The Athletic is attending some of the most ferocious derbies across Europe, charting the history of the continent’s most deep-rooted and volatile rivalries. The series began last season, covering 10 combustible fixtures from Athens to Anfield. We attended De Klassieker and the Derby della Capitale, the Eternal Derby and the Old Firm.

We resumed our journey with trips to Copenhagen, Salzburg, Lisbon and Belfast this season. We were in Ipswich and Zagreb in December, then in Sunderland for Newcastle’s visit and at West Bromwich Albion versus Wolverhampton Wanderers, both in the FA Cup.

Now to the Czech Republic and the fixture that divides Prague…

It is 2.30pm on a crisp, bright, early-spring Sunday and hundreds of Slavia Prague fans, all dressed in black, have started to gather in the city’s Old Town Square.

An hour later, ignoring the curious looks from puzzled tourists holding selfie sticks and with a police helicopter whirring above, they begin their short march over the Vltava River to the Letna stadium, home of their bitter rivals, Sparta Prague.

“When the fixtures come out at the start of the season,” Slavia fan Martin Benda says, “this is the one you always look out for.”

The Slavia fans are also wearing red and white woolly hats, each sporting the number ‘1892’ — the year their club was founded. Led by a supporter bellowing into a megaphone, they make their way up the steep flight of steps into Letna Park and on to the stadium, all to the thump of a drum.

The Slavia fans on their procession to the ground (Tribuna Sever)

Outside Gate F, where the away fans mass to be funnelled into their section of the ground, there is a huge police presence. The Slavia contingent eyeball their Sparta counterparts, a mess of provocative hand gestures and shouted abuse.

