across the area towards Argentinian forward Germán Berterame, who rises above the fray and powerfully heads home the equalizer.

Berterame celebrates his late equalizer (Fredy Lopez/Jam Media/Getty Images)

The ensuing moments are as chaotic as the game itself.

In the press box, journalists are sprayed with beer by fans, laptops and cell phones be damned. The local police — there are hundreds of them here — have started celebrating too, dropping the militaristic facade for a moment in exchange for a few wild embraces. Berterame chooses to celebrate his goal with Canales in the corner but, by the time he arrives, the Spanish midfielder has collapsed in exhaustion, ravaged by cramps.

In the following days, local media will tout this as possibly the greatest Clásico Regio ever played. Right now, it feels hard to argue with that.

Globally, Mexican football is defined by one principal rivalry — Club América versus Chivas de Guadalajara; El Clásico Nacional. That matchup is universally known as the premier derby in North America. It is rich with history and titles. Even today, the head-to-head between Mexico’s most well-supported clubs is viewed as a must-see contest with historical significance.

Liga MX titles, however, have been decided most recently between Monterrey and Tigres. Two neighbors in the Nuevo León region who, quite frankly, do not get along. Monterrey has become title town, much to the chagrin of clubs in the nation’s capital, Mexico City.

Since 2015, Tigres and Monterrey have won six titles, with Tigres claiming five league trophies in that span. Both clubs are now among the richest in Mexico, with squad valuations reaching upwards of €150million (£128m; $160m) between the two. Club América and Chivas are traditional powers, along with Mexico City-based Cruz Azul and Atlas of Guadalajara.

But the Clásico Regiomontano, which crowns the King of the North, is today’s most passionate Mexican derby; one that is rapidly gaining respect and cachet abroad.

