To reach Hamed Mamadou Traore’s home, you follow the Boulevard Francois Mitterrand out of Abidjan’s eastern outskirts, towards the district of Abata.

There are layers to the biggest city in Ivory Coast. The wealthiest areas are in Cocody and Riviera zones one and two, where families live in huge villas with vast gardens.

Abata is the next suburb along. It is dusty and lower middle-income but Traore’s house stands out because of its size and the security that surrounds it. It is more of a compound, protected by stone walls and a huge double-bolted steel door.

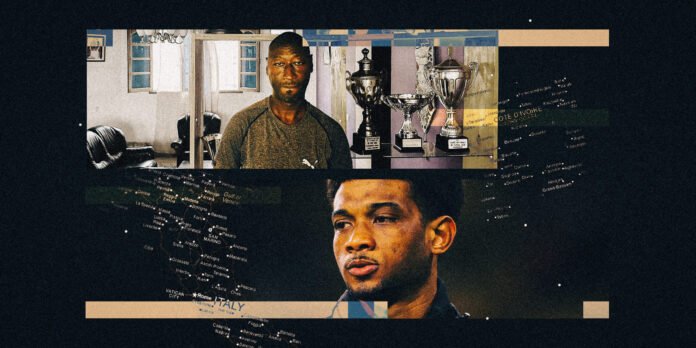

Traore meets The Athletic on the side of a nearby main road. He is dressed modestly, wearing a grey Puma T-shirt and shorts, with flip-flops. On the open-plan ground floor of his property, his brother is sitting at a kitchen table, with his feet up on a chair.

The fact that Traore is willing to speak at all is surprising. In the summer of 2020, he was at the centre of one of football’s most high-profile trafficking stories, having been accused by the Italian Football Federation (FIGC) of forging documents that enabled two players from Serie A, the top flight of Italian football, to have entered the country illegally.

They were Amad Diallo and Hamed Junior Traore. At the time of the FIGC hearing, Diallo was just emerging at Atalanta: less than a year later, his promise was recognised by Manchester United, who spent £37million to bring him to the Premier League.

Meanwhile, Junior Traore — who had claimed to be Diallo’s brother — had established himself in the midfields of Empoli and Sassuolo, before moving to England with Bournemouth in 2023. Last month, he returned to Italy after agreeing a loan deal with champions Napoli.

Hamed Junior Traore (right) is now with Napoli (Alessandro Sabattini/Getty Images)

According to Italian prosecutors, both of these players had been smuggled into the Reggio Emilia region of northern Italy by five adults. Hamed Mamadou Traore had acted as the father to both of these players, while his wife Marina Edwige Teher pretended to be their mother.

It was, prosecutors claimed, an elaborate operation, involving multiple family members. Teher’s sister and brother-in-law also claimed to be the parents of Diallo’s cousins, one of whom had secured a contract with Lecce, while another was representing a club in Serie D, the fourth tier of Italian football.

The family came to the attention of the Italian authorities during “Operation Baby Elephant”, the codename given to an investigation into the trafficking of footballers. In 2017, a series of arrests were made, including that of Giovanni Damiano Drago, a Parma-based agent.

Drago struck a plea bargain with police, which led to a suspended sentence of one year and 10 months in exchange for information about Traore.

Drago was accused of smuggling five players into Italy. Two of those had played for Leader Foot, the junior club in Abidjan run by Traore, whose home is just a few miles away from the Felix Houphouet-Boigny Stadium, one of the venues for this year’s Africa Cup of Nations, which concludes this weekend.

Having collected 14 caps between them, both Diallo and Junior Traore were included in pre-selection by Ivory Coast but neither made it into the final squad for the tournament.

Their cases are not unique in a continent which, according a 2013 estimate by the charity Foot Solidaire, might see 15,000 young men trafficked out of West Africa each year with the aim of pursuing a career in football. They have sometimes paid thousands of pounds to a middleman, only to get stranded in Europe, without the delivery of a promised trial or even accommodation.

In that context, Diallo and Junior Traore may seem like two of the ‘lucky’ ones — yet their cases also raise troubling questions, not least for the man accused of trafficking them.

As Traore arcs forward from a leather couch in his living room, it quickly becomes clear that he is angry with the conclusions of the Italian authorities’ investigation, and what was subsequently written about him.

Both his and his wife’s names appeared on the documents that, in 2015, enabled Diallo to register with Boca Barco, a junior club from the village of Bibbiano, and then Atalanta three years later.

Yet during questioning, when officers began to inquire into whether the players were even brothers, DNA samples confirmed that Traore and Teher were not their parents.

This led to a FIGC judgement in 2021 which said that the pair had “performed acts aimed at obtaining false or altered attestations or documents to evade the rules on entry into Italy.” The players were fined €48,000 (now £41,000 each; $52,000).

Now, three years later, Traore describes himself as the players’ “uncle”, insisting that Junior was named after him by his cousin when he was born. This, he insists, reflects how close he was to other members of his family.