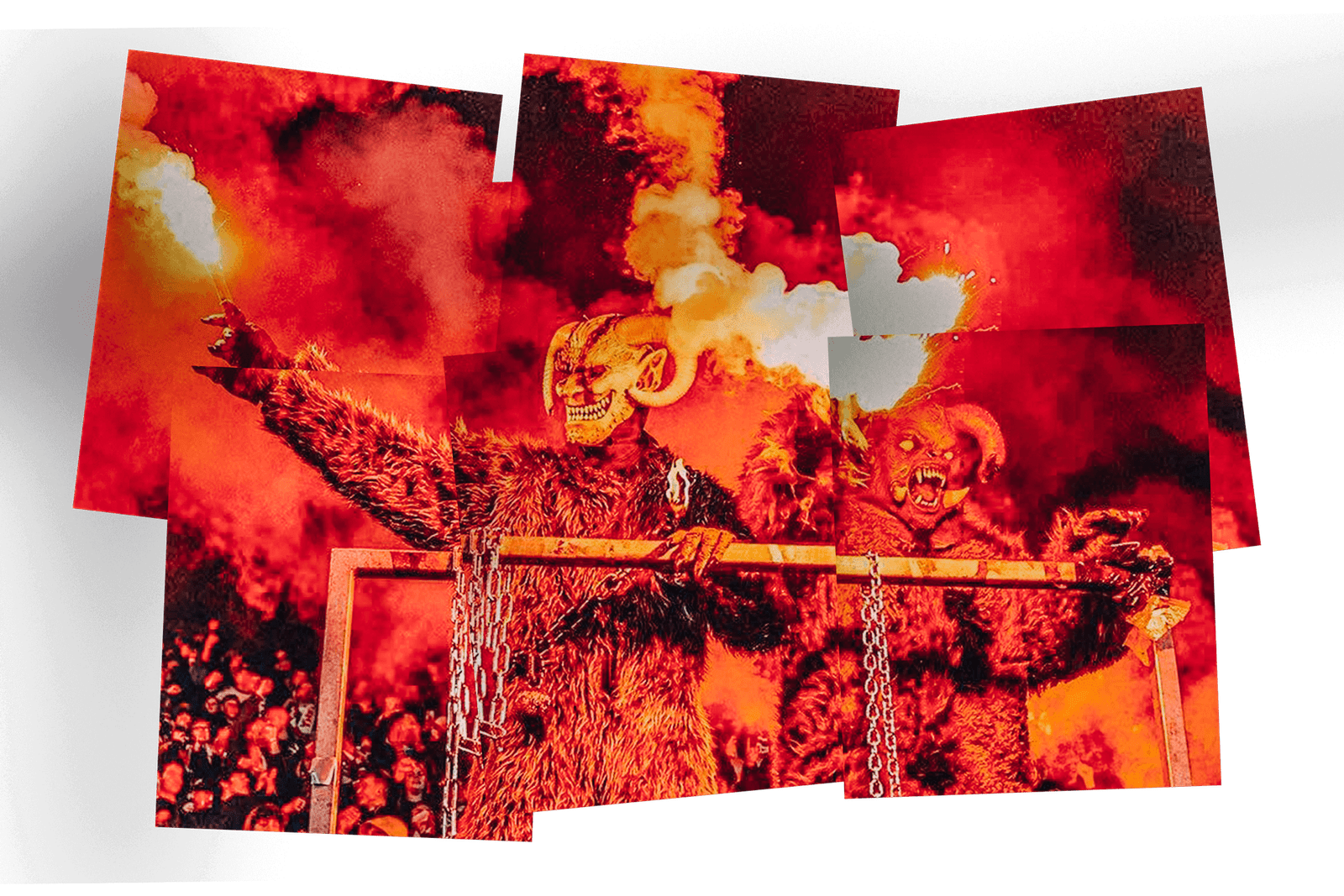

This is a city derby that needs no extra needle but, just to add more spice, it is also a massive game at the top of the Czech league; a do-or-die title decider. The two sides met just five days previously at Slavia’s Fortuna Arena in the quarter-finals of the Czech Cup, a game Sparta won 3-2, deep in extra time. As the teams came out for that match, Slavia’s fans created a ‘Welcome to hell’ tifo that ran across two stands of the stadium, with some supporters dressed as devils to complete the choreography.

With Slavia intent on swift revenge and desperate to drag themselves back into the title race, there is a real fizz in the air — and that’s even before the fireworks that erupt throughout the game.

Welcome to the 310th instalment of the Prague derby.

Welcome to hell, Sparta (Tribuna Sever)

This is a derby that has exploded back into life in recent years as Sparta and Slavia have reasserted their dominance at the summit of Czech football after periods spent drifting in the wilderness.

“The hype around the derby is the biggest it’s been in the last 20 years,” says Karel Tvaroh, who used to play for Sparta and now works in the media. “That’s mostly because both clubs are doing really well.”

A quick refresher: in the 16-team Czech First League, there are 30 games in the regular season — the top six then play a further five matches among each other as part of a championship play-off. The same format applies for the bottom six to decide relegation.

Sparta, the country’s most decorated club with 37 domestic titles, had a sticky patch in the 1970s, a decade where they even dropped into the Second Division for a time. They returned to their former glories in the 1980s and 1990s, almost reaching the final of the European Cup in 1992, its final pre-Champions League season. Sparta’s list of illustrious former players includes the likes of Tomas Rosicky, Pavel Nedved, Petr Cech and Karel Poborsky and their names are inked on the stadium walls alongside their trophy tallies.

Slavia failed to land a title between 1947 and 1996, a painful 49-year drought. That 1995-96 season was also when they reached the semi-final of the UEFA Cup — today’s Europa League. After finally being crowned champions, it was then another 12 years before they won it again. Yet, since 2016, Slavia can claim to have knocked their bitter rivals off their perch, winning four championships to Sparta’s one. They now have 21 in total.

But it is Sparta who currently hold the bragging rights in the city having triumphed last season, their first title in nine years. They went into Sunday’s meeting four points clear of their city rivals.