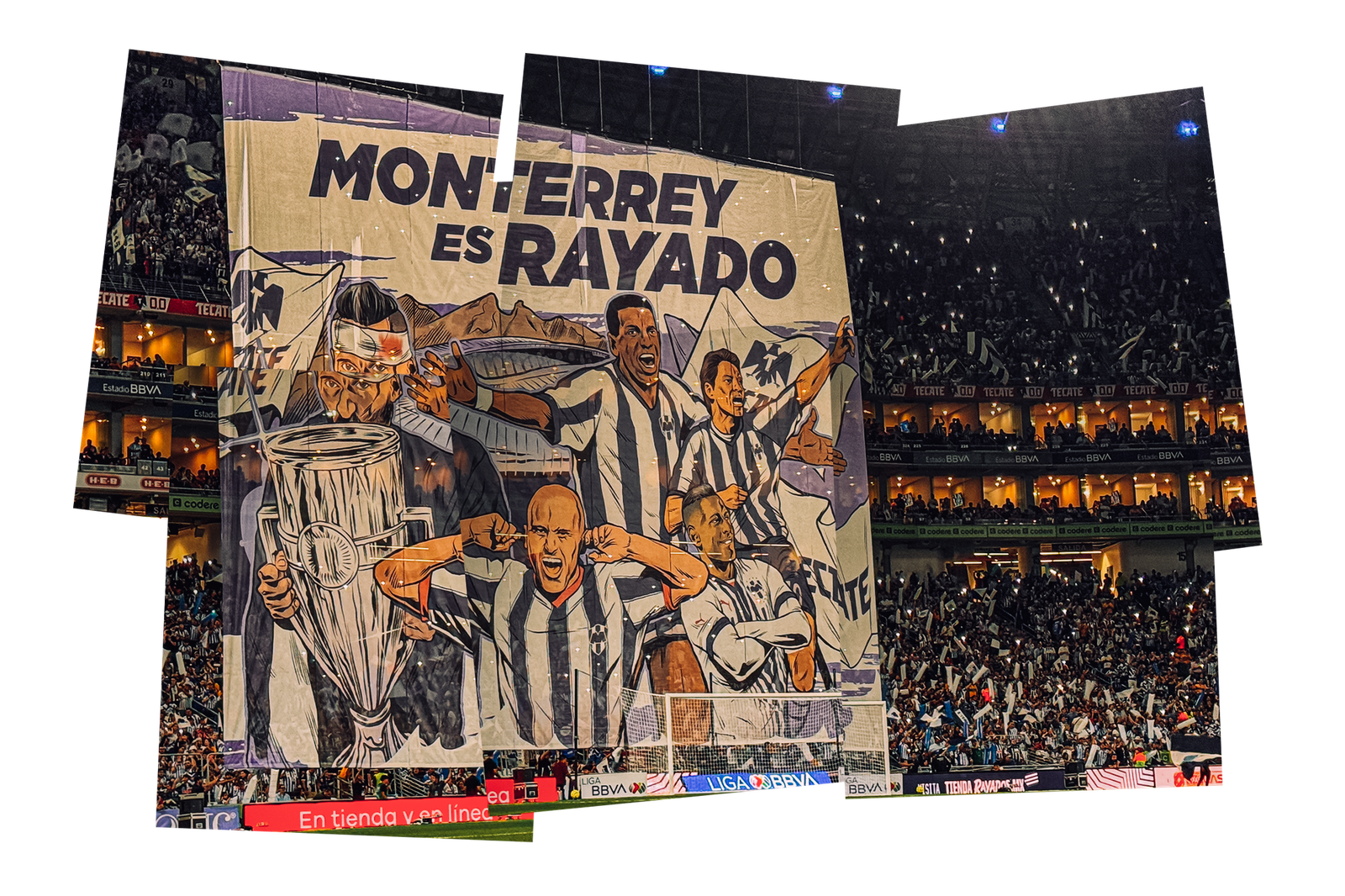

The Monterrey supporters’ tifo (Pablo Maurer/The Athletic)

It was not always this way, of course.

Monterrey (founded in 1945) and Tigres (1964) were minnows of the Mexican game for decades in a town where baseball was king. The two sides first met in a Regio in 1974, playing for little more than local pride. It took decades for the rivalry to develop into what it is today, with the Clásico largely defined by two crucial results.

In 1996, Monterrey met a lowly Tigres team that was just one loss away from being relegated. Los Rayados were all too happy to deliver that fatal blow, sending Tigres down to the second tier. The two sides met in the league finals for the first time 21 years later, with Tigres besting Monterrey in a tense, two-legged affair and claiming the 2017 Apertura title at the Estadio BBVA. The two have jostled for continental glory as well, with Monterrey defeating Tigres in the 2019 CONCACAF Champions Cup final.

That 1996 relegation was the genesis of Tigres’ ascension to the upper ranks of Mexican soccer. Cemex, the fifth-largest cement company in the world, purchased the club and the ownership began spending indiscriminately. Tigres won both split-season league titles the following year and were back in the first division almost immediately, where they’ve remained since. In 2020, Tigres made the finals of the Club World Cup, a first for a CONCACAF side.

Tigres’ Juan Brunetta celebrates with his team-mates (Pablo Maurer/The Athletic)

In a way, Monterrey followed a similar path.

Just three years after Cemex swooped in on Tigres, Los Rayados were purchased by FEMSA, the largest bottler of Coca-Cola in the world. They, too, embarked on their own quest for regional and national dominance and, for a stretch in the mid-2010s, entered a golden era of sorts, becoming the most dominant team in North America and a fearsome opponent in continental competition.

The differences between the two teams are readily apparent in their home grounds.

Tigres plays at Estadio Universitario, an ageing, concrete venue situated on the grounds of UANL, the largest university in the city. The club is affiliated with the university and sports its colors.

El Volcan, as the stadium is commonly referred to, feels more South American than Mexican, a relic of the days when football stadiums were used for football and little else. The suites in the place feel basic, the seating areas even more so. Earlier this week, during Tigres’ Champions Cup encounter with Major League Soccer side Columbus Crew, fans lined the railings of the upper deck two or three deep, leaning over to see things better.