As far as Traore is concerned, he was the players’ guardian when they entered Italy and he had the papers to prove it: he says he “adopted” both of them before leaving the Adjame area of Abidjan.

He also claims that he was not summoned to the hearing with the FIGC, telling The Athletic he “wanted to present my case”, although travel restrictions at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic would have made that difficult anyway.

Traore did not share the documentation relating to his ‘adoption’ of the two players with The Athletic when asked. He said he was following the advice of his lawyer, who is in possession of them so they remain in a “safe place”.

Adoption specialists have told The Athletic that while such documentation might hold weight in Ivory Coast, the challenge of securing legal status between foreign nationals subject to such arrangements when trying to get into Italy under any family reunification process would be a lot more difficult.

Traore says he originally went to Italy to learn to become a coach, having seen his own football career at Abidjan’s Stella Club ended by a serious injury. After creating Leader Foot in 2006, one of the club’s earliest success stories was Eric Bailly, who was born in Bingerville, close to Abata.

In 2011, Bailly was brought into the youth system at Espanyol in Spain after being spotted playing in a youth tournament held in Burkina Faso. In 2016, like Diallo five years later, Bailly joined Manchester United for a fee of more than €30million (now £26m; $32m).

Eric Bailly started at the same Abidjan club as Amad Diallo (Mike Owen/Getty Images)

Despite openings for some of his players, there were enormous challenges getting more of them into Europe at an age that would prepare them adequately for a new level of football.

In Traore’s mind, the only way to give talented Ivorian players a future of any kind was to create a pathway to a country with better education standards, sporting facilities and networks.

When he and Teher achieved legal status in Italy, he says he bought property in Parma with the help of a London-based investor. It was his conclusion that Diallo, in particular, was ready to move abroad because he was smart, not because of his talent with a football. Traore says Diallo was so skinny when he left Abidjan that imagining his development as a professional was “silly”.

He speaks of the “best conditions and support” that Diallo and Junior Traore received under his care. Each boy, he says, went to school until they were almost 18. They had their own bedroom and leisure time, developing their own circles of friends.

He suggests he treated the children as if they were “my own” and strongly denies any accusation of trafficking. “It is not very kind; it is not fair, this kind of feeling,” he says. “I am not a trafficker.”

When prosecutors in Italy spoke about the case in 2021, they loosely tried to explain what had happened.

“It wasn’t exactly human trafficking as they (the footballers) were aware of it and had a reasonable life with their fake parents,” an investigator said, before suggesting the players had not obviously been “disadvantaged” by their new life in Italy.

It was unclear, however, who had benefited from any newfound wealth. “We don’t know how much the families took and if any money went back to their real families in Ivory Coast,” the investigator admitted.

Traore, now 49, admits that he stood to benefit financially from Diallo’s progression yet he is adamant he was never out just to make money.

“I know that I have done something for my country,” he says, suggesting that proceeds from Diallo’s development would have been used for Leader Foot, which currently does not have access to a grass pitch, or many of the other basic amenities that players at clubs in other parts of the world take for granted.

Instead, when Diallo officially signed for United, six months after charges were brought against him by the FIGC, the name of the intermediary on his registration documents with the English Football Association was not Traore’s.

Diallo, now 21, has since moved on to another group called AMS Consulting but in October 2020, Sport Agency Futura, which is based in Italy, announced that it had secured the right to represent Diallo. “A big player in a big club,” they posted on Instagram. “Welcome Amad Diallo.”

The player liked the post. In July 2020, he had changed his name. Before all of this, he was known as Amad Diallo Traore but he dropped Traore from his name on his 18th birthday. From the following September, he was known legally as Amad Diallo.

Traore insists his relationship with the player remains as healthy as ever. He says he can understand why Diallo had to change his name, because he needed to create distance from himself and a negative story that was harming his reputation.

“Amad must continue to grow, that’s the most important thing,” says Traore, who claims he has an invitation to spend some time with the player in Manchester.

His experiences have made him wary of Europe, however. In his version of events, life became a lot more difficult when suddenly, nearly every major club in Italy wanted to sign Diallo. The fact that he could only choose one meant he risked upsetting a lot of people.

Hamed Mamadou Traore at his home in Abidjan (Simon Hughes)

While Atalanta gave his wife employment, Traore also wonders whether this could have all turned out differently had the player shown more appetite to play for Italy rather than Ivory Coast.

Traore says he has wanted to tell his side of the story for some time but he has been unable to because of the impact it might have on Diallo. He says much of the media, especially in Italy, is unsympathetic towards the difficulties facing African footballers.

“Many players choose a boat and arrive in Europe in a bad condition,” he says. “Look at Amad, there is a big difference. He went to Italy, where he had a good school education. He ate good food and trained all of the time. He was taken care of. We tried to help a kid who dreamed of earning a living.”