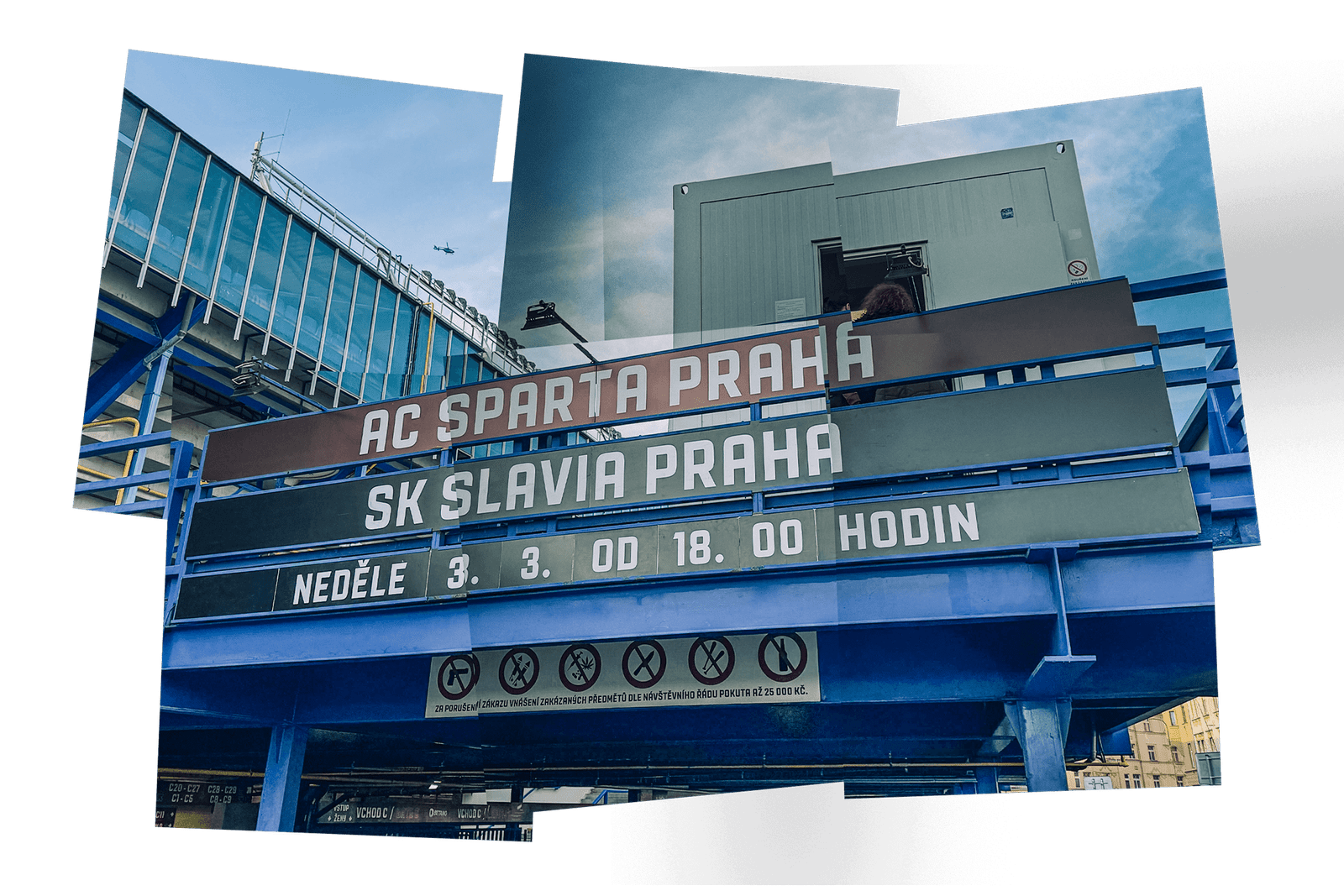

Stadion Letna gears up for the derby (Tom Burrows/The Athletic)

The first Prague derby took place in 1896. Historically, Sparta are said to be the club for the working classes, while Slavia were the team of choice for students and intellectuals — Vaclav Havel, the first Czech president, was one of their supporters; Edvard Benes, president of Czechoslovakia until 1948, played for their reserve team — however there is no obvious class distinction today.