Outside the stadium, a bit of a micro-economy had set up shop. Vendors hawked tacos and tortas and every other iteration of Mexican cuisine imaginable. Others sold bootleg jerseys, from Tigres to Rayados and even a few of Lionel Messi’s Inter Miami kits to boot. Yet others provided services more tailored towards the stadium’s unique location — “Se guarda mochillas” (“Backpacks stored here”) read one sign. Dozens of them had been checked in at that table by university students who had finished their classes for the day and headed straight to the game.

The stadium has been the subject of replacement talk for years. In 2016, the club proposed building a “floating” 80,000-seat venue that would bridge the Santa Catarina river. Those plans were scuttled for environmental reasons. The governor in these parts, Samuel García, happens to be a Tigres superfan and has recently promised a new stadium. For now, the club remains in their humble, but very charming, home.

Monterrey’s home ground is a sight to behold, maybe the most scenic footballing venue in all of North America.

El Gigante de Acero (Pablo Maurer/The Athletic)

The stadium is sheathed in aluminium, riveted over a steel and concrete substructure. It matches the aesthetic sensibilities, in many ways, of the brutalist and retro-futuristic structures from the 1960s that dot many Mexican cities. Built by architectural firm Populous — the same people that handled Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium, rebuilt Wembley and are now completing Fulham’s new Riverside Stand — the place cost a comparative pittance (some $200million) but feels polished in every way.

The locals have their own name for it: El Gigante de Acero. The steel giant.

Its most unique feature, by far, is the view of Cerro de la Silla afforded to fans seated in the north-west corner of the ground — the peaks of a nearby 6,000ft mountain range loom large through the oval-shaped opening in the stadium’s roof. The view is breathtaking. During stops in play, your eyes will almost always inevitably wander upwards.

In 2026, the World Cup will return to Monterrey for the first time since 1986, and Estadio BBVA will host four matches in the tournament.

The difference between both grounds is stark, and that is not something that’s lost on their respective fanbases.

“Tigres fans, it’s the team of the people,” one of the club’s supporters tells us in the build-up to the game. “Traditionally, it was the team of the industrial workers. Monterrey was the team of the upper class — people who were already comfortable. There were statistics in the 1980s and 1990s that showed that when Tigres lost, production in the factories around here went down.”

It’s a narrative that’s parroted throughout our visit to Monterrey: Tigres, the team of the people, while Monterrey’s faithful are (fairly or unfairly) painted out as fickle, fairweather fans. That narrative seems to come to life during Saturday night’s Clásico when thousands of Rayados supporters head for the exits before the final whistle.

They would end up missing a spectacle.

Monterrey and Tigres line up ahead of their 3-3 draw (Azael Rodriguez/Getty Images)

It’s Friday night at Nandas 78, a bar and performance venue in Barrio Antiguo, Monterrey’s historic district.

Monterrey itself was a tiny blip on the map until it industrialized in the late 19th and early 20th century and this is the closest thing the city has to a proper historic district, with its pastel-painted, 18th-century colonial structures. Tonight, the area is a madhouse.

Partygoers stagger out of bars and clubs and struggle to stay upright on cobblestoned streets. The smell of grilled meat and corn tortillas engulfs every corner, as street-food vendors provide the traditional taco meal to balance out a night of drinking.