Behind Traore at his house is a cabinet of trophies. One is from the Dream Cup held in Toulon in 2016, which Diallo helped Boca Barco to win. On WhatsApp, Traore’s picture includes figures from his old club, Stella. He is standing beside Franck Kessie, the former AC Milan and Barcelona midfielder, now with Al Ahli in Saudi Arabia.

He says he “does not want to hear about Italy any more,” but it appears he is still trusted in Ivory Coast. The head coach at another junior club in Abidjan insists Traore is a “good guy” who just wants the best for his players.

“The experience, I can say it disturbed me and that made me sorry,” he admits. “But I was more worried about the kids.”

Traore and Diallo (Photo courtesy of Hamed Mamadou Traore)

Diallo’s United career so far has amounted to just 10 first-team appearances. There have also been loan spells of varying success, in Scotland with Rangers (three goals in 13 games), and last season in the Championship with Sunderland where 14 goals in 42 games helped the team push into the promotion play-offs.

The Athletic has invited Diallo to comment through the agency that now represents him. He has never spoken publicly about his childhood and the claims that he was trafficked into Italy.

What cannot be disputed is that Diallo and Junior Traore, whose representatives were also contacted by The Athletic, were trying to find a way out of Adjame, a vast impoverished district just to the north of Plateau, Abidjan’s business centre.

If Plateau is Midtown, imagine Adjame to be old Harlem, or the Bronx. It is not the poorest part of Abidjan but it is one of the most populated and it leaves you with a sense of needing to fight if you want to create space for yourself to breathe.

The area is famous for its market, one of the biggest in Africa, which opens at 4.30am every day and spills out from a three-tiered terrace and onto a busy street. It is estimated that one million people a day use it, with traders coming from as far away as Burkina Faso and Mali to buy and sell. It helps that a nearby train station has a line that leads all the way to Ouagadougou, more than 1,000km away.

If you have a stall at Adjame market, there is a level of prestige. When The Athletic visited on a Saturday morning, the intensity was off the scale. In the food hall on the bottom floor, salted fish dry in the sun, while nearby enormous snails with shells the size of small tortoises wriggle and slither. You can get anything you want here, including the bushmeat of wild animals like baboon, antelope and owl, which is banned for public food consumption in Ivory Coast due to threats of Ebola. Women carry hacked slabs of the stuff around on trays.

Traders at Adjame market (Simon Hughes)

You can make money in Adjame but for most people, hawking is the only way. Hamed Mamadou Traore was born here in 1975, while Junior came along in 2000 and Amad Diallo two years after that. Families tend to be huge and there is a culture of loose connections being described in definitive terms, particularly uncles or cousins.

Traore says the struggle in Adjame is real, but it breeds determination. “It’s training for life,” he suggests.

He identified Diallo’s football potential at a training session organised by his school during the holiday season. Having established Leader Foot, he was asked to coach some of the youngest players. Diallo was eight or nine and it was Traore’s judgement that he was already more intelligent and talented than many of the players who were older than him at the club.

Diallo joined Leader Foot, where Traore says he remained until he was 14. From the age of 12, however, Traore was trying to get him out of Adjame. Though the authorities in Italy fined him, they also conceded he was too young to have a say in the direction of his life. Perhaps only the player’s real parents know what agreement was made around this time but The Athletic has been unable to make contact with them.

An agent, who would like to remain anonymous to protect his working relationships, has encountered traffickers regularly in West Africa, though he has rarely operated in Ivory Coast. “It is more of a problem in Ghana and Nigeria,” he suggests.

It is “fairly widespread”, says the agent, for teenage footballers in the region to have a manager rather than an official representative. “It tends to be someone local who will take care of them financially.” This involves cash for new boots and food — “the sort of support you need to pursue a career”.

In many cases, the managers act as guides. Some, but not all, exploit the players. He says age cheating is common, and often aided by clubs because they benefit financially from moving on a player who isn’t quite as developed physically as he seems.

While the player is disadvantaged in almost every way when this happens because he finds it difficult to compete due to a lack of genuine maturity, the manager has the player under the thumb because he knows his dark secret.

There is no evidence that a process like this happened with Traore, Junior and Diallo in Adjame or Reggio Emilia.

The majority of players involved in trafficking cases, however, do not make it as far. According to Ed Hawkins, whose 2015 book The Lost Boys shed new light on the scale of the trafficking industry, such paths are more likely to lead instead towards criminality, with aspiring footballers lured in by drug gangs, prostitution or slave labour.

In Ghana, Hawkins had met a man called Tino, who was a kids’ football coach, hoping to deliver the next Michael Essien. He told Hawkins that if he found one, he would be able to approach the boy’s family and agree to adopt him for a small fee.

“This is normal in the footballing hotbed of west Africa where families see football stardom as their only way out of poverty,” Hawkins concluded.

Yet amidst charges and fines, silence and accusations, and the conflict of claim and counterclaim, the absolute truth behind what motivated Diallo’s journey to Italy, and why, remains shrouded in doubt.

(Top photos: Simon Hughes and Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

Read the full article here