They are separated by the waters of the Vltava, a river that runs through the city. Sparta are based in Letna on its west bank, with Slavia’s home in the Vrsovice district to the east. While this geographical split does not dictate who follows which club, fans still refer to their hated rivals as “the club from the other bank”.

This is a rivalry that’s not just confined to Prague, however, with huge numbers of fans across the Czech Republic’s 10 million population pledging allegiance to either Sparta or Slavia.

Sparta’s nickname of ‘Iron Sparta’ dates back to their dominant period after the First World War. The Velvet Revolution in 1989, a protest that ultimately led to the end of 41 years of Communist rule, began at Letna Park, just in front of Sparta’s ground.

Slavia were once based in Letna as well and even shared Sparta’s ground for a time after theirs was destroyed by shelling during the Second World War. Their new stadium was then bulldozed to make way for a giant statue of Joseph Stalin, the former leader of the Soviet Union, which meant they had to relocate to Eden. In 1953, under Communist rule, the club had to change the colour of their shirts from red to blue and were renamed ‘Dynamo’ for a period at that time, as Slavia was deemed the symbol of the intelligentsia and linked to the Republic of Czechoslovakia.

Since 2008, they have played at the Fortuna Arena, formerly Eden Arena, in a more residential part of the city, where they have enjoyed a golden period. This was the stadium where West Ham, a popular club in these parts because of their Czech (and ex-Slavia) players Tomas Soucek and Vladimir Coufal, won the Europa Conference League final last season and David Moyes danced to a naughty song about Jarrod Bowen.

Describing the rivalry, Michael Durc, a Sparta season-ticket holder, said: “With Slavia, it’s an intense but romantic rivalry. We hate each other on derby days but, away from that, we will go for a beer.”

That summary rings true on Sunday.

Yes, both sets of supporters are desperate to claim bragging rights in the city, but if there is menace in the lead-up to the game, on the Slavia march or during the match itself, it does not manifest itself in violence. There are no links to the criminal underworld here, like in some derbies that have already featured in this series. The careful choreography, an important part of Czech fan culture, is clearly aimed to intimidate, but this is an atmosphere to embrace.