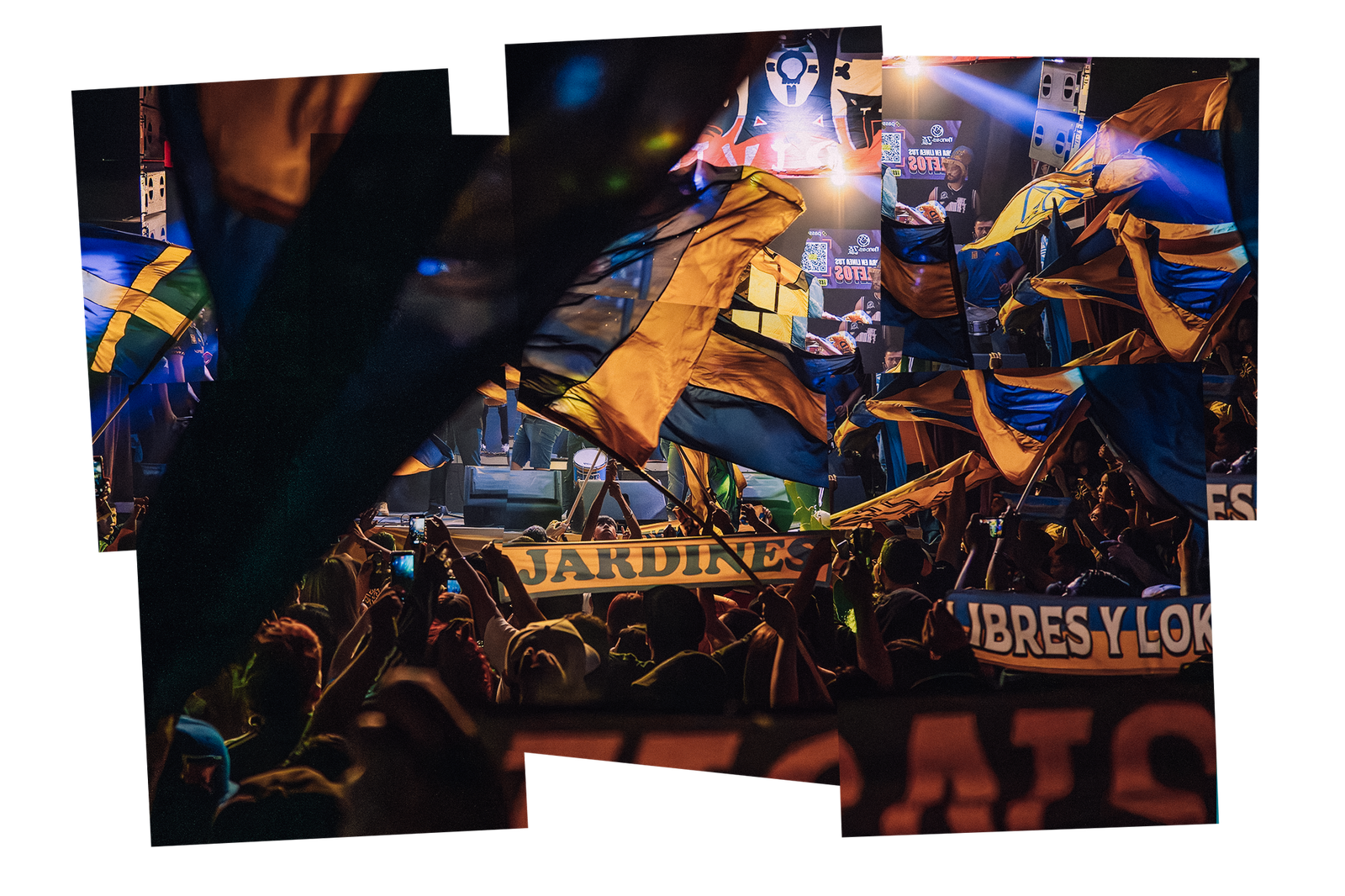

Friday night at Nandas (Pablo Maurer/The Athletic)

Tigres’ largest barra brava, Libres y Lokos, has gathered at Nandas for a pre-match party. It’s a wild scene: decked out in various iterations of the club’s iconic blue-and-yellow kits, hundreds of fans throw back 40oz Tecate beers while a series of local bands rip through a playlist of club anthems and Mexican tunes. The place is so full you can barely move, with revelers hanging off second-level balconies and crowding stairways.

It’s the type of party you might see in the stands on matchday. And that was sometimes the case in Mexico until the last couple of years, when Liga MX cracked down on fan violence.

In March of 2022, a massive stadium riot in Querétaro made global news, sullying the reputation of that club and the league as a whole. The league immediately banned Querétaro’s ultras from attending home matches for three years. Additionally, that group was not allowed to attend matches at other Liga MX stadiums for one year.