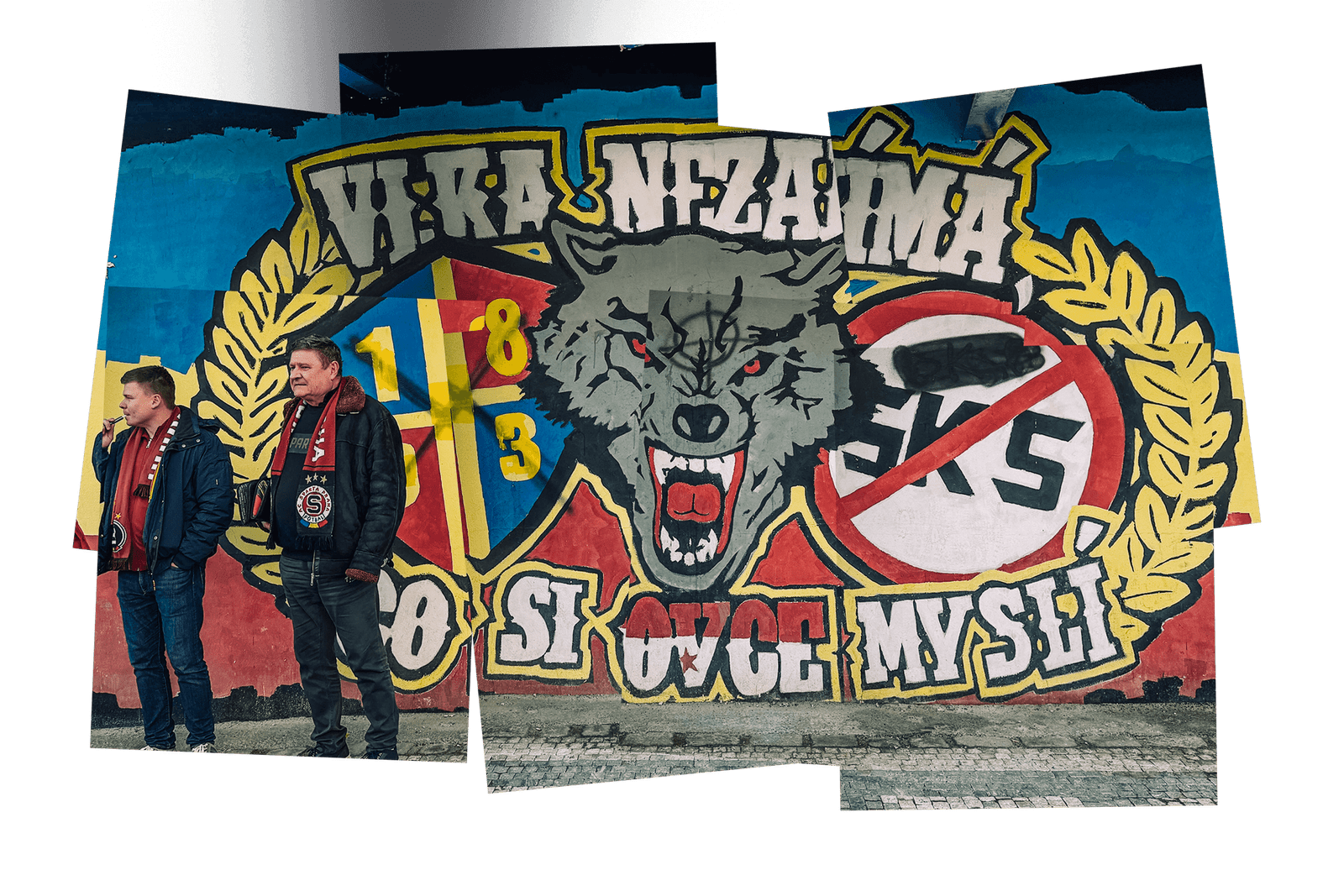

A Spartan wolf painted on a wall at Stadion Letna (Tom Burrows/The Athletic)

The Stadion Letna is a proper old-school arena.

Sparta fans mill around before kick-off sinking pints of Staropramen lager, the whiff of hotdogs heavy in the air. Underworld and The Prodigy blare out of the sound system inside the arena. As the two teams emerge and the noise ramps up, Sparta’s fans unfurl a banner depicting four famous figures from the club’s history — Vlasta Burian, Karel Pesek, Vaclav Jezek and Andrej Kvasnak. Each has given his name to one of the ground’s four stands.

After the thrilling cup game in midweek, the frantic start to the rematch hints at a repeat, yet Sunday’s top-of-the-table clash peters out into a forgettable goalless draw with plenty of sloppy mistakes from both sides. Slavia sit back deeper than usual, frustrating their hosts. Sparta, for once, can find no way to break their resistance.

The Burian, Pesek, Jezek and Kvasnak banner (Matyas Kohler)

Given the lack of action out on the pitch, the supporters find different ways to amuse themselves. Only 20 minutes in, Slavia’s away end, bouncing up and down together in unison, raise an enormous banner of a fan wearing sunglasses with an ‘1892’ hat on and create a flashing light display. The year 1892 is important to Slavia — crucially in their eyes, their club were founded one year before Sparta came along in 1893.

Then there are the flares and pyrotechnics. The fireworks explode at various points over the 90 minutes, momentarily halting proceedings more than once as the penalty boxes are enveloped in acrid smoke. They provide the game’s crackling entertainment.

A late red card for Sparta’s in-form Angelo Preciado does spark a rallying cry from the away section, but the visitors are not able to capitalise and pinch a famous away victory.

At the end of the cagey tactical battle that keeps Sparta four clear at the top, both teams soak up the applause from their supporters, who seem relatively content with the outcome. Sparta’s players huddle in the centre circle, provoking a last roar from the home end.

The away fans remind their hosts that Slavia were formed before Sparta (Tom Burrows/The Athletic)

Trading barbs with one another across the arena, it is clear the two Prague clubs are backed by passionate and raucous fanbases.

They can also both count on very wealthy owners.

Sparta are owned by Daniel Kretinsky, who boasts an estimated fortune of $10billion (£7.9bn at the current exchange rate), having bought the club with co-investors in 2004. Kretinsky, who made his money in the energy industry, has since branched out by investing in Sainsbury’s supermarkets, the UK’s Royal Mail postal service, the Foot Locker sportswear chain and French newspaper Le Monde. In 2021, he bought a 27 per cent stake in West Ham, which valued the London club at around £600m.

Kretinsky rarely gives interviews, earning himself the nickname of ‘The Czech Sphinx’.

He gets nervous before matches, and will always try to watch his team live when he’s in town. “When Sparta play, I’m paralysed,” he once said.

Perhaps not on Sunday night, mind.

In the 20 years since his group bought Sparta, it has not always been smooth sailing for Kretinsky. The club have gone through 22 different coaches and won just five championships. “For many years Sparta Prague were compared to Manchester United here, a sleeping giant,” says Tvaroh. “It was quite toxic and everyone was talking about the history.”

The nadir came in 2017 when Kretinsky hired Andrea Stramaccioni, an Italian who had previously managed Inter Milan. “That was the breaking point,” said Filip Horky, a Sparta fan and journalist.

Stramaccioni was heavily backed and allowed to bring in established, experienced players such as French midfield duo Jonathan Biabiany and Rio Mavuba. Even so, the team stuttered to a fifth-place finish in 2017-18. Stramaccioni lasted only 10 months at the helm — the fans quickly turned against him and even held aloft a banner depicting a plane ticket out of Prague.

Yet Sparta have since turned a corner. Their upward trajectory has been overseen by Brian Priske, a Dane who delivered that elusive title last season. He has been credited with creating a side with greater European flair, including the likes of Serbian winger Veljko Birmancevic, whose loan move from France’s Toulouse will be made permanent in the summer, and Finland international midfielder Kaan Kairinen.

Sparta supporters at a crammed Stadion Letna (Karolina Bartosova)

Martin Vait, a journalist from local news outlet Daily Sport, tells The Athletic: “I’ve never seen such a positive atmosphere around Sparta. Now we are seeing the best of Sparta — the grandiosity, the drama — and the stadium is rocking. When it’s rocking, the place is incredible. You saw that against Galatasaray (who were beaten 6-4 on aggregate in the Europa League last month to set up a two-leg round of 16 meeting with Liverpool over the next week). It’s like a proper, old-school English ground.”

“This is a high point for Sparta and football in the country,” season-ticket holder Durc adds. “The team is really good. (Sporting director and former Arsenal forward) Tomas Rosicky put together the team and the last piece of the puzzle was Priske — and the coach matters so much at Sparta. We can realistically eliminate Liverpool, especially as, for them, that competition isn’t a priority. It’s clicked because of Priske.”

But also because of Rosicky.

Sparta have moved away from a model of investing heavily in older players on long contracts — that too often created a dysfunctional dressing room — to put their faith in youth.

In an interview with The Athletic in January, Rosicky explained: “We changed the strategy completely. We tried to focus on the Spartans in the team, keeping that Czech core, because we’d lost our identity. We said, ‘We will need three years before we win again’. You can imagine, it’s not easy to say to people, ‘We won’t win now for three years’.

“We wanted to bring back the history, the identity, the never-give-up attitude, the Spartan identity: we want to play with intensity, we want to have the ball, we want to play from the back, we want to open the spaces.”

Gradually, that approach has paid off.

“I’m proud of what we’ve done,” Rosicky added. “It has not always been easy. After my third year, the people here turned against me. We lost the cup final, patience ran out, and the fans started chanting that I should leave. I went to the owner and the CEO and said, ‘If you think it’s for the best, I’ll finish — because I will not change the strategy. I think it’s correct’. But they stuck with it. They told me to find a new coach and continue.”