Those restrictions now apply to nearly every stadium in Mexico for all traveling ultras. Liga MX has instituted a fan ID system at every ground, a form of facial recognition that ensures nearly every fan is on the grid, so to speak. Fan violence at matches in Mexico still exists, but is a rarity.

“Tigres is everything to me — it’s my religion,” says Arturo, 31, a Tigres ultra, outside Nandas. “I’m not going to the game tomorrow because it’s dangerous for Tigres fans. It can get really heated.”

Back on the dance floor, the party is truly set off when La Murga De Tigres, the band that leads the Libres y Lokos inside the stadium itself, takes the stage. The audience becomes a sea of waving Tigres flags and beer spray as fans douse each other with alcohol. The first 10 rows or so in front of the stage devolve into a mosh pit and the entire audience belts out the club’s traditional chants, including one dedicated to their Rayado rivals.

“We were champions first, on your pitch, thank you for the joy of watching you cry… Dale (Go ahead) Tigres, dale Tigres!”

Not long after, a drummer dressed as The Joker from Batman joins the band on stage for their final song. About midway through it, he lifts his mask and reveals his true identity: it’s Tigres’ goalkeeper Nahuel Guzmán, the man who will trade a snare drum for a laser pointer the next night. He’s an eccentric club legend known globally for his theatrical take on the art of goalkeeping.

Tonight, he’s simply a fan.

Tigres’ Guzmán was injured but still the centre of attention (Hector Vivas/Getty Images)

Both Tigres and Rayados have burst onto the scene of late because of their high-priced squads.

Rayados in particular has become a regular source of talent for the Mexico national team. Five Monterrey players were included in the 26-man squad at the 2022 World Cup. Monterrey also established a new Liga MX transfer record last summer with the signing of Spain international Canales from Real Betis of La Liga.

Despite their humble origins and home stadium, Tigres have become Mexico’s glamor team.

The side regularly repatriates Mexican players from clubs in Europe, paying them handsomely to return to the country and play for titles. Tigres has also made an effort to recruit European footballers to raise the club’s profile. Some of these have failed to adapt to life in Mexico, namely France’s 2018 World Cup winner Florian Thauvin who, in 2021, appeared in less than 40 official matches before his contract was terminated.

The lone exception is another former France international, André-Pierre Gignac, who arrived at Tigres in 2015 from France’s Marseille. Today, Gignac is the club’s all-time leading goalscorer — a legend whose trophy-laden time at Tigres is nearing its inevitable conclusion. No Tigres player in the club’s history has scored more goals in the Clásico Regio than the French striker.

“The Clásico is very important to me,” Gignac tells ESPN Mexico days before Saturday’s clash, in perfect norteño Spanish, the dialect of Mexico’s northern region. “It’s not only about winning or drawing that match. It’s about making our supporters proud. We want them to leave the stadium knowing that we gave everything.”

André-Pierre Gignac (Pablo Maurer/The Athletic)

“Gignac has been the best player of this era,” says Samir, 47, a local taxi driver and die-hard Tigres supporter. A small photo of Samir’s wife is conveniently placed on his dashboard. In the photo, she’s wearing a Tigres kit.

“The Clásico is the biggest game of the year. Every player wants to feature in this game,” Samir says. “Gignac has always delivered for us.”

Samir’s excitement is evident as he describes what the derby means to Nuevo León.

“It’s bedlam,” he says. “On that day, the players’ injuries are suddenly all cured! The players know what it means to the city. I know a guy who traded in his car for a ticket to the final in 2017 between Tigres and Monterrey. Imagine that. He traded a $6,000 car for one match ticket.

“These people are very committed to the team. It’s beautiful.”

Monterrey’s Víctor Guzmán holds off Tigres’ Fernando Gorriarán (Pablo Maurer/The Athletic)

In the days leading up to the Clásico, we’ve heard much about the intensity of the rivalry and the hatred between both of these teams. We’ve heard about the socio-economic differences between the two fanbases and we’ve heard supporters from both sides of the spectrum talk about fearing for their safety at both stadiums they play in.