The home fans let off flares (Karolina Bartosova)

Slavia also have great riches at their disposal.

In December, Pavel Tykac, an energy investor, entrepreneur and the fourth-richest Czech with an estimated worth of $8.2billion, bought the club from Chinese investment group CITIC.

“I am among loyal Slavia fans, like my father and grandfather,” Tykac said at the time. “It is a big honour for me to share in Slavia’s further development.”

Standards were set by the previous ownership. Under CITIC, Slavia won three league titles and made three quarter-final appearances at continental level. They have impressed in Europe again this season, winning their Europa League group where they finished two points ahead of Roma, last season’s runners-up in the competition. They can also look forward to their own glamorous tie in the Europa League last 16 this week — against seven-time European champions AC Milan.

Jindrich Trpisovsky is Slavia’s tough-love manager. Appointed in December 2017, he demands total buy-in and strong fitness levels from the players so his high-intensity game will work. They ran Maurizio Sarri’s eventual tournament champions Chelsea close in a Europa League quarter-final in 2019 before losing 5-3 on aggregate. On Sunday night, Trpisovsky prowled the touchline in a bright white cap and matching trainers, taking satisfaction from his team’s resilience.

He has enjoyed tremendous success and taken the club to another level, but the high turnover of players has rather affected his magic touch. “Slavia were clearly the best team in the country for five years but now we can see that Sparta are stronger,” says Ondrej Kreml, a Slavia fan. “The new ownership is surely a reason for optimism — he is Czech, we bought some players in the winter transfer window — but it’s still early days to see what impact that will have.

“Even after all these years, Slavia fans still love Trpisovsky and can’t really imagine anyone else as manager.”

Sunday’s goalless derby was more eventful off the pitch than on it (Karolina Bartosova)

Driven by the progress made by Sparta and Slavia, the quality in the Czech league has improved markedly in the past decade and that has also boosted the game’s popularity. Stadiums sell out across the country. Broadcast revenues for the league are tripling next season.

But Czech football does still have issues to address.

On Sunday, Sparta fans chanted “Jude Slavia” at their rivals — an anti-Semitic slur with confusing origins. It is thought to date back to 1923 when Slavia were compensated for the costs of calling off a friendly against West Ham under an agreement with a Jewish-owned insurance firm. It can still be heard on the terraces today, despite appeals from Sparta officials and protests from Jewish leaders. In return, Slavia fans shout “Smrt Sparte” — Death to Sparta.

In the past, Sparta have been linked to far-right politics. In 2007, the club’s former captain Pavel Horvath was fined for giving a fascist salute in response to fans who appeared to be chanting “Sieg Heil”. Horvath insisted he had not intended the gesture, while supporters claimed they had been chanting “Siegl Heil” in reference to their former star player and then coach, Horst Siegl. During the 2015 European migrant crisis, Sparta fans held up a flag that read: ‘Stop Islam.’

However, there is a belief in the country that a shift has occurred in recent years, with the quiet majority taking on more of a voice instead of the vocal ultra-minority.

This was apparent in the pre-match build-up on Sunday when Slavia’s fans were escorted into the away end.

One sturdy and livid-looking Sparta supporter loudly started shouting “Jude Slavia” at them and encouraged others to follow his lead and join in.

Instead, he was met with a wall of silence.

Derby day in Prague (Matyas Kohler)

This particular Prague derby was far from a classic and failed to showcase the rise in quality in a league that is taking positive strides. In truth, both sides looked exhausted after their 120-minute marathon against each other in the cup on the previous Wednesday. Each also had an eye on this week’s exciting Europa League ties.

Yet it is a stalemate that kept the title race alive with 12 matches left to play. Despite the spectacle, as fans streamed out of the ground, there was a real sense of optimism and excitement at what is happening here.

For both Prague clubs, attention now turns to those bouts on the next two Thursdays against European heavyweights Liverpool and Milan.

One thing is for certain: this city will be rocking again.

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here