The gameday environment, though, was more amiable than expected.

Friends and family members wearing both sides’ kits entered the stadium together, something that would be unthinkable in some of the world’s other most intense rivalries. Children in both colors chased footballs along the concrete pathways and street vendors outside sold kits from both teams. The police looked bored. So did the horses they were mounted on.

A street vendor outside Monterrey’s Estadio BBVA (Pablo Maurer/The Athletic)

That’s not to say there isn’t gamesmanship, which is part of every derby. Tigres fans were especially confident heading into the 135th edition of the Clásico. Tigres won the previous meeting in September, 3-0.

“This is our second home. We won a final here,” says Julio, 31, a Tigres supporter. “We feel at home here. We feel safe coming here.”

On the upper deck of the stadium we find Jesús Arroyo, 42, as he exits the supporters’ section, an area that’s closely guarded by dozens of uniformed police. Arroyo has been a Rayados ultra since 2000. Alongside him is his wife Gabriela, 45, whose red hair pops among the sea of blue and white.

“The Clásico is very important to us, to Rayados,” Arroyo says. “It’s a must-win match every single time. Tigres owes us several. They’re the enemy. Both teams used to be down and now we’re always fighting for titles.”

Jesús Arroyo and his wife Gabriela (Felipe Cardenas/The Athletic)

Arroyo says that he named his eldest daughter Albiazul, a term in Spanish used to describe a color combination of blue and white. Gabriela chimes in authoritatively: “We have four daughters, and none of them wear yellow. That color isn’t allowed in our home.”

Many households in Monterrey are divided by the two clubs, though. As is common within city rivalries around the world, an uncle, a parent or a grandparent can influence club loyalties. At the Estadio BBVA, we see many couples in opposite colors walking together among the masses.

We stop Mario, 35, and his wife Claudia, 34, before they enter the stadium. For them, the Clásico Regio does not bring about any marital troubles.

“No, it’s always friendly and what happens in the game stays on the pitch,” Mario says, who is wearing a Monterrey shirt and cap. “We’re here as a family. The loser buys lunch, that’s it.”

“I’ve been Tigres my whole life,” says Claudia. “But I’m not as passionate about the derby as he is.”

Mario and Claudia have divided loyalties (Pablo Maurer/The Athletic)

There’s passion in this rivalry to be certain, but outside the stadium, it feels a little more sanitized and tempered than some of global football’s most heated ones. That is probably a good thing; Mexican soccer has seen its fair share of fan violence and it is an unquestionably positive development to move past that.

The scene in Monterrey feels distinctly friendlier these days and, at the stadium, more than one fan pushes back on the implication that there are even clearly-defined lines between both fanbases. Both teams are among Mexico’s elite now. It does feel a bit rich to associate Tigres, a team with a payroll which exceeds that of many European clubs, with Mexico’s working class.

“Todos somos de Nuevo León,” says Mario — We are all from Nuevo León.

The bigger argument, then, is about this rivalry’s place within Mexico and abroad. Unquestionably, Club América versus Chivas is still seen as the nation’s proper Clásico. But the longer Tigres and Monterrey continue to spend, and the longer they continue to outperform América, Chivas and the rest of the traditional Mexican powers, the more they’ll erode that belief.

Monterrey’s Fernando Ortíz hugs Tigres’ Robert Siboldi at the final whistle (Azael Rodriguez/Getty Images)

In the stadium’s media area after the match, Monterrey head coach Fernando Ortíz gives his thoughts on the rivalry. Before his coaching days, the Argentinian played for Boca Juniors and Estudiantes in his home country and briefly featured for Tigres. He also played for and coached Club América. This is a man who is not unfamiliar with North and South America’s biggest rivalries.

“Tonight proved that the derby has national significance,” Ortíz says. “It’s not just a regional derby. Both teams put on a show. It felt different. It can be compared to the Clásico Nacional.

“The city should rest assured that they have a derby that’s nationally and globally relevant.”

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here